1.1 Dance as “Revolution”

The initial response to modern dance hardly suggested that it would constitute a cultural revolution. After performing in the homes of aristocrats and patricians in New York, London, and Paris, Isadora Duncan was engaged by Loïe Fuller for a tour in Central Europe; she soon went her own way, and in 1902 and 1903 gave public performances in Budapest, Munich, Berlin, and then again back in Paris. The response was mixed. One reviewer in Berlin commented that audiences had been enthusiastic, but “one really has to wonder why” because “Miss Duncan lacks not only shoes and stockings but also a few other things that her colleagues in the ballet have” – namely talent and technical ability. Duncan was clearly “no genius of the dance art.” Nor did she display any particular fire or “passion”; her performance was “prim” and suffered from “English sentimentality.” Another Berlin reviewer found Duncan’s performance “lovely, but academic and boring ... sweetly pretty” rather than powerful. A Dutch newspaper reviewer reported similarly in January 1903 that Duncan “takes things very much in earnest.” In March a Vienna paper reported that her dance appealed through its “gentle prettiness” and was a little “pedantic.” In June a Paris reviewer reported that her audience, “which is very fond of its ballet tradition,” had laughed at her histrionics. Late in the year a German theater journal called her “didactic virtue in motion ... this isn’t dance, it’s a lesson.... Her choreographic training is mediocre, and her temperament cool.” It was all very nice, but her chaste spirit was disquieting. Wasn’t the dance supposed to have something sensual at the back of it? By early 1904 another Vienna reviewer remarked that “This Miss Duncan,” with her “sweet, childlike demure eyes,” her “touchingly pretty face,” and her boring “skipping around,” was “starting to get on our nerves.”Footnote 1

And yet, by early 1904 the tide was turning. While dance critics were skeptical, most audience response was positive, and in some cases verged on the ecstatic. Duncan recalled in her memoirs that art students in Munich and Berlin were so excited they stormed the stage after numerous encores, or insisted on unharnessing the horses from her carriage and drawing her through the streets; taking her flowers and handkerchiefs and even scraps of her dress and shawl as souvenirs; carrying her off to a pub to dance on the tables; and carrying her back to her hotel in the morning. Her audience “came to my performances with an absolutely religious ecstasy.”Footnote 2 Most grownups were less euphoric; but newspaper reviews even in the initial months of Duncan’s stay in Central Europe were often at least moderately positive. In February 1903, for example, one Vienna paper praised her “well-measured, graceful movement” and her ability “literally to embody classical music” with “artistically refined sensuality”; another German paper reported of a performance in Vienna in March that at first her audience was uneasy with her unfamiliar movement idiom, “but then gradually they found her gentle grace pleasing.” Another Vienna paper reported the same process: Duncan’s performance was “so completely unexpected” that it took time for the audience to appreciate it; but gradually her “sincerity,” her “warmth, roguish charm and serenity,” and her “noble and restrained grace” won them over. In January 1904 a reviewer in Munich wrote that Duncan made a “highly charming and aesthetically enjoyable impression”; in March the same paper reported that applause for her dance to Strauss’s “Blue Danube” waltz rose to “a paroxysm.”Footnote 3

By the middle of 1904 Duncan had developed a growing momentum, and was increasingly perceived – and praised – as powerful and revolutionary, not just sweet and pretty. In June 1904 a Heidelberg paper reported that “yesterday slowly but surely this brave girl conquered her audience,” showing them that “dance is a great, chaste art.” By February 1905, a retrospective reflection in a German literary journal on the occasion of Duncan’s fiftieth appearance in Berlin reported that “after a spirited campaign of three years duration against critics, roués and wastrels, Isadora Duncan strides victorious and laughing across the battlefield.” Duncan was a “revolutionary” who had “brought her cause a decisive triumph.”Footnote 4

Duncan had been able to convince audiences that what she was doing was legitimately dance, and legitimately art. In doing so she cleared the way for the whole generation of young women who followed her onto the stage – many of them inspired specifically by her performances. How had Duncan accomplished this feat? She had clearly matured as an artist and performer. But more important, she was also a gifted businesswoman. As one Dutch reviewer put it already in January 1903, Duncan was “an American, gifted with a healthy portion of practical insight,” and had hit on a number of “outstanding advertising ideas.” By 1906, a particularly acute German observer remarked that “Miss Duncan is one of the most innovative phenomena in the world of the arts and business. Two souls reside in her pretty breast – the artist and the master of ‘business.’”Footnote 5 Whatever her artistic gifts and abilities, her contemporaries understood that Duncan had triumphed also, and perhaps above all, by developing a product and a marketing strategy that were perfectly suited to the specific conditions of her time and place. Those who emulated her would further refine the product and expand the strategy. Ultimately they succeeded in making modern dance not just a powerful emotional or spiritual experience for many in its audience, but also a lucrative performance form and even an important political and philosophical phenomenon.

1.2 Modern Dance, Modern Mass Culture, and Modern Marketing

As an exercise in product design and in marketing, the strategy of modern dance was shaped by a set of profound shifts taking place in the art market in the decades around 1900. Historians often refer to this as the emergence of a “mass” culture market. The term mass is used here in a very specific sense, indicating not just a quantitative change but also a qualitative change. The modern market as it emerged in this period was a “mass” market specifically in the sense that it was not segmented by class, region, or culture. “Mass” culture is neither the culture of the upper nor of the lower classes, neither “high” culture nor folk culture. It was first developed and remained centered in large cities; but its appeal was by no means limited to urban audiences and its geographic reach was in principle unlimited. Indeed mass culture was pan-regional and cross-cultural. Modern mass culture as it emerged in the late nineteenth century was increasingly global culture – just as mass culture is today. In short, “mass” culture ignores and erodes every form of structuring boundary between potential audiences. The entrepreneurs who organized it deliberately set out to draw large and socially mixed audiences – white- and blue-collar; men and women; urban, suburban, and rural; “respectable” and “advanced”; conformist and avant-garde. In doing so they built a cultural pattern that was structured fundamentally not by the loyalties, traditions, and identities of class, locality, region, religion, or even nationality, but by the market. Mass culture is commercial culture. That makes it protean and adaptive, rather than prescriptive: It measures its success not by its ability to reproduce particularly fine recapitulations of aesthetic tradition, not by its rootedness in a particular local or social setting, but by its innovative and therefore expansive capacity and by its mobility – as measured, ultimately, by sales.

The expansion of the mass culture market in the decades around 1900 was a result of a whole range of processes. Rising average incomes driven by the ongoing industrial-technical revolution raised average per capita incomes in Western and Central Europe by more than half between 1870 and 1910 (and doubled them in the United States), creating armies of consumers with some disposable income to spend on cultural products such as performances, publications, or images.Footnote 6 Rising literacy gave a steadily expanding proportion of the population access to the urban culture market. By 1900, every major European city had a kind of dual existence: one the real city, and one the city as portrayed in the mass daily press, which, with circulations in the tens and hundreds of thousands, was a critical source of cultural coherence and the decisive underpinning of the emerging culture market. Indeed, the daily press penetrated well beyond cities, informing – as one German skeptic put it already in 1889 – “almost every family,” including “the youth and the servants,” even in “the most remote corners of our fatherland” of what was going on in the great cities.Footnote 7 The growth of the mass labor union movement particularly from the beginning of the 1890s led to gains in working conditions, such as hours of work, giving a growing number of working people some disposable time. The expanding communications and transportation network played a critical role in creating a transnational cultural market, by making travel (particularly by train) incomparably faster, cheaper, and more frequent. But it also helped to homogenize the culture market locally by making it possible to concentrate cultural institutions – theaters, museums, music halls, shopping districts, amusement parks, cinemas – in particular locales, especially in the center of cities. Finally, in some cases particular technologies had a profound impact. The most obvious was moving pictures, which were first introduced in the late 1890s, and by 1914 were the single most popular art form in European societies. Another example was the phonograph, which revolutionized the consumption of music. Advances in lithographic and photographic reproduction transformed the consumption of images – giving rise, for example, to a wave of photographic pornography, the picture postcard, the illustrated newspaper, and the handheld Kodak single-lens reflex camera and mail-in roll-film development.

