Plant foods are closely connected to cultural, social and economic aspects of human societies, both past and present. Food-preparation techniques and the etiquette of consumption involve complex interactions of natural resources and human cultures. During European prehistory, these changes included the shift to sedentism, the cultivation and domestication of plants, food storage, the production and exchange of alcoholic beverages and luxury foodstuffs, and the continuous adaptation of established culinary practices to newcomers in fields and gardens.

The ERC-funded PLANTCULT Project explores the role of the culinary transformation of plant ingredients in the shaping of social and cultural identities during prehistory, and the contribution of plant foods to social cohesion and differentiation, including the emergence of elites, in daily, communal or special consumption contexts. Our aim is to identify culinary cultures and their transformation over time across a large region, stretching from the Aegean to Central Europe, and focusing on several key sites rich in the remains of plant foods such as bread, beer, oil and wine (Figure 1). Each part of this region presents a different trajectory of social development under influences from the Eastern Mediterranean and Central Asia. We wish to understand the role of culinary practice and innovation in shaping these trajectories; the chosen study area allows us to explore an east-west dynamic at a wide geographic scale.

Figure 1. Study area with key sites. 1) P.O.T.A. Romanou; 2) Limnochori; 3) Angelochorio; 4) Archontiko; 5) Agios Athanasios; 6) Karaburnaki; 7) Mesimeriani Toumba; 8) Dikili Tash; 9) Provadia; 10) Kapitan Andreevo; 11) Vaskovo; 12) Kush Kaya; 13) Sokol; 14) Karanovo; 15) Ada Tepe; 16) Yabalkovo; 17) Kapitan Dimitrievo; 18) Bresto; 19) Mursalevo; 20) Prigglitz-Gasteil; 21) Haselbach ‘Im äußeren Urban’; 22) Stillfried an der March ‘In der Gans’; 23) Roseldorf Sandberg; 24) Seewalchen Sprungturmgrube; 25) Weyregg II; 26) Lenzing; 27) Mondsee Station See; 28) Arbon Bleiche 3; 29) Hornstaad-Hörnle IA; 30) Zurich-Parkhaus Opéra; 31) Delemont/En la Pran; 32) Alle/Les Aiges; 33) Twann; 34) Thunstetten.

An integrated methodology

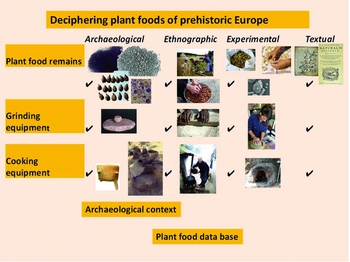

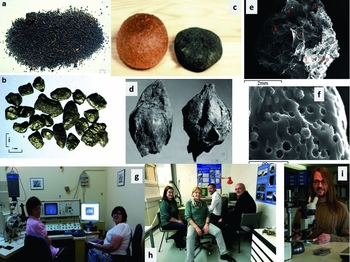

The project adopts an integrated approach that combines plant food remains, processing equipment, ancient written sources, experimental archaeology and ethnography (Figure 2). The remains of food plants, however, form the focus of our investigation. Ancient samples from key sites are being studied in detail and will involve the development of new methodological tools. To this end, a significant body of material (Figure 3) will be examined by stereomicroscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and will be interpreted by comparison with experimentally generated samples. The latter will be created using observations based on archaeological materials, ethnographic records and ancient texts. For example, pilot investigations have explored the effects of food processing, such as grinding and boiling, on grain morphology (fracture surfaces and endosperm structure, e.g. Valamoti Reference Valamoti2002, Reference Valamoti, Moniaki and Karathanou2011; Valamoti et al. Reference Valamoti, Mangafa, Koukouli-Chrysanthaki and Malamidou2007, Reference Valamoti, Moniaki and Karathanou2011). Analyses of the components and production traits of ancient finds of bread (Heiss et al. Reference Heiss, Pouget, Wiethold, Delor-Ahü and Le Goff2015), grape juice extraction and fermentation (Valamoti et al. Reference Valamoti, Mangafa, Koukouli-Chrysanthaki and Malamidou2007; Garnier & Valamoti Reference Garnier and Valamoti2016) and beer-making (Stika Reference Stika2011) demonstrate the need to develop new methodological tools for the effective analysis of archaeobotanical samples. The project will explore microscopic structures (Figure 3e–f) both in the ancient and the modern experimental samples, which will allow for the proper identification of different plant foods in the archaeobotanical record. We will record which plants were used as foods and the ways that they were transformed into meals, and we will explore why specific food choices, both staples and special food substances, such as alcohol and oil, changed over time and what their links were to emerging social hierarchy.

Figure 2. The PLANTCULT Project: an integrated research model.

