The second act of Richard II (LCM, 1595) opens with the dying John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster asking Edmund, Duke of York for access to their nephew, the young monarch. He hopes to offer him ‘wholsome counsell’, but York warns that the king’s ear is ‘stopt with other flatt’ring sounds’. As he pleads his case for royal access, Lancaster draws upon a widespread early modern view of musical response:

Music’s power to compel attention is critical to his simile, which suggests that words can command similar attention when they may be the speaker’s last.1 Perhaps the idea of ‘deepe harmony’ implies a distinction between ‘deepe’ music that can ‘inforce attention’ and other music that presumably cannot. Above all, however, Lancaster’s rhetoric depends upon York agreeing that music (and dying words) can ‘[i]nforce’ the ‘attention’ of a listener. John of Gaunt’s choice of simile is unsurprising, for enforcement, or compulsion, was the most commonly invoked response to music in early modern England. When Richard II languishes in prison at the conclusion of the same play, and hears a rather inexpert performance from a nearby room, his impassioned complaint that ‘[t]his Musicke mads me’ is not just a marker of someone sensitive to badly played music, but also indicative of a wider culture in which one could not help but listen when it sounded (TLN 2727; 5.5.61). Likewise, Feste chooses to sing ‘Hey, Robin’ to another imprisoned listener in Twelfth Night (LCM, 1601) not simply to identify himself but to grasp Malvolio’s attention utterly, the gulled steward calling to the ‘Foole’ three times in quick succession upon hearing his song (TLN 2057–64; 4.2.73–80). For modern listeners, an out of time performance and snatches of a familiar song would probably have little in common with Orpheus’s ‘Iuory Lute’ that could ‘[c]harme Buls, Beares, and men more sauage to be mute’, yet as King Richard and Malvolio demonstrate in their reactions, even imperfect sounds were once expected to ‘inchaunt the hearers’.2 When music played in early modern England, it seems that people listened.

As the most common early modern model of musical response, enforcement must be central to our understanding of when and why music was used in the playhouse. This chapter explores how musical compulsion was articulated, and where the idea circulated, before examining how it translated into dramatic practice and playgoer response. It will ask how musical compulsion was understood in texts such as plays, travel writing, religious publications, children’s textbooks, news of contemporary events and printed music book paratexts. Such material allows us to trace the specific forms in which musical enforcement became familiar to a range of early modern subjects, this chapter’s primary evidence placing compulsion at the centre of popular understandings of music. After pursuing musical enforcement in the textual record, the chapter considers how the response informed uses of music at the Globe, in plays such as The Revenger’s Tragedy (KM, 1606), The Winter’s Tale (KM, 1609) and A Game at Chess (KM, 1624). The evidence suggests that pleasurable musical compulsion was a concept familiar to playwrights, actors, musicians and playgoers alike, profoundly shaping early modern musical dramaturgy. We can begin our investigation by tracing one term of musical enforcement that takes primacy over all others in the textual record.

Tracing Musical Compulsion

The paratexts of printed music books are strikingly suggestive of widespread ideas, assumptions and beliefs concerning music. A full examination of these sources reveals consistent, repeated uses of particular terms of musical compulsion, which under close scrutiny bear specific significations that no longer obtain in late modern usage. These paratexts are extremely clear about how best to describe the experience of music: the term ‘delight’ is used in its various forms (delight; delightful; delighting) in relation to music at least forty-five times in the paratexts of one hundred and fifty-nine musical works of the period, substantially more than any comparable word or phrase. For early modern writers, the experience of music is delight, and the two words are paired constantly both in these paratexts and elsewhere.3 This was a linguistic commonplace so familiar to early modern subjects that any reference to one must surely have evoked its connections with the other.

However, simply tracing the association of delight with music tells us very little about early modern musical compulsion. Whilst the connection is amply preserved in the textual record, the response that musical delight actually describes is by no means self-evident to a modern reader. Nonetheless, careful consideration of exactly how and when the term is used in early modern writings allows us to recover what it meant to early seventeenth-century subjects. To twenty-first century ears, ‘delight’ indicates extreme gratification: ‘To give great pleasure or enjoyment to; to please highly’ (OED, ‘delight, v. 1.a’). This was not the full story in early modern England, though, and a clue towards its earlier sense appears in its etymology, the OED citing the Latin verbs ‘delectare’, meaning ‘to allure, attract, delight, charm, or please’, and ‘delicere’, meaning ‘to entice away or allure’ (my emphasis). These italicized senses underlie an early modern delight not just pleasurable but also irresistible to the delighted subject. Music book paratexts confirm the term’s close association with compulsive experiences. A dedicatory poem to Thomas Greaves’s Songs of Sundry Kinds (1604) claims that his music ‘[d]elightes the sences, captiuates the braines’, and ‘is a charme against despight’, aligning charm and captivation with delight as descriptors of music’s affective power.4 ‘Charm’ and ‘captivate’ are both acknowledged early modern terms of musical enforcement: Linda Phyllis Austern traces them in some detail alongside the mythical ‘Siren’ model of engagement with female musical performance, for instance.5 Likewise, this 1604 paratext foregrounds the compulsive element of musical delight by pairing the senses’ delight with the brain’s captivation.

‘Delight’ also denotes attention seizing when paratexts tell their readers that a volume of music will ‘delight thee with varietie’.6 This popular phrase presupposes the reader’s full awareness of the mixture of attention seizing and pleasure that ‘delight’ denotes, upon which the claim of delighting ‘with varietie’ depends. Variety was a widely valued quality in early modern music and literature, and Thomas Morley offers a memorable account of how and why to offer it in his Plain and Easy Introduction to Practical Music (1597):

you must in your musicke be wauering like the wind, sometime wanton, somtime drooping, […] and shew the verie vttermost or [sic] your varietie, and the more varietie you shew the better shal you please.7

To complete the picture of delight’s distinctive early modern signification, we can trace its rhetorical conjunction with another term of musical compulsion. Here, rather than joining the charms and enchantments of harmony, delight is linked to the forceful, more threatening compulsion of ravishment, another common descriptor of musical experience in paratexts and elsewhere. Accordingly, Jacques Gohory, in a preface translated into English in 1574, pauses to ‘protest vnto you that if the songes of other Musitians do delight mee, those of Orland do rauish me’.8 As we shall see, ‘ravish’ is another significant term for musical compulsion, and Gohory’s construction here is illuminating. In showing how certain songs outstrip all others, he indicates that ‘to ravish’ is a yet stronger form of ‘to delight’. His comparison completes our reconstruction of early modern musical delight as a compulsive, pleasurable experience central to successful musical response, these paratextual moments offering glimpses of how delight was understood, particularly in relation to musical experience, in early modern England. This in turn allows us to make sense of the utter prevalence of the term as a description of musical response, and to re-read texts with an understanding that approximates a little better to that of early readers. It is in accordance with the preference of the sources, then, that ‘delight’ is taken up in this chapter to describe the compulsive musical experience that held such sway in early modern English thought.

‘Ravish’ was itself a widespread and familiar term for musical enforcement, though not quite as popular as ‘delight’: as Christopher Marsh notes, ‘[m]any music-lovers felt ravished in this period’. Even the king himself experienced the phenomenon, according to the printed account of James I’s journey from Edinburgh to London in 1603, for at the Earl of Shrewsbury’s house in Worksop, Nottinghamshire, an afternoon’s hunting was apparently followed by ‘most excellent soule-rauishing musique, wherewith his Highness was not a little delighted’.9 Once again, we can better understand musical compulsion through an excavation of how the term was used. Today, ‘ravish’ and ‘rape’ signify a different set of relations amongst a group of related ideas than they did four centuries ago, when the idea of unlawfully seizing someone’s property was often a primary sense, rather than sexual assault as we would expect today (OED, ‘ravish, v. 1.a’; ‘ravish, v. 1.b.i’; ‘rape, v.2 2.a’). The violation was both the taking of a woman seen as a possession of her husband, family or wider community, and the abuse that she would suffer.10 Thomas Heywood makes repeated use of the former sense in his Classical plays, in which Hesione is ‘rapt hence to Greece’, and ‘Pluto hath rap’t hence’ Proserpine. The same idea is explicit in William Corkine’s claim that his patrons Ursula Stapleton and Elizabeth Cope ‘are ledde away with a more then ordinarie delight’ in music.11 Musical ravishment involves being carried away by harmony, a notion also encompassed by ‘charm’, ‘allure’ and ‘delight’. Together, this cluster of terms suggests that music seizes and possesses a subject’s attention, regardless of whether they wish to be so affected. Significantly, writers of the period – even when not concerned with praising music or selling a volume of compositions – repeatedly seek to appear both convinced and convincing that musical ravishment of this kind is a genuine, everyday response to music.

