Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Back to the Future? Idioms of ‘displaced time’ in South African composition

- Chapter 2 Apartheid's Musical Signs: Reflections on black choralism, modernity and race-ethnicity in the segregation era

- Chapter 3 Discomposing Apartheid's Story: Who owns Handel?

- Chapter 4 Kwela's White Audiences: The politics of pleasure and identification in the early apartheid period

- Chapter 5 Popular Music and Negotiating Whiteness in Apartheid South Africa

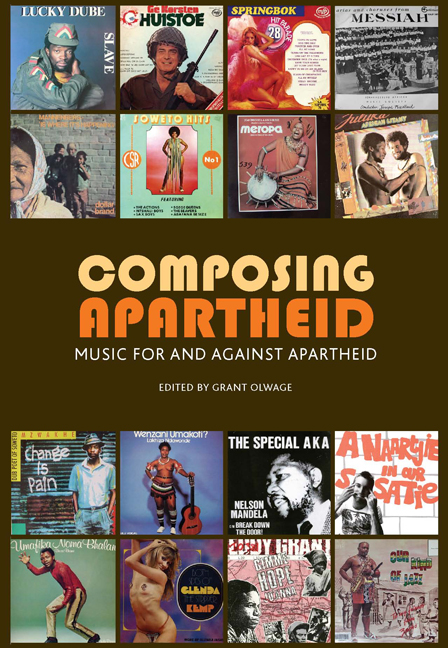

- Chapter 6 Packaging Desires: Album covers and the presentation of apartheid

- Chapter 7 Musical Echoes: Composing a past in/for South African jazz

- Chapter 8 Singing Against Apartheid: ANC cultural groups and the international anti-apartheid struggle

- Chapter 9 ‘Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika’: Stories of an African anthem

- Chapter 10 Whose ‘White Man Sleeps’ Aesthetics? and politics in the early work of Kevin Volans

- Chapter 11 State of Contention: Recomposing apartheid at Pretoria's State Theatre, 1990–1994. A personal recollection

- Chapter 12 Decomposing Apartheid: Things come together

- Chapter 13 Arnold van Wyk's Hands

- Contributors

- Index

Chapter 7 - Musical Echoes: Composing a past in/for South African jazz

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Back to the Future? Idioms of ‘displaced time’ in South African composition

- Chapter 2 Apartheid's Musical Signs: Reflections on black choralism, modernity and race-ethnicity in the segregation era

- Chapter 3 Discomposing Apartheid's Story: Who owns Handel?

- Chapter 4 Kwela's White Audiences: The politics of pleasure and identification in the early apartheid period

- Chapter 5 Popular Music and Negotiating Whiteness in Apartheid South Africa

- Chapter 6 Packaging Desires: Album covers and the presentation of apartheid

- Chapter 7 Musical Echoes: Composing a past in/for South African jazz

- Chapter 8 Singing Against Apartheid: ANC cultural groups and the international anti-apartheid struggle

- Chapter 9 ‘Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika’: Stories of an African anthem

- Chapter 10 Whose ‘White Man Sleeps’ Aesthetics? and politics in the early work of Kevin Volans

- Chapter 11 State of Contention: Recomposing apartheid at Pretoria's State Theatre, 1990–1994. A personal recollection

- Chapter 12 Decomposing Apartheid: Things come together

- Chapter 13 Arnold van Wyk's Hands

- Contributors

- Index

Summary

And I∇m glad to say that I∇m home

I∇m home to stay.

Africa, Africa.

I∇ve come home; I∇ve come home.

To feel my people's warmth,

To shelter ‘neath your trees,

To catch the summer breeze;

Africa, Africa.

I∇ve come home, I∇ve come home.

I∇m home to smell your earth,

To laugh with your children,

To feel your sun shining down on me;

Africa, Africa.

I∇ve come home, I∇ve come home.

(‘Africa’ by Sathima Bea Benjamin)

I have extraordinarily vivid memories of hearing South African musicians Sathima Bea Benjamin and Abdullah Ibrahim in two specific live performances in the United States. The first occasion was the JVC Jazz Festival in New York City in c. 1990. Abdullah performed a solo piano concert in the Weill Recital Room at Carnegie Hall. The second was a performance by Sathima at the Kennedy Center's Women in Jazz series held in Washington DC more than a decade later. Neither occasion was the first or only time I heard the couple perform. Nevertheless, these two events stand out in my memory for the profound way in which the sounds emanating from the grand piano, and those carried by the human voice, evoked a full-bodied, multi-sensory response in me. In the first moment, it seemed as if I could see, smell, feel, and hear the Bo-Kaap district of central Cape Town. The second moment elicited a deep sense of longing, an aching in my body for the space called ‘Africa’ that Sathima sang about. These utterances were musical echoes in diaspora, and probably I had been away from South Africa far too long.

Though I was born in Cape Town, and spent my childhood in South Africa, what I heard in those moments were not the actual memories of sounds and places I had experienced earlier in my life. Rather, these were poetic invocations expressed out of a longing to return home that I felt in the music of the two South Africans. In each performance the voice and instrumental sounds made contact with me as an audience member, acoustically generating images of faraway places for a fellow South African in America.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Composing ApartheidMusic for and against apartheid, pp. 137 - 154Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2008