Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Commemorating Race and Empire in the First World War Centenary

- Rediscovering and Rehabilitating Empire, 2014-2018

- From ‘Coolie’ to Transnational Agent: the ‘Afterlives’ of World War One Chinese Workers

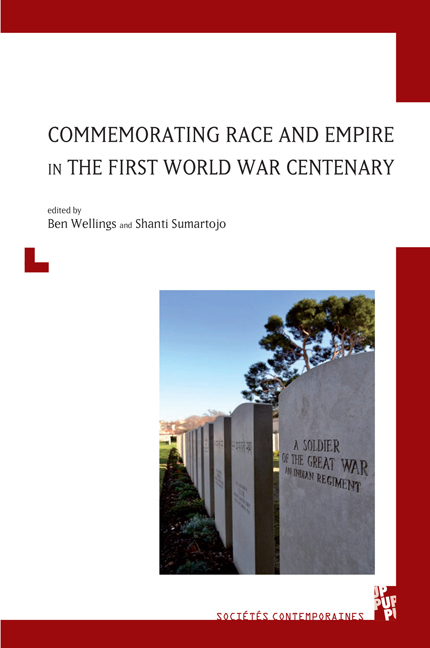

- Marigolds and Poppies: Commemorating ‘Indian’ War Dead

- Situating the Belgian Congo in Belgium's First World War Centenary

- Maori and Great War Commemoration in New Zealand: Biculturalism and the Politics of Forging National Memory

- Representing Race and Empire, 1900-1920

- Memorialising Race and Empire in Settler Societies, 1919-2018

- Contibutor Biographies

- Index terms

From ‘Coolie’ to Transnational Agent: the ‘Afterlives’ of World War One Chinese Workers

from Rediscovering and Rehabilitating Empire, 2014-2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Commemorating Race and Empire in the First World War Centenary

- Rediscovering and Rehabilitating Empire, 2014-2018

- From ‘Coolie’ to Transnational Agent: the ‘Afterlives’ of World War One Chinese Workers

- Marigolds and Poppies: Commemorating ‘Indian’ War Dead

- Situating the Belgian Congo in Belgium's First World War Centenary

- Maori and Great War Commemoration in New Zealand: Biculturalism and the Politics of Forging National Memory

- Representing Race and Empire, 1900-1920

- Memorialising Race and Empire in Settler Societies, 1919-2018

- Contibutor Biographies

- Index terms

Summary

Introduction

In April 2010 China Central Television's international English-language channel (Channel Nine) broadcast a six-episode documentary in its series ‘New Frontiers’ hosted by Ji Xiaojun on the 130,000-plus Chinese workers recruited by the French and British governments during World War One. In portentous tones Ji Xiaojun boldly announced in the first episode that the World War One Chinese workers ‘stood shoulder to shoulder’ with British and French troops to combat German military aggression, and that in the process 20,000 of them were killed. Such a valuable contribution to the Allied victory, Ji continued, was not fully acknowledged by France and Britain until fifty years after the end of the war. Overall, the programme depicted the episode as a shining example of China's positive and beneficial interaction with the world predating the current era of China's ‘globalisation’ (in Chinese referred to as duiwai kaifang or ‘opening up to the outside world’) that is declared to have begun with the post-Mao market reforms launched in 1978-1980. In fact, the China Central Television (CCTV) programme signalled an extraordinary revival of interest in the story of World War One Chinese workers, which – notwithstanding the programme's reference to the tardy recognition of the Chinese workers’ contribution by Britain and France – had long been marginalised or completely ignored in China itself, a fact conveniently overlooked by the CCTV documentary.

After briefly detailing the wartime role of the Chinese workers and the ways in which it was described by Chinese officials and intellectuals at the time, this chapter will explore the reasons why the entire episode of the allied recruitment of Chinese labour was completely ignored after 1949 in China, and why there has been such a resurgence of interest in the World War One Chinese workers in contemporary China. It is worth noting, however, that such a phenomenon paral–lels a similar ‘rediscovery’ in France today of the World War One Chinese workers. The predominantly Eurocentric approach to World War One that characterized much of French (and western) scholarship until relatively recently meant that in France it was not until 2010 that the first major international conference on the role and experiences of Chinese workers in wartime France was held, jointly organised by the University of the Littoral in Boulogne and In Flanders Field Museum in Ypres, Belgium and resulting in a major French-language publication two years later.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2018