Campanian wall-painting has a complex history of framing, deframing and reframing. Since their discovery in the eighteenth century, many fractured fresco fragments have been excised from their original mural contexts: they have been hung in the museum like canvases in a gallery.Footnote 1 Copies of the most famous extracted mural panels (and sometimes also their associated ‘ornamental’ frameworks) were likewise soon commissioned by contemporary Grand Tourists, inserted into the frameworks of British aristocratic homes – from James ‘Athenian’ Stuart's painted room at Spencer House in London to Ickworth House's thoroughly more Victorian-looking ‘Pompeian Room’.Footnote 2 Modern photographs, not to mention textbooks, catalogues and websites, very much follow suit: by isolating the panelled ‘highlights’ of the wall from their mural surrounds, photographic reproductions necessarily distort, reconfiguring such images in both formal and conceptual ways.Footnote 3

As other contributors to the present book emphasise, Roman wall-paintings are by no means the only materials of Graeco-Roman art to have undergone this sort of physical and intellectual reframing. One might compare, for example, Clemente Marconi's comments about d'Hancarville's eighteenth-century representation of the ‘Hamilton Vase’, with its dismantling of the pot's original three-dimensional ‘objectness’ (and not least its addition of a containing ornamental border on all four flat sides) (Figures 2.1 and 2.2);Footnote 4 the courtyard of the Palazzo Mattei in Rome, as discussed by Verity Platt, provides a related parallel (Figure 7.1), this time incorporating Roman sarcophagi panels within an external palatial façade, thereby ‘flattening out’ the original, three-dimensional function of sarcophagi as containers for the dead.Footnote 5 Unlike the material discussed by both Marconi and Platt, our modern reframings of Pompeian wall-paintings do not comprise a medial sort of collapse: whether rehung on the wall, emulated within a Neoclassical aristocratic mansion, or reproduced on the page and screen, these two-dimensional forms remain two-dimensional. But such reframings – such literal and metaphorical removals of wall-paintings from their original mural and architectural frameworks – nonetheless impact upon how this material is viewed. If we tend to look at Campanian wall-paintings through the frames of their modern afterlives – and above all through the frames of post-Enlightenment art history – such frames are themselves framed by larger interpretive assumptions about the medium, mechanics and meanings of this material.

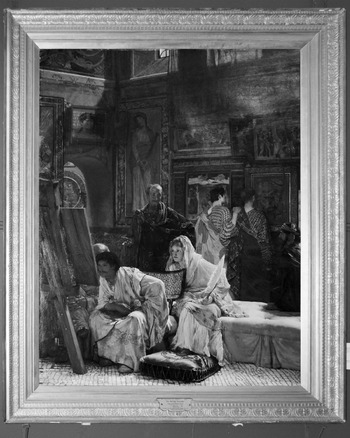

Figure 4.1 Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, A Picture Gallery (Opus CXXVI), 1874. Burnley, Towneley Hall Art Gallery and Museum.

Few images better visualise the significance of these frames than Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema's 1874 painting of an imagined Roman ‘picture-gallery’ (Figure 4.1).Footnote 6 As with a number of other pictures treating related subjects, Alma-Tadema's depicted ‘gallery’ incorporates some of the most celebrated images from Pompeii and Herculaneum.Footnote 7 On the far left can be seen the raised spears and single horse of one tableau (albeit almost entirely eclipsed by the surrounds of Alma-Tadema's own picture-frame), alluding to the so-called ‘Alexander Mosaic’ discovered in the Casa del Fauno in 1831 (Pompeii, VI.12.2). Just as in the Archaeological Museum at Naples, the image has been transferred from underfoot floor-mosaic to mural adornment, albeit now framed within a multi-tiered black, red and gold surround (complete with elaborate floral pattern).Footnote 8 To the right, on the rear wall, are two additional pictures deriving from images removed from Pompeii and Herculaneum. In these pictures we see Greek ‘masterpieces’ that were also mentioned by ancient writers: the large panel to the left of the rear wall shows a pensive-looking Medea (attributed to Timomachus); below it, to the right, is a smaller panel portraying Agamemnon's sacrifice of Iphigenia (attributed to Timanthes).Footnote 9

In all three cases, Alma-Tadema's reproduced images hark back to famous prototypes known from Campania. And yet, at least in this depicted gallery, all three pictures are also presented as independent panel-paintings, each contained within its own ornamentally bordered frames. What ultimately interested the artist are not the mural, domestic or cultural contexts that once surrounded these fragmented fresco images, in other words, but rather the information that they collectively bestow about a (largely lost) tradition of Greek panel-painting. Each picture-frame – whether a simple wooden casing, a geometric surround, or an elaborate floral border – acts out on a physical level the recurrent conceptual assumption that Campanian images can be extracted from their original surrounds. At the same time, each reframed example wilfully restores such Roman mural ‘copies’ to the status of ‘Old Master’ Greek ‘originals’, as conceived through the aestheticising frame of Alma-Tadema's own tableau.

Figure 4.2 View of the same picture, as displayed in the Towneley Hall Art Gallery and Museum in Burnley.

There is more to this act of reframing than physical boundaries alone. By transforming Campanian wall-paintings into the framed canvases of the modern art gallery, Alma-Tadema transforms them into ‘Art’ in its familiar, autonomous, post-Enlightenment sense.Footnote 10 Removed from their former mural settings, and inserted into the self-standing picture-frames of the museum, these paintings invite a gaze of quiet reflection and enthralled absorption; as such, the framed images within the painting resemble the gilded opus of Alma-Tadema's own canvas, as today displayed in its own ‘picture-gallery’ at Burnley's Towneley Hall (Figure 4.2).Footnote 11 Displaced and decontextualised, the extracted images inside the picture's frame become self-contained entities in their own aesthetic right: the represented frames of each imagined painting – in turn replicated in the frame of the representing picture – turn them into objects of contemplation. In the words of Louis Marin, the framing here ‘renders the work autonomous in visible space’; or as William Harries succinctly puts it, such frames may be ‘understood as objectifications of the aesthetic attitude’, thereby conferring an idea of the ‘autonomous aesthetic object’.Footnote 12 The frames enwrapping the pictures, in other words, are integral to the aesthetic enrapture made manifest within the frame of this self-declared opus.

The result, at least in the representational space of Alma-Tadema's painting, is a strikingly modern-looking ‘picture-gallery’, premised in turn on decidedly modern modes of looking. This explains the artistic fantasy that allows the artist to populate his gallery with modern-day Victorian dilettanti (complete with the recognisable portrait features of the artist's contemporaries).Footnote 13 It also explains the legends accompanying a number of the paintings (‘Marcus Ludius’ inscribed on the rear wall ‘landscape’, for example, and ‘[Pau]sias’ underneath the lower right ‘lion’).Footnote 14 The display strategies depicted within this allegedly Roman gallery have been configured after those of the Victorian museum, whereby each and every framed ‘master-piece’ is duly attributed (most often on its framed outer fringe) to its associated artist.Footnote 15

The aesthetic affordances of the frame are fundamental to Alma-Tadema's larger conceptual approach to Roman wall-painting: the physical (re)framing of these wall-paintings goes hand in hand with an ideological (re)framing of their function, value and meaning. On the one hand, Alma-Tadema's painting represents a sort of representational mise en abyme: just as our framed panel (surrounded by its ornate gilded edge) contains further framed paintings within it, so too are viewers of that panel invited to replicate the same aesthetic reflections that we see portrayed inside the frame. On the other hand, and despite all the recognisable ‘classics’ of ancient art, this recreative vision of a ‘Roman picture-gallery’ toys with an ‘invisible masterpiece’ lying beyond our view – the reversed-view picture-panel to which the three seated subjects look in enraptured turn, and which itself overlaps with the physical boundaries of Alma-Tadema's own image.Footnote 16

It is with such physical and ideological reframing of Campanian wall-painting that the present chapter is concerned. The rich and varied semantic significance of ‘decorative’ frameworks in Roman wall-painting has already been discussed in this volume's introduction (analysing the ‘self-aware’ frames in the Villa of Poppaea at Oplontis (Figure 1.19), the Villa della Farnesina at Rome (Figure 1.20) and the Casa del Bracciale d'Oro at Pompeii (Figure 1.22), for example). Where the introductions to both the volume and this current section have talked about framing in Roman frescoes tout court, however, my objective here is to focus on just one ‘genre’ of depicted subjects, grouped together under the habitual modern category of ‘still lifes’.Footnote 17 By exploring the ways in which Campanian ‘still-life’ images were incorporated within their original mural contexts, I set out to explore the larger disjunctions between ancient and modern modes of viewing them, rooted as they are in associated modes of physical and metaphorical framing.

My particular choice of case study is important. Our very delineation of these images as ‘still lifes’, as we shall see, returns us to the frames and frameworks of Alma-Tadema's painting. Of all modern artistic genres, the ‘still life’ epitomises a set of aestheticising ideas, ideals and ideologies: if Roman images of fruit and other comestible subjects have been assumed to function in the manner of a posthumous western tradition of still-life painting, they have also been viewed in ‘purely’ aesthetic terms, as though catering to a Kantian gaze of disinterested artistic reflection. Like the self-contained panels of Alma-Tadema's gallery, Campanian paintings of food have in one sense been deframed – isolated from their original cultural frameworks, no less than their original physical sounds. Yet in another literal and figurative sense, they have also been reframed: bounded within the cultural limits of a modern artistic genre, they have been understood as autonomous aesthetic entities, intended above all as self-standing objects of aesthetic reflection.

