11 - Reading the Consumed: Flayed and Cannibalized Bodies in The Siege of Jerusalem and Richard Coer de Lyon

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 May 2021

Summary

THE idea of flaying in the Middle Ages looms much larger in the mind and the literature than it seems to have in real life and law. Flaying as an answer to treason was the ultimate rejection, disassociation and erasure of identity and, as such, highlights the deeply culturally damaging acts for which it was used as a punishment. The crime of treason held particular power, being ‘as much a social as legal breach and one rooted in the viciousness of character’. In late medieval romance, such viciousness is often attributed to the enemies of Christianity, particularly Saracens. Flaying captured the imagination, and incidents of flaying are often moments of excessive, even fantastic, violence. As such, it should not be surprising that flaying appears in two examples of flamboyantly violent late medieval romance: the alliterative Siege of Jerusalem (hereafter Siege) and Richard Coer de Lyon (hereafter RCL). Both are found in the mid-fifteenth century manuscript British Library, Add. MS 31042, also known as the London Thornton Manuscript. However, in these fourteenth-century Middle English romances, flaying is performed by Christians invoking ‘in a single shocking image, the primitive significance of treason’, rather than by the Saracens against whom they fight and with whom such actions were often associated.

Flaying of animal flesh was commonplace in the Middle Ages. It has been applied not only in cooking, but also in parchment making, in the construction of the very connections we have to that moment: books. Medieval manuscripts themselves carry symbolic value just as much as the words on their pages. In the hands of a reader (or perhaps in the hands of a critic hundreds of years later), the manuscript can at once represent the immortality promised through salvation – the persistence of the body after death – while at the same time creating that message through a still-used piece of skin. Books offered the opportunity to connect flaying both with the animal itself and with salvation; the heart of the saved and the body of Christ are compared to a stretched animal skin turned to parchment. Sarah Kay notes that ‘flayed skin can be conceptually detached from the life that once was and serve, instead, as a means to immortality’

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

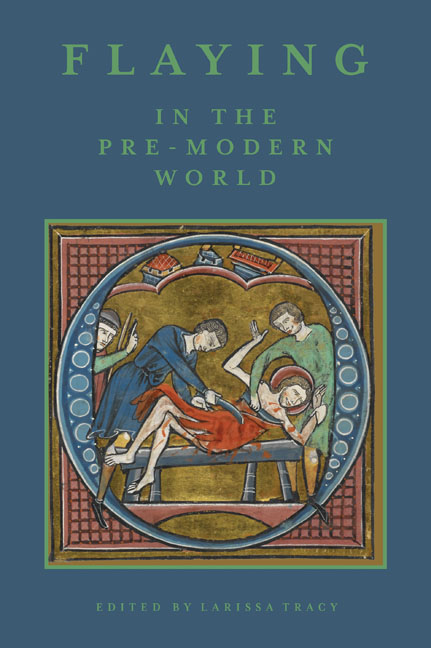

- Flaying in the Pre-Modern WorldPractice and Representation, pp. 285 - 307Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017