Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Sources

- 1 Alternate possibilities and moral responsibility

- 2 Freedom of the will and the concept of a person

- 3 Coercion and moral responsibility

- 4 Three concepts of free action

- 5 Identification and externality

- 6 The problem of action

- 7 The importance of what we care about

- 8 What we are morally responsible for

- 9 Necessity and desire

- 10 On bullshit

- 11 Equality as a moral ideal

- 12 Identification and wholeheartedness

- 13 Rationality and the unthinkable

12 - Identification and wholeheartedness

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2012

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Sources

- 1 Alternate possibilities and moral responsibility

- 2 Freedom of the will and the concept of a person

- 3 Coercion and moral responsibility

- 4 Three concepts of free action

- 5 Identification and externality

- 6 The problem of action

- 7 The importance of what we care about

- 8 What we are morally responsible for

- 9 Necessity and desire

- 10 On bullshit

- 11 Equality as a moral ideal

- 12 Identification and wholeheartedness

- 13 Rationality and the unthinkable

Summary

The phrase “the mind-body problem” is so crisp, and its role in philosophical discourse is so well established, that to oppose its use would simply be foolish. Nonetheless, the usage is rather anachronistic. The familiar problem to which the phrase refers concerns the relationship between a creature's body and the fact that the creature is conscious. A more appropriate name would be, accordingly, “the consciousness-body problem.” For it is no longer plausible to equate the realm of conscious phenomena – as Descartes did – with the realm of mind. This is not only because psychoanalysis has made the notion of unconscious feelings and thoughts compelling. Other leading psychological theories have also found it useful to construe the distinction between the mental and the nonmental as being far broader than that between situations in which consciousness is present and those in which it is not.

For example, both William James and Jean Piaget are inclined to regard mentality as a feature of all living things. James takes the presence of mentality to be essentially a matter of intelligent or goal-directed behavior, which he opposes to behavior that is only mechanical:

The pursuance of future ends and the choice of means for their attainment are the mark and criterion of the presence of mentality in a phenomenon. We all use this test to discriminate between an intelligent and a mechanical performance.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

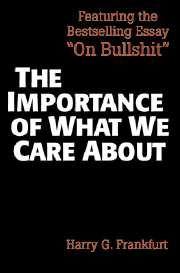

- The Importance of What We Care AboutPhilosophical Essays, pp. 159 - 176Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1988

- 75

- Cited by