If my chapter exploits the affordances of the frame to showcase a number of differences between ancient and modern modes of viewing the ‘still life’, it also attempts to look beyond those modern interpretive frameworks, relating so-called ‘still lifes’ back to culturally contingent discourses about nature, realism and representation. As we shall see, the concept of framing is particularly germane here, since it captures an interest both in the physical incorporation of these images within mural schemes and in the metaphorical surrounds of their significance. By looking at how Campanian mural schemes literally framed these images, and at the associated ways in which their interpretation was figuratively framed within preconceived ideas about their comestible subjects, my aim is demonstrate how so-called ‘still-life’ images themselves framed, and were framed by, contemporary cultural debates about make-believe, simulation and illusion.

The Anachronistic Frame of the ‘Still Life’

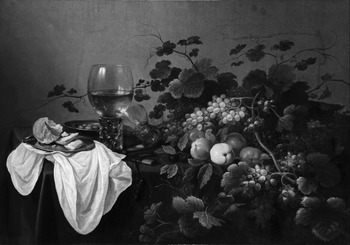

Before turning to ancient ‘still-life’ images themselves, I begin by exploring their delineation as ‘still lifes’ in the first place. For modern viewers, the very category of the ‘still life’ brings to mind a coherent genre of images – above all, those originating in Protestant Flanders from the late sixteenth century onwards: whether a bowl of fruit on a table, a painted bouquet of flowers, or some other artful arrangement of inanimate things, ‘still lifes’ are broadly understood as images for pondering and contemplation.Footnote 18 Figure 4.3, signed by Peter Claesz and Roelof Koets, is just one representative example, with its rich abundance of light-reflecting fruits, its silver platter of broken bread and its translucent display of a water-filled glass.

Figure 4.3 Peter Claesz and Roelof Koets, Still Life with Fruit and Roemer, 1648. Budapest, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. 53.478.

Whichever example we think of, our conceptual frame of the ‘still life’ coheres around a set of common assumptions about artistic purpose and meaning. For those moulded within a German Enlightenment tradition, the still life caters to a gaze of pure aesthetic contemplation. Communicating through internal artistic qualities alone, and lacking any overt visual narrative, the still life might be said to champion a Kantian aesthetic of disinterested pleasure – of ‘purposiveness without a purpose’ (‘Zweckmäßigkeit ohne Zweck’).Footnote 19 Arthur Schopenhauer epitomised this rhetoric in his 1819 book, Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (‘The World as Will and Representation’). Flemish Still lifes, Schopenhauer argued, reveal the true nature of things by liberating us from our enslavement to the ‘will’. Through its very achievement of representational ‘stillness’, the still life presents us with something that ‘real’ life – that is, the transient world that lies beyond the frame of artistic representation – cannot: nourishing our creative imagination (‘Vorstellung’), still lifes provide images of not just food, but also, as it were, food for thought. By looking into the aesthetic frame of these paintings, we can aspire to free ourselves from our material appetites – to become the subjects of a ‘will-less’ knowing.Footnote 20

Figure 4.4 Vincent Van Gogh, Old Shoes with Laces (1888). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv. 1992.374.

Martin Heidegger advanced a different but related argument in his celebrated essay on Der Ursprung des Kunstwerkes (‘The Origin of the Work of Art’), first published in the mid 1930s.Footnote 21 According to Heidegger, the true artwork can remove us from the vicissitudes of the specific and familiar, granting access to the universal essence of things. Heidegger did not look to the sorts of Flemish paintings which Schopenhauer discussed, nor indeed to images of food specifically. But he did nevertheless return to the modern genre of ‘still life’, analysing Van Gogh's painterly treatments of peasant shoes (Figure 4.4 provides one example, set against red and pastel tiles). ‘As long as we only imagine a pair of shoes in general, or simply look at the empty, unused shoes as they merely stand there in the picture, we shall never discover “what the equipmental being of the equipment in truth is” (“was das Zeugsein des Zeuges in Wahrheit ist”)’, Heidegger opines.Footnote 22 In the hands of Van Gogh, however, an image of shoes has the phenomenological potential to launch us into a wholly more essential set of reflections:Footnote 23

This equipment is pervaded by uncomplaining anxiety as to the certainty of bread, the wordless joy of having once more withstood want, the trembling before the impending childbed and shivering at the surrounding menace of death. This equipment belongs to the earth, and it is protected in the world of the peasant woman. From out of this protected belonging the equipment itself rises to its resting-within-itself [Aus diesem behüteten Zugehören ersteht das Zeug selbst zu seinem Insichruhen]. But perhaps it is only in the picture that we notice all this about the shoes. The peasant woman, on the other hand, simply wears them.

For the peasant woman to whom they belong, the shoes are not a subject of contemplation: they are practical objects, one that she barely looks upon (‘sie gar anschaut’). For the viewer of the painting too, the subject might be dismissed as a ‘pair of peasant shoes and nothing more’ (‘ein Paar Bauernschuhe und nichts weiter’). ‘And yet’ (‘Und dennoch’), Heidegger continues, the painting invites a wholly more creative form of subjective reflection, taking viewers beyond the realm of ‘use’ (‘Gebrauch’). The very frame of the representational picture proves critical here: ‘but perhaps, it is only in the picture that we notice all this about the shoes’ (‘Aber all dieses sehen wir vielleicht nur dem Schuhzeug im Bilde an’). In this phenomenological sense, the picture might be thought to ‘deconceal’ something: however parergonal its represented subject, ‘still lifes’ shed light on the aesthetic dimension that necessarily frames all artistic representation; ‘the artwork lets us know what shoes are in truth’ (‘Das Kunstwerk gab zu wissen, was das Schuhzeug in Wahrheit ist’).Footnote 24

Heidegger's comments lead squarely back to the phenomenology of framing: for Heidegger, it is the very frame of the picture that demarcates the special realm of the ergon (in the Kantian sense); for all the parergonal trappings of its subject, the frame of artistic representation turns these shoes into a Kunstwerk. But Heidegger's essay also returns us to ideas about the still life specifically. Whatever else we make of this aestheticising rhetoric, a problem lies in assuming that such modern aesthetic modes, so embedded in our collective post-Enlightenment western consciousness, are common to other times and places. Even in the seventeenth century, this framework looks conspicuously out of place.Footnote 25 To the Calvinist eye of seventeenth-century Holland, arguably more attuned to the religious symbolism of objects than to any pre-Kantian critique of art's metaphysical power, ‘still lifes’ evidently dealt a religious lesson in the way of all flesh (and hence, by extension, the vanity of riches).Footnote 26 Although artists and viewers were of course sensitive to what Svetlana Alpers has called the ‘art of describing’ (and to what Hanneke Grootenboer has likewise more recently termed the ‘rhetoric of perspective’),Footnote 27 this formal concern seems to have operated within an overarching theological framework: the more convincing the descriptive quality of the painting, after all, the more pressing its Calvinist message of nihil est in rebus.Footnote 28 Merely to call seventeenth-century Flemish paintings ‘still lifes’ is therefore to surround them in posthumous assumptions about the genre. ‘Still life’, ‘choses mortes et sans mouvement’, ‘nature inanimée’, ‘nature morte’, ‘Stilleben’: these are primarily eighteenth-century terms, retrospectively applied to a Flemish culture whose ‘ways of seeing’ were in fact rather differently comprised.Footnote 29 We are back once again with the central issue of framing – albeit, in this case, with the discursive frames of verbal language: our modes of viewing these paintings, we might say, are contained and constrained within our own interpretive systems, themselves bound up with the cultures of post-Enlightenment ‘art’.Footnote 30

The problem of anachronism is all the more conspicuous when dealing with the ‘still lifes’ of antiquity.Footnote 31 Wherever we look, we find an overarching (and deeply romantic) scholarly assumption about a continuous aesthetic tradition of the still life, and one that stretches the longue durée between antiquity and modernity. Take the following assessment by Guy Davenport (although admittedly dealing with Roman mosaics rather than paintings):Footnote 32

A Roman landscape in mosaic on the wall of a villa…is a vision radically different from a medieval landscape with its toy charm and fidgety business…or a Poussin, or a description by Proust of the meadows around Balbec…But a Roman mosaic of a basket of apples and pears…is wonderfully like baskets of apples and pears of all ages. There is the same nakedness of presentation, the same mute hope of and confidence in the clarity of the subject.