Of course, the concept of musical ravishment remained strongly dependent upon the sexual sense of ravish, in conjunction with the idea of being ‘stolen away’. In a Restoration context, argues Marsh, ‘the words of Samuel Pepys reveal there was only a thin line separating the soulful from the sexual’.12 In pre-1642 usage, however, it seems that musical ravishment does not make a primary association between sexual and musical pleasure, but rather draws an analogy between the physiological processes of hearing and sex. Early modern sense theory understood hearing as a physical penetration of the ear: sound was not a wave, but a substantial species. As Penelope Gouk observes, ‘[t]he Aristotelian idea [is] that sound was produced by the striking of two bodies one against the other, carried through a medium to the ear’, and ‘the species of sound […is…] the concrete image thrown off by the sounding body’. Within the ear, this aural species then struck the spiritus, which ‘was the instrument of the incorporeal, rational soul’. As the species and spiritus mingled, the latter ‘immediately perceived whether it was pleasurable or painful’, in an extremely physical process.13 This provides a metaphor of hearing as male-female penetration recurrent across descriptions of compulsive musical experience, concurrent with and complementary to the seizing and leading away of musical ravishment. Many writers exploited this penetrative association, including Edward Sharpham in Cupid’s Whirligig (CKR, 1607), where Peg complains that a ‘voyce doth pierce the eare’ (K1v; 5.3.76–77).14 The ear is even bypassed by Baldassarre Castiglioni in one graphic metaphor: in Thomas Hoby’s influential translation of Il Cortegiano, he instructs readers that ‘many thynges are taken in hande to please women withal, whose tender and soft breastes are soone perced with melody and fylled with swetenesse’.15

Why did this sexual sense of ravishment strike so many writers as an apt figure for musical experience? Like the related notion of seizing and leading away, it seems to be a metaphor in part for the difficulty of resisting music. Unlike visual stimuli that might be shut out with eyelids, it is relatively hard to prevent sound entering the ear. And, of course, early modern witnesses are often clear that music makes particularly irresistible demands for attention. For twenty-first-century readers this is an uncomfortable metaphor, yet the analogy between hearing and ravishment was a central means through which seventeenth-century listeners comprehended musical sound. Indeed, the penetrability and, often, defencelessness of the ear seems to have appealed greatly to the early modern imagination even away from music, and Shakespeare’s Old Hamlet and Ben Jonson’s Morose present versions of this vulnerability as contrasting as their respective progenitors.16 Perhaps the primary reason why early modern writers found the term apt, however, is that the idea of the ear as passive receptor of sound species – contrasting with far more dynamic contemporaneous theories of visual perception – meant that the metaphor of musical ravishment united the experience of seized attention with the physiological process that was believed to cause this very response.17

One final example of musical ravishment completes this initial examination of the term. In his 1611 account of continental travel, Thomas Coryate describes a musical performance, ‘both vocall and instrumentall’, that was ‘so good, so delectable, so rare, so admirable, so superexcellent, that it did euen rauish and stupefie all those strangers that neuer heard the like’; indeed, this music was so powerful that he ‘was for the time euen rapt vp with Saint Paul into the third heauen’.18 Whilst the sense of being physically moved and taken to another place – the third heaven – depends upon one kind of ravishment, the use of ‘rauish’ alongside ‘stupefie’ also suggests the idea of being physically struck – and then ‘struck dumb’ – by the music, in a physiological process of hearing that resembles bodily ravishment. Coryate’s raptures demonstrate that the penetrative and kidnapping senses co-existed in seventeenth-century usage, and it is fortunate that he separates the two ideas, for it makes clear that both were at work when early modern subjects were ravished by music.

Having excavated ‘delight’ and ‘ravish’ from printed music books and other texts, we can pursue these and other related terms through the tropes and figures of quotidian language. As we shall see, musical enforcement was part of the fabric of early modern conversation, where terms of musical compulsion were applied metaphorically to non-musical responses with regularity, and often in sources otherwise displaying little interest in music. Such allusions were part of everyday parlance, indicating the familiarity of musical delight even away from actual harmony. To explore this circulation, we can turn from printed music books to early modern dramatic dialogue and a range of other sources unrelated to music.

The meaning of ‘music to your ears’ has narrowed considerably since the seventeenth century. Today, the phrase takes music as a welcome, soothing sound: pleasure is at the fore. Yet in early modern usage, there is an equally strong sense that something is music to your ears because it will compel: aptly chosen words can recreate the experience of music – delight – by forcefully and pleasurably possessing the listener’s attention. Thus, in 2 The Honest Whore (PHM, 1605), when Bellafront exclaims, ‘My father? Any tongue that sounds his name, | Speakes Musicke to me: welcome, good old man’ (C3r; 2.1.64–65), her point is that her father’s name seizes her attention, as music would do, as well as giving her pleasure.19 The phrase is used in early modern drama with particularly clear reference to the compulsive effect of music when characters of lower status ask a monarch or figure of power to listen to their pleas. An instance in The Conspiracy of Charles Duke of Byron (CQR, 1608) frames a royal pardon in precisely these terms when the king declares, ‘Tis musique to mine eares: rise then for euer, | Quit of what guilt soeuer, till this houre’ (H3v; 5.2.107–08).20 Byron’s speech is so compelling that it transcends the power imbalance and persuades the king to listen to and accept his words, thus granting the forgiveness requested: royal attention is enforced, as it would be by music. The textual record indicates the phrase’s currency across early modern culture, circulating the idea of musically compelled ears well beyond discussions of harmony. Beside these dramatic examples, variants of the phrase (music to my/mine/your/his/her ears) appear in printed texts ranging from ‘pleasant history’ to accounts of African travel, via translated Italian pastoral drama.21

‘Music to your ears’ is even evoked in non-musical dedications, where it serves a consistent and distinctive rhetorical purpose. In the ‘Epistle Dedicatory’ of a religious pamphlet, Samuel Garey tells Francis Bacon, ‘I know the sound of the trumpet of your praises is no musick to your eares’, whilst in 1636 Francis Gray addresses the various dedicatees of his sermon with almost identical words, protesting, ‘I might not be judged basely to flatter, as knowing that the sou[n]ding out of your Praises is no such pleasing Musicke to your eares.’22 The metaphor contends, in both cases, that whilst others take pleasure in flattery and thus cannot avoid giving it attention, the worthy patron of the text suffers from no such temptation, and can ignore sycophancy with ease. For lesser patrons, perhaps, praise would be music to their ears in replicating the effects of musical delight and pleasurably compelling their attention. But, as Bacon and company give no attention to praise, they will have no experience analogous to musical delight, and so flattery is in no sense music to their ears. These two dedicatory examples are particularly useful in the way they invoke musical delight casually and incidentally: the writers are interested in emphasizing their patrons’ modesty, not in articulating theories of musical affect. By mentioning ‘music to their ears’ in passing, the dedications locate musical compulsion in the linguistic and conceptual frameworks through which subjects encountered their world. The phrase is considered immediately comprehensible in casual invocation, understood fully without foregrounding or explication, as the thrust of the dedicator’s flattery moves quickly on. This is vital in establishing that musical delight was a casual commonplace of the period.

‘Music to your ears’ is generally evoked with earnestness, and often with sycophancy. Dramatic texts take a contrasting tone in their many jokes about musical ravishment, yet they similarly rely upon widespread cultural familiarity with musical compulsion. In one case, Thomas Middleton alludes clearly to musical compulsion whilst indulging in some misogynistic humour in More Dissemblers Besides Women (KM, 1614), when the manservant Dondolo responds to a song by declaring ironically that the performers ‘deserve to be hang’d for ravishing of me’ (E1v; 4.2.83), punning on the sexual and musical senses of the term.23 This pun reappears in a striking passage in S. S.’s The Honest Lawyer (QAM, 1615), in which the gallant Nice shows the servile Thirsty his latest sonnet, intended to seduce his ‘Mistresse’. He advises his man to ‘[l]ay thine eare close to my musicall tongue, I shall rauish her’, to which Thirsty responds, ‘You shall be hang’d for’t then’ (E4v). Nice alludes to the musical ravishment of Thirsty’s ear, gendered female in accordance with its receptive status, whilst Thirsty puns instead upon the separate, criminal act of ravishment, perhaps reassigning ‘her’ to Nice’s ‘Mistresse’ rather than his own ear. To understand the joke, playgoers must be aware that ravishment is a commonly described effect of music; that this is distinct from the sense to which the threat of hanging alludes; and, finally, that the use of the term to describe music draws upon a sense of compulsive irresistibility, producing the gap in meaning upon which the joke depends. This is a common piece of wordplay, repeatedly used in commercial playhouses, indicating an awareness of musical ravishment in early modern culture far beyond specialist thought.

