During its long history, Persia has witnessed numerous invasions. But each time, it took revenge on its assailants, who were generally from Central Asia, by turning them into Iranians through a culture of assimilation. In 1722, the army of the ruler of Qandahār, once again from the East, took Isfahan and brought an end to the ruling Safavid dynasty. Persia thus became a battlefield between dynasties that were unable to permanently establish themselves. This continued until the end of the eighteenth century, when the Qajars were finally able to take power. It is to this period that we now turn in order to understand the difficult relationship between Shiism and politics and how a conventional monarchy was able to give birth to an Islamic republic. It was also at this time that the European empires began to take an interest in Iran and to drag it into the modern world. Iranian historians today see the Qajar period as a time of confrontation between their country and Europe, with the concomitant humiliations and wounds that resulted from it.

The Qājār dynasty, descended from a tribe whose early traces in Iran date to the eleventh century, held the reins of power until 1925. Much like the Safavids, they were Turkmen and spoke Turkish: their ethnic group of about 10,000 people led a nomadic life in northern Iran when it conquered the principalities that had fought over the Iranian plateau after the death of Nāder Shāh (1747). The founder of the dynasty, Āqā Mohammad Khān (1742–97) had been kept prisoner during his youth in Shiraz by the Zands, rulers of southern Persia from 1750 to 1794. Following his castration, he dreamt of revenge and of reconstituting the Safavid kingdom. Once freed, he gathered the members of his clan and took power in 1786, establishing his capital in Tehran. From there he could easily move northwards through the passes open for much of the year, through which the caravans linking Tabriz to Mashhad passed. It took him another ten years or so to unite Persian territory. It was only after having conquered Georgia and having ravaged Tiflis that he accepted the title of Shāh (“king”). Shortly thereafter, in 1797, he was assassinated by a servant, whom he had condemned to death and whom he had imprudently released.

Āqā Mohammad Khān, although without offspring, had decreed the law of succession, according to which the crown prince had to be the son of a princess of Qajar blood. This law was respected, but the nomination of a successor was often a merciless battle, with the two main clans within the tribe fighting for supremacy: the Qavānlu, who were in authority, and the Davalu. Despite marriages between the two clans that in theory neutralized internecine fights, each succession weakened the dynasty by giving rise to rivalries and plots within the royal family. From 1828, it was the support of a foreign power – Russia – that determined the legitimacy of a succession. Moreover, the Qajars preferred to choose members of their own tribe as governors or important ministers. This blood relationship allowed them to control Iran for more than a century by assuring the political cohesion of the kingdom but had the effect of impeding the renewal of the elite.

A Vast Territory

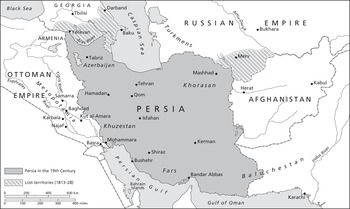

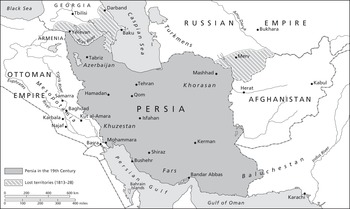

Toward 1800, the Persian kingdom extended over the Safavid territory, without Herāt to the east and the holy cities of Mesopotamia to the west. To the north, the founder of the Qajar kingdom had achieved the conquest of the Caucasus, with its rich arable land, where Iran delegated its sovereignty to Muslim and Christian vassals. The Caucasian provinces were not only a reservoir of slaves, soldiers, and concubines, they also formed a buffer zone against the threat of neighboring Ottomans and Russians.