For all their differences in disciplinary perspective, the same sorts of thinking characterise classical archaeological analyses of Campanian ‘still-life paintings’. There have been five important catalogues of such paintings over the last century (by Beyen, Rizzo, Eckstein, Croisille and de Caro),Footnote 33 and ‘still lifes’ have also been treated in a plethora of shorter discussions.Footnote 34 Yet common to the vast majority of these analyses has been the assumption that responses to ancient ‘still lifes’ were structured around modern aestheticising agendas. As Jean-Michel Croisille argues in what is still the most detailed catalogue of natures mortes campaniennes (published in 1965), ‘still-life’ paintings are thought to have been motivated by ‘l'intérêt, plus désintéressé et raffiné, de la contemplation des objets pour eux-mêmes, dans la beauté simple de leurs formes et de leurs couleurs’.Footnote 35 Stelios Lydakis’ glossy 2004 catalogue of Greek Painting goes even further, at once extracting extant Pompeian paintings from their original mural contexts, and reframing them in a pictorial spread alongside the works of Frans Snyders, Peter Claesz and others: the associated invitation is for readers to observe the shared ‘compositional structure’ that unites these paintings across time and space.Footnote 36 ‘Not till the Dutch still lifes of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries’, as Roger Ling succinctly concludes, ‘were the aesthetic qualities of food and inanimate objects so effectively recaptured in painting’.Footnote 37

Such conceptual delimitations of Roman ‘still-life’ images have gone hand in hand with the delineation of their formal boundaries. In many cases, our very frameworks for approaching the ‘still life’ have determined the literal frames in which these paintings are presented and visually reproduced.Footnote 38 Like so many other Campanian paintings, the vast majority of so-called ‘still-life’ images discovered in Pompeii and Herculaneum in the eighteenth century were removed to the archaeological museum at Naples, displayed alongside other instances of (what were taken to be) the same artistic genre: out of the 340 images that Croisille analyses, a staggering 147 paintings were removed to Naples to be catalogued together as ‘genre’ paintings.Footnote 39 In other museums too – and across a remarkably wide geographical span – the supposed ‘still lifes’ of Campanian painting have lent themselves to the metaphorical and literal frames of the modern gallery: consider, for example, a fresco fragment in Chicago's Art Institute, now displayed behind glass in a double-mounted gilded frame (alongside a label that declares the work a ‘still life, including a platter with vegetables, a pinecone, [and] garlands’) (Figure 4.5).Footnote 40 Whatever its original mural context, this panel has been thoroughly ‘Alma-Tadematised’ (cf. Figures 4.1 and 4.2): within the framework of the museum, it is presented as an autonomous, self-contained artwork.

Figure 4.5 Photograph of a Campanian ‘still life’ as displayed in the Art Institute at Chicago. Chicago, Art Institute (on loan from the Field Museum, inv. 24654).

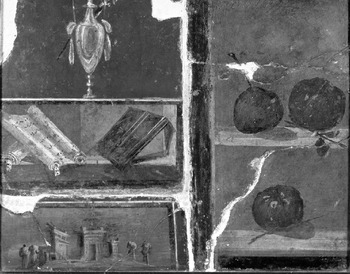

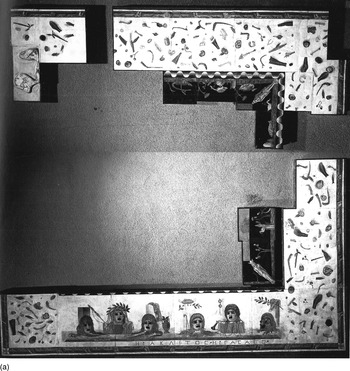

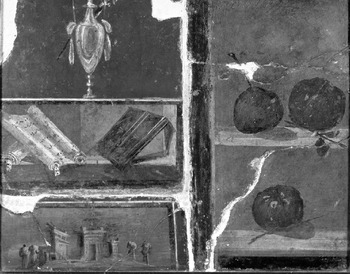

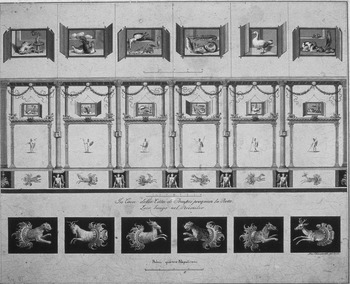

Figure 4.6 Composite painting made from different fragments of Campanian ‘still-life’ paintings collected in the eighteenth century. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. 9819.

Given the physical excision of such images from their mural frames – hung in the museum like the self-contained easel-paintings of the gallery – it is perhaps not surprising that these decontextualised chunks of painted plaster have turned into ‘still lifes’ in the familiar modern sense. A number of paintings have even been lined up and joined together to form composite friezes – not only deframed from their original mural contexts, but also reframed in an attempt to satisfy modern generic expectations. This is true of ‘two’ framed images in Naples (inv. 8645 and 8644), both comprised of paintings taken from the Casa dei Cervi in Herculaneum (IV.21).Footnote 41 But it is also true of a ‘third’ example in Naples (inv. 9819), this time made up of four separate fragments of unknown provenance (Figure 4.6).Footnote 42 Each of the fragments contained within this ‘single’ framed panel seems to have come not only from different paintings, but also from different houses (and perhaps even from different towns): one depicts a silver urn, a second shows book scrolls, a third a rustic shrine and a fourth a collection of fruits. For those who constructed the painting in the eighteenth century, however, these decontextualised fragments could satisfyingly be reframed as a single ‘still-life’ composition – an independent aesthetic assemblage with its own autonomous frame.

If Figure 4.6 testifies to the ways in which archaeologists have tended to approach ancient ‘still-life’ paintings within the hermeneutic frameworks of modern art history, its constitutive components also bear witness to the specific visual subjects of that assumed ‘still life’ genre. Whichever catalogue of ancient ‘still lifes’ we consult, we find related modern criteria defining the boundaries of the genre. This is surely the reason why images of books and writing equipment – so-called instrumenta scriptoria (cf. Figure 4.6) – are recurrently incorporated within ancient ‘still-life’ catalogues, aligning as they do with the subjects of still-life paintings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries;Footnote 43 conversely, it is perhaps why trompe l’œil painted garlands and associated ‘garden’ scenes, which cannot so easily be connected with the modern genre, are omitted.Footnote 44 Our modern hermeneutic frameworks likewise explain why Croisille's catalogue of Campanian ‘natures mortes’ omits ‘tableaux à animaux’ (so-called Tierstücke), and in particular why it limits itself to autonomously ‘framed’ images – that is, to paintings set off from their mural schemes in bounded panels (excluding images organically incorporated into trompe l’œil schemes): just as the very framework of the ‘still life’ relies on the aestheticising excision of its subject matter from the everyday world of mundane reality, so too does Croisille's catalogue restrict itself to pictures laid out in self-standing frames.Footnote 45 In deciding which images to include within the category of the ancient ‘still life’, and by extension which images to keep out, we have applied a set of anachronistic criteria: it is our modern frames – bounded by the associated frameworks of a much later artistic and aesthetic tradition – that have structured a critical approach.

One question that results from this scenario is whether or not we can talk about ancient ‘still lifes’ as a self-standing category of ancient artistic production. A second – and closely related – question is whether or not we can find a related language in which to discuss Campanian ‘still-life’ paintings in ‘emic’ historical perspective. In response to both questions, scholars have traditionally turned to literary texts, and to two Latin passages in particular. The first comes from Vitruvius’ late first-century BC On Architecture. Explaining the differences between Greek and Roman domestic architecture, Vitruvius provides an apparent aetiology for paintings of food:Footnote 46

For when the Greeks were more luxurious – when they found themselves in more opulent circumstances – they provided for their visitors, upon their arrival, dining-rooms, bedrooms and storerooms with supplies. On the first day, they invited them to dinner; afterwards, they sent poultry, eggs, vegetables, fruit, and other such rustic produce [res agrestes]. That is why painters, when they replicated in their paintings the things sent to guests, called them xenia [ideo pictores ea, quae mittebantur hospitibus, picturis imitantes xenia appellauerunt]. Thus the heads of a family in a guesthouse do not seem to be away from home, enjoying private generosity in their guest-quarters.

The importance of this text has been deemed to lie in the apparent terminology that it bestows, grouping together paintings of rustic produce under the title xenia, or ‘guest gifts’.Footnote 47 For some critics, the term xenia has served as a simple way of imposing the modern genre onto ancient thought and practice. Norman Bryson's sophisticated analysis of ancient ‘xenia’-paintings provides just one example. Although insistent about the importance of ancient terminology – after all, he concedes, it is all too easy for ancient paintings to be ‘elided with images produced under quite different cultural conditions’ – Bryson nevertheless maintains that xenia comprised ‘a category much resembling what would later be called “still life”’.Footnote 48 Bryson is explicit about this essentialist and universalising attitude, arguing that ‘still life as a category within art criticism is almost as old as still life painting itself’;Footnote 49 for Bryson, moreover, this is a meaningful category ‘not only within the reception and criticism, but within the historical production of pictures’.Footnote 50 In my view, we should exercise considerable caution here: whatever else we make of Vitruvius’ term, after all, it is significant that it recurs in only a handful of other Latin contexts, none of them associated with painting.Footnote 51

When read in its own terms, Vitruvius’ passage gives some important additional insights about the hermeneutic frameworks surrounding the images that we shall explore in this chapter. If Vitruvius frames such paintings with ideas about luxuria, no less than about ‘Greekness’, his very talk of their different display contexts points to the transportability of the underlying themes. As artistic motif, Vitruvius informs us, xenia are not topographically specific to particular types of room, but instead depict subjects that are suitable in different sorts of spaces – dining-rooms, bedrooms and supply-rooms.Footnote 52 In doing so, Vitruvius suggests that xenia could be reframed as painted subjects to suit multiple contexts: his comments chime with a certain idea about the ‘transferability’ of these motifs, attesting to their literal and metaphorical portability – whether integrated within the illusionistic schemes of the wall, as we shall see, or else reframed as (make-believe) portable panels. At the same time, it is worth noting how Vitruvius frames such images within the language of replication: these images are defined first and foremost as real-life gifts that painters ‘imitate in their pictures’ (picturis imitantes).

