Book contents

- Frontmmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One Introduction

- Chapter Two The City in Context: An Historical Ambivalence

- Chapter Three City of Light: Paris as Spectacle

- Chapter Four City of Darkness: The Camera Goes Down the Streets: ‘The Hidden Spirit Under the Familiar Façade’

- Chapter Five Divided City: The Divided City in Context

- Chapter Six Conclusion

- Notes

- Appendices

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index

- Film Culture in Transition General Editor: Thomas Elsaesser

Chapter Five - Divided City: The Divided City in Context

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 25 January 2021

- Frontmmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One Introduction

- Chapter Two The City in Context: An Historical Ambivalence

- Chapter Three City of Light: Paris as Spectacle

- Chapter Four City of Darkness: The Camera Goes Down the Streets: ‘The Hidden Spirit Under the Familiar Façade’

- Chapter Five Divided City: The Divided City in Context

- Chapter Six Conclusion

- Notes

- Appendices

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index

- Film Culture in Transition General Editor: Thomas Elsaesser

Summary

The critic Georges Champeaux noted that PIÈGES (1939), Robert Siodmak's final film made in France before departing for the United States, seemed to be like a dark Parisian police drama but indeed it was something else. “PIÈGES has neither the cut nor the rhythm of a police film,” he stated. “What it seems like is a succession of sketches destined to bring its comical or bizarre characters to life in front of us. The slowness and, it has to be said, the talent with which the director Robert Siodmak describes the social milieu of each of his characters scarcely contributes to strengthening the film's illusion”. Fritz Lang's only film made in France, LILIOM, was given similarly contradictory reviews at the time, no doubt in part because halfway through the film, the eponymous lead, a Parisian mauvais garçon played by Charles Boyer, leaves the Parisian zone for a fantastic journey to heaven. Many of LILIOM's critics also pointed out the national hybridity of the film, which was based on a play by the Hungarian playwright Frederic Molnar, produced by the renowned U.F.A. producer Erich Pommer, and directed by Germany's most famous director, Fritz Lang. To the right-wing cultural press, for example, LILIOM was a prime example of the dangers of having a multi-cultural film culture in France. The virulently anti-Semitic François Vinneuil saw “this French-Jewish-Hungarian collaboration” as a return to “that bizarre and boring cinematic country produced by U.F.A.'s French-German dramas [which was] a ‘no man's land’, a Babel emptied of all character lying a lot closer to the Sprée than to the Seine”.

PIÈGES and LILIOM are further examples of how different groups of émigrés portrayed the French capital. In part, they consolidate the ideas discussed in the preceding chapters. Yet at the same time, they also express a more fragmented notion of the conventions of Parisian representation, and in this sense, they are both divided on a textual and representational level. To understand this sense of division we should examine the films in relation to three overlapping contexts. Firstly, we need to consider the way the two productions actually frame the period in question.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

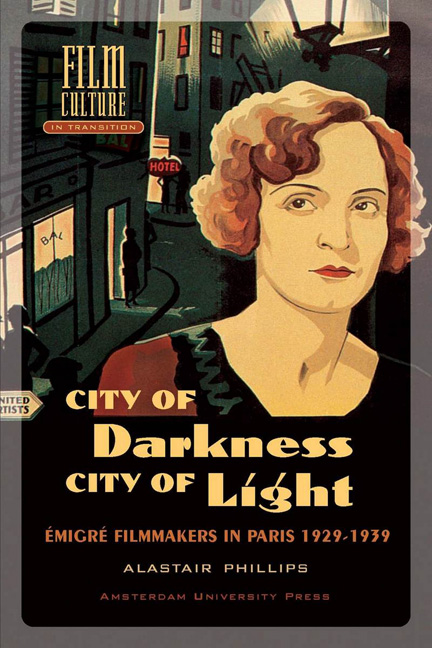

- City of Darkness, City of LightÉmigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929–1939, pp. 149 - 170Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2003