These changes brought with them profound transformations in patterns of cultural consumption. Commercial entertainment enterprises could now appeal beyond their neighborhoods and even beyond their cities, drawing on a vastly expanded and more socially diverse potential audience. By the 1910s, in many cases even rural people could travel to the nearest town or city to take in a movie or a show or go shopping. The rising importance of this mass audience gave a tremendous impetus to cultural forms that are now entirely familiar to us, but were quite new at the time – the advertising industry, the modern fashion industry, the custom of going shopping. In the latter case the transformation of the social role of women was momentous; the emergence of shopping in central business districts drew women out of their homes and neighborhoods and created what the historian Judith Walkowitz has called “heterosocial spaces” where men and women mingled, anonymously, in public.Footnote 8 This in itself undermined prevailing codes of gendered behavior and the gendered organization of society. In many cities, indeed before World War I, the police had a difficult time distinguishing women who took part in this emerging “heterosocial” world from prostitutes; a series of arrests of women out shopping in German cities in the late 1890s, for example, sparked major protests from German women’s organizations. But the mass market for consumer goods and entertainments undermined the traditional markers of class, as well. More conservative upper-class observers were horrified, for example, by the fact that young working-class men dressed up like people "better" than they were to go out on a Sunday afternoon, or by the “tendency toward addiction to fashion, vanity” and desire for “the greatest possible pleasure in life” among young working-class people who bought nice clothes and went out dancing, or to the movies.Footnote 9

Early modern dance was a creation of this new mass culture market. Its pioneering performers drew on a whole range of traditions and innovations to create a hybrid form that appealed across a range of cultural registers, and to a range of audiences – or rather, again, to a “mass” audience. The success of the form derived, in no small part, from the versatility that this synthesis generated. In multiple ways, moreover, modern dance drew quite specifically on the most dynamic new developments in the European culture market, turning them into highly effective and prestigious marketing channels that associated it with the cultural cachet of innovation and progress. In that sense, the term modern refers not just to the fact that this art form developed in the twentieth century, but also to the fact that it very self-consciously associated itself with the latest trends in politics, philosophy, marketing, and technology.

The modern dance synthesis operated, first, at the level of technique, drawing on and synthesizing three distinct movement traditions to create something that was at once familiar and new. Those traditions were variety-theater and vaudeville dance, a venue and performance form historically closely associated with the urban lower-middle and lower classes; ballet, an established if not terribly respectable part of the “high” culture of the social elite; and a system of movement training developed earlier in the nineteenth century by the French theorist François Delsarte, which was quite widely practiced particularly among the European and North American middle classes.

From variety theater modern dance took elements of “skirt dancing,” popular in variety theaters and music halls for two or three decades prior to the modern dance boom. Skirt dancing was a high-energy form involving various gymnastic moves such as high-kicks, backbends, splits, and so forth; the “can-can” was the most well-known later offshoot. Most of the early modern dancers had at least brief careers in skirt dancing before launching their own independent productions. Loïe Fuller and Ruth St. Denis, for example, performed for some years in vaudeville; but Isadora Duncan, too, worked first in popular theater.Footnote 10 Many of the European dancers, too, started out as variety theater dancers; and most of them continued to perform primarily in variety theaters in London, Berlin, and Paris. The extreme case was Gertrude Bareysen/Barrison, who had a very successful career as part of an off-color variety theater song-and-dance act (with her four sisters, who dressed up in baby clothes and sang suggestive songs) in Europe and the United States before becoming a successful “serious” dancer in Vienna in her twenties.Footnote 11

The emphasis in variety theater dancing was on high energy, acrobatic flexibility, and acting ability; and while modern dance only remotely resembled skirt dancing, all the modern dancers adopted and adapted these elements to one degree or another. This meant that modern dance was founded in part on a movement idiom that had an established appeal among lower-middle and working-class audiences.

Most of the modern dancers also, however, had at least some ballet training. Many of them vigorously denied that; but ballet was one of the dominant dance idioms of the period, and anyone interested in movement was exposed to it. A number of modern dancers incorporated at least some gestures or steps from the classical ballet into their acts. Grete Wiesenthal was unusual in having a first career in the Vienna opera corps de ballet; Ruth St. Denis took lessons from the famous ballerina Marie Bonfanti in New York; Antonia Mercé/“La Argentina” was also trained in classical ballet in Madrid before striking out on her own. In addition, by the 1900s a number of prominent European ballerinas danced both in ballet and opera companies and in variety theaters, particularly in London. In such venues they seem to have offered hybrid performances that showcased both the technical mastery of ballet and some of the crowd-pleasing energy of vaudeville dance.Footnote 12 Critics often observed that the modern dance pioneers had no real technique, and again, the performers prided themselves on that fact (even when it was not entirely true). But many of the modern dancers adopted some of the gestural language of ballet.

This was not the only element that helped to make the modern dance aesthetic accessible and legitimate to middle-class audiences, however. Most of the modern dancers had studied the movement training first created by François Delsarte in the mid-nineteenth century, and developed and propagated later by others, particularly in the United States.Footnote 13 By the late nineteenth century Delsarte movement was widespread among women of the upper and middle classes, in part as a form of training in comportment and gracefulness. The early modern dancers drew on Delsarte poses as well as on the rhetoric of “natural” movement and moral improvement that underpinned Delsarte’s system.Footnote 14 Both Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, for example, had Delsarte training and engaged early in their careers in a noncommercial, living-room performance form derived from it, often called “statue posing.” One London newspaper in 1908 even referred to Ruth St. Denis as “the latest exponent of the Delsartian school.”Footnote 15

1.3 Familiar Exotics

The modern dance synthesis operated also through dancers’ choice of themes – not only how they moved, but also what they portrayed by moving. They drew self-consciously on two fashionable aesthetic and cultural references already well established in the arts in Europe. On the one hand, they appealed almost compulsively to the authority of the classical Greek past. On the other, just as frequently they drew on the “seductive” charms of the “Orient” – a rather indeterminate cultural geography that included East and South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa.

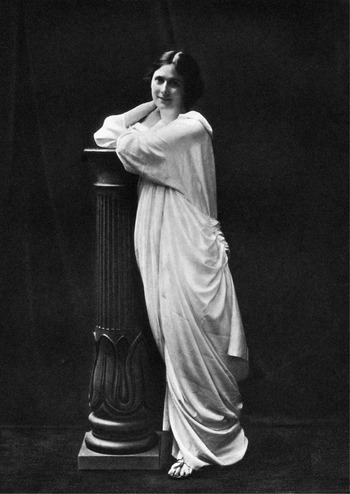

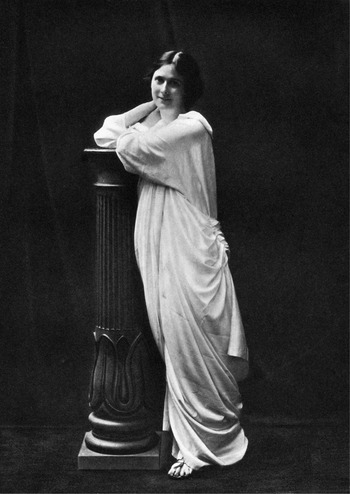

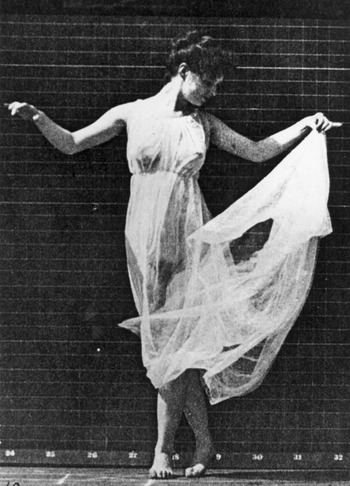

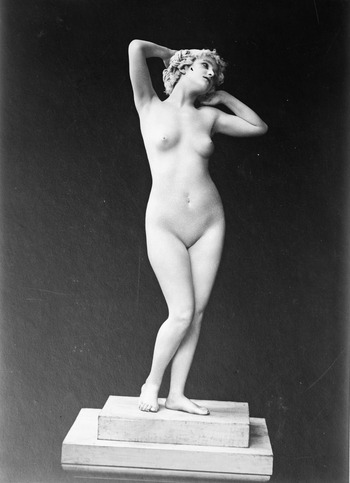

The reliance on classical Greek themes was particularly central in the early years of modern dance; and indeed Isadora Duncan wedded herself to the Greeks with extraordinary enthusiasm and tenacity. In her earliest independent performances in New York in 1899, she included readings from Theocritus (and Ovid) by her brother Raymond; at her first performances in London it was the young classics scholar Jane Ellen Harrison who read from Greek texts while Duncan danced. She returned again and again to this practice and point of reference.Footnote 16 She spelled out the connection between ancient Greece and modern dance most clearly in her address in Berlin in March 1903 on “The Dance of the Future,” a kind of manifesto of the modern dance movement. In that address Duncan invoked the Greeks as the authors of an art that was perfectly rational and universal, but also perfectly natural and individual. As “the greatest students of the laws of nature,” the Greeks understood that in nature “all is the expression of unending ever increasing evolution, wherein are no ends and no stops.” Greek depictions of dance – for example in statuary and in figures on vases – therefore suggested fluid, organic, dynamic movement. But the Greeks also understood that “the movements of the human body must correspond to its ... individual form. The dance of no two persons should be alike.” Her own dance idiom, derived from these principles, was therefore Greek (see Figure 1.1): “dancing naked upon the earth I naturally fall into Greek positions.”Footnote 17