The second text to which scholarship has referred comes in Pliny the Elder's first-century AD Natural History, discussing an otherwise unknown painter named Piraeicus. After surveying the grand masters of Greek painting, Pliny turns to what he calls a ‘lesser style of painting’ (HN 35.112), including the depiction of viands, or obsonia:Footnote 53

For it is fitting to add something about the artists whose fame for the brush stems from smaller painting [minoris picturae]. Among these was Piraeicus, who should be ranked below few in skill. It is possible that he won distinction by his choice of subjects, inasmuch as, although adopting a humble line, he nevertheless attained in that field of humility the pinnacle of glory [quoniam humilia quidem secutus humilitatis tamen summam adeptus est gloriam]. He painted barbers’ shops, cobblers’ stalls, asses, viands [obsonia] and the like: consequently, he received the [Greek] name ‘painter of sordid things’ [rhyparographos]. In these paintings, however, he gives exquisite pleasure; indeed, they fetched bigger prices than the largest works of many [in iis consummatae uoluptatis, quippe eas pluris ueniere quam maximae multorum].

We know nothing about ‘Piraeicus’ other than what Pliny tells us in this short passage.Footnote 54 Still, this has not stopped scholars from attempting to construct a whole life history for the painter. Piraeicus is sometimes deemed to have worked in Hellenistic Alexandria, in what Charles Sterling confidently calls a ‘familiar line of evolution’:Footnote 55 Piraeicus, the reasoning runs, must have worked at a time when, just as in seventeenth-century Holland, attention turned from the grand subjects of the ‘Classical’ Renaissance to the mundane subjects of the ‘Hellenistic’ Baroque.Footnote 56 Piraeicus, in G. E. Rizzo's terms, was thus the ‘pittore “olandese” dell'antichità’.Footnote 57

One of the reasons why this Plinian text has proved so appealing to modern readers is its seemingly disparaging dismissal of Piraeicus as rhyparographos, or ‘painter of sordid things’. The historical context of Piraeicus – and above all his choice of artistic subjects – is accordingly reframed in terms of later European art history, and above all the pejorative critical interpretation of Flemish still-life painting in the art academies of the eighteenth century: Pliny's associated talk of minoris picturae (literally ‘smaller painting’, but usually translated as ‘a lesser style of painting’) has been interpreted as incontrovertible evidence that in antiquity, just as in the eighteenth century, ‘still lifes’ were judged ancillary to the more important genres of historical and mythological paintings.Footnote 58 This diminutive framework for discussing the ancient material has very much endured. ‘Subsidiary motifs’ and ‘stock fillers used by painters to save time’: that is how Roger Ling describes ‘still-life’ paintings surviving from Pompeii and Herculaneum,Footnote 59 just as Andrew Wallace-Hadrill constructs a whole hierarchy of Roman painting (deeming ‘landscapes and still lifes’ the least significant).Footnote 60 If many scholars have consequently judged ‘still lifes’ an ‘inferior’ sort of painterly subject, they have also assumed a hierarchical distinction between the realms of figure and ornament (no less than between peripheral frame and central panel); in doing so, there has been a tendency to undervalue the subtle interplay of different representational elements, thereby overlooking the complex framing of these issues within the larger cultural and representational frameworks of Roman fresco-painting.Footnote 61

Regardless of whether or not Campanian paintings have any connection with the obsonia images that Pliny describes (just how ‘sordid’ their subjects remains far from clear), Pliny's evaluation is rather more ambiguous than most scholars have supposed. Observe, for example, how Pliny relishes the paradox that, despite their small-scale subjects, these paintings were enjoyed above all others (consummatae uoluptatis). Indeed, it is worth noting that, despite their smaller size and subjects, they are said to have fetched more money than even the biggest works of many other painters.

So much for the Roman literary evidence. But what of actual extant images? When turning to Campanian wall-paintings, one of the most striking features of such ‘still-life’ imagery is its sheer popularity. Of course, we might expect paintings of food to have been prevalent in the dining spaces of the triclinium, associated with the themes of feasting and hospitality. But far from adorning triclinia alone – still less the triclinia of ‘more modest houses whose owners could not afford the luxury of a mythological picture’, as Roger Ling positsFootnote 62 – depictions of food recur throughout the Roman house. Indeed, they frequently appear in its most conspicuous and important rooms – tablina, atria and peristyles, for instance.Footnote 63 Just as our quoted Vitruvius passage implies of the ‘original’ xenia lying figuratively behind these representations, painted foodstuffs evidently amounted to transferable sorts of images, suitable for all manner of different domestic contexts. The very popularity of these motifs subsequently calls for a wider-ranging analysis. And this in turn requires us to try and think beyond our modern aestheticising frameworks – above all, by considering how ‘still lifes’ were framed within their original mural schemes.

Framing Representation and the ‘Four Styles’ of Pompeian Painting

Precisely because so many ‘still-life’ panels were physically removed from their walls in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it can be difficult to reconstruct their original mural contexts – a case, as we have said, of our theoretical frameworks governing the physical frames of modern display (and vice versa).Footnote 64 Still, enough paintings do survive either in situ or with secure provenance to warrant that attempt. In what follows, I therefore investigate the physical frames of Campanian mural-paintings to explore the particular cultural historical frameworks operating behind them: as we shall see, the ways in which surrounding walls framed images of food, and by extension the ways in which images of food in turn framed their mural surrounds, directly bore upon a viewer's impulse either to look through the wall, or else to see it as the spatial limit of the room.

Before explaining what I mean here, it is necessary to say something about traditional scholarly schemes for approaching Campanian mural frames, and in particular about the system devised by August Mau during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 65 In delineating between what he labelled the ‘Four Styles’ of Pompeian painting, Mau's objective was to determine an evolutionary history of stylistic sequence that could date, albeit relatively, any extant example. Starting out from Vitruvius’ disparaging comments about new-fangled styles in the late first century BC,Footnote 66 Mau developed a four-tiered typology which charted developments between the second century BC and the late first century AD (the Vesuvian explosion of AD 79 forming the key chronological terminus). We move progressively from the mock-masonry blocks of the First Style, through the illusionistic architectural vistas of the Second, to the Third style, with its artful alignment of restrained centrepieces and symmetrical patterns, and finally on to the Fourth, which combines elements of the Second with aspects of the Third. Mau made no secret of his own aesthetic preference: if the Third Style marks an acme of Roman artistic achievement in wall-painting, the Fourth, with its exuberant extravagance, reflects its baroque (‘over-the-top’) decline.Footnote 67

Mau has had a mixed reception in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. While many scholars have tended to refine his chronological scheme, recent anglophone scholarship has taken issue with his assumptions head-on, substituting his formal analysis with a more contextual mode of interpretation, and paying special heed to mythological assemblage, visual narrative and domestic setting.Footnote 68 This has gone hand in hand with a chronological critique. Mau's system of linear progression, it is rightly said, overlooks the fact that different mural schemes coexisted at one and the same time.Footnote 69

As so often with revisionist scholarship, there seems a danger here of throwing out the metaphorical baby with the bathwater. For all his chronological assumptions, Mau demonstrated an exemplary sensitivity to the importance of overall design. Where he took an holistic view of the overarching significance of different mural schemes,Footnote 70 more recent work has sometimes tended – rather like the Alma-Tadema painting with which we began (Figure 4.1) – to approach extracted mural panels in isolation from their larger mural frameworks, assuming a categorical sort of distinction between the realms of ‘figure’ and perergonal ‘ornament’. In treating Roman wall-painting as a sort of ‘interior design’, moreover, some scholars have been swayed by anachronistic notions of Neoclassical decoration (taking their lead from the ‘Pompeiana’ of the British aristocracy). Still more critically, scholarship can sometimes lose sight of the single variable which Mau deemed so important in Pompeian wall-painting – and which he therefore, following Vitruvius, understood to govern its evolutionary trajectory: namely, that of pictorial illusion. Most valuable in Mau's typology, we might say, is not the neat and unidirectional process of chronological development – the aspect that Mau's modern-day followers have tended to champion – but rather his emphasis on the underscoring and dissolution of the pictorial plane.Footnote 71

By thinking about the physical framing of Campanian ‘still-life’ imagery, it is this illusionistic framework that the present discussion sets out to develop.Footnote 72 In what follows, I suggest that mural-painting's formal framing of food motifs in turn framed an interpretive agenda which revolved around the illusory status of the subjects depicted. If my aim is thus in one sense to vindicate Mau, an associated objective is gently to nudge attention towards issues of visual response: where Mau was predisposed to privilege formal analysis, my concern will be with what – and how – illusionistic and anti-illusionistic mural frames might have meant within their original cultural frameworks.Footnote 73

Figure 4.7a Detail of a basket of figs from the north wall of triclinium 14 of the Villa of Poppaea at Oplontis.

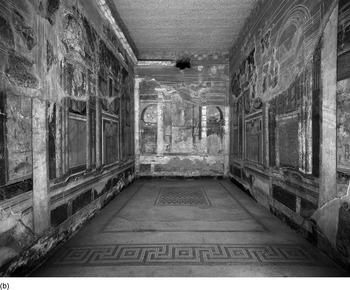

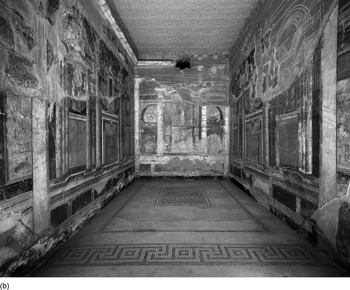

Figure 4.7b West, north and east walls of the same triclinium in the Villa of Poppaea at Oplontis.

