Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Highlighting Migrant Humanity

- Chapter 1 Ngezinyawo - Migrant Journeys

- Chapter 2 Slavery, Indenture and Migrant Labour: Maritime Immigration from Mozambique to the Cape, c.1780–1880

- Chapter 3 Walking 2 000 Kilometres to Work and Back: The Wandering Bassuto by Carl Richter

- Chapter 4 A Century of Migrancy from Mpondoland

- Chapter 5 The Migrant Kings of Zululand

- Chapter 6 The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

- Chapter 7 The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

- Chapter 8 ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

- Chapter 9 ‘Stray Boys’: The Kruger National Park and Migrant Labour

- Chapter 10 Surviving Drought: Migrancy and the Homestead Economy

- Chapter 11 Migrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

- Chapter 12 Verwoerd's Oxen: Performing Labour Migrancy in Southern Africa

- Chapter 13 ‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu's Envelopes

- Chapter 14 Sophie and the City: Womanhood, Labour and Migrancy

- Chapter 15 Bungityala

- Chapter 16 Migrants: Vanguard of the Worker's Struggles?

- Chapter 17 Debt or Savings? Of Migrants, Mines and Money

- Chapter 18 Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Index

Chapter 18 - Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 July 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Highlighting Migrant Humanity

- Chapter 1 Ngezinyawo - Migrant Journeys

- Chapter 2 Slavery, Indenture and Migrant Labour: Maritime Immigration from Mozambique to the Cape, c.1780–1880

- Chapter 3 Walking 2 000 Kilometres to Work and Back: The Wandering Bassuto by Carl Richter

- Chapter 4 A Century of Migrancy from Mpondoland

- Chapter 5 The Migrant Kings of Zululand

- Chapter 6 The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

- Chapter 7 The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

- Chapter 8 ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

- Chapter 9 ‘Stray Boys’: The Kruger National Park and Migrant Labour

- Chapter 10 Surviving Drought: Migrancy and the Homestead Economy

- Chapter 11 Migrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

- Chapter 12 Verwoerd's Oxen: Performing Labour Migrancy in Southern Africa

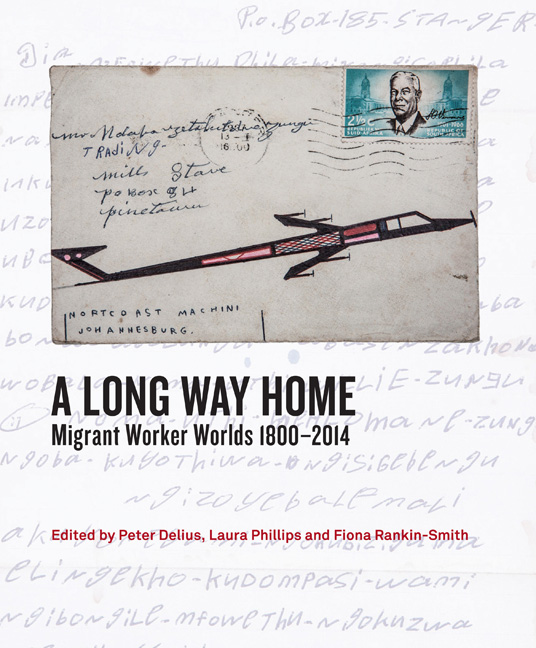

- Chapter 13 ‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu's Envelopes

- Chapter 14 Sophie and the City: Womanhood, Labour and Migrancy

- Chapter 15 Bungityala

- Chapter 16 Migrants: Vanguard of the Worker's Struggles?

- Chapter 17 Debt or Savings? Of Migrants, Mines and Money

- Chapter 18 Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Index

Summary

The graphic footage of South African police gunning down striking mineworkers in the veld surrounding the town of Marikana stunned both the country and the world. It was the bloodiest confrontation between police and civilians since the end of apartheid and the climax of days of stand-offs, which had already left several dead. In the weeks following the massacre of 16 August 2012 – a day widely heralded as the post-apartheid Sharpeville moment – wildcat strikes sent shock waves throughout the country's crucial mining sector. Unrest spread like a veld fire from the platinum mines of the North West to other mines throughout the country, especially in the gold sector, with strikers taking up the simple demand of the Marikana workers – a living wage of R12 500 per month, more than double what most were getting at the time. Despite mass arrests, threats of dismissal and alleged police torture, the Marikana strikers continued to stay away from work. Eventually, more than a month after the massacre, they settled on a 22 per cent wage increase which, though less than the R12 500 they were calling for, still amounted to a substantial gain. It was also an encouraging sign to striking workers elsewhere who were breaking ranks with the dominant National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) en masse and joining the rival Association of Mining and Construction Workers’ Union (Amcu), a hitherto little-known, nonpartisan workers’ organisation. The latter originated in Mpumalanga as a breakaway from NUM and at the time of the massacre was widely depicted as a shady upstart by its detractors.

By the end of the year, unrest on the mines had died down, but the events had exposed major rifts within the working class and within South African society at large. Nothing captured the political perplexity of the postapartheid denouement quite like NUM founder-turnedbusiness- tycoon and soon-to-be deputy ANC president, Cyril Ramaphosa, condemning the actions of the Marikana strikers as ‘plainly and dastardly criminal’ in email correspondence. He wrote those words as a board member of Lonmin, the owner of the Marikana mine, and they no doubt left a bubbling sense of resentment among those who had gathered on the Marikana koppie, many of them seasoned labourers who knew NUM during the apartheid years as an ambitiously militant union led by the charismatic young Ramaphosa.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Long Way HomeMigrant Worker Worlds 1800–2014, pp. 254 - 263Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2014