Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Commemorating Race and Empire in the First World War Centenary

- Rediscovering and Rehabilitating Empire, 2014-2018

- From ‘Coolie’ to Transnational Agent: the ‘Afterlives’ of World War One Chinese Workers

- Marigolds and Poppies: Commemorating ‘Indian’ War Dead

- Situating the Belgian Congo in Belgium's First World War Centenary

- Maori and Great War Commemoration in New Zealand: Biculturalism and the Politics of Forging National Memory

- Representing Race and Empire, 1900-1920

- Memorialising Race and Empire in Settler Societies, 1919-2018

- Contibutor Biographies

- Index terms

Marigolds and Poppies: Commemorating ‘Indian’ War Dead

from Rediscovering and Rehabilitating Empire, 2014-2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Commemorating Race and Empire in the First World War Centenary

- Rediscovering and Rehabilitating Empire, 2014-2018

- From ‘Coolie’ to Transnational Agent: the ‘Afterlives’ of World War One Chinese Workers

- Marigolds and Poppies: Commemorating ‘Indian’ War Dead

- Situating the Belgian Congo in Belgium's First World War Centenary

- Maori and Great War Commemoration in New Zealand: Biculturalism and the Politics of Forging National Memory

- Representing Race and Empire, 1900-1920

- Memorialising Race and Empire in Settler Societies, 1919-2018

- Contibutor Biographies

- Index terms

Summary

India is a nation in which paradoxically, the past is omnipresent but the age of any given structure can be annoyingly indeterminate. It is a place where the past can be both absolutely present and frustratingly remote; in which versions of the past co-exist; in which they can contend without necessary contradiction, though sometimes bringing risk of denunciation, controversy and even death. It is a culture in which layers of meaning and significance accrete around historical events – even historical events recorded in the daily newspaper. India takes its many pasts seriously – but can ignore aspects of its history in ways unthinkable in other societies. The Great War of 1914-1918 is an inescapable part of the history of Australia or New Zealand, and even in Britain remains a part of the currency of everyday speech and popular culture. In the nations of South Asia, by contrast, the Great War remains obscure and unimportant.

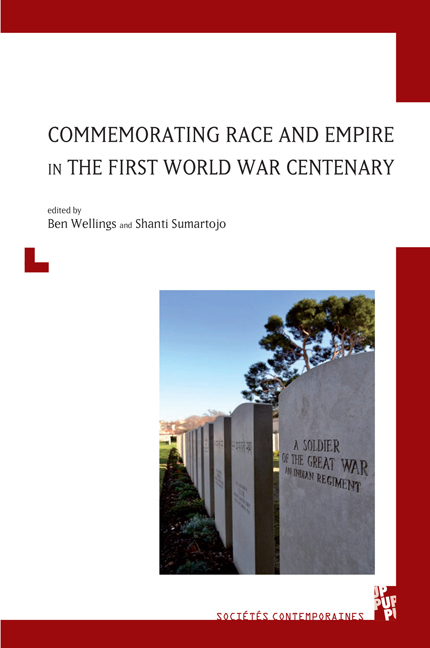

Given the scale of undivided India's involvement in the Great War this neglect offers a further paradox. In the course of the First World War (and several associated minor conflicts, such as ‘frontier’ expeditions and the third Anglo Afghan war of 1919) about a million men from British India and its ‘princely states’ served and some 74,000 died, about 62,000 in operations overseas. India played an important part in the British empire's war effort, not least as a reservoir of trained manpower, becoming the mainstay of campaigns in the Middle East. That endeavour was commemorated in the war's aftermath, and British India commemorated its war dead much like other parts of the empire, as it did during a Second World War. In 1947, however, British India became the independent nations of India and Pakistan (which in turn spawned Bangla Desh in 1971), while Burma became independent in 1948. Sri Lanka's memory of the Great War was almost entirely ‘white’, through the service of the Ceylon Planters Rifles and European volunteers. They were commemorated by memorials, some of which were appropriated by a nation traumatised by a more recent civil conflict. From independence commemoration of the First World War turned to apathy: these conflicts were seen as not being India's wars; those who died had served the British Raj.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2018