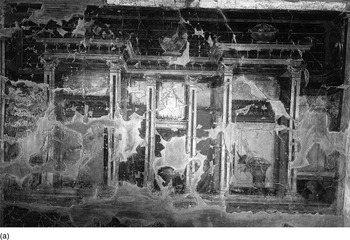

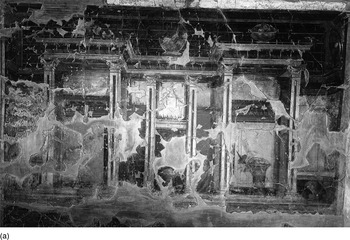

Figure 4.8a East wall of oecus 23 of the Villa of Poppaea at Oplontis. Photograph reproduced by kind permission of the Archiv, Institut für Klassische Archäologie und Museum für Abgüsse Klassischer Bildwerke, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich.

Figure 4.8b Detail of calathus framed in the projecting scaenae frons on the east wall of the same oecus at Oplontis. © Scala/Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo/Art Resource, New York.

Allow me to begin with the incorporation of food and fruit motifs in mural schemes of the Second Style, and in particular with the so-called Villa of Poppaea at Oplontis.Footnote 74 Images of fruit appear prominently in two Second Style rooms at Oplontis (room 14 and oecus 23), taking their place amid a variety of architectonic trappings.Footnote 75 Figure 4.7a shows just one detail – a basket of green and purple figs from the north wall of room 14 (Figure 4.7b), two of them so ripe that they have burst through their skins;Footnote 76 on the left-hand side of the same wall, occupying the same position as the fig-basket, and again set against the painted blue vista, we see a glass bowl of fruit. Such fruit-filled glass bowls recur on the east wall of oecus 23 (Figure 4.8a), this time perched on small pedestals on the upper ledge of the painted scaenae frons (with each pedestal painted in accordance with the perspective from which the architecture below is seen).Footnote 77 Framed inside the room's projecting architectural structure is also a wicker-basket, or calathus, covered with a transparent veil (which offers a teasing glance at the apples and prunes contained within) (Figure 4.8b): the basket is made to stand as if in front of the rear painted wall but behind the architectural ledge.Footnote 78

It is important to emphasise that, within Second Style painted schemes like the ones at Oplontis, such images of fruits are not formally framed as self-standing panels. Instead, each bowl, basket and container is surreptitiously placed within the mural framework of the illusionistic architectural structure: both Oplontis rooms integrate their painted fruits within the illusionistic space of the wall, as if replicating the sorts of real-life res agrestes that Vitruvius mentioned in his account of xenia. In this sense, the make-believe of the receding mural structure is bound up with that of the depicted fruits. Each frames the other in a mutually implicative way: the mimetic simulation of the figs and apples rests in part on the replicative persuasiveness of the painted architecture, and vice versa. Such illusionism can be related to the Second Style at large, as Wesenberg has argued, with its various attempts to elide the real space of a room (‘Realraum’) with the representational space of its depicted forms (‘Bildraum’).Footnote 79 At the same time, the specific recourse to images of fruit finds numerous parallels both on the Bay of Naples and in Rome: painted bowls of fruit, again resting on painted architectural ledges, beams and supports, can be found in the Second Style decoration of the so-called ‘Room of the Masks’ in the so-called ‘House of Augustus’ on the Palatine,Footnote 80 for instance, as well as in cubiculum M of the Casa di Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale (cf. Figures II.3 and II.5).Footnote 81 We might note in passing that, among contemporary scholars, many of these same rooms have also given rise to debates about linear pictorial perspective in antiquity.Footnote 82 Within such feats of replicative trompe l’œil, painted fruits added the figurative ‘cherry on top’: they recur precisely in those scenographic scenarios where the painted mural schemes have us think that we might be looking beyond (or perhaps rather through) the containing frame of the wall.

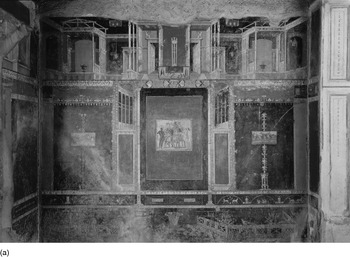

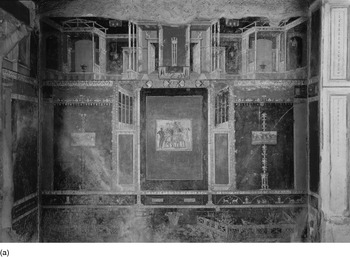

So far, we have examined the ‘unframed’ images of foodstuffs in Campanian painting – that is, images that are integrated within the larger illusionistic frameworks of the Second Style. But such schemes provide only one visual surround. When we look to walls of the Third and Fourth Style, the framing works very differently.Footnote 83 Tablinum 7 of the Casa di M. Lucretius Fronto (Pompeii V.4.11) offers just one Third Style case study.Footnote 84 Framed paintings of fish appear on both the north and south walls of the room (Figures 4.9a–b): in a self-standing panel in the central upper section of the north wall, two groups of three fish lie on a window ledge above three pairs of fish below; in a parallel composition occupying the same space on the south wall, two single hanging fish flank a window, with its basket spilling its contents onto the space below. On each wall, these compositions take their place within a larger decorative scheme, structured around a central self-standing mythological panel (offset in red and black), with two miniature villa ‘landscapes’ on each side (supported by elaborate candelabra structures). In the centre of the wall's fanciful upper structures, set off against a yellow background, we find receptacles rather like those encountered in earlier Second Style schemes – albeit this time these are empty vessels, devoid (so far as we can see) of fruits within.

Figure 4.9 (a) North wall of tablinum 7 of the Casa di M. Lucretius Fronto, Pompeii (V.4.11). (b) Detail from the south wall of the same tablinum.

As for the two fish-paintings themselves, it is worth noting the highly contrived frame. Each panel is surrounded by a thick black border, and each incorporates within it an additional recessed ledge (supporting an assemblage of fish on the south wall, and an upturned basket on the south – the motion of its spilt fish ‘stilled’ in time); in each case, moreover, the fish have been specially arranged, with their tails obligingly curled so as to fit within the frame. While the recessed ledges within each framed picture visually echo the stylised architectural recessions surrounding them above and to the sides (complete with shuttable doors), the panels are clearly demarcated as separate from the wall. The very framing of the images, then, serves to insert them in figurative quotation marks. The literal frame of the picture frames our view of it as a self-standing representation, depicted at second remove from the mural scheme in which it appears: the panel creates its own representational world, one physically and metaphorically detached from both the wall's painted architectural fancies and the real space of the room.Footnote 85

Related Third Style examples could be introduced here. But my emerging suggestion is that images of food, integrated within different stylistic frameworks, played a decisive role in constructing (as indeed deconstructing) the ontological register of the painted wall. Second and Third styles framed food images in very different ways: while Second Style schemes tantalisingly whet the viewer's appetite, integrating bowls and baskets of fruit within their illusionistic vistas (and thereby making those vistas out to be more than paint and pigment), they necessarily thwart such consumption.Footnote 86 Despite the palpable differences in frame, both schemes exploit consumable subjects as an index for the simulative or dissimulative framework of the wall, just as the framework of the wall provides a way of gauging the virtual reality of this food imagery.

This leads directly to Fourth Style frames, with their simultaneous fusion of Second Style illusionism with Third Style anti-illusionistic elements.Footnote 87 Once again, we find images of food being used to interrogate the boundaries between reality and replication; framed in self-standing panels, moreover, food motifs are exploited to underscore and destabilise the fictive semblance of the overarching mural scheme. In Fourth Style walls, such images are often set off as delicate ‘miniatures’ within overriding swathes of colour. Sometimes, they are incorporated within stylised circular panels (as for example in tablinum F of the Casa dell'Ara Massima, Pompeii);Footnote 88 at other times, the very scale of the depicted objects is distorted – both the size of the framed objects in relation to the wall in which they were set,Footnote 89 and the respective scales of different objects within a single composition.Footnote 90

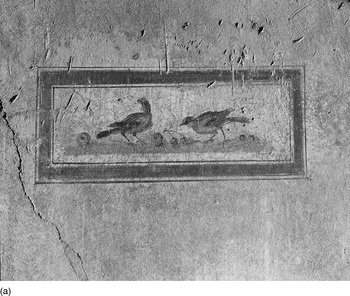

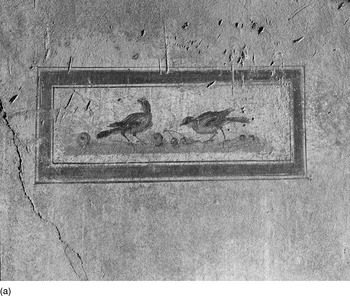

Among the most striking aspects of Fourth Style walls is their framed inclusion of not just fruits, but also birds interacting with them.Footnote 91 In some schemes, these are set off from the wall in clearly demarcated panels: Figure 4.10a, for example, shows two sparrows inspecting cherries and plums (surrounded by a tripartite frame), while Figure 4.10b portrays a cockerel pecking at an open pomegranate and pear. On other occasions, and nowhere more prominently than at Oplontis, we find this subject floating on a flat monochrome ground (e.g. Figure 4.10c): in keeping with the move from Third to Fourth Style framing systems more generally, the motif is extracted from any architectural or panelled scheme, raising larger questions about the porous boundaries between not only frame and framed, but also thereby between the figurative and the ornamental. It is worth noting the iconographic continuity with earlier paintings too: the basket of figs in Figure 4.10d (an unprovenanced painting from Pompeii), for example, looks almost as though it has been lifted from the Second Style trappings of our Oplontis triclinium (Figure 4.7a) – albeit now set on a shelf within a self-standing framed panel, and once apparently contained within a Fourth Style wall.Footnote 92 While suggesting the aperture of a window, as though viewers could look through the wall (a topos that Roman wall-painting of course played with in knowing and self-referential ways: cf. Figure 1.22), the frame here serves itself to frame the mimetic artifice involved: the figs may be lifelike enough to attract the attention of birds (at least within their frame), but the panelled edges simultaneously contain the picture as a figment of self-contined artifice.

