Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Commemorating Race and Empire in the First World War Centenary

- Rediscovering and Rehabilitating Empire, 2014-2018

- From ‘Coolie’ to Transnational Agent: the ‘Afterlives’ of World War One Chinese Workers

- Marigolds and Poppies: Commemorating ‘Indian’ War Dead

- Situating the Belgian Congo in Belgium's First World War Centenary

- Maori and Great War Commemoration in New Zealand: Biculturalism and the Politics of Forging National Memory

- Representing Race and Empire, 1900-1920

- Memorialising Race and Empire in Settler Societies, 1919-2018

- Contibutor Biographies

- Index terms

Maori and Great War Commemoration in New Zealand: Biculturalism and the Politics of Forging National Memory

from Rediscovering and Rehabilitating Empire, 2014-2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Commemorating Race and Empire in the First World War Centenary

- Rediscovering and Rehabilitating Empire, 2014-2018

- From ‘Coolie’ to Transnational Agent: the ‘Afterlives’ of World War One Chinese Workers

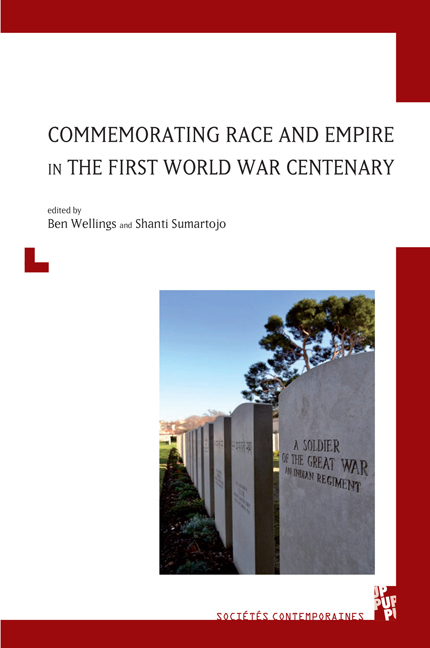

- Marigolds and Poppies: Commemorating ‘Indian’ War Dead

- Situating the Belgian Congo in Belgium's First World War Centenary

- Maori and Great War Commemoration in New Zealand: Biculturalism and the Politics of Forging National Memory

- Representing Race and Empire, 1900-1920

- Memorialising Race and Empire in Settler Societies, 1919-2018

- Contibutor Biographies

- Index terms

Summary

When Lord Liverpool, the Governor of New Zealand announced from the steps of Parliament in Wellington on August 5, 1914 Britain's declaration of war against Germany, there was no sign of doubt among the large crowd gathered that the former colony would enthusiastically support the campaign. Prime Minister William Massey had a few days before offered London a New Zealand Expeditionary Force, and announced to Parliament that he had ‘no fear of volunteers not being forthcoming.’ New Zealand was the smallest and most recent of the British settler societies, with formal Dominion status granted only seven years before, and the overwhelming majority of its population in 1914 of just over a million people were of British origin, and regarded themselves as British subjects. The term ‘New Zealander’ had been used through the nineteenth century, the period of the colony's European settlement, but referred specifically to the indigenous Maori, and a sense of distinct national identity for the dominant Pakeha or white European population was only beginning to emerge in the early twentieth century. While Massey was only initially correct in his confidence in volunteers – conscription was applied in 1916 – ultimately, around 100,000 New Zealanders served in the War in the New Zealand forces, over 16,000 of whom died. 2,200 of those who served were Maori, almost half of whom lost their lives.

In New Zealand as in the other Dominions, popular experiences of the First World War, both at home and overseas have become retrospectively suffused with cultural and ideological meaning, and closely intertwined with the construction, articulation and deployment of national identity. In New Zealand, this has particularly been the case in the twenty-first century, and there has been extensive state support for commemoration of the War's centenary, both from the conservative National Party government, and in the planning stages under the previous Labour government. This is part of course of a broader project to remember the War in Britain, France, Belgium and Australia, which itself intersects with expanding academic interest in the broader politics of histo–rical memory. This political and scholarly nexus has been especially salient in Australia and New Zealand, where the Great War has been taken as a key transi–tional event in the emergence of a new and distinct nationhood.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2018