Cinemas of the Mozambican Revolution

Cinemas of the Mozambican Revolution Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 July 2020

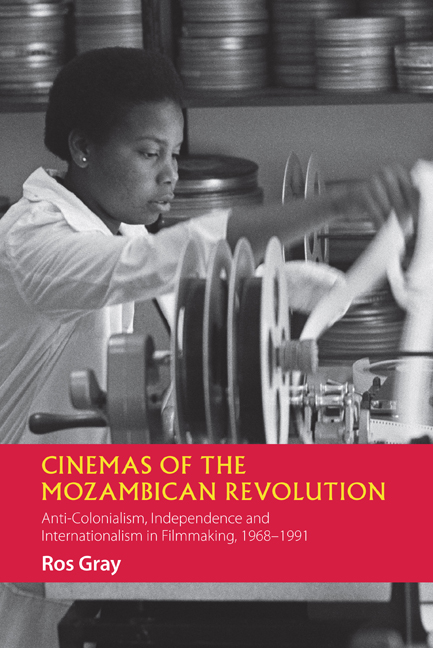

By 1977, the INC was functioning as an institute in command of acquisition and distribution, the profits from which were channelled into the production of films made by a team that included young people who would have been cut off from the possibility of becoming filmmakers under colonialism. The equipment purchased by Ron and Ophera Hallis had made it possible to shoot films on the cheaper format of 16mm that could then be transferred to 35mm for projection in the cinemas. Taking cinema to ‘the people’ and collectivising production involved not only building up the INC's institutional capacity but also dismantling the hierarchies that had structured the colonial film production. Chapter 3 examined how a number of filmmakers explored the emancipatory potential of capturing scenes of everyday life on film. However, such projects played a minor part in comparison with the bulk of the INC's productions, which sought to harness cinema to the work of political education and the dissemination of information.

This chapter addresses the didactic purpose of many of the INC's film productions, the role that cinema was understood to play in the ‘battle of information’, and the ways in which films made during these years address their audiences as learners. The battle of information referred in part to the effort to keep Mozambicans informed about the radical changes taking place across the country, explaining the reasons for the challenges they faced and the ways Frelimo intended to address problems of supplies and logistical difficulties in the face of natural disasters and the ruination of infrastructure caused by the colonial war and acts of sabotage by departing Portuguese. In 1977, Frelimo announced that it was transforming into a vanguard Marxist–Leninist party, aligning itself more closely with the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. The dissemination of information to Mozambicans thus also involved instruction on how to participate in the revolution that was unfolding in the correct way. This chapter analyses how short documentaries and the first version of the Kuxa Kanema newsreel that was produced in 1978 and 1979 answered to this demand, exploring the extent to which forms of cinema pedagogy may be understood as anticipatory rather than necessarily authoritarian. The battle of information also involved the crucial work that film could perform in challenging the narratives about the region that were circulated by the white minority regimes in Rhodesia and South Africa.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure no-reply@cambridge.org is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle.

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive.