13 - Face Off: Flaying and Identity in Medieval Romance

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 May 2021

Summary

FEW forms of punishment are as brutal as flaying – literally removing the skin as a way of figuratively excising the crimes and the identity of the accused. Robert Mills explains medieval notions of skin as memory: ‘to flay someone alive would be to tear away the bodily surface onto which transitory memories and identities could be inscribed – only to fashion an etched parchment in its place (the dead skin), from which “timeless” moral lessons could be read’. Flaying is a prominent medieval literary and artistic motif, as this volume attests; it occurs frequently in a variety of texts across the geographical and linguistic span of medieval Europe. In medieval romances like Cligés, Havelok the Dane and Arthur and Gorlagon, flaying features as a form of punishment, threatened or inflicted in the course of legal procedure, legitimate or illegitimate. It marks not only the bodies of those whose skin is removed, but also the reputations and identities of those who remove it. As a method of judicial interrogation or punishment, flaying leaves lasting scars even if it is not fatal – it generally precedes further abuse and execution. In Havelok the skin of the criminal, Godard, is removed to erase the royal identity that he sought to bestow upon himself by taking it from Havelok. In Cligés Fenice's skin will bear the marks of her identity as an adulteress even as she heals and is reunited with her heroic lover. In Arthur and Gorlagon flaying is the fatal sentence for adultery and treason. Removing skin by flaying reveals a multitude of identities for the flayer and the flayed – tyrant or adulteress.

But skin removal is not always a form of judicial punishment. The Scandinavian, or ‘Viking’, fornaldarsögur – tales of mythical heroes equivalent to romances – Örvar-Odds saga (Arrow-Odd's Saga) [hereafter ÖO] and Egils saga einhenda og Asmundar saga berserkjabana (The Saga of Egil and Asmund) [hereafter EA] include flaying episodes where the skin is removed in the heat of battle or in the fulfilment of a quest; the resulting scars are identifying markers of supernatural difference, not criminality or sanctity.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

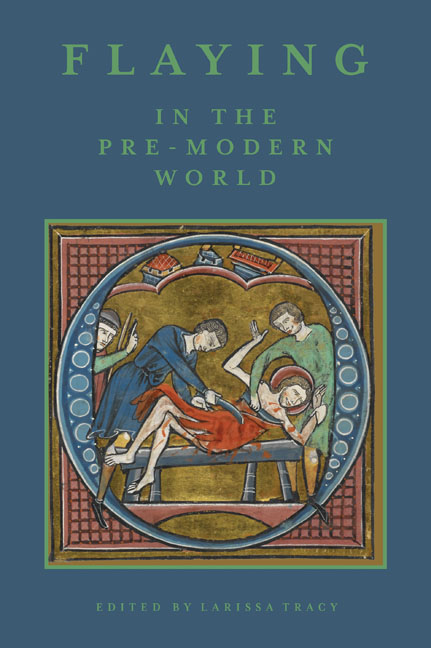

- Flaying in the Pre-Modern WorldPractice and Representation, pp. 322 - 348Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017