Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Texts and Contexts: the Legend of St Edmund

- Part II Relics, Shrines and Pilgrimage: Encountering St Edmund at Bury

- Part III Beyond Bury: Dissemination and Appropriation

- Conclusion: ‘Martir, Mayde and Kynge’, and More

- Appendix 1 Synoptic Account of the Legend of St Edmund

- Appendix 2 Chronology of Significant Events and Texts Associated with the Cult of St Edmund

- Bibliography

- Index

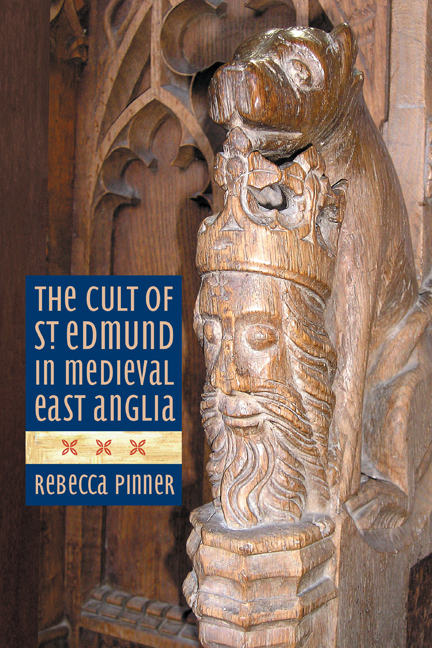

Chapter 10 - Images of St Edmund

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 May 2021

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Texts and Contexts: the Legend of St Edmund

- Part II Relics, Shrines and Pilgrimage: Encountering St Edmund at Bury

- Part III Beyond Bury: Dissemination and Appropriation

- Conclusion: ‘Martir, Mayde and Kynge’, and More

- Appendix 1 Synoptic Account of the Legend of St Edmund

- Appendix 2 Chronology of Significant Events and Texts Associated with the Cult of St Edmund

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

TRANSACTIONS between Bury and the cult in outlying areas are especially visible in the dozens of images of Edmund which adorned East Anglian churches. Visual culture was fundamental to the dissemination of saintly identities at the parochial level as well as at the cult centre. Richard Gameson maintains that some communities ‘immortalis[ed] their particular holy man or woman in paint, stone, wood and precious metals as much as, if not more so, than in verse and prayer’. Hagiographic art could fulfil many functions and its didactic potential was recognised by contemporaries. The familiar, homogenised code of church art provided a highly visible, pervasive reminder of the events described in sermons and commemorated in services. Contemporary authors frequently invoked Gregory I in support of art as a means of instructing the illiterate. In Dives and Pauper, for example, an early fifteenth-century prose commentary on the Ten Commandments, Dives, a layman, asks his adviser, Pauper, to teach him about images, the ‘book of lewyd peple’. However, the notion of medieval church art as simply picture books for the illiterate fails to acknowledge the complex range of potential responses. Gameson, for instance, suggests that ‘by the means of depictions, one could appropriate and possess any saint or particular figure’. ‘Appropriation’ implies a degree of ownership which the elevated status of saints within medieval religion renders surprising; saints were, after all, the conduits through which flowed the power of God. Rather than a one-way transaction, with the saint obediently at the behest of the community, the decision to depict a particular saint represented the creation of a mutually beneficent relationship, the ‘debt of interchanging neighbourhood’ referred to by Caxton in his translation of the Golden Legend. An individual or parochial community would have hoped to attract the intercessory favour of the one depicted in return for identifying that particular saint as especially worthy of devotion. It was above all the reputation of the holy man or woman to act effectively on their behalf, whether based upon evidence from their life or, frequently, their posthumous activities, which encouraged those who sought their favour and intercession.

Images played a key role in this process, able to represent the identity of a saint as understood by those involved in the creation of the image, whether at the level of commissioning, design or production.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cult of St Edmund in Medieval East Anglia , pp. 193 - 226Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015