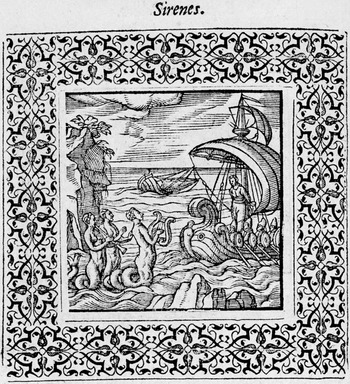

A third and final version of musical enforcement appears in the period’s many references to Sirens. As Linda Phyllis Austern and Inna Naroditskaya have explored, these mythical singers seem to have captured the popular imagination in a broader range of cultural contexts than any other musically compulsive performers: ‘[v]irtually all human cultures seem to have invented myths or tales of enchantment that involve fairy-like stories of water-beings, or at least the cosmic love between some water-woman and an earthly or celestial man’.24 Sirens were widely familiar in early modern culture, Geffrey Whitney’s popular emblem book of 1586 providing a visual example of their circulation (Figure 2).25 Published two decades later, George Chapman’s Bussy D’Ambois (CQR, 1604) outlines the Siren myth as it would continue to circulate in England, when Mountsurry exclaims:

Sirens became early modern shorthand for those able to grasp one’s attention, particularly with their voices. Once again, this presupposes a widespread awareness of the Sirens’ musical compulsion, if the reference is to be understood. Sirens are not the only classical figures connected with forceful music, but they do appear to have been amongst the most widely circulated in early modern England. Sirens illustrate compulsive allure even when unrelated to music in texts as diverse as plays, sermons, children’s textbooks and even (twice) in an account of the lives and deaths of nineteen recently executed pirates.27 The wide familiarity presupposed by this range of genres demonstrates the importance of the Siren myth in circulating the concept of musical enforcement through vernacular culture.

Figure 2 Sirens luring Odysseus with vocal and instrumental music. Geffrey Whitney, A Choice of Emblemes, and Other Deuises (Leiden, 1586), p. 10.

If the pleasure and compulsion of delight was seen as a universal musical response, as appears to have been the case in the early modern period, then the gender specificity of the Siren myth might be problematic. Unlike ‘music to your ears’, Sirens model musical compulsion specifically through female singers and male auditors. Yet intriguingly, Siren references reveal an unexpected and thoroughgoing site of gender flexibility in early modern thought, for the term is readily applied to performers of any gender. Indeed, early modern play-texts are particularly quick to label men as irresistibly persuasive in this way. In A Christian Turned Turk (??, 1610), Voada has no qualms in telling Captain Ward to ‘keepe off false Syren’, when he asks her to ‘[w]ith patience heare me Lady’, telling him, ‘False knight, I haue giuen too calm an eare already | To thy inchanted notes’ (E4r-v; sc. 7.134–42).28 Similarly, in The Two Merry Milkmaids (RB1, 1619) Julia tells Callowe to go ‘[a]way my Lord, I am bound to stop mine eares; the Syrens sing in you’ (F3v; 2.2.315–16).29 Both Voada and Julia invoke the Siren myth casually to describe male characters (Captain Ward and Callowe), in so doing figuring the men as ‘female’ seductive performers and the two woman speakers as ‘male’ seduced receivers. In these examples and elsewhere, musical participants were gendered through the ‘Siren’ label without regard for biological sex.

A neat pair of references occurs in The Renegado (LEM, 1624), when Vitelli, a Venetian gentleman disguised as a merchant, calls the Ottoman lady Donusa ‘this second Siren’ (G4r; 3.5.22), and conversely, Donusa herself notes she has ‘stopte mine eares | Against all Siren notes lust euer sung’ when overwhelmed with desire for Vitelli (D1v; 2.1.29–30). Similarly, in The Turk (CKR, 1607), Muleasses (the titular male character) calls the female Timoclea ‘Syren’ (H3r; 4.1.279), whilst Julia in turn tells Muleasses that ‘Syrens haue left the Sea and sing on shore’ in his voice (I4v; 5.3.10).30 Such parallel invocations of male and female Sirens emphasize the detachability with which this term of musical enforcement could apply to a performer, regardless of sex.

John Marston is particularly playful in invoking sirens in The Malcontent (CQR/KM, 1604), emphasizing gender flexibility through meta-theatricality. A page attending Duke Pietro claims that he has lost his voice ‘[w]ith dreaming faith’, and so offers alternatively ‘a couple of Syrenicall rascals [who] shall inchaunt yee’ (F2v; 3.4.34–37). These ‘Syrenicall’ parts were presumably played by young boys with unbroken voices and thus also likely to perform female roles for the Children of the Queen’s Revels. When Pietro asks them to ‘[s]ing of the nature of women’ (F2v; 3.4.39), gender performativity comes to the fore. This resonates powerfully with the Siren reference: these ‘Syrennicall rascals’ are both male and female, being simultaneously real-life boys, male dramatic characters, seductively female Siren singers, and potential actors of female dramatic parts. The gender flexibility often associated with Sirens in early modern contexts and particularly in drama offers playful comic possibilities to a boy company.

Like Siren song, musical ravishment genders performer and receiver, albeit through a more localized bodily metaphor. Gender roles are interchangeable in the aforementioned ravishment pun taken up by Nice and Thirsty in The Honest Lawyer, with Nice’s instruction to ‘[l]ay thine eare close to my musicall tongue, I shall rauish her’ (E4v, my emphasis). Crucially, Nice genders his male companion’s ear as female in accordance with its receptive role in the process of hearing: the species that Nice’s aural performance generates becomes a metaphoric phallus, as the concrete image of the sound penetrates Thirsty’s ear. Like Siren metaphors, ravishment genders performer and compelled auditor not by anatomy but by role: whether man, woman, boy or girl, all that matters is whether one has a penetrated (female) ear or rather generates a penetrating (male) species. Early modern commentators insist that both men and women can experience musical ravishment, William Corkine referring to his female patrons being ‘ledde away’ by music, and John Northbrooke offers a converse description of music’s ability to ‘rapte and ravishe men in a maner wholy’.31 Andreas Ornithoparchus makes this universality completely explicit in an epistle prefacing his Micrologus, claiming that the ‘power’ of music to delight ‘is so great, that it refuseth neither any sexe, nor any age’.32

Male and female Sirens have profound and useful implications for the early modern relationship between gender and musical compulsion, particularly when considered in conjunction with ravishment. Even whilst Siren analogies gender a performer as seductively female and musical ravishment genders the same performer as obtrusively male, both models apply to performers and auditors of either sex, based solely on the ‘masculine’ penetration or ‘feminine’ allure of ravisher and Siren respectively. This suggests that early modern subjects saw musical gender roles as performed and detachable, rather than inherent, unchanging or determined by biological sex. It is consistent with early modern understandings, then, to think of the response modelled so pervasively, that of compulsion through musical delight, as fully applicable to both male and female musical respondents. In early modern England, anyone could be a Siren. Through this term and the other phrases traced above, the notion of musical compulsion circulated in wider early modern culture as part of the fabric of common parlance.

Delighted Characters

The previous section traced terms of musical enforcement familiar across early modern culture. Now, we can ask what exactly a delighted response to music might involve. Some clues appear in the compelled responses to harmony that were staged with regularity in the playhouse, in which characters often announce their enforced pleasure even as diegetic music sounds. Not only do such dramatizations show what musical compulsion might have looked like, but by presenting this process occurring successfully and repeatedly, they also suggest that such responses were real and familiar in early modern England. Moreover, these dramatizations recur in the repertory of the company with which this chapter is centrally concerned, demonstrating one specific way in which musical enforcement became familiar to the King’s Men’s audiences. A wide range of plays performed by the company include dramatic representations of musical delighting: Philip Massinger and John Fletcher’s The Custom of the Country (1620); Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1611) and Julius Caesar (LCM, 1599); Barnabe Barnes’s The Devil’s Charter (1606); and, the anonymous 1 Jeronimo (1604). We can turn to these plays, then, with a question in mind: what do these dramatic representations suggest about the compelled musical responses of real early modern subjects, particularly their responses in the playhouse?