Figure 4.10a Painting from portico l in the Casa del Principe di Napoli, Pompeii (VI.15.7–8). Photograph reproduced by kind permission of the Archiv, Institut für Klassische Archäologie und Museum für Abgüsse Klassischer Bildwerke, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich.

Figure 4.10b Unprovenanced painting from Pompeii. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. 86719. © Scala/Art Resource, New York.

Figure 4.10c Detail from the east wall of room 81 in the Villa of Poppaea at Oplontis. © Scala/Art Resource, New York.

Figure 4.10d Unprovenanced painting from Pompeii. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. 8640. Photograph: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Rom (D-DAI-Rom 1960.2412; photograph by Sansaini).

How should we explain such images of birds and fruit? If the motif takes us back to the overriding themes of artifice and illusion – themes, as we have seen, expressly framed by the different surrounds of Campanian wall-painting – it might simultaneously bring to mind a specific anecdote of virtuoso artistic illusion. In the thirty-fifth book of his Natural History, Pliny the Elder tells the story of an artistic competition (certamen) between Zeuxis and Parrhasius, both working in the early fourth century BC (HN 35.65).Footnote 93 So successfully (tanto successo) did Zeuxis paint a bunch of grapes, we are told, that birds flocked around its promised fruits, ‘flying up into the scene’ (ut in scaenam aues aduolarent); undeterred, Parrhasius responded to his rival by painting a curtain, and did so with such representational realism (ita ueritate repraesentata) as to hoodwink Zeuxis himself. After instructing Parrhasius to remove the curtain and reveal the image beneath, Zeuxis realises his mistake (intellecto errore) and concedes victory: ‘whereas Zeuxis had deceived birds, Parrhasius had deceived him, a painter’ (quoniam ipse uolucres fefellisset, Parrhasius autem se artificem).

Figure 4.11 Adriaen van der Spelt and Frans van Mieris, Trompe-l’œil Still Life with a Flower Garland and a Curtain, 1658. Chicago, Art Institute, inv. 1949.585.

Frames prove fundamental to this story of ‘truth’ (ueritas) and (mis)understanding: just as the birds were deceived by the imagery within the replicative frame of Zeuxis’ artistic representation, so Zeuxis mistakes Parrhasius’ painted image for the peripheral frame of its protective outer curtain.Footnote 94 Within western art history, Pliny's tale is deeply familiar – thanks in part to the self-referential visualisations by later artists, and not least to post-Renaissance images that played upon the underlying topoi (e.g. Figure 4.11).Footnote 95 But it is worth remembering that Pliny's story is structured, first and foremost, around the convincing representation of painted fruit.

Whether or not they knew this specific anecdote (or indeed other associated stories of virtuoso illusionism), Fourth Style mural-painters certainly seem to have recognised its underlying layering of representational registers: playing knowingly with associated discourses of artistic illusion, they sometimes even insert both illusory stimulus and deluded birds into their mural frames. In doing so, Fourth Styles schemes simultaneously collapse and underscore the different representational levels involved. On the upper west wall of tablinum I in Pompeii IX.2.10 (Figure 4.12), for example, we find not only the painted image of a rooster pecking at grapes (complete with basket of figs to the left) (cf. Figure 4.10b), but also a painted curtain above, illusionistically draped over the scene. The combination of motifs might be said to anticipate the sorts of replicatory games which later western artists relished (cf. Figure 4.11): if the cloth's embroidered pattern visually echoes that of the lunette's ‘ornamental’ semicircular surround, the motif of fruit and birds is replayed in the additional panels offset within the tablinum's Fourth Style mural and ceiling decoration, which contains offset vignettes of sparrows eating fruit (e.g. Figure 4.13), as well as free-standing bird motifs against the wall's monochrome red background.Footnote 96 So are we to think that an (unconvincing?) bird is to be convinced by these painted fruits, but that human viewers are not? Or does the fact that this is a painted bird undermine the berries’ capacity for illusion (and vice versa)? On the one hand, by incorporating within the fictional frame of the wall-painting not only ‘realistic’ grapes, but also the legendary birds that (mis)took those grapes for reality, such images might be said to trump even Zeuxis’ virtuoso trompe l’œil. On the other hand, the whole feat of illusion is staged here with a knowing degree of replicative self-referentiality – a self-consciousness about the interventions of different representational registers.Footnote 97

Figure 4.12 Detail from the upper west wall of tablinum I at Pompeii IX.2.10.

Figure 4.13 Detail of the painted ceiling decoration of tablinum I at Pompeii IX.2.10.

Framing, it seems to me, plays a central role in such mimetic games. To extract such ‘still lifes’ from their original mural contexts, privileging an anachronistically modern aesthetic framework, is to overlook the illusionistic discourses that once (again both literally and metaphorically) surrounded them. As we have seen, different Campanian mural schemes evidently framed images of food in remarkably different ways. And yet common to all was a concern with the conceptual frame of painterly representation: the divergent frameworks in which images of food were contained amounted to very different claims about pictorial mimêsis. Of course, such blurrings between reality and framed painterly representation emerge as a major topos in ancient Graeco-Roman art criticism – and in responses to free-standing panel-paintings in particular.Footnote 98 While views of our paintings were framed by such discourses, the different mural schemes of the Pompeian Styles place that critical frame at their centre, posing questions (and tantalising us with divergent answers…) about the painted wall's ability to reach beyond the physical constraints of a given space.

Images of food therefore take their place amid the numerous other subjects framed within the walls of Campanian wall-painting. Needless to say, so-called ‘still lifes’ were by no means the only subjects to explore such themes of artistic replication: as Norman Bryson puts it, ‘illusionistic skill…is a precondition of the system rather than xenia's specific objective’.Footnote 99 Nonetheless, I would argue that fruit and other foodstuffs proved a particularly delicious subject for thinking about the consumable illusionism of pictorial representation. One only need think of the frequent recourse to ‘make-believe’ foods for debating the correlations between sense perception and knowledge in ancient philosophy – as demonstrated by the tricks played out on the Stoic philosopher Sphaerus during Ptolemy Philopater's apocryphal dinner party in the third century BC,Footnote 100 for example, and as satirised in Petronius’ account of Trimalchio's own cena (where no foodstuff proves quite what it seems to be).Footnote 101 Again and again, Greek and Roman discussions of empiricism and knowledge frame (make-believe) fruits in related terms: on the one hand, fruit emerges as a pinnacle of objective reality, quite literally incorporated (through the act of consumption) within our bodily frames; on the other, fruits and other foodstuffs are frequently cited as culturally ‘cooked’ things – as objects which can seem other than what they are.Footnote 102 Food made for a particularly appropriate subject within the frames of mural make-believe, we might say, precisely because of its conceptual implications for distinguishing between truth and semblance.

Figure 4.14 Wall-painting from the Casa dei Cervi, Herculaneum (IV.21). Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. 8645A.

Figure 4.15 Painting from the north wall of tablinum 92 of the Praedia di Giulia Felice, Pompeii (II.4.3). Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. 8611B.

Allow me to round off my discussion here with two final observations. The first remains in the realm of Campanian ‘still-life’ painting, and pertains to one recurrent visual topos treated so far only in passing – namely, the frequent depiction of glass vessels containing fruit and other consumable objects.Footnote 103 We have already encountered this motif in our two rooms at Oplontis (Figures 4.7b and 4.8a), where fruits are displayed in transparent glass both within a framed vista and on top of the protruding upper ledge of a scaenae frons; likewise one might compare the glass bowl of fruit incorporated within the multilayered pictorial frames of cubiculum M in the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale (Figure II.5).Footnote 104 Whereas such vessels are integrated within the overarching illusionistic mural schemes, later self-standing panels frequently isolate related glass containers: reframing the motif within the clearly demarcated borders of their pictures, some images juxtapose water-filled glass vessels with their displayed fruits (e.g. Figure 4.14), while others compare and contrast obscuring terracotta containers with large diaphanous bowls filled with fruit (and occasionally place additional ‘unmediated’ fruits at their sides (Figure 4.15). In all these examples, the see-through quality of glass seems to have rendered it a particularly rich medium for visualising the frames of pictorial representation – both the frames of different overarching mural schemes, and those of the self-standing panels framed within Third and Fourth Style walls.Footnote 105 The prismic transparency of glass becomes, as it were, a metaphorical figure for the frame of pictorial representation: the very vessels containing such fruits, themselves contained within the mural (anti-)illusions of the painted wall, mirror the containing mediation of all pictorial replication (as well as the bounded promise of breaking that frame).Footnote 106 As such, glass vessels take their place alongside related containers, tantalisingly placed so as to mediate between frame and framed, no less than between visual object and viewing subject. One might remember, for example, the transparent veil draped over the calathus of fruit in oecus 23 (Figure 4.8b), itself placed (unlike the glass vessels of fruits on the wall's upper make-believe ledges) within the tangible grasp of the viewer.

