Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Networks of Solidarity: D.D.T. Jabavu’s Voyage to India

- Revisiting D.D.T. Jabavu, 1885–1959

- Notes on the Original and the Translation

- In Praise of Cecil Wele Manona, 1937–2013

- E-Indiya nase East Africa

- In India and East Africa

- Afterword: Jabavu and African Translations for the Future

- References

- Editors’ Biographies

- Index

Afterword: Jabavu and African Translations for the Future

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 March 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Networks of Solidarity: D.D.T. Jabavu’s Voyage to India

- Revisiting D.D.T. Jabavu, 1885–1959

- Notes on the Original and the Translation

- In Praise of Cecil Wele Manona, 1937–2013

- E-Indiya nase East Africa

- In India and East Africa

- Afterword: Jabavu and African Translations for the Future

- References

- Editors’ Biographies

- Index

Summary

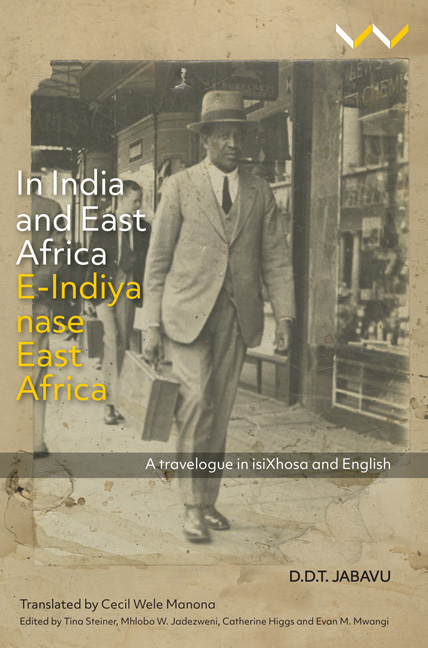

Davidson Don Tengo ‘D.D.T.’ Jabavu is a household name in African studies and black anti-colonialism, but he was for me, until recently, one of those figures you faintly knew about from distant readings of their works as cited by other people. That is, I had little incentive to read him as a primary subject to engage with. I got some interest in the South African writer when preparing for a class in Indian Ocean studies, a field of cultural studies I was still quite sceptical about, when I first heard about his 1951 isiXhosa-language E-Indiya nase East Africa, a travelogue about his journey from South Africa, through East Africa, to India for the 1949 World Pacifist Conference. I regarded Jabavu as part of a liberal humanist cadre backpedalling the full-throated opposition to white supremacism; he seemed not to espouse the kind of anti-racism I have come to admire in such revolutionaries as Steve Biko. But after reading Cecil Wele Manona's translation of this book, I think it would be fruitful to put Jabavu in the context of his time and appreciate what he offers in restoring black bodies dehumanised through slavery and minority white rule in South Africa. We should restore his legacy as a pioneer African writer, politician and translator. In seeking this recuperation, I am encouraged by South African thinkers like Xolela Mangcu, who has included Jabavu among the ‘heroes’ whose ‘memories must rise from the grave’. In reading him in the context of African Indian Ocean studies, Jabavu offers an example of what epistemological breaks from dominant modes of critical theorising should look like in the future.

Even as he reaches out to other cultures, some of which probably do not respect his, Jabavu ensures in E-Indiya nase East Africa that black voices are not silenced in the way he represents and translates them. This is something we should emulate because in the neoliberal academy, literary and translation studies focusing on the Indian Ocean can easily become just another site of anti-blackness, where scholars from predominantly white institutions devise projects, generously funded by white foundations, that seek to marginalise black populations on the continent.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- In India and East Africa / E-Indiya Nase East AfricaA Travelogue in isiXhosa and English, pp. 279 - 286Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2019