Perhaps the most striking representation of musical ‘delighting’ occurs in Fletcher and Massinger’s The Custom of the Country. Arnoldo is seeking to establish whether he is being deceived, for various people he does not recognize claim to be his servants. He asks, ‘Good Gentle Sir, give me leave to thinke a little | For either I am much abus’d’ – yet before he can finish this thought, he is hastily interrupted by the music’s organizer, Zabulon, who calls, ‘Strike Musick | And sing that lusty Song’. As the ‘Musick Song’ sounds, Arnoldo’s attention is entirely possessed and his concerns forgotten, leaving him to cry, ‘Bewitching harmony! | Sure I am turn’d into another Creature’ (2B2r; 3.2.57–60).33 This is a remarkably clear dramatic presentation of musical enforcement in action. Without any magical or mythical suggestion within the dramatic world, a character is completely possessed and absorbed by a musical performance, losing the train of thought that overwhelmed him a few seconds previously. His apostrophizing cry, ‘Bewitching harmony!’, indicates that this compulsive delight is emphatically pleasurable, and even suggests that its force is akin to magic in its potency, perhaps evoking the Circe myth in the claim to be turned, or bewitched, into ‘another Creature’.34 From the opposite perspective Zabulon must distract Arnoldo, and relies on music to seize his attention. He is convinced that the performance will have the desired effect, and is not disappointed.

The pleasure and compulsion that delight Arnoldo are stimulating, vivifying and exciting him. Yet the King’s Men also portrayed music relaxing and soothing staged listeners, even causing them to fall asleep. Ariel’s charming of Gonzalo is a familiar example, the sprite first sending Alonso’s adviser to sleep with ‘solemne Musicke’, then awakening him with a song ‘in Gonzaloes eare’, ‘While you here do snoaring lie’ (The Tempest, TLN 862–1009; 2.1.189–310). This is not, however, a unique feature of Shakespeare’s enchanted island; in the decade or so preceding The Tempest’s first performance, music put listeners to sleep in at least two other plays staged by the company. Notably, whilst Ariel’s music appears to have magical properties within the dramatic fiction, these earlier plays offer soporific music as a naturalistic and believable element of their dramatic representation. Julius Caesar, probably first performed around the time that Shakespeare’s company moved to the Globe, sees Brutus call for music from his page, Lucius. After a tender exchange, in which Brutus finds that the book he has been ardently requesting is in fact ‘in the pocket of my Gowne’ and asks Lucius to forgive his ‘forgetfull[ness]’, the page performs ‘Musicke, and a Song’ (TLN 2263–78; 4.2.306–19). The boy actor probably sang and self-accompanied on the lute: David Daniell’s assertion that ‘since no words are given, [it is] probably a melody on a lute’, with Lucius ‘more likely to fall asleep mid-strum than mid-warble’, seems unconvincing, particularly since Tiffany Stern has demonstrated the practical reasons for songs’ words so often being absent from printed play-texts. Moreover, it was far more common in commercial drama for boy actors – such as the player performing as Lucius – to be sent on stage to sing than to perform instrumental music.35 Brutus remarks that ‘[t]his is a sleepy Tune’, but before he can nod off himself he observes that ‘slumber’ has laid its ‘Leaden Mace vpon my Boy, | That playes thee Musicke’ (TLN 2279–81; 4.2.320–22). The page does all he can to stay awake and to play for Brutus as instructed, but cannot resist the enticement to sleep of his own song. Thomas Platter and the many others who watched a performance of this scene at the first Globe may perhaps have been more struck by Caesar’s ghost a few lines later, whilst the staging of an (over)effective lullaby may have seemed so familiar as almost to be banal.36 Yet it is precisely this familiarity that makes the scene such valuable evidence: in dramatizing music’s power to send a listener to sleep, Shakespeare’s play helped circulate delight as part of a wider cultural belief about music, as an expected convention of the early modern stage in general, and as a practice of the King’s Men’s repertory in particular.

In Barnabe Barnes’s The Devil’s Charter, performed by the company a few years later in the mid-1600s, musical compulsion once again sends a listener to sleep, this time in conjunction with a sleeping draught. Music draws drugged victims into a slumber before Pope Alexander the Sixth performs some heavily stylized murders with a pair of asps. Two young brothers, Astor and Philippo Manfredi, enter exhausted from a game of tennis, and lie down upon a conveniently placed bed, where they drink wine drugged with a sleeping draught. Philippo calls for ‘[m]ore musick there’, and ‘after one straine of musicke they fall a sleepe’ as the sounds seize their attention and tip them into a slumber. That this is pleasurable, and that the music has grasped their attention absolutely, is made explicit by Philippo’s declaration ‘[i]n his sleepe’ that his ‘soule is rapt, | Into the ioyes of heauen with harmony’ (I2v-I4r; 4.5).37 In Philippo’s sleepy words, the neoplatonic view of music is reworked as a slumberous rapture in which he dreams of, or perhaps experiences, the ‘divine musics’.38

With the captive brothers asleep, the musicians are duly dismissed. The Pope’s man Bernardo calls ‘musicke depart’, and the stage is set for Alexander’s serpentine malevolence. Alexander immediately ‘stirreth them’, ascertaining that music has helped enforce a sleep so deep that his victims will not awake. Once again, a character successfully relies upon a response of delight, as musical compulsion helps keep the duo asleep whilst he ‘putteth to either of their brests an Aspike’, and instructs the snakes, ‘Take your repast vpon these Princely paps’ (I3r-I4r; 4.5). Barnes’s spectacular stagecraft echoes the musical enforcements staged in Shakespeare’s scenes, music captivating, pleasing and ultimately debilitating youths and adults alike.

Finally, a more prosaic delighting occurs in 1 Jeronimo, using the competing demands of musical compulsion and love to generate dramatic tension. Here, it is military music that compels the attention of a soldier: Andrea is departing for war, and must leave Bellimperia behind. He tells her, ‘the drum beckens me; sweet deere farwell’. She tells him that she wishes to ‘kisse thee first’, but Andrea is drawn once more by ‘[t]he drum agen’. Bellimperia challenges the power of musical compulsion directly, asking, ‘Hath that more power then I?’ Her remark directly acknowledges the musical force that she is competing with. Yet despite the fact he is leaving perhaps for ever, Andrea can no longer ignore the drum in favour of her kiss, and so tells her that she must ‘[d]oot quickly then: farwell’, before promptly exiting. Whilst the sound represents military authority, Andrea refers to ‘the drum’ itself calling him away from Bellimperia’s kiss (D4v).39 Just like the vivifying and soporific examples of Fletcher and Massinger, Shakespeare, and Barnes, this military music seizes attention, drawing Andrea away to war.

These examples, making use of different musical forms, show the diversity of delight: accompanied song likely to be sophisticated art music; instrumental music (or possibly another song); and, a simple drum rhythm.40 Characters respond just as clearly with delight to a complex song setting as they do to military drum signals, one of the simplest sounds that could be considered music. Moreover, these reactions share common features likely to reappear when other early modern characters and subjects are delighted. The blend of compulsion and pleasure is explicit in both Arnoldo and Philippo’s responses, demonstrating the purchase of ‘delight’ as an early modern term for their reactions. Moreover, all of the characters save Lucius (who is busy singing) comment on their own compulsion. This certainly clarifies their responses for playgoers, underlining the importance of musical delighting to each plot. However, it also emphasizes the emotive force of musical delight: two scenes even characterize such outbursts as spontaneous overflows of feeling, in Arnoldo’s apostrophizing and Philippo’s sleep-talking. Such strength of emotion is a hallmark of musical delight.

When asking how and why playhouse performers might seek to compel actual playgoers, one point of continuity amongst these dramatic examples becomes particularly important: many of the musically delighted parties cease what they are doing and saying, and focus completely on the music. Their attention is redirected to the harmony, its source and its significations, and the characters arranging the musical intervention can manipulate them further; in the case of Pope Alexander VI, this has murderous consequences. Significantly, playgoers were themselves targeted by music with precisely this focus of attention in mind: even as play-makers dramatized compelled responses, they also sought to delight their audiences through musical performances, with particular dramatic effects intended. It is to these attempts at playhouse delighting that we can now turn.