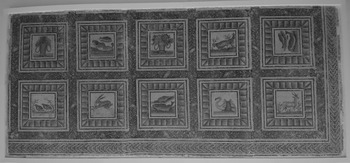

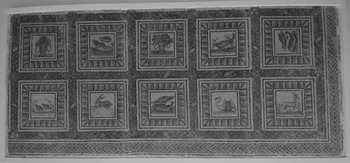

All this corroborates what we have said about the illusionistic frameworks of Campanian painting, and about their interest in food motifs in particular. But my second observation takes us beyond Campania – as indeed the specific medium of wall-painting. After all, the sorts of subjects that we have examined in this chapter were by no means unique to wall-paintings: they recur in other representational contexts too, and above all in Roman mosaics.Footnote 107 Despite the change in medium, Roman mosaics visualise related games of reality and representation, framing them around ideas about art and nature. In numerous examples from North Africa, the sorts of fruits and vegetation that were so often used to frame inner emblemata find themselves framed within the mosaic floor, surrounded by recessions of geometric shapes. Sometimes, we even find intricate garlands of leafs and fruits wrapping around them, blurring the boundaries between the framed images and framing ornament: in a fragment of a once much larger mosaic from El Djem, for example, we find ten inner individual panels featuring so-called xenia motifs (including fruits in wicker baskets, animals and fish), themselves contained in turn within multiple frames, woven together by a complex wreath of leaves, flowers and fruits (Figure 4.16). When it comes to such mosaics, the tessellated medium serves simultaneously to underscore the artifice involved. While framed mosaic panels play with the illusion of real-life fruits and birds flocking round them (e.g. Figure 4.17), the very frame of the mosaic as mosaic in one sense underscores their piecemeal representational status.

Figure 4.16 Mosaic with framed xenia scenes from El Djem. Tunis, Bardo Museum, inv. A 268.

Figure 4.17 Second-century AD mosaic emblem from the ‘Grotte Celoni’ on the Via Casilina in Rome. Rome, Museo Nazionale Romano (Palazzo Massimo alle Terme), inv. 340767.

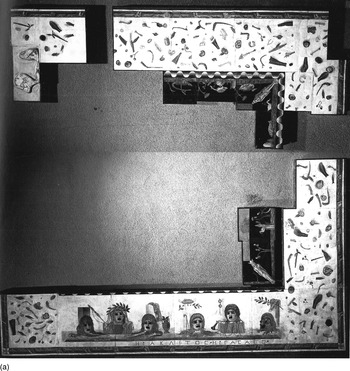

Mosaics like these certainly parallel (and develop) the illusionistic games of wall-painting. But the shift in medium nonetheless changes a viewer's interpretive framework. One of the richest parallels for considering the relationship comes in the so-called asaratos oikos or ‘unswept household’ motif, which Pliny attributes to a very famous (celeberrimus) second-century BC mosaicist named Sosos. In a pavement at Pergamon, we are told, Sosos worked with ‘small cubes tinted in various shades’ to represent ‘the debris of a meal and things which are normally swept away, as if they had been left there (uelut relicta)’ (HN 36.184).Footnote 108 Sosos’ mosaic is lost, but numerous later imitations are known.Footnote 109 In one Hadrianic example – today housed in the Vatican Museums, but deriving from a rich villa to the south of Rome's Aventine HillFootnote 110 – we find related ‘unswept’ panels surrounding a (now lost) central scene on three sides (Figures 4.18a–b). Whatever it originally depicted, the central emblema was surrounded by a series of surrounding frames – including not just the outer asaratos oikos panels (their white ‘floor’ itself mounted on a make-believe architectural platform, albeit one complete with decorative floral designs at the corners), but also an inner black-ground frieze with flowers, animals and Egyptianising motifs. The whole layout of the floor was evidently designed with the room's function in mind. Originally, the room's entrance was flanked by six theatrical masks and an arresting Greek inscription (which names the mosaicist as ‘Heraklitos’).Footnote 111 The three sections of the asaratos oikos motif consequently aligned with the three couches that defined this room as a triclinium; indeed, the representational frame of the mosaic is itself wholly dependent on the real-life frame of the furnished room.

Figure 4.18a Reconstruction of a second-century AD asaratos oikos mosaic. Vatican City, Musei Vaticani (Museo Gregoriano Profano), inv. 10132.

Figure 4.18b Detail of the same mosaic.

Although, once again, the mosaic's frame is very different from the mural frameworks explored in this chapter, it nonetheless delights in the paradoxes of consuming illusionistic art. If the panels scatter all manner of disposed meal debris around this representational space (fish bones, pips, crustacean claws, nutshells, leaves, even in one section a mouse gnawing away at a walnut), they also include the shadows that each object casts against the white floor: the representational frame of the panels – themselves externally framed to resemble a raised platform, and in turn framing the internal emblema at the room's centre – poses (in every sense) as ground. At the same time, however, the tessellated nature of this figured imagery literally and metaphorically fragments the illusion, throwing into relief the simulative make-believe at play (itself bringing to mind Sosos’ renowned artistry as antiquity's celeberrimus mosaicist). Just as the imagery portrays the remnants of a banquet – foodstuffs now ‘emptied’ of their nourishing qualities – the mosaic medium too in one sense ‘un'-represents its consumable subjects.Footnote 112

Conclusion: Frames in Frames

We began this chapter with Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema and his depicted ‘picture-gallery’ of 1864 (Figure 4.1). Alma-Tadema, we have said, exploits the frame to demarcate the privileged aesthetic space of the artwork from the worldly structures that contain it: for Alma-Tadema, as for Kant, the frame materialises a distinction between the true artistic ergon and its parergonal surroundings; as such, the picture-frames replicated within Alma-Tadema's painting mirror the aesthetic affordances of the picture's own external frame, structuring a conceptual parallel between these allegedly ‘ancient’ images and the artwork of Alma-Tadema's self-declared opus. By considering Alma-Tadema's imaginary gallery in relation to the historical schemes of Campanian wall-painting, I hope to have shown the very different affordances of the frame between the modern gallery and Roman mural schemes. So-called ‘still lifes’, I have argued, are particularly rich when it comes to exploring these divergent ‘modern’ and ‘ancient’ frameworks, the one structured around a set of self-standing aesthetic ideals, the other implicated within larger ideas about illusion, replication and make-believe: if food provided a nourishing subject for thinking through the ontology of matter in antiquity, food-paintings provided a good theme for figuring – and above all, for toying with – the ontology of pictorial representation tout court.

It seems fitting, however, to end my chapter by returning to real-life, physical picture-frames like the one that surrounds Alma-Tadema's painting itself (Figure 4.2). After all, self-contained panel-paintings certainly existed in the Graeco-Roman world, called pinakes in Greek, and tabulae in Latin; some are known to have had closable wooden shutters (so-called pinakes tethyrômenoi), resembling two of the panels prominent in Alma-Tadema's painting.Footnote 113 Picture-galleries, or pinacothecae, are also well attested in Roman antiquity:Footnote 114 Vitruvius himself advised about the size, aspect and topographic situation of such rooms (De arch. 6.3.8, 6.4.2, 6.7.3), and there can be little doubt that, beginning with the late Second Style, Campanian mural schemes were frequently designed to emulate these sorts of public and private painting collections.Footnote 115 Extant cavities in Campanian walls likewise suggest practices of ‘reframing’, whereby wooden tabulae could be inserted into mural schemes; indeed, extracted portions of plaster could sometimes be salvaged from one wall and reinserted into another, rather like the ‘deframings’ and ‘reframings’ of more recent times.Footnote 116 The phenomenon leads to a set of fundamental cultural comparative questions. In reframing the extracted wall-paintings from Pompeii and Herculaneum, after all, does Alma-Tadema's painting not in one sense hold true to ancient Roman practice? Do modern aesthetic framing strategies not consequently have ancient precedent? And if so, do the affordances of the frame – at least in the realm of painting – really work so differently between the ancient and modern worlds?Footnote 117

Figure 4.19 Portrait of a woman painted on sycamore-fig wood, set within two frames of sycamore fig and hung with twisted rope; from Hawara in Egypt, mid first century AD. London, British Museum, inv. GRA 1889.10–18.1.

Figure 4.20 Scene of a painter's workshop, painted inside a limestone sarcophagus from Kerch, first or second century AD. St Petersburg, The State Hermitage Museum, inv. P‐1899.81.

