Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 A Pianist Is Born

- 2 A Concert Pianist in Exile

- 3 Spirituality, Love, and Color: Understanding Messiaen’s Music

- 4 From Thaw to Frost: Neonationalism and the Messiaen Premieres in the USSR

- 5 Haimovsky and Grazhdanstvennost’

- Appendix 1 Selected Performances of the Music of Olivier Messiaen by Gregory Haimovsky, 1964–72

- Appendix 2 Selected Writing by Gregory Haimovsky on the Music of Olivier Messiaen

- Notes

- Index

4 - From Thaw to Frost: Neonationalism and the Messiaen Premieres in the USSR

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 June 2021

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 A Pianist Is Born

- 2 A Concert Pianist in Exile

- 3 Spirituality, Love, and Color: Understanding Messiaen’s Music

- 4 From Thaw to Frost: Neonationalism and the Messiaen Premieres in the USSR

- 5 Haimovsky and Grazhdanstvennost’

- Appendix 1 Selected Performances of the Music of Olivier Messiaen by Gregory Haimovsky, 1964–72

- Appendix 2 Selected Writing by Gregory Haimovsky on the Music of Olivier Messiaen

- Notes

- Index

Summary

The Deputy Minister of Culture [Vasiliy] Kukharsky hit the floor again and again with his cane (he was disabled from the war): “Chase, chase this Haimovsky from the Union of Composers and the magazine … chase him away along with his Messiaen!”

—Gregory Haimovsky, Olivier Messiaen in My LifeDuring the 1950s, many Russian intellectuals were aware and wary of a continuous cultural tension between the Soviet ideology of neonationalism and Western concepts of music, literature, and the other arts. The practical effects of this struggle affected daily life in Soviet conservatories, so much so that Haimovsky and his classmates—sometimes informed “quietly” by their professors—were familiar with aspects of the fight for and against the Communist doctrine of Socialist Realism.

However, when Haimovsky dared to spotlight Messiaen's works in the mid-1960s and early 1970s, he never imagined how forcefully the authorities would reject his initiatives. Case in point: the Soviet magazine Zhurnalist (Journalist) condemned Haimovsky for writing about Messiaen's music, a composer they deemed possessing “extremely suspicious aesthetical principles.” The roots of this condemnation trace back to Lenin's and Stalin's concepts of and policies about the values and roles of the arts in Soviet society, which Haimovsky did not understand at the time. More specifically, and unbeknownst to Haimovsky, the tumultuous history of communism's proand anti-Western stipulations about “acceptable” artistic creativity, and artists’ pro-and anti-Soviet attitudes, took countless twists and turns through complex layers of the nation's political, philosophical, and cultural domains.

In this chapter, I continue my discussion of Haimovsky's musical and literary championing of Messiaen's works and the emergence of his oeuvre in Soviet culture. Before doing so, however, it is important to outline several developments in Communist arts policies between 1917 and 1964 that presaged Haimovsky's clash with the Soviet authorities that attempted to block his efforts during the 1960s and 1970s.

Historical Matters

In 1917, Communist attitudes towards the arts paved the way for a significant degree of freedom and experimentation. Officials believed that artists had a social and political responsibility to create works with a discernable Soviet identity. They viewed the arts as potent revolutionary forces. The poet Vladimir Mayakovsky gave voice to this Cultural Revolution:

Beat the squares with the tramp of rebels!

… Now's the hour whose coming it dreads. (1917)

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

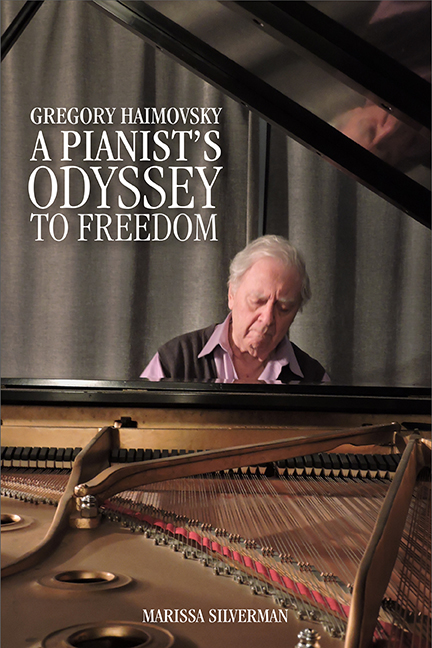

- Gregory HaimovskyA Pianist's Odyssey to Freedom, pp. 101 - 135Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2018