Figure 1.1 Isadora Duncan Dover Street Studios

In fact, there was a certain deliberate confusion between dance and statuary in Duncan’s description of what she wanted to do. On the one hand, she claimed to have studied Greek art for endless hours – first in the British Museum and then at the Parthenon – in order to absorb and capture the wisdom and grace of ancient Greek movement. On the other hand,because Greek statuary captured the essence of that natural movement, her aim was to capture the essence of Greek statuary. “If I could find in my dance a few or even one single position that the sculptor could transfer into marble,” she remarked, “my work would not have been in vain.”Footnote 18 The references to Greek statuary in Duncan’s performances were so self-conscious that one critic accused her of offering mere “archaeological show-and-tell for upper-class girls,” while another observed that she “has something of the very winning and passionate devotion to beauty of a professor of archaeology.”Footnote 19 Others were more positive, exclaiming, for example, that she was “the Schliemann of ancient choreography,” for just as the archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann had rediscovered ancient Troy and created “restorations of ancient statues and palaces,” Duncan “restores, revives the ancient Greek dances.”Footnote 20

Other performers constantly drew on the same vocabulary, as did reviewers, promoters, and fans. A decade after Duncan’s debut in Central Europe, Tórtola Valencia too claimed to have spent “many hours in the British museum” in preparation for her dance career.Footnote 21 Karoline Sofie Marie Wiegmann, who would become one of the most influential exponents of the dance in Germany under the name Mary Wigman, offered a version of modern dance that, like Duncan’s, was in part inspired by portrayals of dancers on Greek vases – which she claimed to have seen not in the British Museum but in the Vatican.Footnote 22 Alexander Sacharoff, who performed solo in 1910–1913 and then formed a successful dance duo with Clotilde Margarete Anna Edle von der Planitz (Clotilde von Derp), discovered Greek art instead in the museums of Paris. His solo dances were so deliberately modeled on classical sculpture that one critic dismissed them as “museum art.”Footnote 23 One fan wrote to Maud Allan to praise her “essentially Hellenic spirit,” insisting that one was impressed by her “just as one is by a Greek sculpture, only that a living being is vastly more expressive than marble.”Footnote 24 Of Adorée Villany’s dances, one reviewer wrote that they were “based on a genuine archaeological foundation”; another found that she was “a Greek statue brought to life”; a third called her an embodiment, literally, of “the ethical culture of our humanistic education”; a French reviewer called her a “statue de chaire” – a statue made of flesh.Footnote 25 Ida Rubinstein was said to offer audiences “the exact equivalent of a gallery of antique statues.”Footnote 26 Another reviewer praised the “noble, calm beauty of classical Antiquity” that characterized Gertrud Leistikow‘s dance performances.Footnote 27 Tórtola Valencia, according to a particularly enthusiastic reviewer, was “like a marble [statue] animated by the gods, transformed into human flesh by a miracle of music”; another found that she embodied the “serene beauty of Hellenic rhythms” (as well as the “cosmopolitan elegance of the ‘music halls’ of Europe”).Footnote 28 Here too there was confusion between the real and the artistic image: One reviewer believed that Valencia had “brought back to her country in feminine flesh the perfect impression of those Oriental dances which, in the centers of the arts, are portrayed in marble sculpture,” a “human sculpture ... such as Praxiteles or Fidus [prominent German graphic artists close to the nudist movement] should see in their creative dreams.”Footnote 29

This classical Greek theme was important for modern dance for two reasons. First, classical Greece had quite extraordinary cultural cachet at the time, particularly among the upper and middle classes. Ancient Athens was widely understood to be the origin, pinnacle, and embodiment of Western civilization – of aesthetic refinement, political wisdom, and philosophical depth. Attitudes toward warlike Sparta were more ambivalent; but the Spartans were often depicted as the pinnacle of Western moral virtue – a society of disciplined, self-abnegating soldier-citizens unflinchingly devoted to the common weal, even unto death. Mastery of ancient Greek and Latin was still, in most of Europe, a marker of upper-class status – of education and refinement. One study of 1935 even referred in its title to the “tyranny of Greece over Germany”; and while the Germans were perhaps particularly enthusiastic, the myth of Greece as the cradle of Western Civilization was European in scope.Footnote 30

Ancient Greece was also identified as politically progressive, both because Athens was the model of republican civic virtue and because the ancient Greeks were still, in 1900, widely understood to have been rational and skeptical thinkers rather than superstitious religious fanatics. In some parts of Europe, in fact, the classical Greek tradition was portrayed as the antidote to later Europe’s own medieval fanaticisms of faith and belief. In appealing to classical antiquity, then, modern dance not only established itself as high culture, but also associated itself with liberal humanism and civic spirit.

Second, however, these associations were all the more important because in European culture at the time the dance was widely seen as not really a respectable art form. Because its medium was the body, dance blurred the line between the ideal and aesthetic, which were coded in European culture at the time as high, pure, good, and disinterested, and the merely corporeal or material, which were coded as low, dirty, sinful, and egoistic. The aesthetic theory codified by Immanuel Kant in the Critique of Aesthetic Judgment of 1790 had a powerful purchase on European thinking around 1900. The key distinction in Kant’s theory of beauty was between the (aesthetically) beautiful and the (sensually) pleasing. The latter is a perception of the value placed on an object by an observer who, in one way or another, desires it or its qualities; the former is a judgment based on completely disinterested, detached contemplation. The pleasing has “always a relationship to the capacity for desire,” whereas the beautiful is perceived by “pure contemplation (observation or reflection).” Whereas desiring a thing produces a state of inward dependence on it (because “all interest posits a need”), the appreciation of beauty is “a disinterested and free pleasure.” Appreciation of beauty also implies a claim to universality: Whereas the pleasing is pleasing in relationship to a particular viewer’s desires, appreciation of beauty is a pleasure of pure mind, pleasure in the object viewed or contemplated for its own sake.Footnote 31

In this code dance could only ever have a marginal position in the arts. As Friedrich Theodor Vischer put it his massive multivolume Aesthetics, or the Science of the Beautiful (1846–1857), dance focused on the “use of the living natural stuff” – that is, the body – “in a system of pleasing movements,” and therefore had a tendency to be “seduced” into offering “merely material titillation” rather than ideal values.Footnote 32 Vischer did not treat the dance as one of the arts: He merely discussed it briefly in an appendix, on pages 1,152 to 1,158 of his work.

To make matters worse, as a matter of social practice ballet and variety-theater dance were often regarded as, effectively, part of the upper and middle ranges of the sex market. This perception appears to have been rooted in reality, at least in some places: Grete Wiesenthal, for example, reported that while her colleagues in the Vienna Opera corps de ballet were not granted access to respectable bourgeois salons, they were assiduously pursued by “young and old aristocrats,” who as “worshippers” or “chivalrous friends” offered gifts and patronage in return for a more or less openly acknowledged sexual arrangement.Footnote 33 And the New York Times dance critic Carl van Vechten, who went to see variety-theater dance in London in 1907, “was more fascinated by the brilliantly caparisoned ladies of pleasure who strolled back and forth” in the back of the theater “than I was by the action on the stage.”Footnote 34 In France too, as the dance historian Ilyana Karthas has found, the ballet had become “primarily eroticized entertainment,” and public discussion of dance (e.g., in reviews) “catered to the male gaze, male desires, and male expectations by emphasizing dancers’ sensuality, personality, and physical appearance.”Footnote 35 As the dance historian Ramsay Burt has put it, then, “dancing and prostitution had for some time been established as characteristic forms of metropolitan entertainment.”Footnote 36

The result was not only that dance was not taken seriously as art, however, but even that anyone associated with it had to deal with a certain moral stigma. As the English sexologist and dance enthusiast Havelock Ellis put it in 1914, by the late nineteenth century “it became scarcely respectable even to admire dancing.”Footnote 37 Hans Brandenburg, who penned an early study of modern dance in 1912, recalled in his memoirs that “even close friends held my interest in the dance ... for a pointless frivolity,” while serious art critics told him he was “on the way to nowhere.”Footnote 38 When Maud Allan’s mother wrote the family lawyer for advice concerning her daughter’s intention to go into dance, he advised her that “a dance is a dance, and sooner or later it will be given in the Variety halls,” and then the “Church people” would be up in arms.Footnote 39 And one early American history of modern dance, published in 1912, recalled that just ten years earlier music pundits had experienced Isadora Duncan’s use of music from the European classical canon as “a desecration.” High art, like the music of Beethoven, Gluck, Schubert, or Mendelssohn, should not be associated with “so ‘primitive’ an art as dancing.”Footnote 40

