Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Preamble

- General Introduction

- Woodlands and Scrub

- Introduction to Woodlands and Scrub

- Key To Woodlands and Scrub

- Community Descriptions

- W1 Salix Cinerea-Galium Palustre woodland

- W2 Salix Cinerea-Betula Pubescens-Phragmites Australis Woodland

- W3 Salix Pentandra-Carex Rostrata Woodland

- W4 Betula Pubescens-Molinia Caerulea Woodland

- W5 Alnus Glutinosa-Carex Paniculata Woodland

- W6 Alnus Glutinosa-Urtica Jzozca Woodland

- W7 Ainus Glutinosa-Fraxinus Excelsior-Lysimachia Nemorum Woodland

- W8 Fraxinus Excelsior-Acer Campestre-Mercurialis Perennis Woodland

- W9 Fraxinus Excelsior-Sorbus Aucuparia-Mercurialis Perennis Woodland

- W10 Quereus Robur-Pteridium Aquilinum-Rubus Fruticosus Woodland

- W11 Quereus Petraea-Betula Pubescens-Oxalis Acetosella Woodland

- W12 Fagus Sylvatica-Mercurialis Perennis Woodland

- W13 Taxus Baccata Woodland

- W14 Fagus Sylvatica-Rubus Fruticosus Woodland

- W15 Fagus Sylvatica-Deschampsia Flexuosa Woodland

- W16 Quereus spp.-Betula spp.-Deschampsia Flexuosa Woodland

- W17 Quereus Petraea-Betula Pubescens-Dicranum Majus Woodland

- W18 Pinus Sylvestris-Hylocomium Splendens Woodland

- W19 Juniperus Communis Ssp. Communis-Oxalis Acetosella Woodland

- W20 Salix Lapponum-Luzula Sylvatica Scrub

- W21 Crataegus monogyna-Hedera helix scrub

- W22 Prunus Spinosa-Rubus Fruticosus Scrub

- W23 Ulex Europaeus-Rubus Fruticosus Scrub

- W24 Rubus Fruticosus-Holcus Lanatus Underscrub

- W25 Pteridium Aquilinum-Rubus Fruticosus Underscrub

- Index of Synonyms to Woodlands and Scrub

- Index of Species in Woodlands and Scrub

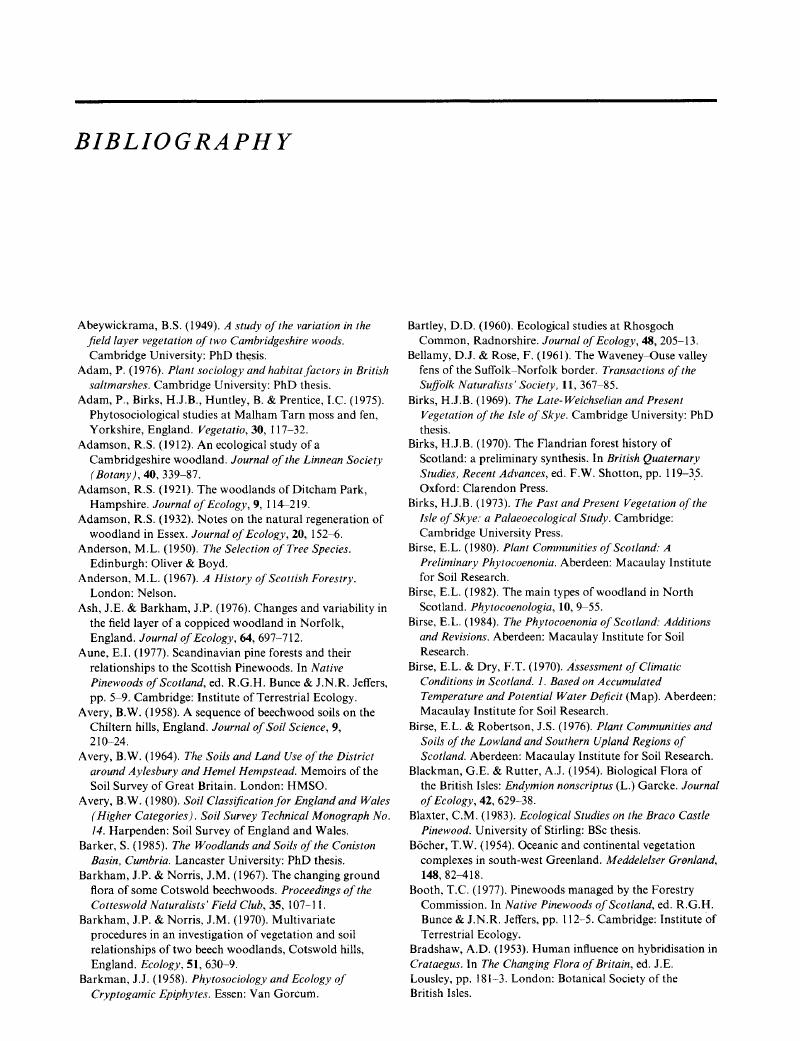

- Bibliography

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 July 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Preamble

- General Introduction

- Woodlands and Scrub

- Introduction to Woodlands and Scrub

- Key To Woodlands and Scrub

- Community Descriptions

- W1 Salix Cinerea-Galium Palustre woodland

- W2 Salix Cinerea-Betula Pubescens-Phragmites Australis Woodland

- W3 Salix Pentandra-Carex Rostrata Woodland

- W4 Betula Pubescens-Molinia Caerulea Woodland

- W5 Alnus Glutinosa-Carex Paniculata Woodland

- W6 Alnus Glutinosa-Urtica Jzozca Woodland

- W7 Ainus Glutinosa-Fraxinus Excelsior-Lysimachia Nemorum Woodland

- W8 Fraxinus Excelsior-Acer Campestre-Mercurialis Perennis Woodland

- W9 Fraxinus Excelsior-Sorbus Aucuparia-Mercurialis Perennis Woodland

- W10 Quereus Robur-Pteridium Aquilinum-Rubus Fruticosus Woodland

- W11 Quereus Petraea-Betula Pubescens-Oxalis Acetosella Woodland

- W12 Fagus Sylvatica-Mercurialis Perennis Woodland

- W13 Taxus Baccata Woodland

- W14 Fagus Sylvatica-Rubus Fruticosus Woodland

- W15 Fagus Sylvatica-Deschampsia Flexuosa Woodland

- W16 Quereus spp.-Betula spp.-Deschampsia Flexuosa Woodland

- W17 Quereus Petraea-Betula Pubescens-Dicranum Majus Woodland

- W18 Pinus Sylvestris-Hylocomium Splendens Woodland

- W19 Juniperus Communis Ssp. Communis-Oxalis Acetosella Woodland

- W20 Salix Lapponum-Luzula Sylvatica Scrub

- W21 Crataegus monogyna-Hedera helix scrub

- W22 Prunus Spinosa-Rubus Fruticosus Scrub

- W23 Ulex Europaeus-Rubus Fruticosus Scrub

- W24 Rubus Fruticosus-Holcus Lanatus Underscrub

- W25 Pteridium Aquilinum-Rubus Fruticosus Underscrub

- Index of Synonyms to Woodlands and Scrub

- Index of Species in Woodlands and Scrub

- Bibliography

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- British Plant Communities , pp. 385 - 395Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1991