Compelled Playgoers

Early modern subjects believed strongly in music’s power to delight, and so playhouse musical engagements were likely to follow these expectations. Whilst direct early modern references to playgoers’ musical responses are rare, Prynne’s claim in Histriomastix that ‘Spectators’ were ‘oft-times ravished’ by ‘obscene lascivious Love-songs’ and ‘ribaldrous pleasing Ditties’ certainly endorses the view that audiences were regularly delighted by music (2L3v). Moreover, if we accept Angela Hobart and Bruce Kapferer’s suggestion that culturally prevalent ideas of musical response can themselves ‘materialize experience’ when practical music sounds, it would seem a valid supposition that quotidian reference to musical compulsion predisposed hearers to respond accordingly, making playgoers more receptive to musical delighting.41

We can also take note of some twenty-first century models of musical affect that resonate productively with the early modern accounts explored above, offering another view of how musical enforcement might work upon a playgoer in Jacobean England. Much recent research in music psychology has examined the phenomenon of ‘entrainment’, a pleasurable, compelled reaction to music that may have been similarly recognizable to an early modern subject. Entrainment ‘describes an action whereby two oscillatory processes interact with one another in such a way that they adjust towards and eventually lock into a common phase and/or periodicity’, for example when ‘[t]he thunder of applause […] turns quite suddenly into synchronized clapping’.42 This encompasses the ensemble of a group of musicians playing in time together, but can also apply to the responses of listeners aligning to the pulse and rhythm of a piece of music. Particularly visible examples of the latter might involve movement in time to the performance, from tapping a foot to dancing a gavotte. Studies of musical entrainment have argued that brains are ‘wired to respond to […] rhythmic sounds in particular’, and that both entrainment and the resistance that, for instance, a syncopated rhythm might provide, are musical experiences particularly associated with pleasure.43 Studies of entrainment offer a suggestion, then, with reference primarily to rhythm, as to how music might ‘delight’ a listener.

Entrainment models one way music might compel listeners in a playhouse, and it also provides a helpful rubric for exploring collective playhouse experience in the synchronization of responses that it describes, be that applause resolving into rhythmic clapping, or audience members together entrained to the rhythm of a musical performance. Without reducing playgoers to an undifferentiated mass, we might think of the moments at which music sounded in the playhouse as points of conjunction where the responses of different playgoers were particularly likely to align, at least in some regards, both with one another and, potentially, with reactions within the diegetic world of a play.

How and why did play-makers seek to compel playgoers with music, then, and what might this suggest about the dramatic significance of playhouse music? Working from the premise that play-makers believed they could delight their audiences, and that this may well have been true, the remainder of the chapter investigates the ways in which playhouse music invited delighted responses, and how these responses would shape playgoers’ wider engagements with drama. Three plays from across the Jacobean period, all performed at the Globe by the King’s Men, make clear attempts to delight playgoers with music: The Revenger’s Tragedy (1606); The Winter’s Tale (1609); and, A Game at Chess (1624). We can begin by asking when in a play it was considered fruitful to evoke musical delight from playgoers.

Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy appeared in print over the winter of 1607–8, its title page claiming it to have ‘beene sundry times Acted, by the Kings Maiesties Seruants’, placing its performances on Bankside prior to the company’s Blackfriars winter residencies.44 Middleton offers two dramatic set-pieces that coincide with the performance of diegetic courtly music: Vindice’s killing of the Duke for murdering his betrothed Gloriana (F3r-v; 3.5.123–223), and Vindice’s killing of the Duke’s son Lussurioso for trying to have sex with Vindice’s sister Castiza (I3v; 5.3.40–42). The scenes share an emphasis on memorable spectacle, the use of court pomp, and the sounding of music as revenge is taken; moreover, in both cases, delighted responses are clear within the dramatic world. In the first instance, violence builds towards a musical climax. The Duke’s murder involves tricking him into kissing the poison-laced skull of the woman he himself poisoned years earlier, then revealing that his wife is having an affair with his illegitimate son, and finally giving him a fatal wound, probably with a dagger. Before the fatal blow is struck, music sounds offstage and the Duchess and Spurio approach:

Vindice

Duke Oh, kill me not with that sight.

Vindice

Hippolito Whist, brother, musick’s at our eare, they come.

Enter the Bastard meeting the Dutchesse.

The offstage music associated with the Duchess grasps the attention of Vindice, his brother Hippolito and the Duke, despite onstage events that we might expect to dominate their concerns: Vindice has already tricked the Duke into kissing the poison-laced skull of Gloriana, and as the music sounds the Duke’s lips and teeth are ‘eaten out’ by the poison (F3r; 3.5.160). As the Duke’s face is dissolving too slowly for Vindice’s liking, however, the revenger directs Hippolito to ‘Naile downe his tongue’ to keep him quiet even as the Duchess approaches (F3r; 3.5.196). Yet despite this striking sequence of events, the brothers are repeatedly drawn to the music as they tell one another to ‘Harke’ and ‘Whist’. Even the Duke is distracted from his own rapidly disintegrating facial features by the musical announcement of his wife and son’s pseudo-incestuous adultery.

The Duchess makes a separate call for ‘Lowdst Musick’ as she and Spurio go in for their banquet. Peter Walls argues that in court performance contexts ‘loud music’ indicated a wind ensemble, likely to be a shawm and sackbut, cornett and sackbut, or possibly even flute and sackbut consort.45 We can surmise, then, that the music sounding offstage – described by Hippolito, too, as ‘lowd Musick’ – may have been performed on wind instruments. As Hippolito and Vindice’s macabre imagery indicates, this music accompanies the Duke’s death:

Duchess Lowdst Musick sound: pleasure is Banquests [sic] guest. Exeunt.

Duke I cannot brooke–

Vindice The Brooke is turnd to bloud.

Hippolito Thanks to lowd Musick.

Vindice

Dramatic characters aside, how might playgoers have responded to this loud music? Within the diegetic world, music draws the Duke’s and the revengers’ attention to the Duchess, exposing her infidelity to her dying husband, but this is not a revelation for playgoers who are already well aware of the affair. Rather, from an audience member’s point of view, music’s principal effect is to highlight a structurally critical moment of revenge, as the Duke’s words (‘brooke’) give way to death (‘bloud’). Hippolito links the murder directly to the music: one is ‘[t]hanks to’ the other. In a play that appears repeatedly and meta-theatrically struck by its own dramatic construction, particularly in its manipulation of generic tropes, Hippolito’s remarks appear to look outward, emphasizing the playwright’s decision to pair compulsive music with the long-awaited death of the Duke. Enforced attention to playhouse music becomes a dramatic tool in the scene, underlining the significance of the gruesome stage actions. Diegetically, characters are similarly preoccupied with the music, to some extent modelling compelled responses to non-diegetic hearers even as their relationships with the music and its signification remain distinct from the engagements of playgoers beyond the dramatic world.

Vindice’s second stab at revenge occurs in the final scene, when he and his accomplices perform a masque for the new Duke Lussurioso and his sycophants:

Enter the Maske of

Reuengers, the two Brothers, and

two Lords more.

[…]

The Reuengers daunce:

At the end, steale out their swords, and these foure kill the foure at the Table in their Chaires. It thunders.

Vindice Marke, Thunder?

The revengers enter and dance before enacting wild justice with their swords, a visually striking combination of violence, choreographed movement and (presumably) masque costumes. Once more, music – this time for a masque – is intended to cause delight, compelling attention to the stage performance and foregrounding another significant narrative development. Musical delight is again dramatized even as it is sought from playgoers, for Lussurioso and his courtiers are compelled by the masque long enough for Vindice to kill them. Playgoers have a radically different understanding of what is occurring, having heard Vindice outline his plan in minute detail to his co-conspirators in the preceding scene: Lussurioso is compelled to watch what he believes is simply a court entertainment; playgoers, however, have their attention drawn to what they know will shortly become a bloodbath. Middleton plays upon the tropes of revenge tragedy here, as in the earlier scene, but his masque of revengers also typifies how music was used to direct playgoers’ attention in Jacobean commercial drama: moments of musical delighting have a structural significance to the plot; the precise sounding of their music usually correlates with a visually appealing piece of stage spectacle; and, the importance of this music was sufficiently clear to textual producers that they bothered to record stage directions (either separate, or embedded and extremely explicit). The play includes musical delight in its final scene both upon the stage and – if it is effective – across the rest of the playhouse, compelling playgoers’ attention to the drama at a moment of narrative significance.

Middleton’s last work for the commercial stage, A Game at Chess, is a complex topical satire representing contemporary politics in terms of chess pieces. The play repeatedly seeks to delight playgoers, in scenes sharing several features with Vindice’s acts of vengeance. Chess was a smash hit, with early title pages claiming a run of ‘nine days to gether at the Globe on the banks side’ in August 1624.46 As one of the most scandalous and most popular pieces of commercial drama brought to production in the Jacobean period, the play is particularly helpful to this investigation; most obviously, its popularity implies success in performance at the Globe, and it is helpful (and unusual) to know that a play was as gripping for first audiences as it is central to later critical endeavour. Furthermore, the whirl of discussion that the play generated – much of which survives in letters and other documents – allows us a clearer than usual sense of what interested early audiences. These contemporary reports refer directly to ‘popular opinion’ of the play, indicating what early witnesses found particularly significant. With a sense, then, of the dramatic moments most likely to have particularly interested playgoers, we can pursue the ways in which playhouse music might contribute to Middleton’s dramatic structure.

John Holles, politician and Nottinghamshire landowner, describes contemporary interpretations of A Game at Chess in a letter to the Earl of Somerset following his own eye-witness experience. He is clear that ‘ye descant [of the play] was built uppon ye popular opinion, yt ye Iesuits mark is to bring all ye christian world vnder Rome for ye spirituality, & vnder Spayn for ye temporalty’.47 Holles recognizes that ‘ye poet’ Middleton echoes a truculent ‘popular opinion’ of Spanish Jesuitism fuelled by the pamphlets of Thomas Scott.48 Indeed, his musical metaphor is particularly resonant in its suggestion that Middleton is embellishing and improvising on top of a clear and established view, just as a musical descant, in the sense used here, would be extemporized over the plainsong.49 Holles’s suggestion is confirmed in the play’s induction, where Middleton makes explicit that the Black House represents a seductive threat of ever-spreading Catholicism, or, more specifically, Jesuitism. The sixteenth-century founder of the Society of Jesus, Ignatius Loyola, appears before the start of the play proper to express surprise that his ‘Disciples’ have not yet ‘spread ouer the World […] | Like the Egyptian Grasse-hoppers’, describing the black pieces as ‘the children of my cunning’ (B1r-v; Induction.4–51). Through this frame, Middleton instructs playgoers to read the ‘diuilish plotts and deuices’ of the Black Knight and his colleagues as seductive, imperialist attempts at Catholic conversion.50 It follows, then, that structurally key scenes will include the points at which the Black House project succeeds or fails.

A Game at Chess follows a typical Jacobean dramatic narrative structure, with two separate plot strands – or a main plot and subplot – dealing with related themes and subject matter, one in relation to characters of lower social status than those involved in the other. The two strands interrelate by offering complementary versions of attempted conversion to the ‘Spanish Catholic’ side – ‘ye descant’ of the play – enacted through various forms of seduction and dissemblance. Given the persistent theme of Catholic temptation, playgoers would see the Black Bishop’s Pawn’s attempted seduction of the White Queen’s Pawn as parallel to the Black Knight’s invitations for the White Knight to join the Black House. The two plots subtly mirror one another throughout, as White House pieces are tempted to convert, only to escape at the last moment, preserving their ‘innocent’ status. In each plot, both the moment of temptation and the moment of escape is accompanied by music that seeks delighted, compelled attention from playgoers.

The temptation and escape of the White Queen’s Pawn take place in acts three and four. She is of low status, both as a character and as a chess piece, yet nonetheless presented as important: she is the most vocal member of the White House (only the Black Knight has more lines), and she delivers the epilogue. Earlier in the play, the Black Bishop’s Pawn attempts first to seduce and then to rape her, before teaming up with the Black Queen’s Pawn in act three, tempting the white piece with supposed magic. The Black Queen’s Pawn begins by convincing her opposite that powerful incantations will conjure the likeness of her future husband in a mirror. The incantations are first answered with ‘sweet notes’, described as ‘the ayre inchanted with your prayses’, before the Black Bishop’s Pawn enters, ‘stands before the glasse’ and leaves (G2v; 3.1.394–95.iii). The White Queen’s Pawn, forbidden to turn around, readily accepts that she has seen an apparition of her destined partner in the mirror. Deceived, she agrees to the Black Queen’s Pawn’s suggestion: sexual union with the Black Bishop’s Pawn. Her agreement is as critical to Chess as is Vindice’s revenging to Middleton’s earlier play. Moreover, just as Lussurioso was compelled by Vindice’s masque, so the White Queen’s Pawn is delighted by the ‘sweet notes’ and supposed apparition. Outside of the dramatic world, playgoers are not deceived by musical delight, but rather have their attention directed to the music and the concurrent stage spectacle. Audience members have a markedly different understanding of and relationship to the music than that of the delighted stage character, yet once again musical enforcement works both diegetically and non-diegetically to shape the engagements of character and playgoer alike. This technique of simultaneous delighting is used systematically in A Game at Chess, just as it recurs across scenes of revenge in Middleton’s earlier play.

Music is not cued again until 4.3, when the three pawns meet at night to enact their several intentions:

Recorder.

Dumb shew.

Enter Blacke Queenes Pawne with a light, conducting the

White Queenes Pawne to a Chamber, and fetching in the Blacke

Bishops Pawne conueyes him to an other, puts out the light, and

followes.

Several of the early texts specify music for this dumb show; indeed, music for dumb show was conventional, as is clear from Thomas Heywood’s direction in The Golden Age (QAM, 1610) to ‘[s]ound a dumbe shew’ (K2v).51 There is much at stake here for playgoers sympathetic to the White House, for the Black Queen’s Pawn’s deception of both the White Queen’s Pawn and the Black Bishop’s Pawn has been established in her earlier aside, ‘ile enioy the sport, and cousen you both’ (H1v; 4.1.148). Playgoers do not know, however, that her specific intention is to trick her Black House colleague into her own bed. The loss of the White Queen’s Pawn’s virginity remains a plausible outcome until finally, having ‘fetch[ed] in the Blacke Bishops Pawne’, the Black Queen’s Pawn ‘conueyes him to an other’ room and follows him in herself (H4r; 4.3.0.vi-viii). Only at the conclusion of this scene do playgoers understand that the White House representative has escaped the Black Bishop’s Pawn’s bed.

Unlike the music earlier invoked by the Black Queen’s Pawn in front of the mirror, or indeed that of Vindice’s masque at the denouement of The Revenger’s Tragedy, this is non-diegetic music, audible to playgoers but not heard by the characters. In scenes of diegetic music, harmony’s effects are usually important within the dramatic world, seducing the White Queen’s Pawn in front of the mirror, or grasping first the Duke and then Lussurioso’s attention, even whilst that same music acts upon playgoers outside the dramatic world, compelling their attention to critical moments of plot development. In this dumb show, however, the recorders play solely to affect playgoers, as the characters cannot hear the music. This is a particularly significant example of enforcement, then, because Middleton and the King’s Men aim exclusively at delighting their audience: this is categorically about playhouse response, rather than fictionalized reactions. Other instances, as we shall see, pursue more sophisticated interactions between playgoer delight and character delight, but by exploiting only the former, this scene makes particularly clear how compulsive music shaped playgoer engagements with dramatic performance.

The White Knight’s plot follows similar contours to that of the White Queen’s Pawn’s. In deference to his status, his story concludes the play itself, reaching its climax after the White Queen’s Pawn’s escape in the fourth act. The same pattern of musical delighting recurs in this ‘main’ plot, with a pair of musical cues. The fifth act begins as the White Knight and Duke arrive at the enemy court, having accepted an invitation to ‘see, | The Black-house pleasure, state and dignitie’ (H4v; 4.4.45–46). The Black Knight makes his definitive attempt to convert his white counterpart in the scene, beginning with a spectacular greeting. This stylized invitation to switch sides is the most significant proposition of the entire play, given the status of the White Knight relative to the White Queen’s Pawn and the positioning of this moment at the start of the final act (I2r-v; 5.1.1–50). The scene culminates in a song ‘[t]o welcome thee, the faire White House Knight, | And to bring our hopes about’, followed by quickened statues dancing around an altar (I2v; 5.1.37–46). This recalls Vindice’s masque as well as the Black Queen’s Pawn’s mirror in its combination of delighting music and visual spectacle. The lengthy musical performance that accompanies the statues both compels attention and, as it continues, creates tension by deferring the White Knight’s response. Fittingly for such a structurally significant moment, this could be the most powerful instance of musical delighting in the entire play. Just as in the subplot, however, playgoers are made to wait for an outcome: the music and the scene conclude with the White Knight’s reply unvoiced.

Not until the final scene does the plot reach its conclusion, and it does so in a further moment of musical enforcement. Before giving his answer, the White Knight first suggests that he is receptive to the advances. He confesses to a series of increasingly serious vices, each of which is warmly welcomed by the Black Knight. Upon reaching the ‘hidden’st poyson’ of all his faults, that he is ‘an Arch-dissembler’, he draws an eager confidence from his counterpart: ‘What we haue done, has bin dissemblance euer’ (K2v-K3r; 5.3.71–159). With this admission, the White Knight gives his ultimate response:

White knight

As the White House triumphs, music captivates playgoers’ attention for the fourth time with a ‘flourish’ supported by ‘a great shout’, adding brief yet powerful musical compulsion to the precise moment at which the White Knight’s rejection of Black House deception is confirmed, and the chess game ends.52 As in the White Queen’s Pawn’s plot, the early texts cue no music between the tempting dance and song and the final compulsive flourish of escape, giving further prominence to these sounds.53 With surgical precision, Middleton and the King’s Men shape a soundscape in which musical delight guides playgoers through the complex, mirrored narrative structure and remarkably abstract staging of the White Knight’s escape and the White Queen’s Pawn’s subplot. The play was written for a Globe audience, and it clearly tapped into popular political feeling to achieve unprecedented popularity at that playhouse. Certainly, early modern subjects went for the satire rather than the music, yet the fact that the playhouse filled to capacity day after day until the play was suppressed indicates the success of this dramatic work in performance. Musical delight is central to its dramaturgy, helping the play succeed by compelling playhouse attention at four significant narrative moments.

In light of the musical delighting in Middleton’s Game at Chess and Revenger’s Tragedy, one moment stands out from a familiar Shakespearean text composed between the two plays. At the conclusion of The Winter’s Tale, Paulina reanimates the statue of Hermione with the command, ‘Musick; awake her: Strike’ (TLN 3306; 5.3.98). Playgoers’ responses to this music are critical to the success of the scene in performance; indeed, this moment is so central to the overall shape of the play that the whole work’s impact is to some extent defined by the level of this success. Russ McDonald argues that ‘[w]hat distinguishes The Winter’s Tale is that much of the poetic language is organized periodically: convoluted sentences or difficult speeches become coherent and meaningful only in their final clauses or movements’, and a ‘similar principle governs the arrangement of dramatic action: the shape and meaning of events become apparent only in the final moments of the tragicomedy’. Thus, ‘the play […] surprises us, denying us knowledge of Hermione’s survival until the very end of the work, challenging our confidence in our superior understanding and thus transforming our comprehension of the world we thought we knew’.54 As McDonald shows, much weight is brought to bear upon the statue and its reanimation: only in this moment do playgoers learn that Hermione lives, and that the narrative can conclude with a final reconciliation. We might add to this the ‘suspension’ of action in the previous scene (5.2), when resolutions including the father-daughter meeting are only reported verbally, allowing the fully mimetic representation of Hermione’s return to have maximum impact and enact the ‘discharge’ of reconciliation at precisely the same point as the narratorial ‘discharge’ that McDonald identifies: when music sounds and the statue moves.

Music appears at a key playhouse moment in The Winter’s Tale, occupying a ‘dramatic position’ at ‘the climax of the play’ just as it does in the closing scenes of Middleton’s plays.55 Once again, if successful the music ‘[d]elights the sences’ and ‘captiuates the braines’ of playgoers, compelling their attention to a piece of dramatic representation of particular fabular significance.56 At this moment, the suspension of knowledge of the plot is relieved as Hermione moves, and the suspension of reconciliation is discharged, with the previous scene’s narrative accounts upstaged by a moment of mimesis. Music draws playgoers’ scattered attention to a single symbolic moment of stage business, metonymically enacting the many reversals upon which the conclusion of the narrative depends. The play then concludes somewhat hastily within sixty lines, allowing for little more than verbal acknowledgement of the reconciliations contingent upon Hermione’s survival. Until this point playgoers are denied the knowledge that such a reconciliatory conclusion is even possible, let alone likely; thus, musical compulsion is required to support an abrupt end with a sharp, even jarring, shift in dramatic direction. Shakespeare’s precise use of delighting music is structurally analogous to that of the closing scenes in A Game at Chess and The Revenger’s Tragedy, all three plays using musical delight to draw playhouse attention to their narrative climax. Intriguingly, the constants in all three examples are the playing company performing, and the playing space of the Globe. Personnel including company members, playwrights and playgoers changed between 1606 and 1624, yet the King’s Men appear to have delighted playgoers with music at the Globe throughout the Jacobean period.

The Sound of Delight

Early modern play-texts are generally much better at indicating when music was played than what that music sounded like, and we have already seen how clearly the structural location of music cues can be preserved in printed playbooks. This is not to say, however, that more specific features of particular cues cannot be pursued as well. Whilst our knowledge of dramatic music must always be recognized as partial, we can establish more from the textual record than might be expected about the music used for playhouse delighting. Moreover, some of these aural choices reveal further dramatic nuances, again emphasizing the significance of musical delight to Jacobean play-makers. This section will investigate instrument choices and, more speculatively, possible formal features of delighting music.

Four moments of musical compulsion in A Game at Chess indicate the range of instruments that were believed to compel playgoers, also offering textual clues as to why particular instruments might be appropriate in particular contexts. This varied music echoes the diversity of diegetically delighting sounds used by the King’s Men in The Custom of the Country, The Tempest, Julius Caesar, The Devil’s Charter and 1 Jeronimo. As we have seen, the two plot strands of Chess each begin with a moment of Black House seduction supported by musical compulsion (3.1; 5.1), and follow this with a moment of White House escape accompanied by delighting music (4.3; 5.3). The previous section considered the two plot strands separately, but here we can pair analogous moments: the seduction of the White Queen’s Pawn matches the temptation of the White Knight; her dumb show escape is echoed in his concluding ‘checke mate | By discouery’ (K3v; 5.3.160–61). The climaxes of the two plots, in scenes 4.3 and 5.3, illustrate the contrasting instruments that could evoke musical delight.

Scene 4.3 is a dumb show without dialogue and set at night, indicated to the audience by the Black Queen’s Pawn’s use of a taper when ‘conducting’ the other characters to separate chambers (H4r; 4.3.0.i). Recorders support this wordless, supposedly dark scene, the instrument noted in both 1625 quarto editions of the play as well as the Bridgewater and Rosenbach manuscripts.57 The instrument’s mellow tone and gentle attack are reflected in Gary Taylor’s addition that the recorders are ‘within, playing soft music’ (4.3.0.i), following Alan C. Dessen and Leslie Thomson’s suggestion that such music was associated with the instruments.58 In an early modern context ‘soft’ did not simply mean ‘quiet’; Peter Walls notes, for instance, that the call for ‘a soft musique of twelue Lutes and twelue voyces’ in Samuel Daniel’s Tethys Festival masque ‘is probably intended to indicate something about sophistication and quality rather than volume’.59 Taylor’s addition is therefore apt in supporting the sentiment of the dumb show: this is a performance of gentle and probably quite sophisticated music for recorder consort, to accompany a night scene.

