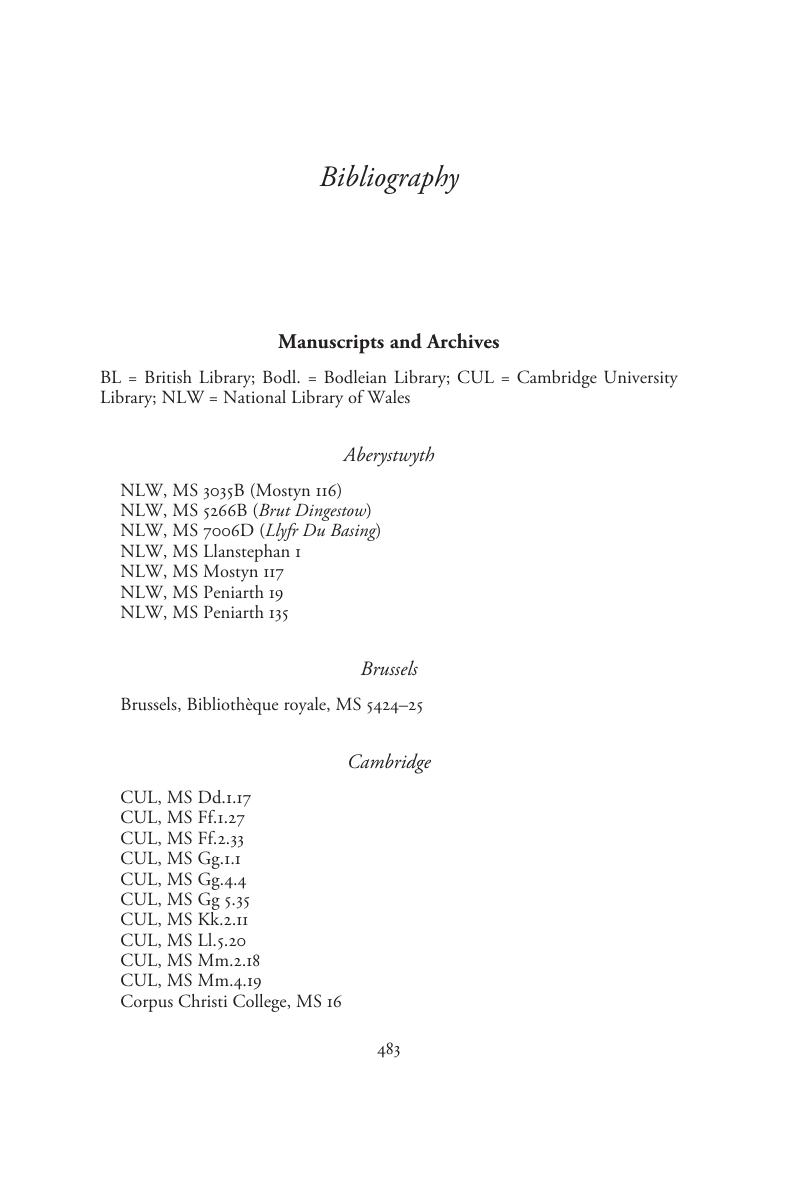

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 December 2019

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Medieval Historical WritingBritain and Ireland, 500–1500, pp. 483 - 562Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019