Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Highlighting Migrant Humanity

- Chapter 1 Ngezinyawo - Migrant Journeys

- Chapter 2 Slavery, Indenture and Migrant Labour: Maritime Immigration from Mozambique to the Cape, c.1780–1880

- Chapter 3 Walking 2 000 Kilometres to Work and Back: The Wandering Bassuto by Carl Richter

- Chapter 4 A Century of Migrancy from Mpondoland

- Chapter 5 The Migrant Kings of Zululand

- Chapter 6 The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

- Chapter 7 The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

- Chapter 8 ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

- Chapter 9 ‘Stray Boys’: The Kruger National Park and Migrant Labour

- Chapter 10 Surviving Drought: Migrancy and the Homestead Economy

- Chapter 11 Migrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

- Chapter 12 Verwoerd's Oxen: Performing Labour Migrancy in Southern Africa

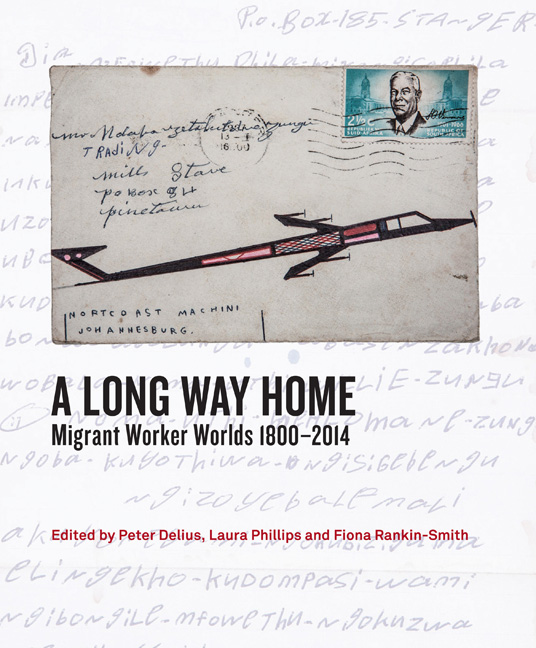

- Chapter 13 ‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu's Envelopes

- Chapter 14 Sophie and the City: Womanhood, Labour and Migrancy

- Chapter 15 Bungityala

- Chapter 16 Migrants: Vanguard of the Worker's Struggles?

- Chapter 17 Debt or Savings? Of Migrants, Mines and Money

- Chapter 18 Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Index

Chapter 8 - ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 July 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Highlighting Migrant Humanity

- Chapter 1 Ngezinyawo - Migrant Journeys

- Chapter 2 Slavery, Indenture and Migrant Labour: Maritime Immigration from Mozambique to the Cape, c.1780–1880

- Chapter 3 Walking 2 000 Kilometres to Work and Back: The Wandering Bassuto by Carl Richter

- Chapter 4 A Century of Migrancy from Mpondoland

- Chapter 5 The Migrant Kings of Zululand

- Chapter 6 The Art of Those Left Behind: Women, Beadwork and Bodies

- Chapter 7 The Illusion of Safety: Migrant Labour and Occupational Disease on South Africa's Gold Mines

- Chapter 8 ‘The Chinese Experiment’: Images from the Expansion of South Africas ‘Labour Empire’

- Chapter 9 ‘Stray Boys’: The Kruger National Park and Migrant Labour

- Chapter 10 Surviving Drought: Migrancy and the Homestead Economy

- Chapter 11 Migrants from Zebediela and Shifting Identities on the Rand, 1930s–1970s

- Chapter 12 Verwoerd's Oxen: Performing Labour Migrancy in Southern Africa

- Chapter 13 ‘Give My Regards to Everyone at Home Including Those I No Longer Remember’: The Journey of Tito Zungu's Envelopes

- Chapter 14 Sophie and the City: Womanhood, Labour and Migrancy

- Chapter 15 Bungityala

- Chapter 16 Migrants: Vanguard of the Worker's Struggles?

- Chapter 17 Debt or Savings? Of Migrants, Mines and Money

- Chapter 18 Post-Apartheid Migrancy and the Life of a Pondo Mineworker

- Notes on Contributors

- List of Figures and Tables

- Index

Summary

Days before the Forum on China-Africa Co-operation in Beijing in July 2012, the Mail & Guardian carried a story about a ‘new form of colonialism’. Warning readers about labour law violations and the exploitation of Africa's resources, author Paula Akugizibwe noted: ‘The boom of China in Africa is proving to be one of the most striking developments of twenty-first-century geopolitics’. But what the article did not say – and what has been largely forgotten in the South African imagination – is that there were equally dramatic headlines about the Chinese in South Africa slightly more than 100 years before. In the first years of the twentieth century, however, they signalled the geopolitics of an expanding British-South Africa ‘labour empire,’ as the SS Tweeddale docked at Port Natal (Durban) in July 1904, with a shipload of contracted Chinese labourers destined for the gold mines of the Transvaal.

The sudden influx of Chinese labour in 1904 was the beginning of a six-year ‘experiment’ in saving the white mining industry's cheap labour economy. As lowwage black labour from South Africa and Portuguese East Africa became less reliable and gold production levels dropped, mine-owners looked to China, where drought, floods and the Boxer Rebellion had driven unemployment rates to unprecedented levels. With the new Milner government's support for the mining industry, the Chamber of Mines capitalised on British networks and administration in China to set up a vast system to import Chinese labour.

Chinese men who were successfully recruited arrived into a world that was racist, violent and exploitative. The very ordinance that legislated their recruitment outlined a range of restrictive employment conditions. These included preventing Chinese miners from leaving the compound without a permit and for more than 48 hours; the exclusion of Chinese labourers from all skilled work and an absolute restriction on trading or owning any property. While sources from the Chinese miners themselves are quite limited, it is clear from the records of the Chamber of Mines that the conditions of employment were unbearable for many. Gary Kynoch quotes figures from the first four years of the Chinese mining presence, showing that there were ‘145 murders, 124 suicides, 28 state executions, 17 killed during the commission of “outrages” – crimes committed off mine premises – and 268 deaths directly related to opium use’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Long Way HomeMigrant Worker Worlds 1800–2014, pp. 116 - 131Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2014