In the south, in the Persian Gulf, the Safavids had evicted the Portuguese from Hormuz in 1622, with English help. Thereafter, thanks to the prosperity of the port of Bandar Abbās, Iranians dominated maritime trade. They also benefited from the port of Bushehr, which Nāder Shāh had developed to become the base of his fleet. Closer to Shiraz than Bandar Abbās, despite a mountainous barrier, it soon became the most important Iranian port. The British established themselves there in the mid-nineteenth century to put an end to piracy and ensure transport between Bombay and Mesopotamia. Iran claimed the Bahrain archipelago, home to an Arabic-speaking population but one which since Antiquity had also exhibited a strong Iranian influence; since early Islamic times most of the population was Shiite.

In Iran, a territory three times the size of France, it took weeks to travel from the capital to the cities in the periphery. In 1800, it had five or six million inhabitants. The population was scattered. Because of the desert climate of the Iranian plateau, villages were found at the bottom of the valleys, the only place – apart from the Caspian plain, which had abundant rains – where rural settlements could be established, as irrigation was ensured either on the surface or by draining and canalizing underground waters from the foothills. The model par excellence of this settlement was the garden, irrigated by cleverly arranged canals and protected against the dry wind by high mud walls.

The geographical and climatic environment had resulted in another peculiar form of land usage – nomadism. Benefiting in summer from pastures at higher altitudes freed from the snow, and in winter from the moderate temperature of the plains, the nomads of Iran did not have to make long seasonal migrations (on average 300 km or 190 miles). Their social structure was very hierarchized and tribal in nature, because the group had to defend its territory at any time against encroachment by rivals. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, it is estimated that Persia had half a million nomads, about 10 percent of the population. The nomadic population proportionally decreases with demographic growth, but numerically it remains almost constant and symbolically central. At present, it only represents a small proportion of the population.

Three centuries after the Safavids, it was a tribe of the same Turkmen group that held power: the Qajars themselves knew how to deal with the other tribes. The central Qajar government levied taxes on each head of livestock and allocated territories to the tribal groups, sometimes by moving entire tribes in accordance with the needs of land occupation and border surveillance. Nomadism and sedentary agriculture had gone hand in hand in Iran for centuries. In this semi-desert territory, the inevitable conflicts between settled populations and nomads were infrequent, especially since the two produced complementary goods that they could barter (meat, dairy produce, skins, and wool for wheat, fruit, and artisanal products).

The attraction of seasonal migration, like the attachment to gardens, remained essential elements of Iranian psychology until the end of the twentieth century. Yet with widespread urbanization, cohabitation in large settlements and worker migration, sometimes abroad, the ancient dreams of liberty and of solidarity that involved these two ways of life were shattered. The frustrations that modern Iranians have felt as a result of this uprooting undoubtedly explain in part the success of contemporary political preachers, who have brought back the utopia of solidarity and paradisiacal freedom to a society where one could see only walls and grievous displacement.

Between Heaven and Earth

Shiite Islam

Persia became Shiite in 1501. The first Safavid ruler imposed this form of Islam on his subjects, most of whom, although initially unfamiliar with its traditions, gradually adopted the new faith. The Safavids – falsely – claimed to be descended from the Imams and the Prophet and thus embodied religious legitimacy. According to Imamite Shiism, the legitimate authority belongs to the twelve Imams, descendants of the Prophet Mohammad via his daughter Fatima. Only the first Imam, Ali, was caliph; the others were set aside and, according to the Shiites, were martyred by the majority Sunnis. The twelfth Imam, also called the ‘hidden Imam,’ is believed to be still alive, although in occultation from the eyes of man. He rules the world in an invisible manner and will only reappear at the end of time to install a reign of justice and truth. His authority is “usurped” by all human government. Shiites have sought the most diverse theological and political solutions to overcome this obstacle. Commonly, the Safavids held the secular power in the name of the Imam and as delegates of theologians who were installed as official interpreters of religious legitimacy.