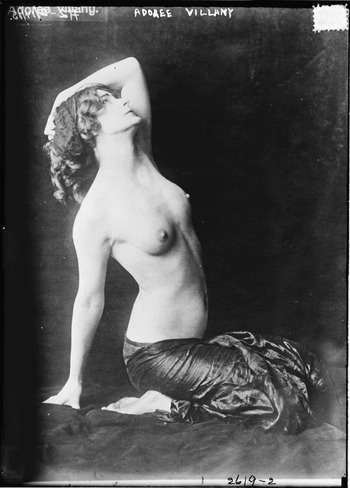

As the dance historian Iris Garland argues, then, the scholarly research in museums that the modern dance pioneers claimed to have undertaken and their evocation of classical sculpture was important because it “created an aura of cultivation, refinement and authenticity” for their performances. Deborah Jowitt is more blunt, observing that by “reminding her audiences of Greek statues, Duncan knew she was assuring them of the high moral tone of her dancing.”Footnote 41 Maud Allan played on this same cultural reference in an interview in 1908: Because her performances were “a serious and reverent attempt” to give expression in movement to the aesthetic qualities of classical sculpture, she claimed, “[m]y dancing is perfectly chaste" (see Figure 1.2).Footnote 42 And the German/American dancer Elizabeth Selden stated the case succinctly in 1935: “[T]he prestige of an approved and exalted past” helped to “get the dance rooted in many places that would otherwise reject that flighty art.”Footnote 43

Figure 1.2 Isadora Duncan’s chaste nudity, 1900

The word Allan used – chaste, in multiple languages – appeared over and over again in descriptions of modern dance performance; and so did countless variations of the claim that modern dance was not suggestive or sensual, but ideal, decent, respectable, inoffensive. In fact, as we have seen, at the outset many reviewers found the self-conscious “chasteness” of Isadora Duncan’s performances mystifying or boring; and some continued to find her annoying precisely because she was prim, proper, and asexual. The German painter Max Liebermann complained, for example, that Duncan was “too chaste for me.” Harry Graf Kessler found her sentimental and philistine, and felt that what made her attractive to the less discerning public was that “she is naked and conventional.” The English theater critic Max Beerbohm complained of Maud Allen that “I cannot imagine a more ladylike performance,” while a colleague called her “the English Miss in art.”Footnote 44

Ultimately, however, it became clear that this “chaste” quality was precisely the point. As Duncan put it in her address on “The Dance of the Future,” her aim was to achieve “a new nakedness, no longer at war with spirituality and intelligence” – a nakedness that was ideal, pure, and innocent, not gross, material, and sinful.Footnote 45 The idea that the (relative) nakedness in modern dance performance was not erotic nudity but authentic, “natural” nakedness – just like in Greek statuary – was absolutely ubiquitous in the discussion of the dance, ultimately becoming an outright cliché.

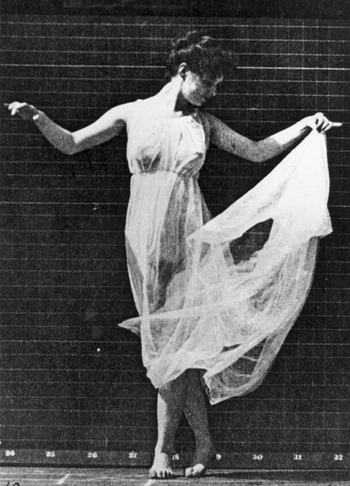

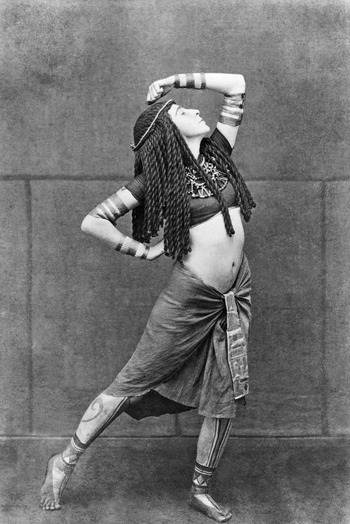

Already in March 1903, for example, one German reviewer assured readers regarding Isadora Duncan “that the nakedness of her legs, the veil-thin transparency of her dress make a highly respectable, even a pleasingly healthy impression.”Footnote 46 In December 1904 a St. Petersburg newspaper reported that “the nudité of her legs does not arouse sinful thoughts. It’s a sort incorporeal nudity.” Another found that the “barefoot girl shocked nobody, and her nudity was pure and imperceptible.” A third, in 1906, explained that Duncan was “undressed but not nude.”Footnote 47 One London newspaper observed of Maud Allan that “none but the most prurient could see the slightest appeal to any sense but that of beauty of motion and pose” in her dance, while another praised “its natural girlishness, its utter absence of sensuous appeal,” and a third believed that her “nudity was not intended to have an erotic effect.” A Hungarian critic even claimed that “during the dancer’s performance, I did not even think about her nakedness,” and the San Francisco Chronicle told readers in 1910 that “you scarcely stop to consider that she is a woman at all” because her performance was “the art of absolute beauty ... as modest as the sunrise, as chaste as the leaves of the forest and as sweet as the spring.”Footnote 48 One French reviewer reassured readers that Mata Hari’s performance was “very gracious and artistic and not at all pornographic”; another described her as “naked as Eve before she committed the first sin.”Footnote 49 Tórtola Valencia’s performance, “semi-nude, does not evoke the slightest shadow of eroticism.”Footnote 50 A reviewer of Anna Pavlova wrote in 1910 that in “the presence of art of this stamp, one’s pleasure is purely aesthetic. Indeed the sex-element ... counts for very little.”Footnote 51 One reviewer described Adorée Villany’s “absolutely chaste dances” as “completely free of any profane undertones”; another asserted that her “beauty stands far above any sweaty, torrid eroticism”; a third reported that “artistry is so great that when the final veil falls, the nakedness of her body is not disturbing even for a moment.” One Munich newspaper reported before her arrest there that

Hardly anyone will have been offended by [her performance]. For despite her complete nudity – or perhaps because of it – one did not even for a moment have the sense that this was indecent. One merely delighted in the blossom-like charm and wonderful expressive capacity of this graceful body.... The sight of her had the effect of a refreshing bath after a hot and dusty summer’s day.

After her arrest in that city on a charge of public indecency, another reviewer wrote that “the human mind was educated” by her performance “to see in nudity, in the end, something merely aesthetically self-evident" (see Figure 1.3). In a rather odd formulation, he concluded that “nudity was conquered by nakedness” (using the same word, Nacktheit, twice in one sentence).Footnote 52

Figure 1.3 Adorée Villany portrays grief, 1913

But while reference to the “ideal” art of classical Greece was central to the appeal of modern dance in its early years, again, this was not the only theme on which the modern dance pioneers drew. Isadora Duncan continued to focus her marketing message very explicitly on Greece; and most later modern dancers based some of their dances on Greek themes. But within a very short time a second set of archaeological and ethnographic references came to play an even more important role in modern dance: references to “Oriental” art. By 1906, Ruth St. Denis would build her tremendous success particularly in Germany almost exclusively on Indian themes, inspiring a raft of lesser imitators (see Figure 1.4). By 1907 Maud Allan was building a highly lucrative career primarily in England on her Salomé dance, that is on an ancient Hebrew (hence, at the time, “Oriental”) theme. Mata Hari’s career, mostly in France, was built on a mish-mash of Indian, Egyptian, and Javanese references. Elsa von Carlberg/Sent M’ahesa performed primarily “ancient Egyptian” dances (which she claimed to have derived from her study of Egyptian art in Berlin’s museums)(see Figure 1.5). Gertrud Leistikow performed what she termed Greek, Moorish, Japanese, Indian, and Egyptian dances, as well as “Women’s Lives and Loves in the Orient” and a dance of harem guards.Footnote 53 A special case was that of “Spanish” dance, as performed, for example, by Saharet/Clarissa Campbell, Antonia Mercé/La Argentina, or Tórtola Valencia. Because of the Moorish past, Spain was considered by many Europeans to be an outpost of “the Orient.”

Figure 1.4 Ruth St. Denis, Indian dancer, 1908

Figure 1.5 Sent M’ahesa, ancient Egyptian, ca. 1910

The use of Oriental themes built in particular on a distinctly less “chaste” and respectable tradition in European culture, appealing in particular to the taste for the spectacular, the exotic, and the suggestive. The Orient, as Europeans understood it, served that purpose well. Around 1900 Europeans commonly associated the Orient with opulence and luxury – probably an echo of the greater wealth and power of Middle Eastern and South and East Asian societies in the early modern era, and of the immense fortunes made by some Europeans in trade with Asia. The Orient was also associated with sensuality, sexual license, pleasure, and perversity; this was presumably an echo of earlier Christian prejudice against Islam, Hinduism, and other “Eastern” religions as immoral and lascivious. The Orient was further associated with mysticism and religion (a theme addressed in Chapter 4); but there was often a close connection in European minds between eroticism and the mystical and ecstatic, particularly in stereotypes of “Eastern” religion.

By the early nineteenth century, in any case, the “Orient” was no longer frightening or unsettling, having been domesticated by European economic dominance and the imperial experience. The conquest of a large portion of the Orient in the late nineteenth century – including Algeria and much of India already by the 1860s, and Egypt, Burma/Myanmar, and Vietnam in the 1880s – contributed to a widening awareness of the cultures of those regions in European culture.

