Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- The Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Pre-Bard Stage Career of John Barrymore

- 2 Dangerously Modern: Shakespeare, Voice, and the “New Psychology” in John Barrymore's “Unstable” Characters

- 3 The Curious Case of Sherlock Holmes

- 4 John Barrymore's Introspective Performance in Beau Brummel

- 5 “Keep Back your Pity”: The Wounded Barrymore of The Sea Beast and Moby Dick

- 6 From Rome to Berlin: Barrymore as Romantic Lover

- 7 The Power of Stillness: John Barrymore's Performance in Svengali

- 8 Prospero Unbound: John Barrymore's Theatrical Transformations of Cinema Reality

- 9 A Star is Dead: Barrymore's Anti-Christian Metaperformance

- 10 Handling Time: The Passing of Tradition in A Bill of Divorcement

- 11 John Barrymore's Sparkling Topaze

- 12 “Planes, Motors, Schedules”: Night Flight and the Modernity of John Barrymore

- 13 Barrymore and the Scene of Acting: Gesture, Speech, and the Repression of Cinematic Performance

- 14 “I Never Thought I Should Sink So Low as to Become an Actor”: John Barrymore in Twentieth Century

- 15 Barrymore Does Barrymore: The Performing Self Triumphant in The Great Profile

- Works Cited

- Index

5 - “Keep Back your Pity”: The Wounded Barrymore of The Sea Beast and Moby Dick

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 June 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- The Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Pre-Bard Stage Career of John Barrymore

- 2 Dangerously Modern: Shakespeare, Voice, and the “New Psychology” in John Barrymore's “Unstable” Characters

- 3 The Curious Case of Sherlock Holmes

- 4 John Barrymore's Introspective Performance in Beau Brummel

- 5 “Keep Back your Pity”: The Wounded Barrymore of The Sea Beast and Moby Dick

- 6 From Rome to Berlin: Barrymore as Romantic Lover

- 7 The Power of Stillness: John Barrymore's Performance in Svengali

- 8 Prospero Unbound: John Barrymore's Theatrical Transformations of Cinema Reality

- 9 A Star is Dead: Barrymore's Anti-Christian Metaperformance

- 10 Handling Time: The Passing of Tradition in A Bill of Divorcement

- 11 John Barrymore's Sparkling Topaze

- 12 “Planes, Motors, Schedules”: Night Flight and the Modernity of John Barrymore

- 13 Barrymore and the Scene of Acting: Gesture, Speech, and the Repression of Cinematic Performance

- 14 “I Never Thought I Should Sink So Low as to Become an Actor”: John Barrymore in Twentieth Century

- 15 Barrymore Does Barrymore: The Performing Self Triumphant in The Great Profile

- Works Cited

- Index

Summary

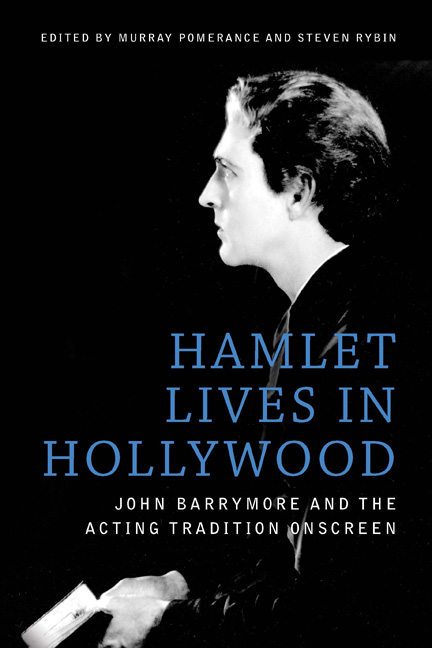

A performer noted for his striking beauty, John Barrymore was nevertheless familiar with contorting his appearance to attract equally the dreadful fascination of his viewers, having done so most remarkably playing the lead in John S. Robertson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1920). A similar transformation also characterizes his starring roles in dual adaptations of Moby-Dick: the silent production The Sea Beast (1926) and its sound remake Moby Dick (1930). Released amid the novel's critical reappraisal, yet prior to its accumulation of unsurpassed prestige in the American literary canon, both films renovate Melville's tale considerably for the screen, focusing on a romantic union thrown into crisis when one of the couple, young harpooner Ahab Ceeley (Barrymore), is wounded by the white whale during the course of the narrative. The metamorphosis of Barrymore's Ahab after his injury is most stunning in The Sea Beast: initially a sprightly young sailor, Ahab transforms into a haggard ghoul, with eyes both sunken and penetrating as he pursues his hated prey. The Ahab of Lloyd Bacon's later Moby Dick, while not quite the Gothic spectacle presented in The Sea Beast, still grimly snarls in marked contrast to the dashing man we see at the start of the film. In both films, the wounding of Ahab effects a deep reconfiguration of both his appearance and his character. The sailor eventually seeks retribution from the whale, yet it is his romantic rejection that lingers most centrally and spurs his vengeful quest. This chapter focuses on both of these roles and on the narratives that articulate and augment them, emphasizing Barrymore's Ahab as the possessor of a confident, desirable masculinity radically compromised by injury. Additionally, I suggest that these narratives of stigma and disability had particular resonance for the postwar period of the films’ production and reception in which numerous wounded men, formerly healthy and whole, struggled, with wounds anddisfigurements, to be reintegrated into society and the prevailing definitions of masculinity.

“MY DARLING! HOW HORRIBLE, HOW PITIFUL!” THE INJURED AHAB

Both The Sea Beast and Moby Dick institute any number of changes to gall Melville purists, and a series of modifications further distinguish one adaptation from the other. Nevertheless, both emphasize the stymied (and finally revived) union of sailor Ahab Ceeley and the daughter of a local preacher, in The Sea Beast Esther (Dolores Costello), renamed Faith (Joan Bennett) in Bacon's remake.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Hamlet Lives in HollywoodJohn Barrymore and the Acting Tradition Onscreen, pp. 59 - 70Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2017