The analogous scene in the White Knight’s plot is far more emphatic, with his claim of ‘checke mate | By discouery’ indicating White House victory in the chess game. Accordingly, it uses not recorders but a ‘great shout | and flourish’: a trumpet fanfare that compels attention to a final, decisive narrative turn (K3v; 5.3.160–62.i). There could not be a more contrasting choice of instruments for the two moments of musical delight, indicating the range of musical sounds expected to compel playgoers. This seizing of attention reflects an attraction to harmony – a culturally reinforced desire to engage closely with musical sound – rather than certain instruments’ abilities to shock, or to drown out other noises. For early modern play-makers, both gentle recorder music and a sharp brass fanfare could equally compel attention during critical stage business, with either sound world available to help focus playhouse attention. Recorders fit the stealthy atmosphere of the dumb show even as they compel playgoers, whilst a brass flourish evokes a similarly delighted response in keeping with a vivacious, cacophonic final scene of triumph and bagging. Moreover, recorders are well suited to sustained, continuous playing during the important yet somewhat convoluted movements of the pawns, requiring ongoing playhouse attention. In contrast, a short, sharp fanfare is far more appropriate to accompany the four (or three) words that mark the moment of victory in the final scene, ‘checke mate | By discouery’ (K3v; 5.3.160–61). Even in their length, then, these two cues are differently appropriate for contrasting dramatic contexts, yet could be equally compelling.

The temptation scenes that respectively precede bed trick and bagging introduce further sounds. As explored above, the Black Queen’s Pawn’s mirror deception (3.1) corresponds to the Black Knight’s song and dancing statues (5.1): these are Black House attempts to convert, or overcome, the White House pieces. There are significant similarities between the scenes, from which we can make further suggestions about the sounds of delighting music. First, both rely on spectacle. The White Queen’s Pawn looks in what she is repeatedly told is a ‘Magicall glasse’, and sees the Black Bishop’s Pawn ‘like an Aparitian’ (G1r-G2v; 3.1.329–95.i). As she has been forbidden to turn round, she does not share the playgoers’ knowledge that he enters the stage and stands behind her in the flesh. Likewise, the Black Knight’s presentation ‘[t]o enlarge’ the White Knight’s ‘welcome’ concludes visually with the dance of the statues, apparently ‘[q]uickned by some Power aboue, | Or what is more strange to show our Loue’ (I2v; 5.1.37–46). Both uses of spectacle accompany Black House claims that supernatural forces are at work, invoking ‘some Power aboue’ (I2v; 5.1.45), and the ‘powerfull name […] | of the mighty blacke House Queene’ (G2r; 3.1.370–72). Significantly, the music that delights playgoers and prompts ‘supernatural’ spectacle is song in both instances; indeed, the music of the mirror scene is described in detail by the Black Queen’s Pawn before it sounds. She invites her white counterpart to listen, as:

Such ‘Vocall Sounds’ reappear in the Black Knight’s welcome of 5.1: he describes ‘sweet-sounding aires’ from ‘all parts’ as he introduces the song, ‘Wonder worke some strange delight’ (I2v; 5.1.31–46), the words of which are preserved in the text. Where the conclusions of the two plots used contrasting musical sound worlds to evoke delight, then, the preceding temptation scenes actually share an aural register of vocal performance as they attempt to compel playgoers.

Middleton and the King’s Men may have considered vocal performance particularly compelling, given its appearance at two separate moments of narrative significance. Moreover, there may be yet more specific dramaturgical intentions behind the choice of vocal music: perhaps the shared soundscape of the two temptation scenes is intended to shape playgoers’ understandings of the two plots’ interrelationship. Structure is significant here, for the vocal performances are the first and third of four key moments of musical delighting, and the intervening dumb show (4.3) has the completely different sound of recorders. By returning in the final act to ‘Vocall Sounds’ similar to those used two acts previously, the welcome song can recall the mirror scene and avoid recalling the more recent musical delight of the recorders. The shared sound of vocal performance means the seizing of playgoers’ attention at the Black House court will not evoke the sound of the White Queen’s Pawn’s escape, but rather that of the Black Queen’s Pawn’s earlier tempting. The aural connection is supported by other continuities: not only did the mirror temptation sound similar as it evoked delight from character and audience, but it looked equally spectacular, and the Black Queen’s Pawn made analogous claims of supernatural activity. The shared vocal sounds make one scene a precedent for the other, and this would have concerned an early audience. In the first scene, the White Queen’s Pawn is deceived by the display and only avoids the loss of her virginity thanks to her counterpart’s desire for the Black Bishop’s Pawn. The possibility of a similarly naïve White Knight repeating her mistake alongside sounds echoing those of the mirror scene would build dramatic tension before he makes his ultimate escape. Thus, the experience of musical delight in act five tells playgoers something about the possible direction of the plot: in Middleton’s climatic ceremony of the horsemen, even echoes of a tempted pawn can carry narrative significance. Music thus shapes meaning at the conclusion of the play through instrumentation that binds together the delightful sounds of two separate scenes, encouraging playgoers to engage carefully with every component of playhouse performance including music.

The sole textual witness to The Winter’s Tale, the 1623 Folio, has far less to tell us about instrument choices than do the multiple manuscript and print versions of A Game at Chess. But whilst recovering delighting sounds in The Winter’s Tale is by no means straightforward, we can nonetheless make some informed suggestions as to the King’s Men’s musical decisions. We lack textual detail beyond the word ‘Musick’ when considering what was originally played, but through close consideration of the contents of the scene, of the play’s early stage history at court and at the Globe and of other plays in the King’s Men’s repertory to 1609, a hitherto unexplored musical possibility emerges.61 In the final scene of The Winter’s Tale, music is given the apparent diegetic power to compel life into an inanimate statue. It is long established that the scene bears strong similarities to the description of animated statues found in a hermetic-alchemical text well known in Jacobean England: Frances A. Yates avers that ‘[i]t seems obvious […] that Shakespeare is alluding […] to the famous god-making passage in the Asclepius’. Named for the classical god of healing (himself renowned in some traditions for performing resurrections, including that of Hippolytus at the request of Artemis), the Asclepius was part of the Corpus Hermeticum. This group of writings was attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, who was revered by alchemists as their founder, and whose name is perhaps even echoed in Hermione’s.62 Yates refers to a much-studied passage describing Egyptian ‘statues […] made alive by consciousness, and […] filled with breath. They do mighty deeds. They have knowledge of the future […] They bring illnesses to men and cure them’. The nature of these ‘terrestrial’ gods ‘is derived from herbs, stones and spices’, and ‘[b]ecause of this these gods are delighted by frequent sacrifices’, as well as by ‘hymns, praises and sweet sounds in tune with the celestial harmony’.63 The statue of Hermione certainly fulfils the criteria to be a ‘terrestrial’ god; most significantly here, it comes to life in response to ‘sweet sounds in tune with the celestial harmony’, when Paulina calls for music.

Significantly, The Winter’s Tale is not the only Shakespearean text that alludes to Asclepian musical animation. Shakespeare and George Wilkins’s Pericles, Prince of Tyre (KM, 1608), a staple of the King’s Men’s later 1600s repertory, includes a similar musical resurrection that draws yet more explicitly upon hermetic-alchemical ideas. This time, it is the corpse of Thaisa, Pericles’s wife, that the physician Lord Cerimon works frantically, and ultimately successfully, to revive, she having washed ashore in a coffin:

Cerimon

Cerimon is extremely clear that music is key to this resurrection. Just as in The Winter’s Tale, then, here the King’s Men stage compulsive musical resurrection at a key moment in which a dead character is given new life. Cerimon’s request that ‘Escelapius guide vs’ is a prayer to the Classical god of healing, but it also gestures towards the hermetic-alchemical text of musical animation that bears the god’s name as its title: Asclepius. Cerimon’s words and the nature of Thaisa’s resurrection indicate that Wilkins, Shakespeare and the King’s Men were familiar with the hermetic-alchemical model of musical animation by 1608. The delight mythologized both in Pericles and The Winter’s Tale, then, takes an exceptionally specific form, that of hermetic-alchemical resurrection through music.

If both Pericles and The Winter’s Tale include scenes of Asclepian resurrection, perhaps extant hermetic-alchemical texts can help us identify a musical form that would have been appropriate for use in early performances of The Winter’s Tale. The reference in Pericles to ‘rough and | Wofull Musick’ is a helpful first step towards identifying appropriate musical forms for scenes of musical resurrection, but as F. Elizabeth Hart notes, Cerimon’s request is suggestive rather than specific. More recently, B. J. Sokol has traced musical styles of the period that might be associated with these adjectives, concluding that works by Gesualdo, Monteverdi and Dowland could ‘provide models for the styles we are seeking’. However, neither in this claim, nor in his suggestion that ‘[i]n accord with Hermione’s inward as well as outward Majesty, the music that Paulina commands for Hermione’s entry music would most appropriately be magnificent, perhaps a tucket or fanfare’, does he explore the possibility that music with Asclepian resonances sounded in either play.65