In fact, in the last two decades of the nineteenth century a growing number of performers from various parts of “the Orient” showed up in the West, performing in variety theaters and also at the world’s fairs. The Paris fair in 1900 in particular appears to have been an important moment for modern dance: It was, as one observer put it, “nothing but one huge agglomeration of dancing,” including Turkish, Egyptian, Cambodian, Japanese, and other non-Western performers, among them Sada Yacco, who influenced many of the modern dance pioneers.Footnote 54 For the most part such performances were primarily of ethnographic interest. But Europeans soon developed their own dance acts that combined costumes and some of the movement and gestural vocabulary of “Oriental” dance with more familiar elements. A good example is Cléo de Mérode, a Paris opera ballerina, who made a hit at the World Exposition of 1900 with a “Cambodian” dance copied from a bona fide visiting Cambodian dance troupe; another is the dancer and courtesan Liane de Pougy, who appeared as a “Hindu priestess” in variety theaters in 1901.Footnote 55

By 1900, in other words, modified forms of Oriental dance idiom were only nominally “exotic”; in practice, they were very familiar. The (allegedly) Indian elements in St. Denis’s dance, the “Egyptian” ones in Sent M’ahesa’s, or the “Moorish” ones in Tórtola Valencia’s were not innovations; they played on the well-established craze for all things Oriental in this period. Already by the early nineteenth century, Oriental themes had been important in European ballet, opera, vaudeville, and variety-theater entertainments; they became more so with the onset of the New Imperialism from the 1880s until World War I.

Modern dancers drew on “Oriental” themes in effect as a counterpoint to “classical” themes, establishing a productive, dynamic tension. They used Greek references to communicate the Apollonian – the rational, harmonious, balanced, and ideal. As Duncan put it, “In no country is the soul made so sensible of Beauty and of Wisdom as in Greece,” and “The true dance” – Greek dance – “is an expression of serenity.”Footnote 56 The Orient they used instead to communicate the Dionysian – wild, emotional, sensual, sexy beauty, not wisdom but passion, not measure but appetite.

A particularly good example is that of Adorée Villany. Villany did perform in “Greek” mode; but a number of her dances were themed around particular intense and often negative emotions – grief, despair, melancholy, rage, jealousy, fear. In these more emotionally expressive dances, she often cast herself as an “Oriental” – an ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, Persian, or, in her own version of the Salomé act (including a recitation from Oscar Wilde’s play, in the French original), an ancient Hebrew. These figures permitted her, according to contemporary cultural stereotypes, to embody the passionate and the sensual. Reviewers reported, for example, that her performance of Wilde’s piece effectively portrayed “raving eroticism” or “the character of a wild-cat, the perverse woman’s combination of lust and cruelty”; that her portrayal of passionate, uncontrolled eroticism was a “significant histrionic achievement”; or that she portrayed “the inner feelings of the passionate Oriental woman.”Footnote 57

Villany was, then, able to use references to ancient cultures to combine in her performances, as one reviewer put it, “wonderfully soulful gracefulness” with “passionate expressive capacity” – the best of both worlds.Footnote 58 She was both a wild, out-of-control, active, perverse Oriental and a poised, balanced, static Greek, both unadorned ideal nakedness and (semi-)costumed Oriental exotic. Villany sought – apparently with some success – to embody what Kenneth Clark, in his classic study of The Nude in Western art, saw as the two divergent versions of the nude: the Celestial Venus, symbolizing divine, universal, ideal beauty; and the Earthly Venus, symbolizing carnal, individual, and sensual beauty.Footnote 59

Villany was anything but exceptional in this respect; other dancers in the period adopted precisely the same strategy. The low point was surely an advertisement for Maud Allan’s early London performances that billed her as “a delicious embodiment of lust” and described her “satin smooth skin” with its “tracery of delicate veins that lace the ivory of her round bosom,” her mouth “ripe as pomegranate fruit, and as passionate as the ardent curves of Venus herself,” and “the desire that flames from eyes and bursts in hot flames from her scarlet mouth” – and yet also billed her as “the breathing impersonation of refined thought and deified womanhood.” Reviewers responded by praising not only her “utter absence of sensuous appeal” but also her “nudity expressive, vaunting and triumphant”; or her ability to exert a “fascination ... animal-like and carnal ... hot, barbaric, lawless” but the next moment be “pure as the hilltop air.”Footnote 60 Mata Hari, too, was described as displaying both “wild voluptuous grace” and “true antique beauty”; in Tórtola Valencia’s case it was “wild abandon” and “stateliness.”Footnote 61 One of only two male dancers who inspired similar enthusiasm in this period, Vaslav Nijinsky, was not exempt; he too could be both “a Greek god” and “the embodiment of lust.”Footnote 62

Ruth St. Denis played on this dualism perhaps most furiously of all. In her signature dance she impersonated Radha, the consort of Krishna, awakened from motionless contemplation to enjoy each of the five senses in turn (hence the alternative title, “Dance of the Five Senses”) in a devotional dance that ended in an almost openly orgasmic paroxysm of sensuality, before returning to devotional immobility. As one early history of the dance reported it, during the dance she wreathed herself with flowers,

drawing them luxuriously around her, crushing them against her shimmering flesh ... satin-petalled lotus, laid in turn to her cheek, her arm, her lips; while the smooth ripples of muscles under her glossy skin respond with shivers of sensitive sympathy to the caressing pressure of her foot upon the ground. Every nerve is sensitive and in turn conveys the message.Footnote 63

Yet St. Denis set this suggestive and sensual dance in the context of a religious rite in a temple. As the Austrian poet, playwright, and critic Hugo von Hofmannsthal put it, St. Denis’s dance “goes right up to the borders of lust, but is chaste”; Harry Graf (Count) Kessler admired St. Denis’s ability to combine “animal beauty and mysticism,” both “sexless divinity and merely-sexual woman,” both the “sexlessness” of the American woman and the “almost animal sexual feeling of the Oriental woman” – as well as remarking, of course, that she appeared “as if climbed down from a Greek vase.”Footnote 64

At the turn of the century “animal” sensuality was widely associated in the European social elite not only with the Orient but also with the lower classes – so much so, for example, that some early scientists of sex just after 1900 assumed that sexual perversions were particularly common among Muslims, “primitive” peoples, and the working classes.Footnote 65 Not surprisingly, therefore, “Oriental” modern dance was often seen as appropriate for the variety-theater audience, while “Greek” modern dance was more tasteful. To some extent dancers conformed to this prejudice: The “Greek” Isadora Duncan, for example, very demonstratively refused to perform in variety theaters, while the “Orientals” Ruth St. Denis and Maud Allan performed primarily in them. Adorée Villany is, again, a particularly striking case: After being tried for indecency in Paris in early 1913 for performances in a rented theater, she moved to the Folies-Bergères, the leading variety theater in Paris, and danced on unmolested – still, as one wag put it, “almost nude” but “very chaste.” As one German language newspaper in Paris commented, it appeared that the Philistines of Paris were happy to tolerate immorality in popular entertainment, as long as it didn’t claim to be art for the elite.Footnote 66

And yet, the interest in things Oriental was at least as common among the middle and upper classes as among the working classes, and no less in high art than in mass entertainment. Oriental themes were common in European painting, theater, literature, opera, architecture, and ballet from the early nineteenth century onward. St. Denis’s “Radha” dance, for example, was performed to music from Leo Delibes’s “Oriental” opera Lakmé of 1883.Footnote 67 And collecting Oriental art was among the fashionable pastimes of the wealthy throughout the century. A striking case example of the convergence of modern dance and upper-class interest in the “Orient” is Mata Hari’s debut in Paris in 1905, which took place in the private Musée Guimet. Émile Guimet was an industrialist who had traveled to Asia and the Middle East in 1876, at the behest of the Ministry of Public Instruction, to study Eastern religions and buy up Asian and Islamic art.Footnote 68

As St. Denis’s use of opera music for her “Indian” dance suggests, an important strategy for rendering Oriental themes more respectable and hence appropriate for middle-class audiences was the use of European music as accompaniment not only for Greek dance but also for dances that played on Oriental themes. That reassured audiences that such performances were serious art, not frivolous (and morally questionable) entertainment. In some few cases where they wanted something more audibly “Oriental,” these performers commissioned music or even hired bona fide “Oriental” musicians. Both Ruth St. Denis and Mata Hari, for example, hired the Indian musician Inayat Khan and his ensemble to play for some performances.Footnote 69 For the most part, however, the modern dance pioneers simply ransacked the canon of great European composers for music. In particular, they appear to have relied heavily on the romantics and on the more lush of contemporary composers. Both Greek and Oriental dances were performed to the music of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Schubert, Liszt, Chopin, Wagner, Strauss, Delibes, Bizet, Debussy, and Brahms; less common choices were Sibelius, Tchaikovsky, Grieg, Satie, Milhaud, and Mussorgsky. Classical and baroque composers (Gluck, Händel, Bach, Scarlatti, Couperin) came a distant second; and non-Western music was the exception.Footnote 70

It is worth remembering that there were plenty of options at the time – tango, folk tunes, jazz, music-hall tunes, or authentic African, Near Eastern, East Asian, or South Asian music. But the overwhelming impression given both by reviews and performers’ own accounts is that dancing to the European romantics and moderns was effectively self-evident. Part of the appeal of early modern dance appears to have been that these performers sought to “embody” the romantic musical tradition – which we might see as a striking example of the translation of a nineteenth-century “high” cultural form for twentieth-century “mass” audiences.

