Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Edith of Wilton and the Writing of Women's History

- 2 Audrey Abroad: Spiritual and Genealogical Filiation in the Middle English Lives of Etheldreda

- 3 Henry Bradshaw's Life of Werburge and the Limits of Holy Incorruption

- 4 The Limits of Narrative History in the Written and Pictorial Lives of Edward the Confessor

- 5 The Limits of Poetic History in Lydgate's Edmund and Fremund and the Harley 2278 Pictorial Cycle

- Bibliography

- Index

4 - The Limits of Narrative History in the Written and Pictorial Lives of Edward the Confessor

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2015

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Edith of Wilton and the Writing of Women's History

- 2 Audrey Abroad: Spiritual and Genealogical Filiation in the Middle English Lives of Etheldreda

- 3 Henry Bradshaw's Life of Werburge and the Limits of Holy Incorruption

- 4 The Limits of Narrative History in the Written and Pictorial Lives of Edward the Confessor

- 5 The Limits of Poetic History in Lydgate's Edmund and Fremund and the Harley 2278 Pictorial Cycle

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

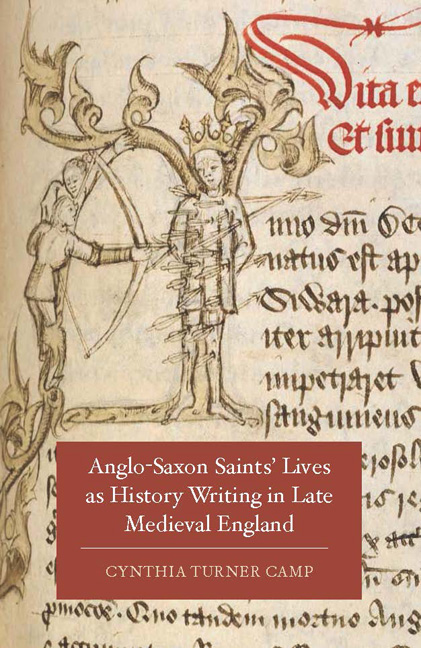

The Wilton Diptych preserves one of the most famous – and most typical – images of Edward the Confessor. On the left panel, a youthful-looking Richard II kneels before the Virgin Mary and her angels, who occupy the right panel. Richard is flanked by his three favorite saints: John the Baptist, Edward the Confessor, and Edmund of Bury. Edward stands robed in cream and ermine, crowned and white-bearded, prominently holding a ring. Similar images of Edward proliferated across late medieval England – in royal apartments, on rood-screens, throughout parish glazing programs, in the great cathedrals' statuary – making Edward easily recognizable in medieval art. Moreover, as the last representative of Wessex kingship, arguably the last legitimate ruler before the Conquest, and a canonized saint to boot, Edward (1003 × 1006–1066) offered all the features of a national saint along the lines of Louis IX of France or Olaf of Norway. Yet he became neither national saint nor definitive patron of English kingship, despite Plantagenet kings' promotion of Edward as a holy antecessor.

The erratic nature of Edward's cult is seen in the contrast between this widespread iconography and the paucity of his vernacular lives. Unlike the other saints I discuss, Edward inspired no lengthy, original Middle English life. Both Henry II and Henry III did earlier receive monastic-produced lives, a Latin vita from Aelred of Rievaulx (which would become the foundation for all subsequent lives) and a French vie from Matthew Paris, respectively; nevertheless, no Middle English life was produced for Richard II, despite Richard's active veneration and use of Edward's conjoined royal and saintly features. Nor did Westminster Abbey commission a life to enhance its prestige along the lines of Lydgate's Edmund and Fremund or Bradshaw's Werburge. After Paris's vie, Edward was celebrated in architecture, visual art, and ceremony, but was commemorated verbally only in two short, derivative lives integrated into Middle English legendaries, neither of which appears to have any connections to abbey or king.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015