From the sixteenth century, Iranian culture was impregnated with the devotion of the Imams, either by pilgrimages to Mashhad, Qom, and the holy cities in Mesopotamia or by mourning ceremonies for the Imams. On the day of Āshurā, the tenth of the month of Moharram, Shiites commemorate the martyrdom of Hoseyn, the grandson of the prophet, the third Imam, at the battle of Karbalā in 680, during which he was killed by the army of the Ummayad caliph. During this month, and above all during the first ten days, the clergy commemorate the sufferings of the Imam by special sermons; the faithful weep and cry to show their sharing in the savior’s sacrifice. In addition to these sermons, there are performances of religious theater, played by lay actors.

During the Qajar period, these mourning representations (ta’ziye) became increasingly grandiose. They were patronized by the Shah or a magnate and sometimes performed with splendor in a public enclosure.Footnote 1 Even now, they are accompanied by processions of flagellants, grouped by guild or by quarter, who go through the streets whipping themselves with metal-tipped whips, while reciting and chanting lamentations that are taken over by the flagellants and the public. The most impassioned participants strike themselves with a sword so that their bloody heads add a touch of realism to the martyrdom of the savior. By associating themselves with the suffering of Hoseyn and his army, who were massacred at Karbala by the political authorities, the flagellants symbolically damn the despot and participate in a venture of salvation. Some Shiite reformers at the end of the twentieth century (Shariati) criticized this expression of grief and its promotion of suffering as it deadened the revolutionary spirit. In the 1960s, a radical interpretation came into being which sought to give the commemoration of the martyrdom of the Imams a revolutionary spirit, that of sacrifice for the sake of justice. The Shiite clerics, who fear outbursts, rarely encourage these ostentatious manifestations.

Since the time of the Safavids, the ulama have been divided into two camps, Akhbāri and Osuli, each having opposing conceptions of the interpretation of tradition (sunna) and of the role to play in relation to civil power. The Akhbāri-s adhere to the traditions established by the Imams during the first centuries of Islam. For them, each believer must find the Imam who will guide him to salvation, and this is achieved by learning Arabic and studying the teachings of the Imams. In the meantime, the believer continues to practice his religion in accordance with the teachings of tradition and avoids any practice that results in acknowledging a master other than the hidden Imam. In particular, he has to refuse participating in the Friday prayer or in a holy war, deeds that only may be undertaken under the direction of an Imam. Contrariwise, the Osulis maintain that their most learned ulama, the mojtahed-s, have full legitimacy to teach and discuss the principles of faith (osul), and, consequently, to reinterpret tradition, because they engage in scholarship in the name of the hidden Imam. They maintain that non-mojtahed Muslims have to “imitate” the mojtahed-s by applying the religious precepts as defined by them. This idea of “imitation” had to result, in the mid-nineteenth century, in the definition of a “source to imitate” (marja-e taqlid), who in some way is the interpreter of the will of the hidden Imam to the believers.

Religion and Political Legitimacy

At the end of the seventeenth century, several great ulama of Qom, in particular Mohsen Feyz, had developed Akhbāri tendencies in reaction to the excessive power the official Osuli ulama had assumed under the Safavids. The influence of the Akhbāris increased in Najaf, which had become a center of their school in the eighteenth century. But a dogmatic theologian, Mohammad Bāqer Behbahāni (1705–93) soon cursed them and chased them from the holy places in Mesopotamia.

The religious question acquired new impetus under the Qajars. Unlike the Safavids, the Qajars claimed neither descent from the Imams nor part of their heritage. Although protectors of Shiism, they had to negotiate with the ulama to have their legitimacy acknowledged. The Shiite clergy had suffered ordeals during the collapse of the Safavid kingdom: humiliation and persecution by the Sunni Afghan rulers and, subsequently, confiscation of their numerous endowments by Nāder Shāh and an attempt to drown their doctrinal idiosyncrasies in a syncretism which this monarch saw above all as a means to subdue the Shiite clergy. On several occasions, Nāder Shāh brought the ulama together and demanded that they redefine Shiism as a fifth religious school of jurisprudence (mazhab), at the same level as the four religious schools recognized by the Sunnis. Most Shiite theologians refused this compromise, which was imposed on them by force and which meant that they would have to stop cursing the Sunnis.