The agenda of the modern dancers dovetailed neatly here with that of the variety theaters they performed in. Variety theater was widely understood to have originated as lower-class entertainment, and to be less than fully respectable. In London in particular there had been a major effort by morality campaigners to shut down variety theaters as dens of vice. In response to such campaigns and to the evolution of the more integrated, cross-class “mass” audience for commercial entertainments, metropolitan variety theaters were by the turn of the century deliberately moving away from their lower-class origins and catering to a “family” – that is, respectable – audience, including both men and women and members of the middle class, and to more established artists as well as the bohemian avant-garde. Variety theater in Germany and France passed through a similar development in the same years.Footnote 71 Modern dance performers were clearly part of this development: In place of the suggestive skirt-dance routines of the 1880s and 1890s, in the new millennium they offered a dance form that was identifiably “artistic.” Maud Allan’s extraordinarily successful engagement at the Palace Theater in London, for example, was a deliberate response to the middle-class moralists’ success in forcing the theater to abandon nude “statue posing” acts; after her the theater recruited the great ballerina Anna Pavlova for the same purpose.Footnote 72

Both the technique and the thematic content of early modern dance, then, were tailored to meet the needs of a culture market undergoing rapid transformation around the turn of the century. Where ballet had been coded as “high” culture for the middle and upper classes, and skirt-dancing or various forms of nude posing as “low” culture for the popular variety theater, modern dance was built to appeal to a “mass” audience in which such distinctions were increasingly irrelevant.

A special case of this kind of appeal was the participation of some of the modern dancers in a new kind of spectacular middle-brow entertainment that combined dance, music, and theater for giant “shows” with high production values and wide audience appeal, under the direction of well-known impresarios. In Europe, the most remarkable case was that of Max Reinhardt, who mounted major productions in – among other cities – Berlin, London, Paris, and Munich. Grete Wiesenthal took part in major Reinhardt productions in 1909, 1910, and 1912; Tórtola Valencia performed in multiple Reinhardt productions in London, Paris, and Munich between 1908 and 1912; Clotilde von Derp was in Reinhardt shows in Munich in 1909 and in London in 1911.Footnote 73 In the United States, the productions of David Belasco played a similar role; among others, Ruth St. Denis appeared in some of his productions early in her career.Footnote 74 Such programs achieved a broad middle- and lower-middle-class audience. They were an important vehicle to audience acceptance and stardom for many of the modern dance pioneers.

The modern dance pioneers were sufficiently successful in making their art “respectable” that a number of them also were able to vault themselves directly into the realm of “high” art, and to appear, for example, in some of Europe’s leading opera houses. Isadora Duncan choreographed dance scenes for the 1904 production of Tannhäuser in Bayreuth. Ruth St. Denis performed a number of her dance compositions during intermissions of some productions at the Comic Opera in Berlin in 1906, and Mata Hari danced in opera productions in Milan and Monte Carlo.Footnote 75 A number of dance stars adopted, too, another marketing strategy that allowed them to gain access to respectable theater audiences: renting legitimate theaters for solo appearances for periods of a few days or a week, and inviting “select” audiences – often the local arts community – to “private” performances. Such performances were not always uncontroversial; Maud Allan, for example, was prevented from performing in theaters in Munich, Vienna, and Manchester, and Adorée Villany was tried in Munich and Paris, obliged to wear a bodysuit in Vienna, and prevented from performing in Prague.Footnote 76 But the modern dancers were clearly successful in eroding the fairly rigid boundaries of the “respectable.”

1.4 Beyond Dance

In all these respects, then, the modern dance pioneers were able to achieve a synthesis that appealed to audiences across the whole spectrum of theater venues – from opera down to variety theater. Beyond that, however, many of them were able to move from theater into entirely new forms of performance, and new marketing channels, that were rapidly becoming characteristic of the twentieth-century mass consumer market.

The single most important of these was the cinema. The movies were largely understood to be primarily a lower-class entertainment form, a kind of poor-man’s theater. In fact film played a role in variety theater, where the short clips typical of the early film industry fit into the program well. But the market for the movies was soon clearly a “mass” market, crossing class boundaries; and that made it an ideal vehicle for the modern dance stars. The association of dance with cinema can be traced back to the beginning of both, when Thomas Edison made a two-minute film of Ruth St. Denis in 1894, or when an early French film company filmed Cléo de Mérode in 1900. But virtually every major and many minor dance stars appeared in film, with participation rising particularly after 1912 – including Grete Wiesenthal, Friderica Derra de Moroda, Rita Sacchetto, Gertrude Leistikow, Stacia Napierkowska, Saharet, and Olga Desmond.Footnote 77 There was a clear thematic connection between early film and modern dance, in that filmmakers too often played on the same themes that modern dance did, and for the same reasons. Some early German titles included, for example, “Sculpture Works,” “The Rape of the Sabines,” and, of course, “The Dance of Salomé”; and in 1913 Grete Wiesenthal starred in a film that offered “intimate scenes from the harem, which otherwise remain veiled from Europeans eyes.”Footnote 78 But even aside from such connections, of course, the alliance between dance and film was an obvious one: Dance was the art of movement, and the moving pictures were the logical means for dance artists to extend their reach beyond the theater audience.

There was, then, an important “comarketing” arrangement between the movies and modern dance. Film offered the dance stars another income stream; using dancers helped to give the movies a certain aura of raciness, by presenting moving images of beautiful, partially clad young women. But it also helped to give cinema a certain cultural cachet as the only medium that could fully capture and preserve a new, exciting art form.

The modern dancer’s use of still photography played on precisely this same ambiguity. Most of the early modern dance stars marketed still photographs of themselves. In some cases these were sold as cheap picture postcards; in others they were sold as relatively high-priced “artist’s studies.” In either case they were part of a new genre generated by the falling price of photographic reproduction, one that occupied a place midway between what we would today consider soft-core porn and a serious resource for artists, for whom the cost of paying models could be considerable. Isadora Duncan took a relatively restrained and high-brow approach, having her photo taken by the progressive and feminist Elvira photo atelier in Munich. Adorée Villany, in contrast, marketed large numbers of photographic images of herself in various states of undress, from fully wrapped up in black cloth (Chopin’s “Funeral March”) to completely naked (Mendelssohn’s “Spring Song”). These images were sold at her performances, at ticket outlets, and in other outlets in cities where she was performing. The Italian-German dancer Rita Sacchetto, Gertrud Leistikow, and Maud Allan used a similar marketing strategy, though their photographs were less daring.Footnote 79

Critics of the form regarded the sale of such images as clear evidence of merely prurient interest. In fact the development of the picture-postcard industry (and related forms of image marketing, such as collectible images sold in packs of cigarettes) had given rise to considerable debate about the artistic merits of mass-reproduced artworks. Some argued that even great artistic nudes or scenes from mythology in this form constituted pornography, not art; others argued that this was a way of bringing art to the masses. But whether the one or the other, for some performers such as Villany they were apparently a not-insignificant source of income. We can see this, too, as a form of comarketing arrangement with a rapidly expanding new cultural industry.

