Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Networks of Solidarity: D.D.T. Jabavu’s Voyage to India

- Revisiting D.D.T. Jabavu, 1885–1959

- Notes on the Original and the Translation

- In Praise of Cecil Wele Manona, 1937–2013

- E-Indiya nase East Africa

- In India and East Africa

- Afterword: Jabavu and African Translations for the Future

- References

- Editors’ Biographies

- Index

Revisiting D.D.T. Jabavu, 1885–1959

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 March 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Networks of Solidarity: D.D.T. Jabavu’s Voyage to India

- Revisiting D.D.T. Jabavu, 1885–1959

- Notes on the Original and the Translation

- In Praise of Cecil Wele Manona, 1937–2013

- E-Indiya nase East Africa

- In India and East Africa

- Afterword: Jabavu and African Translations for the Future

- References

- Editors’ Biographies

- Index

Summary

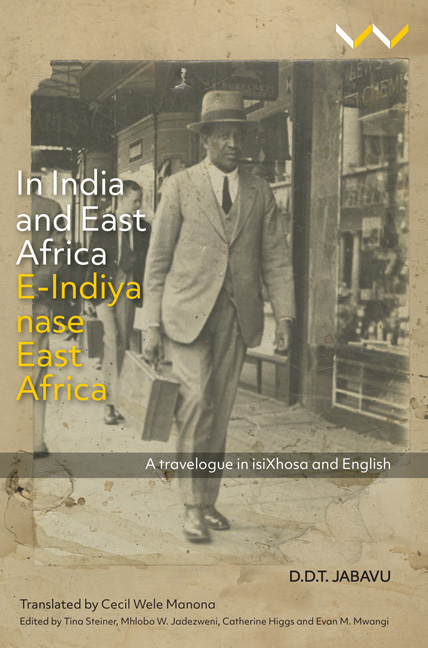

Lovedale Press, in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa, published E-Indiya nase East Africa (In India and East Africa) for Professor Davidson Don Tengo (D.D.T.) Jabavu in 1951. It was one of his last substantial publications and fittingly, in a life filled with travel, it was a travelogue, a narrative of his visit to India in late 1949 and then to Kenya and Uganda, both still part of the British Empire. In 1951, Jabavu was 66 years old. That same year, his wife of 35 years, Florence Tandiswa Makiwane, died. This personal loss took place in the context of momentous change in South Africa. In April 1951, speaking to graduating students at the South African Native College at Fort Hare, where he had spent his career as a professor of Latin and African languages, Jabavu lamented the impact of the introduction of apartheid following the victory of the National Party in 1948. Fort Hare (as the college was popularly known) was founded in 1916 as a university for black Africans from South Africa and across the continent. It had been a grand experiment: ‘a microcosmic cross-section of educational South Africa, and also of the great world of modern Civilisation … a centre around which all the colour groups of the South African population meet at a high level of education’. Apartheid South Africa had crushed that vision, and was proving ‘particularly hostile to what it calls the “Fort Hare product”’. In 1951, Jabavu urged students to embrace Mahatma Gandhi as a role model for how to best serve their communities, and to use their ‘higher education for [the] uplift … [of] less privileged groups’. This appeal echoed the vision which had shaped Jabavu's youthful hopes for what South Africa might become, even if, in 1951, that vision seemed unlikely to come to fruition.

D.D.T. Jabavu was born in October 1885, in what was then the British Cape Colony, into a family that exemplified the ‘missionaries’ axiom, that to be Christian was to be civilized, and to be civilized was to be Christian’. He was the eldest of six children. Both of his parents had grown up in Christian households. His mother, Elda Sakuba Jabavu, was the daughter of the Reverend James B. Sakuba, a Wesleyan Methodist minister. His father, John Tengo Jabavu, was the editor of the Xhosa–English newspaper Imvo Zabantsundu (African Opinion).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- In India and East Africa / E-Indiya Nase East AfricaA Travelogue in isiXhosa and English, pp. 27 - 42Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2019