In 1848, a theoretical work aimed at the political education of Nāser od-Din Mirzā, who was to become Shah, gives this definition of the relations between the political power and authority of the ulama:Footnote 2

Royalty and Prophethood are two gems that are found mounted in the same setting. The Imamate and the government are two twins that are born from the same belly … One owes obedience to the just sovereign, because he is the Shadow of God on earth. Likewise, the conduct of political affairs is the younger brother of the Velāyat [a term that generally refers to the Imams in a Shiite context, both spiritual love and temporal authority] and the latter is the highest degree of humanity.

Thus, the Qajar monarch, like the mojtahed, has the right to interpret faith, based on reason, and to distinguish good from bad in the different political domains, whether it concerns military, economic, or social affairs. “Therefore, the monarch has the right to intervene [in the affairs of this world] and to interpret [the religious traditions], while the mojtahed does not have the right to govern.” This right, which fully belongs to the Imams, was not devolved to the ulama.

Nevertheless, after 1813, the doctrine of clerical power was affirmed by Mollā Ahmad Narāqi (1771–1829). This theologian for the first time defined a concept that Khomeyni borrowed one and a half centuries later, turning it into the lynchpin of his theory of “the authority of the theologian” (velāyat-e faqih). But Narāqi did not give this principle the importance which it acquired in the Islamic Republic. For Narāqi, authority was not only the prerogative of the Prophet and the Imams, it also belonged to those whom God appoints by their intermediary. While trying to define as closely as possible the power of the jurisprudents of religious law (foqahā), he distinguished several types of authority: political, judicial, administrative, but also the authority or mandate relating to orphans and the insane. While awaiting the return of the hidden Imam, in his view, the ulama are the real rulers, the only ones capable of legitimizing political action.

Some modern commentators point out that Narāqi wrote his tract during the first war between Persia and Russia (1804–13), at the moment when the ulama were calling for a holy war and needed to legitimize their political authority, but that he himself did not include the government in the tasks devolved to the jurisprudents, even though he had given a hint of being a possible intractable rival of public power; for example, on several occasions he sent back from Kāshān a governor appointed by Fath-Ali Shāh because he had acted unjustly. His most famous student, Mortazā Ansāri (1799–1864) played a major role in strengthening clerical authority, while adopting a clear position in favor of the withdrawal of the competence of the ulama in the judicial sphere.

After having been chased out of Karbalā, the Akhbāri ulama resurfaced in the Qajar period, but under the name Sheykhi and with a more speculative doctrine. Being less preoccupied with the legal status of the ulama while waiting for the return of the hidden Imam than with the presence of the Imam in this world and his way of revelation, the Sheykhis tried to restore the esoteric dimension of Shiism that the political victory of the Safavids had stifled. The founder of this school, Sheykh Ahmad Ahsā’i (1753–1826), was born in Bahrain and during his youth had experienced visionary states. Encouraged to attend the court of Fath-Ali Shāh he introduced a more ambiguous doctrine, one that was able to accommodate the mystical fervor of this monarch. He developed the already ancient idea of an intermediary region, situated somewhere between the spiritual and the material world, which he named Hurqalyā, where the Imam resided in occultation and where the resurrection would take place. Rejecting the teachings of the Osuli school, the Sheykhi-s moved closer to the very individualized practice of the Akhbāri school. But the majority of Shiites rejected several of their beliefs; for example, they refused the idea that in each era there is a single Imam, who speaks on behalf of God and the Prophet, or that the “perfect Shiites” are, in each era, secretly, the representatives or “the Gate” of the twelfth Imam. But Sheykhis themselves would reply that he who claims to be invested with this esoteric dignity violates the very principle of the eschatological expectation of the return of the Imam.

