4 - Medievalism and the ‘Flayed-Dane’ Myth: English Perspectives between the Seventeenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 May 2021

Summary

THE fascination with the Middle Ages has a lengthy tradition which, arguably, began shortly after the period ended. For centuries the popular view of the age was based on the claim of the fourteenth-century Italian scholar Francesco Petrarch (1304–74) that the medieval period was one of literary and cultural ‘darkness’. Whereas the terms ‘medieval’ and ‘medievalism’ were first used in the nineteenth century to denote the intermediate period between the ‘classical’ and ‘modern’ eras of history, for centuries the post-medieval English fostered images of a ‘dark’ and ‘savage’ past to support the Petrarchan view of pre-Conquest England and the Continent. This anachronistic view has long been abandoned by scholars; however, the concept of the ‘Dark Ages’ became firmly established among English dilettanti and scholars alike, beginning in the Renaissance and reaching its height in nineteenth-century England, with some residual traces in the early twentieth century. This (often inaccurate) vision included a presumption of brutality and violent punishment meted out by a lawless populace. Early modern society, in particular, was convinced of medieval savagery, which they believed included flaying, castration and frequent use of torture. In the seventeenth century a myth involving a ‘flayed Dane’ – a pillaging Viking skinned by Anglo-Saxons – captured the attention of the English diarist Samuel Pepys, who first recorded it; from that point until the twentieth century, the legend of the ‘Dane-skin’ tacked to the doors of early medieval English churches persisted. The ‘historical reality’ of the myth is loosely rooted in an actual episode during the reign of King Athelred II (r. 978–1013 and 1014–16), but the myth itself is a chimera constructed through the conflation of events and the invention of ‘material evidence’ to support early modern claims of the barbaric and uncultured ‘Dark Ages’. Rather than providing evidence of an actual Anglo-Saxon practice of flaying sacrilegious Danes, or of displaying the flayed remains of hapless, massacred Danes, this myth perpetuates an early modern perception of medieval brutality and acts as nothing more than sensational modern nationalist propaganda.

In 1002 ce the Anglo-Saxons had for a decade been making regular payments called the Danegeld, while still living under the constant threat of attack from Vikings.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

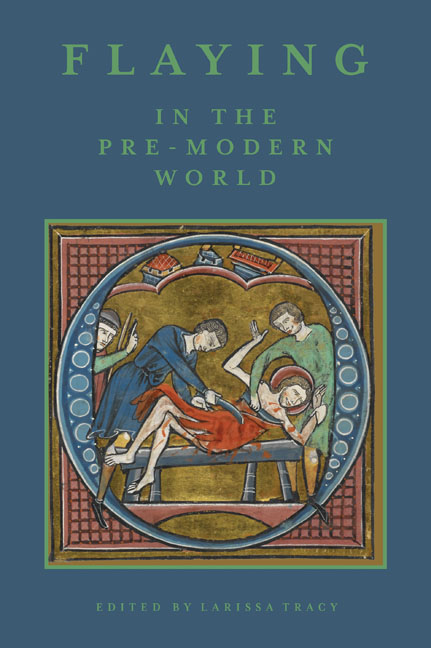

- Flaying in the Pre-Modern WorldPractice and Representation, pp. 91 - 115Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017