Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Edith of Wilton and the Writing of Women's History

- 2 Audrey Abroad: Spiritual and Genealogical Filiation in the Middle English Lives of Etheldreda

- 3 Henry Bradshaw's Life of Werburge and the Limits of Holy Incorruption

- 4 The Limits of Narrative History in the Written and Pictorial Lives of Edward the Confessor

- 5 The Limits of Poetic History in Lydgate's Edmund and Fremund and the Harley 2278 Pictorial Cycle

- Bibliography

- Index

3 - Henry Bradshaw's Life of Werburge and the Limits of Holy Incorruption

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2015

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

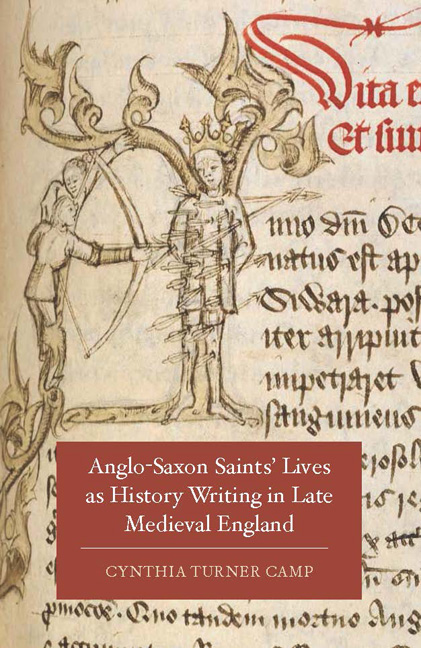

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Edith of Wilton and the Writing of Women's History

- 2 Audrey Abroad: Spiritual and Genealogical Filiation in the Middle English Lives of Etheldreda

- 3 Henry Bradshaw's Life of Werburge and the Limits of Holy Incorruption

- 4 The Limits of Narrative History in the Written and Pictorial Lives of Edward the Confessor

- 5 The Limits of Poetic History in Lydgate's Edmund and Fremund and the Harley 2278 Pictorial Cycle

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Mercia has always been a historical fantasy. The most powerful kingdom of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, it is represented differently from age to age, perpetually reconstructed geographically and temporally. Its origins are shrouded in Germanic myths, leaving to historians only ‘created remembrances … [that] have been honed and redefined in subsequent centuries as kingdoms themselves grew and reformed themselves’. Outside its core domain, the subkingdoms incorporated into the Mercian hegemony throughout the seventh and eighth centuries varied in their political, ethnic, and territorial makeup, such that ‘being Mercian seems to have been a more flexible commodity’ than being part of other Saxon kingdoms. That Mercian malleability lent it to re-imagination in every generation, from Felix of Crowland in the eighth century to Geoffrey Hill in the twentieth. It is fitting, therefore, that the monks of Chester – a city only falling within Mercia's most expansive orbit – would turn to this protean kingdom to invent for themselves an ancient, holy, and politically independent origin. Unlike Audrey's hagiographers, who use her holy kinship to claim roots in a broadly imagined Anglo-Saxon past, the Chester monk-poet Henry Bradshaw seeks, in his Life of St Werburge (by 1513, printed 1521), to delineate a regional manifestation of early English spirituality as a guarantor of Chester Abbey's spiritual and temporal authority.

However imagined ‘Mercia’ may be, for Bradshaw and others, certain features remain constant. The kingly lineage that extended back through Penda, Icel, and Woden was as ideologically productive as the geographic and onomastic identity of ‘Merci’, ‘the borderers’. Mercian identity and politics coincided with the Welsh Marches, and English marcher lords drew connections between their own position on England's periphery and earlier Mercian liminality. Accordingly, many sixteenth-century Cheshire gentry also identified their palatinate's history with that of Mercia. If to be Mercian is to be set apart from the rest of England, then to adopt a Mercian pedigree is to highlight one's independence from mainstream English heritage and hierarchy – a mainstream increasingly focused, in the early Tudor period, on London and the southern counties.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015