Bābism and Sufism

The Sheykhi school might have been able to survive discreetly if, in Karbalā, had not developed a teaching intensifying the eschatological expectation of the Imam and had not an enthusiastic disciple emerged, Ali-Mohammad Shirāzi (1819–50). The latter, believing himself to be the “Gate” (Bāb) leading to the Imam, soon claimed, by posing as the Imam himself, the abolition of the Koranic revelation to the benefit of his new message.

One cannot understand the emergence and the success of this religious movement, Bābism, without referring to the millenarian beliefs that flourished in Iran during the 1840s.Footnote 3 The major political catastrophes that had preceded the establishment of the Qajar dynasty had not been forgotten. The defeat that the Persian army suffered in the Caucasus against the Christian Russians presaged imminent cataclysm. Those who sought to benefit by announcing these misfortunes reminded the public that the occultation of the twelfth Imam had begun in 260 of the Hegira (874) and that his return would be one thousand lunar years later, in 1260 of the Hegira (1844). The buoyant return of Sufism in Iran only increased that feverous anxiety. Other causes, social and political, contributed to the success of the Bābis, which triggered a very violent reaction from the ulama and which was severely suppressed by the monarchy. This trauma weighed on Iranian politics for more than half a century.

Sufism, the mystical tradition of Islam that acquired institutional form beyond the mosques, has profoundly influenced Persian literature, notably lyrical and narrative poetry. The Safavids, who themselves emerged from a Sunni mystical order that became Shiite, had different attitudes toward Sufism. To establish their power in the name of Shiite Islam they had to rely on Shiite jurisprudents and theologians who already were clandestinely in Iran or came from present-day Syria or Bahrain to serve them. Thus, official Shiism was very much closed against Sufism, even more than were the Sunnis. By its peculiar religious practice, often critical of official doctrine, and by its devotion to a succession of mystical witnesses eventually leading to a “Pole” (qotb) – that is a living spiritual leader – Sufism sometimes appears to be a carbon copy of Shiism. It claims to be a spiritual derivation that goes back to the Imams.

The introduction of Sufism within Shiite Islam took multiple forms: concrete forms through the intermediary of mystical orders that developed above all after the eighteenth century, but also philosophical forms with mystical speculation, in which the Shiite philosophers – whom Henry Corbin called ‘theosophers’ – of the Safavid period excelled. The Sufis claimed to be the representatives of erfān (mysticism, gnosis), an ambiguous term that classical theologians readily accepted, unlike the term tasavvof (Sufism), which implied allegiance to a spiritual leader and to a brotherhood. The discourse of Shiite philosophers consisted in saying that knowledge of God is generally accessible through prophetic revelation, but that some have access to it in a more direct way via mysticism. Eventually, Koranic revelation and mystical knowledge merged, the latter able to annul the obligatory rituals to which orthodoxy clings. Moreover, the references to the great classics of Sunni Sufism, notably to the mystical martyr al-Hallāj and the thoughts of Ibn al-Arabi are identical in Shiite Sufism, even if they are interpreted differently.

The Shiite Sufis did not belong to the great Sunni mystical orders that had flourished before the Safavids, in the Persian language and on Iranian soil, such as the Naqshbandiye or the Qāderiye. But three major Shiite orders have flourished since then, the Zahabi, the Ne’matollāhi, and the Khāksār. The most important in terms of number of followers and branches, the Ne’matollāhi order, bears the name of the Sunni saint Shāh Ne’matollāh Vali, who died in 1431 and is buried in Māhān, near Kermān. At first, the order developed in India, in the Deccan, and it was only in the eighteenth century that one of its missionaries, Ma’sum-Ali Shāh Dekkani, began preaching in central Iran, in Shiraz, Isfahan, Hamadan, and Kerman. He was executed in Kermanshah on the orders of the mojtahed Mohammad-Ali Behbahāni, surnamed the “killer of Sufis” (sufi-kosh). The immediate disciple of this Sufi martyr, Nur-Ali Shāh Esfahāni, a prolific poet, was also poisoned by order of the “killer of Sufis.” After the latter’s death, the Sufis of this order avoided provocative statements and attitudes and enjoyed some respite. They even gained a disciple and soon protector, the third Qajar monarch, Mohammad Shāh (r. 1834–48), who choose as chancellor his Sufi master, Mirzā Āqāsi. This swing of Sufism toward power must have deeply irritated the ulama.

