Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Cartography

- 1 Materialities, subjectivities and spatial transformation in Johannesburg

- Section A The macro trends

- Section B Area-based transformations

- Section C Spatial identities

- 23 Footprints of Islam in Johannesburg

- 24 Being an immigrant and facing uncertainty in Johannesburg: The case of Somalis

- 25 On ‘spaces of hope’: Exploring Hillbrow's discursive credoscapes

- 26 The Central Methodist Church

- 27 The Ethiopian Quarter

- 28 Urban collage: Yeoville

- 29 Phantoms of the past, spectres of the present: Chinese space in Johannesburg

- 30 The notice

- 31 Inner-city street traders: Legality and spatial practice

- 32 Waste pickers/informal recyclers

- 33 The fear of others: Responses to crime and urban transformation in Johannesburg

- 34 Black urban, black research: Why understanding space and identity in South Africa still matters

- Contributors

- Photographic credits

- Acronyms

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Index

25 - On ‘spaces of hope’: Exploring Hillbrow's discursive credoscapes

from Section C - Spatial identities

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- Cartography

- 1 Materialities, subjectivities and spatial transformation in Johannesburg

- Section A The macro trends

- Section B Area-based transformations

- Section C Spatial identities

- 23 Footprints of Islam in Johannesburg

- 24 Being an immigrant and facing uncertainty in Johannesburg: The case of Somalis

- 25 On ‘spaces of hope’: Exploring Hillbrow's discursive credoscapes

- 26 The Central Methodist Church

- 27 The Ethiopian Quarter

- 28 Urban collage: Yeoville

- 29 Phantoms of the past, spectres of the present: Chinese space in Johannesburg

- 30 The notice

- 31 Inner-city street traders: Legality and spatial practice

- 32 Waste pickers/informal recyclers

- 33 The fear of others: Responses to crime and urban transformation in Johannesburg

- 34 Black urban, black research: Why understanding space and identity in South Africa still matters

- Contributors

- Photographic credits

- Acronyms

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Index

Summary

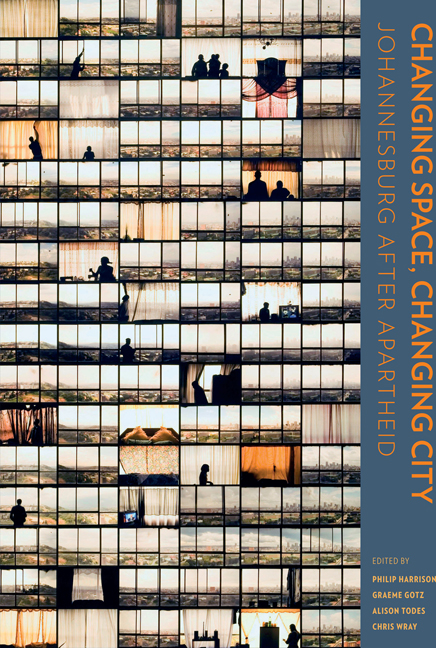

As legend has it, Hillbrow is one of the deepest circles of Dante's hell, a chaotic swirl of drug dealers and murderers that any visitor would be lucky to escape. A post-apocalyptic Wild West that leaves hardened police pale with fear. People might even compare it to a war zone. But it is NOT a war zone. Alongside this, there is a vibrancy and a sense of community that is certainly not found in any of Johannesburg's walled-off northern suburbs and sterile malls.

– Nessman 2002: 194Despite its reputation, severe physical degradation, relatively high rates of unemployment, and a history of being ‘redlined’ by financial institutions, Hillbrow remains a ‘popular’ urban realm. Here, the resident population has doubled in the past 20 years, as a significant number of newcomers to the city tend to first locate themselves in this inner-city neighbourhood. Hillbrow therefore functions as a ‘port of entry’ to Johannesburg for many who desire to engage in the perceived economic opportunities of the city. It is home to a diverse resident constituency, and at least 38 per cent of its current population is foreign-born. The tendency for migrants, immigrants or transnationals to ‘cluster’ in a neighbourhood due to established networks, shared language or cultural practices is not unique to Johannesburg. Yet, Hillbrow – oft en dubbed by locals as ‘little Lagos’ – has become a zone of great vulnerability, attracting hostility, xenophobia and violence. Accordingly, Hillbrow is a domain to which few want to belong, or in which few are able to establish their roots. Still, it keeps alive residents’ hopes for stability and security somewhere else. Hillbrow thus has much in common with other African urban contexts that are becoming accustomed to ever-increasing uncertainty, cross-border mobility and informalisation, which, in turn, contribute to the disconnect felt by many urban dwellers (Appiah 2006; Edjabe and Pieterse 2011).

However, as Nessman (2002) suggests, there is something else besides decay and chaos happening in Hillbrow. Here, there also exists ‘a vibrancy’ and some ‘sense of community’ that is founded, to a large extent, on local credoscapes, since faith identities facilitate ‘spaces of hope’ for at least 70 per cent of Hillbrow's residents (Winkler 2006).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Changing Space, Changing CityJohannesburg after apartheid, pp. 487 - 493Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2014