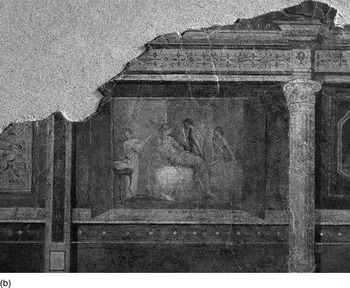

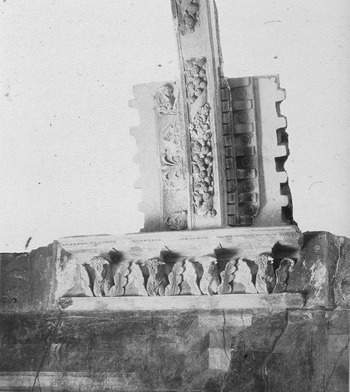

The difficulty in tackling such questions lies in the fact that we have so little material evidence for pinakes and tabulae to go on. In rare cases, exceptional archaeological conditions have led to the preservation of wooden panels complete with their original devices for display (as in a portrait from Egyptian Hawara, encased in a double frame of sycamore-fig wood and bound with rope (Figure 4.19));Footnote 118 likewise, there are the odd second-degree glimpses of how such panels might have been displayed in certain contexts (as, for example, on the painted scenes adorning the inside of a second-century AD sarcopgagus from Kerch in the Crimea (Figure 4.20)).Footnote 119 In general, though, our understanding about pinakes and tabulae – that is, about their actual form, their surrounds and different modes of display – must derive in large part from the second-degree evidence of Campanian wall-painting itself. Of course, this has not stopped many classical archaeologists, intent on debating hypothetical ‘originals’ – and original framing practices.Footnote 120 But in forging my own brief response to the questions above, I want instead to revisit these issues from the perspective of Roman mural schemes themselves. For what strikes me as so revealing about the framed pinakes and tabulae of Campanian wall-painting are their playful mimetic games.

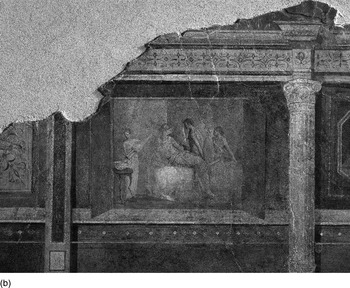

Figure 4.21a View of the east wall of cubiculum B of the Villa della Farnesina.

Figure 4.21b Detail of pinax painting from the same room.

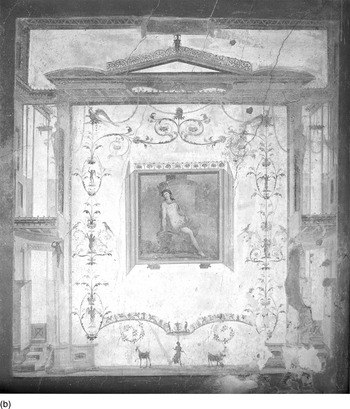

From this perspective, it is worth emphasising the various illusionistic tricks that Roman fresco-painters developed so as to render their two-dimensional walls in the guise of three-dimensional picture-galleries.Footnote 121 For one thing, ‘panel-paintings’ were frequently displayed within painted aediculae, following the architectural display strategies of actual pinacothecae (all the while rendering that architecture within the representational frame of the two-dimensional wall);Footnote 122 for another, such two-dimensional ‘galleries’ even sometimes rendered the physical casings of such panels, exploiting moulded plaster panelling and various chiaroscuro effects to capture the shapes of wooden pinax-surrounds as well as the imaginary shadows that they cast.Footnote 123 Most striking are the folding ‘doors’ frequently depicted on such paintings from the third quarter of the first century BC onwards, suggesting the wooden shutters of pinakes tethyrômenoi.Footnote 124 One revealing example can be found in cubiculum B of the Villa della Farnesina in Rome's modern-day Trastevere district (Figure 4.21a; cf. Figure 1.20).Footnote 125 The intricately adorned cubiculum toys with multiple make-believe means of ‘inserting’ fictive panel-paintings within its two-dimensional, painted mural space: these range from the architecturally framed central image of the north-east wall (its rich polychrome subject contained within a fictive aedicula structure), through the gilded white-ground panels to the side (supported by miniature siren-figures against a rich red setting),Footnote 126 to the two extant shuttable pinakes painted on top of the cornice in the room's side walls (the erotic scenes within thereby rendered perpetually ‘open’ to view (Figure 4.21b)).

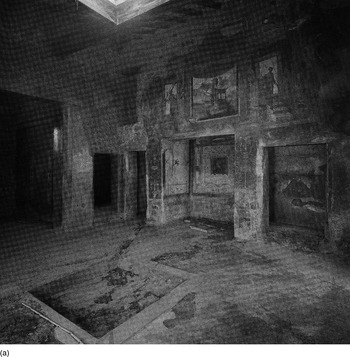

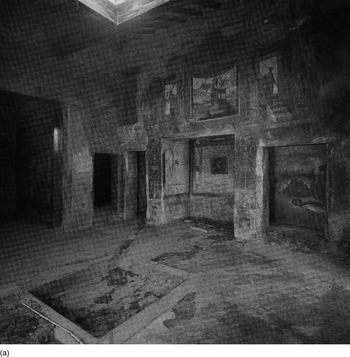

Illusionism, it seems to me, plays the decisive role in such installations.Footnote 127 Perhaps no case study demonstrates the point better than the atrium of the Casa dell'Ara Massima in Pompeii (VI.16.15).Footnote 128 In a (real-life) architectural alcove, receding back from the atrium's west wall (directly opposite the external entrance), we find a subject that was particularly favoured in the Pompeian home (Figures 4.22a–b):Footnote 129 a scantily clad Narcissus (with spear held in the left hand), reclines in three-quarter view before a pool of water; Narcissus’ reflected face – the celebrated cause of his mythological downfall – can be made out in the represented pool at the lower left-hand edge of the panel. The square panel is framed by delicate pattern (floral motifs, animals, even perching birds), framed in turn by the larger red mural scheme that engulfs the room (extending to include additional landscapes and architectural vistas in its Fourth Style upper storey (Figure 4.22a).

Figure 4.22a View of the west wall of atrium B of the Casa dell'Ara Massima, Pompeii (VI.16.15) (with view into the ‘pseudo-tablinum D’). Photograph by Michael Squire.

Figure 4.22b Detail of Narcissus panel in the recessed ‘pseudo-tablinum’ D off the atrium in the same house. Photograph reproduced by kind permission of the Archiv, Institut für Klassische Archäologie und Museum für Abgüsse Klassischer Bildwerke, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich.

What particularly interests me about this panel is its make-believe presentation as a pinax: observe the trompe l’œil shutters that leave the image ‘open’, as well as the two depicted supports below (Figure 4.22b).Footnote 130 In this case, the literal surrounds of this image go hand in hand – or frame in frame – with its metaphorical mounting of themes about replicative representation: just as Narcissus falls for his reflected image within the image, mistaking simulated image for objective reality, so too are viewers in danger of being duped by the fictive pinax within the two-dimensional reality of the wall. As is well known, the underlying stakes of the Narcissus story – its richness for thinking about the push-and-pull of pictorial representation – engrossed ancient thinkers, and none more so than the Elder Philostratus: enamoured with such questions, the Imagines inevitably turned to a painting of Narcissus, reframing it in relation to the author's own graphic project of ecphrastic representation.Footnote 131 Within the Casa dell'Ara Massima, it is the make-believe of wall-painting specifically that seems to have been at issue. In this connection, we might note an additional conceit, designed to replicate still further the underlying replicative games. For the lived-in space of the atrium itself frames this two-dimensional pinax: not only did the image of Narcissus (reclining before his pool) look out onto the room's central water-filled impluuium, but the fictive picture-frame seems originally also to have been displayed behind a basin of water below.Footnote 132 The result is a telling mise en abyme that at once mirrors and interrupts the frames of pictorial representation. For refracted in the rippling surface of real-life water, our fictively framed image of Narcissus (figured in front of his own reflected image) toys with the suggestive possibility of at once replicating and breaking the frame. We are dealing, in short, with different ontologies of reality and representation, each one sutured over the next: the theme of Narcissus’ own enthralment with a non-real image (as depicted within the painting's frame), the picture-frame itself (which plays with the make-believe of an actual pinax propped up on the wall), the framing space of the mural scheme that surrounds these, and the lived-in space within which all of the above are contained.

The illusionistic framing of this pinax in the Casa dell'Ara Massima makes for a poignant contrast with the one depicted in Alma-Tadema's gallery (Figures 4.1 and 4.2). Where Alma-Tadema's picture-frames demarcate the essential space of ‘art for art's sake’, Roman muralists seem to have surrounded the frames of wall-painting rather differently. At issue in Campanian wall-painting, once again, is a distinctive set of ontological questions. And ultimately, I think, these literal picture-frames interrogate issues about frameworks of pictorial mimêsis itself.

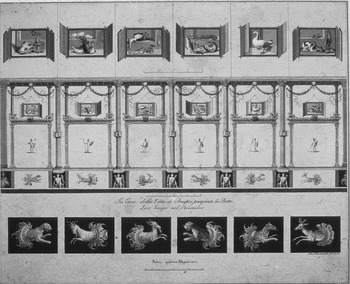

Figure 4.23 Reconstruction of the west wall of peristyle 39 of the Casa delle Vestali, Pompeii (VI.1.6) (by Giuseppe Chiantarelli (1803), from the Archivio dei Disegni della Soprintendenza Archeologica di Pompei).