Neighbors and the Avidity of Foreign Powers

Far from the Mediterranean, cut off from other Muslim Mediterranean and Asian powers by its religion, Persia could have lived in peace, tormented only by the internal conflicts of dervishes and the expectation of the twelfth Imam. However, even at the beginning of the nineteenth century, this ancient land was already caught up in the conflicts of the colonial era. In fact, the Iranians represented an increasing challenge; they threatened Ottoman rule in Mesopotamia and hindered Russian advances in the Caucasus. They were also on the land route that led from Europe to India, but the colonial designs of France and Great Britain set Iran apart, as too distant and too large, turning instead toward north Africa and the Near East.

The Ottomans

The historical rivalry between the Persian and Turkish kingdoms had a religious justification. The Ottomans were the traditional defenders of orthodox Sunnism, the Persians, after 1501, of Shiism. Since the sixteenth century, the two sides had worn themselves out in a series of wars, until in 1639 a border compromise was found, roughly the actual western border of Iran, even though the claim to Mesopotamia continued on both sides. After having ruled, under the Safavids, for a few years (1622–38), over the Shiite holy places – a historical return to the sites where pre-Islamic Iran had its capital – in the eighteenth century, Iran twice tried in vain to conquer all or part of Mesopotamia, first under Nāder Shāh in the 1730s and later under Karim Khān Zand in 1775–79. These attempts to conquer Mesopotamia were not driven by hostility toward the Arab Bedouins, but by the desire to control that rich region, the site of the tombs of several Imams through which passed one of the pilgrim routes to Mecca. The Shiites went on pilgrimage to the holy cities of Najaf, Karbalā, and Samarrā. The greatest Shiite ulama, often of Iranian origin, had established themselves there since the strengthening of the Osuli school, attracting young theologians who had just finished their studies. Under the paradoxical protection of the Ottomans, they were sheltered from political interference by Tehran during the entire nineteenth century and until the creation of Iraq by the British in 1920.

Under the Qajars, despite a relative peace between the two states, the holy places of Mesopotamia remained a sensitive point. The relations between the subjects of the Sultan and those of the Shah were far from cordial. Sometimes persecutions of Shiites in the Baghdad region resulted in Iranian mobilization, more ostentatious than threatening, while sometimes governors in the south mounted razzias in Turkish territory, west of the Shatt ol-Arab; at other times, Ottoman Kurds descended on Iranian valleys where they took advantage of the women and the harvest. The British, who usually took sides with the Ottomans, meanwhile forced the Iranians to show reserve. During the Crimean War (1853–56), Persia sided with Russia, more because of what it hoped to gain (in relation to its dispute over Herāt) than out of enmity for the Sublime Porte, which it did not attack.

M1 Persia in the nineteenth century

The river border that allowed commercial vessels to go to Basra was itself a sufficient challenge to give rise to skirmishes. Access to the Persian Gulf via the Shatt ol-Arab had always been of greater strategic importance for Arab Iraq, then under Ottoman rule, than for the Iranians, who benefited from a long coastline and important ports.

In 1838, the Ottomans took advantage of the long siege of Herāt, which kept the Persian troops busy, to attack the port of Mohammara (now Khorramshahr), which took away too much trade from Basra. Following the joint intervention of Russia and Great Britain, the Ottomans and Persians were forced to negotiate. The treaty, signed in Erzurum in 1847, contained the seed of a border conflict which remained unresolved until the beginning of the twenty-first century. It fixed the river border along the Shatt ol-Arab not in the middle of the river bed, or talweg, in accordance with the general rule of border rivers, but on the eastern bank, and consequently the right to navigation for Iranians was but a concession. The treaty recognized Iranian sovereignty over the Arab tribes on their side of the river, but that sovereignty was totally theoretical. In fact, the allegiance of the Banu Ka’b tribe, whose territory extended on both sides of the river, was fluctuating, being more an allegiance to their chief than to any state.Footnote 4 The southern Iranian province was then officially called Arabestān, “the land of the Arabs.” Under Rezā Shāh it became known once again by its ancient name, Khuzestān.

