Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Murder Most Foul

- I Murder on Trial: Justice, Law and Society

- II The Public Hermeneutics of Murder: Interpretation and Context

- III Murder in the Community: Gender, Youth And Family

- Conclusion

- Select Bibliography

- Index

Introduction: Murder Most Foul

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 July 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Murder Most Foul

- I Murder on Trial: Justice, Law and Society

- II The Public Hermeneutics of Murder: Interpretation and Context

- III Murder in the Community: Gender, Youth And Family

- Conclusion

- Select Bibliography

- Index

Summary

GHOST: Revenge his foul and most unnatural murder.

HAMLET: Murder?

GHOST: Murder most foul, as in the best it is, But this most foul, strange, and unnatural.

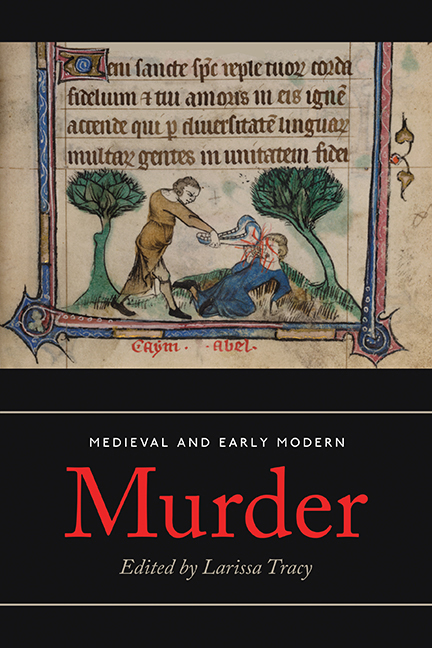

(Hamlet I.v.26–9)THE GHOST'S WORDS, urging his indecisive son to vengeance, reverberate throughout the corpus of Western literature and popular culture. The 1964 film adaptation of Agatha Christie's Mrs. McGinty's Dead (1952) draws its title from these fateful words, luring audiences into a classic whodunnit featuring Miss Jane Marple as the intrepid amateur sleuth, replacing Hercule Poirot in the book. The phrase ‘murder most foul’ has become an idiomatic, even parodic, catchphrase for referring to cases of homicide. It evokes the dark shadows of Elizabethan drama, the stock murders of pulp fiction and detective novels and the reams of ‘true crime’ studies about serial killers like Jack the Ripper and H. H. Holmes. However, Shakespeare's iconic phrase captures the insidious nature of this most heinous crime – a crime that has enthralled and horrified societies for centuries. The earliest surviving prohibition of murder occurs in the Sumerian law codes of Ur-Nammu (c. 1900 BCE), the first complete law code in the world, which demands the ultimate penalty: ‘If a man commits a murder, that man must be killed.’ Murder has always been a feature of human society, recorded not only in the earliest law codes like those of Ur-Nammu, but also present in the archaeological record – 430,000 years ago, an early Neanderthal was beaten around the face with a blunt object and thrown down a cave system in Atapuerca, Spain, where he stayed until 2014 when his remains were discovered among those of twenty-eight other individuals. Biblical tradition claims that the ‘first’ murder was that of one brother by another with the jawbone of an ass – Cain and Abel – out of envy and spite. Chronicles record numerous murders and assassinations amid accounts of battle and warfare. Murder ‘reads the community in which it takes place, calling all relationships into question – mother and infant, husband and wife, lovers, friends, strangers, and mere acquaintances – and posing troubling questions about the moral nature of humankind’.

Modern popular culture makes a killing on murder: crime dramas, true crime, serial killers, detective stories, court-room escapades in novels, films, television series, news and social media. It intrigues and entertains.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Medieval and Early Modern MurderLegal, Literary and Historical Contexts, pp. 1 - 16Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2018