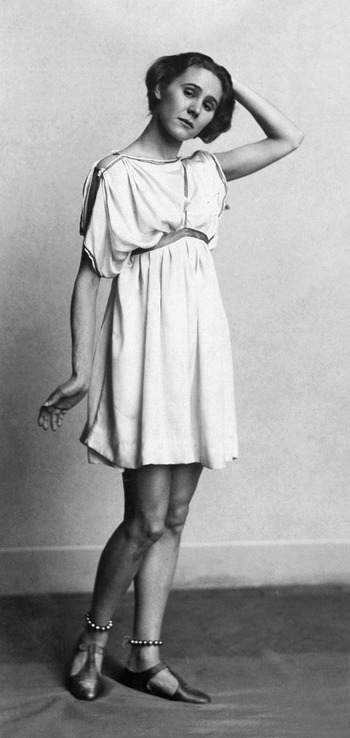

While modern dancers’ participation in the film and photographic industry appealed primarily to a lower-class audience, their participation in the burgeoning fashion industry placed them squarely in the context of middle-class culture. The modern dancers played an important role in the establishment and propagation of a new conception of female beauty, and of the clothing built around it. One of the odder aspects of the modern dance revolution was the importance of skinniness to reviewers, audiences, and even performers. In early reviews, for example, Duncan was a “maiden” or “girl,” or a “pale slender American girl.”Footnote 80 Mata Hari was slender and “snake-like” or “serpentine.”Footnote 81 Grete Wiesenthal was described by one critic as “a little maiden, skinny, even haggard.”Footnote 82 Anna Pavlova was “thin as a skeleton and her ugliness is off-putting”; or, in a slightly more charitable key, “neither beautiful nor specially well-built, but thin.”Footnote 83 Ruth St. Denis attributed part of her success in Germany in 1907 and 1908 to the “amazement of the German mind at seeing so slender a body.” One critic called her “exquisitely slender.”Footnote 84 Maud Allan was “slender” or “slender and lissome” or a “slender deer.”Footnote 85 Other dancers were described as “youthfully slender,” “sapling-slender,” slender like a birch-tree, or an eel (see Figure 1.6)Footnote 86

Figure 1.6 The slender young Grete Wiesenthal, 1908

The endless repetition of such terms seems a little obsessive and creepy to the modern mind; but to the attentive reader it reveals the almost subconscious impact and importance of the way in which the modern dancers were rethinking femaleness – from the foundation up, from a reimagining of female physicality.

We will return to this issue in Chapter 2; for now what is important is that the modern dancers formed another and very important comarketing arrangement with some of the leading fashion designers of the period, who built on and helped to cement an important shift in perceptions of what women’s bodies could and should be like. America was the original home of the ideal of slenderness; but European fashion played a crucial role in articulating the new ideal of female beauty after 1900.Footnote 87 Of particular importance were the French designer Paul Poiret and the Spanish/Italian designer Mariano Fortuny; and both had close working relationships with prominent modern dancers. Isadora Duncan and Poiret were close friends, and threw extravagant parties in each other’s honor in Paris once Duncan settled there. Poiret designed dresses for her, as well as for the Russian dancers Ida Rubinstein and Anna Pavlova. Duncan and a number of other performers wore Mariano Fortuny’s signature garments, which not surprisingly were modeled on Greek statuary and “Oriental” designs. His “Delphos” dress and the “Knossos” shawl were particular favorites of the modern dancers.Footnote 88 Ruth St. Denis modeled the latter at a kind of combined fashion opening and dance performance at the great Wertheim department store in Berlin in 1907; and some version of the “Delphos” was used variously by Duncan, Wiesenthal, St. Denis, and others. In the 1920s the great American dancer Martha Graham, among others, would wear Fortuny creations. Rita Sacchetto played a similar role for Poiret, modeling his clothes in Paris.Footnote 89

This alliance with fashion designers was a brilliant marketing move for modern dance because it helped to make modern dancers models not only for clothes, but also for an entire new style or mode of feminine physicality. As the designer Erté remarked of the very skinny Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein‘s influence on Paris fashions in 1913, fashion “dictates not only the color of hair and complexion but also the shape of the body.”Footnote 90 Becoming co-arbiters of that new code of beauty gave the modern dancers a claim to be vehicles of a profound kind of cultural authority.

It is, of course, hard work creating the kind of body that the modern dancers “demonstrated” – trim, strong, graceful, and well cared for. It should not be surprising, therefore, that some also launched themselves into the self-care industry – into cosmetics and the fitness and diet market. An extraordinary case is that of Olga Desmond (real name Sellin), a Polish-German performer who made a major splash in London in 1906 by taking part in a statue-posing act, and then in Berlin with a dance routine presented at “beauty evenings” in Berlin (see Figure 1.7). Desmond’s performances were highly controversial, and in fact in early 1909 were even debated in the Prussian state parliament.Footnote 91 But that notoriety was outstanding advertising. Over the following few years, Desmond sold photographs and postcards of herself performing her nude dances; made a short film; opened a dance school and attempted to open an Academy of Beauty and Physical Culture; performed in variety theaters around Germany and in St. Petersburg and Vienna; and marketed a massage apparatus, a soap, a beauty cream, a breast-enhancement cream, a cream to prevent freckles, and a book of beauty tips. During and after World War I she wrote an autobiography, published a system of dance notation, got into the movies, published a how-to manual on healthy living and fitness titled “The Secrets of Beauty,” and marketed a fitness apparatus involving large rubber bands attached to the feet and waist (the “Auto-Gymnast”).Footnote 92

Figure 1.7 Olga Desmond’s “Beauty Evening,” 1909

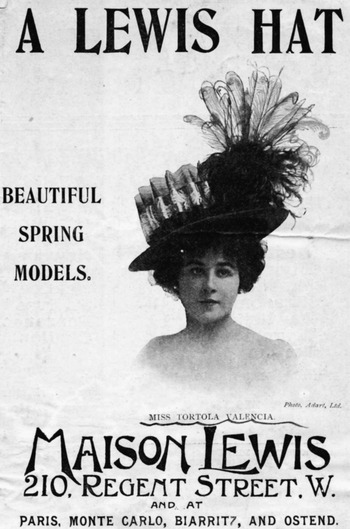

Desmond was an extreme case of multichannel marketing, but by no means unique. Tórtola Valencia, for example, was for a time the advertising face for a number of products of the French cosmetics company Myurgia (particularly the perfume “Maja,” but also bath salts and other self-care products). Her image was also used by the Louis Roederer champagne company; a British hat manufacturer (see Figure 1.8); “Mr. Seymour Churchill, the Greatest Authority on Feminine Beauty in the World” and merchant of beauty tips; and, perhaps ironically, a corset manufacturer. She also choreographed for other dancers; made and sold oil paintings of herself; sold photographs and postcards; and starred in films (A Woman’s Heart in 1913, The Struggle for Life in 1914).Footnote 93 Clotilde von Derp modeled for fashion designers, photographers in Munich and Paris, the school where she studied dance, and a German designer of dance clothes; her photograph was used in advertising for the dietary supplement Lebertran in Japan and for the Fiat automobile company in Europe.Footnote 94 Anna Pavlova endorsed a cold cream and a mouthwash, and a brand of silk stockings named after her.Footnote 95

Figure 1.8 Tórtola Valencia in an advertisement for fashionable hats, ca. 1910

In all these ways, the modern dancers were tapping into the new mass market for consumer goods, and into the new mass media. A very important part of the mass-market appeal of modern dance, however, was its association as well with the social elite – the aristocracy and the business and financial elite. And here too, modern dance achieved a remarkable degree of success. Among the European and American social elite, the modern dancers were in demand as performers at private salons and parties, as embodiments and proofs of the sophistication and “advanced” ideas of the wealthy, and in some cases as sexual partners. Among their other accomplishments, in short, the modern dancers also established themselves as a luxury commodity.

This connection was established very early. An early handwritten biographical sketch of Isadora Duncan reported that even in her early teens she had taught dance to “all the wealthiest children of San Francisco” at the home of the “wealthiest woman” in the city. She danced at private parties for some of the cream of New York society – including Astors, Vanderbilts, and Palmers – before leaving for Europe; before her departure, her name appeared most often in newspaper accounts of private parties at the summer homes of the New York plutocracy.Footnote 96 In London she gave similar performances at prominent citizens’ houses. Various French aristocrats helped to launch her in Paris, including the novelist, poet, and leading salon host the Countess de Noailles; the Countess de Greffulhe; and the influential music patron Winaretta Singer, Princess (by marriage) de Polignac and heir to the Singer sewing-machine fortune. At their parties, she met luminaries such as the composer Gustave Fauré, the lawyer and future president of the French Republic Georges Clemenceau, and the sculptor Auguste Rodin. When she opened a school of dance in Berlin in 1906, she appealed to wealthy patrons through a benefit concert selling tickets to members of the Imperial Court, the high nobility, and residents of Berlin’s central high-rent Tiergarten district (home to various villas and embassies) for up to 1,000 Marks, which was about a year’s salary for an industrial worker. One theater journal reported that “in fact a number of ladies from these circles have laid a thousand Mark note on the altar of Greek dance art.”Footnote 97 When Duncan’s sister Elizabeth reopened the school in Darmstadt in 1911, under the patronage of the Grand Duke of Hessen, there was one gift of 40,000 Marks and eight of more than 5,000, and a consortium of three wealthy donors guaranteed a loan of 200,000. In the meantime, plans launched by the Duchess of Manchester to help Isadora start a school in Britain, or perhaps in Scarsdale, New York, fell through. Short of money for her many projects, Duncan repeatedly remarked that “I must find a millionaire!” The millionaire duly appeared in the form of Paris Singer, brother of the Princess de Polignac and co-heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune, who saw her perform in 1909 and was immediately smitten.Footnote 98 In short, Duncan’s multifarious and varied – and carefully cultivated – connections with the American, European, and ex-patriate American social elite played a critical role in her entire early career.