The Russians

The Russian empire, Persia’s big non-Muslim neighbor, was separated from Iran by the Caucasus, the Caspian Sea, and Central Asia. Since the reforms of Peter the Great and, above all, of Catherine II, Russia had become a threatening power. It was through this Russian window that Iranians imaged Europe: violent, dominating but oriented toward progress and reforms. For a long time, they were haunted by a document forged under Catherine II that was presented as Peter the Great’s testament. It stated:

We must progress as much as possible in the direction of Constantinople and India. He who can once get the possession of these points is the real ruler of the world. With this in view we must provoke constant quarrels at the one time with Turkey, at another with Persia. We must establish wharves and docks in the Euxine and by degrees make ourselves master of that sea, as well as the Baltic, which is a doubly important element in the success of our plan. We must hasten the downfall of Persia, push on to the Persian Gulf, if possible re-establish the ancient commercial ties with the Levant through Syria, and force our way into the Indies, which are the storehouses of the world. Once there, we can dispense with English gold.Footnote 5

The Russian advance to the south during the nineteenth century seems to concretize a strategic plan that threatened Persia. The Caucasus had been conquered in the eighteenth century by Peter the Great, whose troops even had pushed as far south as Gilan and Mazandaran. But Nāder Shāh, having established his rule over Persian territory, then put an end to the Czar’s control over Baku and Darband. The Iranian vassals of the Caucasus, such as Georgia and Armenia, two Christian nations, hesitated between putting themselves under Russian protection, whose Christian culture was more familiar to them, and Persian protection, which fiscally and politically was less threatening. Iran laid claim to these lands until 1921. In the Qajar period, the Russians moved people – willingly or unwillingly – to rechristianize the Caucasus. Around Erevan in particular they established villages of Armenians from Iranian Azerbaijan who were incited to leave their homes and their church with their livestock and their priest. The policy resulted in weakening Armenian Christians and Assyro-Chaldean communities who remained in Persia. It also shrank the space of Armenian culture; historically Greater Armenia had encompassed part of Anatolia and also Azerbaijan.

Moreover, the Russians used all means available to them to export their goods to Iran: textiles, metals, and sugar. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, when coffee was still the most popular beverage, Iranians gradually adopted the Russian way of preparing tea with samovars using charcoal and drank from small glasses placed on a deep saucer, which the Iranians continue to practice to this day.Footnote 6

The French and English

Russian designs clashed with other conflicts that arose in Persia itself between the French and the English. Fath-Ali Shāh, who succeeded the founder of the Qajar dynasty in 1797, sought an alliance to retake Georgia, which Czar Paul I had just annexed. At that time, the French Emperor Napoléon wanted to ally himself with Persia to weaken the Russians but, above all, to be able to get land access to India. This dream, born during his legendary Egyptian adventure, would allow him to take revenge on the British, who were already established in Bengal and Bombay.

From their side, the British hoped to make Persia the shield of their Indian empire. In 1800, to impress Fath-Ali Shāh and to offer him military and financial assistance, the East India Company sent captain John Malcolm on an embassy with valuable presents. It had no great effect, because the Iranian monarch understood them to be a tribute brought to him as a sign of submission. But the British changed their position when the possibility of action by the Persian army in the Caucasus became a real prospect, Russia being their ally against France. Malcolm had not yet left Persia when his trusted interlocutor, grand vizier Ebrāhim Kalāntar Shirāzi, a survivor of the Zand regime, was accused of treason, had his eyes pulled out, his tongue cut out and was executed some months later. Kalāntar had seen an alliance with the British as a possible support for his dream of a federation of cities and tribes of the south, and a counter-weight to the unification of Persia of which he had been an efficacious agent.