The patronage of the social elite was almost equally important for Ruth St. Denis. The architect and art patron Stanford White played a role in St. Denis’s career in New York. So too did a number of prominent society matrons (including a sister and a daughter of J. Pierpont Morgan), who at one early juncture even rented a theater for her; as she recalled in her memoirs the “names of the patronesses meant attention in the newspapers. I was interviewed tirelessly.” The Duchess of Manchester was an important early advisor and patron to St. Denis in London, as was the extraordinarily wealthy Duchess of Thurn und Taxis in Vienna. The poet, critic, and wealthy aristocrat Hugo von Hofmannsthal figured prominently in St. Denis’s early European success, as did Harry Graf (count) Kessler, a patrician art critic, museum director, and son of a banker from Hamburg. In Berlin she started her performances with a special appearance for the press and “everyone of importance in Berlin ... and the papers the next morning established my success.” She adopted the same strategy in London, where a “committee” of prominent friends and fans arranged a special performance for the artistic and social elite, including princes, dukes, duchesses, and a maharajah as well as painters, sculptors, and playwrights. The “evening had the desired effect. The audience increased ... everyone but the King and Queen came ... and picture postcards of my dances began to appear on the streets.”Footnote 99

None of this was untypical. Early on in her dance career Maud Allan was supported by a circle of prominent American expatriates living in Brussels, including the American ambassador and his wife. Later, she gave a private performance for the King of England and Emperor of Germany at the elite spa Marienbad in 1907, met the Queen after performing at a party given by the Earl and Countess of Dudley, and formed a close social and personal connection with Margot Asquith, wife of the Prime Minister of England.Footnote 100 She earned the very substantial sum of £200 per night performing at private parties of the social and financial elite. Less happily, she reported that her patrons in Brussels had to protect her from the amorous advances of the King of Belgium, and that she had to speak sharply to the son of the Emperor of Germany before he would leave her alone during a journey by ship to India; but she recorded with evident pride her command performances for kings and emperors, counts and rajahs.Footnote 101 Margarethe Zelle/Mata Hari performed in a number of Paris salons, including those of the American heiress Natalie Clifford Barney and the extremely wealthy doctor, entrepreneur, and patron of the arts and sciences Henri de Rothschild; she went on to be the mistress of a series of wealthy men – bankers, aristocrats, and military officers.Footnote 102 Regina Woody/Nila Devi performed for wealthy patrons in both London and Paris, as well as in variety theater.Footnote 103 Allan and St. Denis gave private performances for royalty in Britain and Germany, as did Friderica Derra de Moroda in Russia, and both Mata Hari and Cléo de Mérode in Berlin; Tórtola Valencia may have had a relationship with Duke Franz Josef of Bavaria; Isadora Duncan danced for the Prince of Wales (shortly to become King of England); long sections of Loïe Fuller’s autobiography might have been titled “European Royalty I Have Known.”Footnote 104

In some cases, relationships like these ended in marriages into the European aristocracy. Olga Sellin/Desmond was briefly married to a Hungarian aristocrat; Rita Sacchetto married a Polish count; Liane de Pougy married a Rumanian prince.Footnote 105 But the tone of such relationships and of the milieu in which they thrived is perhaps better revealed by a letter home to his parents penned by Harry Graf Kessler in 1900, reporting that a friend “has a very cute and funny lover, an Australian who dances here in the Folies-Bergères. She’s named Miss Saharet and has the most charming way of dancing on a dinner table or on a piano.”Footnote 106 Saharet’s lover was Alfred Heymel, a wealthy wastrel and minor poet who was a fixture in Munich’s bohemian arts community.Footnote 107 Mata Hari was partially financially dependent on a series of wealthy (and mostly married) lovers. And a number of dancers on the margins of the early stages of the modern dance revolution had made their way partly or primarily as courtesans – Liane de Pougy, Cleo de Merode, or “La Belle Otero” (Caroline Otero).Footnote 108

The appeal of modern dance was, however, by no means limited to men; modern dancers’ connections with women of the upper class appear to have been at least as important. Wealthy women, not men, more often hired the modern dancers to perform at parties. “Society” women played a crucial role in launching modern dance by hiring Duncan and St. Denis to perform at parties in New York or at their summer homes in Rhode Island. Prominent American expatriate women played a crucial role as early patrons of the American dancers who launched the modern dance revolution in Europe. They included Winaretta Singer; another American heiress in Paris, Natalie Barney; in Britain the Duchess of Manchester, who was of Cuban parentage but raised in New Orleans; Madame Rienzini, an early patron of Regina Woody (and married to an Italian banker in London); and Maud Allan’s patron in Brussels, the American ambassador’s wife Natalie Townsend.Footnote 109

In part, this relationship can be explained by the role of aristocratic women as patrons of salons – more or less regular but informal social gatherings for influential figures from the arts, literature, politics, and sometimes finance. The thematic content of modern dance “worked” in this setting as well: “Oriental” themes appealed to the craze for Buddhism, New Thought, Theosophy, and “Eastern” décor in this social milieu around the turn of the twentieth century, while “Greek” models were familiar to them as well as part of European high culture.Footnote 110 Modern dance was, then, an appropriate adornment for private parties – like a string quartet, or a poetry reading.

In some cases these relationships with elite women may have been sexual. Here too, the thematics worked; for in addition to being the cradle of Western Civilization, ancient Greece was also widely understood to be the original home of homosexuality – including “Sapphic” love, particularly after the rediscovery of much of Sappho’s poetry in the early 1890s.Footnote 111 In fact it appears that the modern dance revolution played a not insignificant role in the establishment of the modern subculture of lesbianism. Loïe Fuller was more or less openly homosexual, and surrounded herself with adoring young female dancers – a role Duncan claimed, in her autobiography, to have found off-putting and incomprehensible.Footnote 112 But Duncan may have played deliberately on her sensual appeal to women, including the Princess de Polignac and Natalie Barney. In later years she appears at least to have penned rather explicit amorous poetry to women friends (“My kisses like a swarm of bees/Would find their way/Between thy knees”).Footnote 113 It may not be coincidental, too, that one of the more influential series of early photographs of Duncan was produced by the photo-atelier Elvira, which was operated by a radical feminist couple, Anita Augspurg and Sophia Goudstikker.Footnote 114 Tórtola Valencia appears to have had long-term relationships with at least two adopted “daughters.” The name of one was sometimes given as Rosita Corma, and sometimes as Rosa Carne Centellas – which might be roughly translated as Sparkly Pink Meat. Valencia was buried with her. Some newspapers made carefully veiled references to her preferences – for example referring to her as a “much-discussed Sappho” or hinting at a lover’s quarrel between Valencia and her English companion “Miss Nella” in a railway-car sleeping compartment.Footnote 115 Maud Allan was eventually – during World War I – at the center of a libel trial involving allegations of her homosexual relationship with Margot Asquith, or perhaps a romantic triangle involving both her and her husband; and she does appear to have had intimate relationships with other women later.Footnote 116

Whether with men or with women, over time such relationships were of declining importance, as modern dance established itself as a widely accepted performance genre with a reliable commercial market. Performances at private parties of the social elite continued to be an important source of revenue; but by 1910 the market was sufficiently robust that this was one of many income streams, and probably important primarily because it helped to keep the dancers in the media. This too was a marketing strategy – a whiff of polymorphic sexual adventurism, the cachet of “advanced” and/or decadent ideas and aristocratic admirers, a note of newsworthy scandal. A decade before marrying her Rumanian prince in 1910, for example, Liane de Pougy published in novel form a thinly veiled blow-by-blow account of her torrid affair with Natalie Barney.Footnote 117 This was a way of gaining media attention and marketing pull – one of those forms of “eccentricity” that prominent women cultivated to sustain media interest.Footnote 118

1.5 Modernity, America, Business

Collectively, then, the early modern dance stars adopted an extraordinarily effective multichannel marketing strategy, exquisitely suited to the emerging mass cultural market – for art, for entertainment, for fashion, for soft-core pornography, and ultimately also for a “modern” image of female selfhood. None of this was entirely new. Nineteenth-century ballet dancers too were required to be slender, ethereal creatures; as Deborah Jowitt pointed out, they too were “supple” and snakelike; they too embodied both “female sensuality and female chastity.” And a sizable proportion of the ballet repertoire, too, had been built around “Oriental” themes.Footnote 119 Nor was the cult of the female dancer as celebrity a novelty: The modern dancers of the turn of the century were clearly running down paths first laid down the great ballerinas of the romantic ballet, such as Carlotta Grisi, Marie Taglioni, or Fanny Elssler, who were also sometimes received with wild enthusiasm, as early as the 1830s and 1840s.Footnote 120 Even the classical references were not entirely new: the poet and critic Théophile Gautier, for example, had described Taglioni as having the same “rounded and polished forms” as a “divine marble [statue] from the times of Pericles,” and Fanny Elssler as resembling “figures from Herculaneum or Pompei” – already half a century before Isadora Duncan appeared.Footnote 121