Napoléon had a message taken to the Shah by Commander Romieu and Amédée Jaubert, who were sent as envoys in May 1805. The Shah replied that he himself had already considered an alliance with France and that he proposed to start hostilities with Russia as soon as possible. France and Russia’s alliance had not yet down, which happened in September 1805. Two years later France signed a treaty with Iran at Finkenstein in which it committed itself to place its forces at the service of its ally to regain Georgia; in return, Persia had to evict the British instructors from its army and replace them with Frenchmen. The new envoy of the emperor, his aide-de-camp general Gardane, had also prepared the passage of a French army of 20,000 men, to which about 12,000 Persian soldiers were to be added, trained by French officers and armed with French rifles and cannons founded in Isfahan.

However, shortly thereafter, on 7 July, Napoléon signed the treaty of Tilsit with Russia. In this new and fragile alliance, he was more concerned to widen the anti-British coalition than to help Persia. One may assume that the Czar, if his French ally had put pressure on him, would have withdrawn from Georgia without a fight. In Tehran, the French ambassador desperately tried to convince the Shah that France was doing its best. As one might expect, the Russo-Persian negotiations in Tehran about Georgia led to nothing. The Russians, seeing Napoléon’s difficulties in Spain, were somewhat skeptical about the help the French were going to extend to Persia. They took advantage of the situation by trying to retake Erevan, the Armenian capital, but were met by Persian resistance (October 1808). Despite the Shah’s request, the French refused to intervene against their Russian ally.

Gardane was still in Tehran when John Malcolm, who again had been sent by the East India Company, arrived with great pomp via the Persian Gulf, but he was stopped at Shiraz in May 1808, because the Shah refused to receive him at Tehran in the hope that the French alliance would be reactivated. Piqued, Malcolm returned to Calcutta, disavowed by London. Finally, Fath Ali-Shāh decided to dismiss the French and to receive a British delegation. The British were starting to feel the backlash of their colonial grandeur, and the Indian administrators clashed with the policy agreed in London. The new British envoy was Sir Harford Jones, a man who knew Persia very well and who was at that time based in Baghdad. In 1809, Jones concluded the first alliance between Great Britain and Iran. In retaliation, the governor of Bombay refused to meet the costs of this mission.

Jones’ success signaled the end of French hopes in Persia, apart from military assistance, because the governor of Tabriz, Crown Prince Abbās Mirzā, employed former officers of the Napoleonic army – soldiers of fortune – to modernize the Persian army. The latter benefited from the assistance of the two enemy powers, whose relations with the Russian enemy were constantly changing.

Napoléon rode roughshod over the Finkenstein commitments only a few months after the treaty was signed, and without even warning the Persian side, thus demonstrating the impotency of the Qajar dynasty in the face of external conflicts. But part of the Qajars’ reservations in respect of France derived from the French Revolution. The echoes of the republic that had begun with the beheading of a king did not inspire them with great confidence, and the English found it easy to exaggerate the horrors of the Revolution. In contrast, Napoléon’s military exploits inspired real sympathy, above all his coronation in 1804 and his campaigns against the Russians, whose threat was directly felt as far as Tehran. Subsequently, when the British themselves turned into cumbersome and arrogant allies, the symbol of that populist emperor, who for such a long time had kept them in suspense, represented an even more attractive model, and the biographies of the emperor were translated into Persian.

The confrontation of Persia with the European nations was also challenging for the Persian envoys. Noting the indisputable superiority of the western powers and fascinated by an open society aiming at progress, some of them turned to Masonic lodges. From the beginning of the nineteenth century, Persia was involved in imperial conflicts without mastering the military and political instruments that would have allowed it to defend its integrity. To overcome this heavy handicap the Qajar monarchs started to fight in a different manner.