Figure 3. Examples of ancient plant foods that will be studied by SEM. Greece: a) ground wheat ‘bulgur’ (Mesimeriani Toumba); b) detail of a; Switzerland: c) bread (Twann, 329_1981_82_400_2.jpg, © Archäologischer Dienst Bern); d) grape pressings (Dikili Tash); e–f) Bulgaria: ‘food’ fragments from Kush Kaya (Popov et al. in press); g) SEM work at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (L. Papadopoulou, Tz. Popova); h) University of Hohenheim (S.M.V., A.G.H., H.-P. S.); i) University of Basel (F. Antolin).

As the type and scale of food-preparation equipment are closely linked to culinary practice and socio-economic identities, we will address variability and change in food-preparation technologies by assembling information on stone grinding tools, cooking facilities and pottery, and the plant macro- and micro-remains trapped within them. Associations between cooking, food sharing and alleged household individualisation processes (cf. Halstead Reference Halstead and Halstead1999) will thus be explored. A database of plant food ingredients (Kreuz & Schäfer Reference Kreuz and Schäfer2002), plant foods (ancient and experimental), equipment and archaeological contexts will form the basis for mapping culinary signatures across the study area.

Samples of ongoing work

Archaeobotany and grinding technology (Figure 4)

We will use experimental and ethnographic information to explore the association between plant ingredients, the raw materials used for tools and grinding productivity. The resulting use-wear traces and plant micro-remains will be employed as a middle-range device to explore archaeological finds. They will also form a reference database.

Figure 4. Procurement (T. Dimoudis, N. Kardakos) and manufacture (A. Palomo) of grinding tools for experiments (P. Lathiras, E. Almasidou). Studying use-wear of experimental grinding stones at PLANTCULT headquarters, KEDEK (Centre for Interdisciplinary Research and Innovation, AUTH) (M. Bofill & D. Chondrou).

The interface between beer and wine cultures (Figure 5)

By using archaeobotanical and textual evidence, together with residue analyses, we are exploring beer- and wine-making. The interface between wine and beer cultures will be explored on a wide regional scale; for example, the Mediterranean vs Central Europe. But we will also explore this interface at a regional scale. Taking Greece as a case study, our initial research reveals that assumptions about wine-making and -consumption over the longue durée may be wrong, as archaeobotanical finds indicate Bronze Age beer-making in Greece.

Figure 5. Sprouted barley grains from Bronze Age Argissa Magoula (2100–1700 BC, photographs Lower Saxony Institute for Historical Coastal Research, Wilhelmshaven), Archondiko Giannitson (2100–1700 BC) in Greece, and Hochdorf in Germany, fourth century BC (Stika Reference Stika2011).

Plant foods from prehistory to the present (Figure 6)

The project is also undertaking ethnographic work on specific plant foods that were probably used in the past; for example, split pulses, Grünkern (green-harvested and roasted/smoked spelt) and wine and grape syrup. This will not only inform our archaeological inquiries, but also open the way towards connecting our research with contemporary society and small companies in the food sector.

Figure 6. Collecting modern ethnographic data (clockwise from top left): acorn harvesting at Grevena; winnowing grass-pea on Corfu; making grape syrup at Grevena; making Grünkern (green-harvested and roasted/smoked spelt), recorded by Marian Berihuete Azorín; S.M. Valamoti roasting acorns for experimental foods.

The PLANTCULT Project started in April 2016 and is hosted by Aristotle University with three partner institutions: the University of Basel, the University of Hohenheim and the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Our research will allow us to explore how the powerful sensory experience of food preparation and consumption transformed nature into culture, shaped collective memory and identity, and contributed to the emergence of hierarchical societies across large parts of Europe. In this way, we aim to contribute towards the growing awareness of Europe's culinary heritage.

The PLANTCULT team

The project consists of 47 members (including the principal investigator, S.M.V. and partners S.J., H.-P.S. and A.G.H.). The project postdoctoral researchers are: F. Antolin (University of Basel), M. Bofill, A. Bourliva, M. Berihuete-Azorín (University of Hohenheim), A. Dimoula, I. Hristova, E. Kalogiropoulou, S. Laparidou, M. Ntinou, C. Pagnoux and A. Palomo. The project PhD students are: A. Anagnostoudis, T. Bekiaris, D. Chondrou, S. Michou, D. Nenova, I. Ninou, C. Petridou, G. Prats, Th. Roustanis, K. Symponis, N. Vouronikou, P. Tokmakides and A. Tzelepidou, all based at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki unless otherwise indicated. Project team members contributing specialist advice and material are: N. Alonso, A. Bakalaki, L. Bouby, O. Craig, G. Fiorentino, V. Fyntikoglou, M. Ivanova, A. Kreuz, E. Marinova, C. McNamee, P. Nigdelis, V. Zech-Matterne, L. Papadopoulou, K. Pavlidis, Tz. Popova, S. Prevost-Dermarkar, E. Papadopoulou, M. Primavera, H. Procopiou, J.F. Terral, K. Tokmakides, G. Tsartsidou, Z. Tsirtsoni and S. Vergopoulos.

Further details on the project are available at http://plantcult.web.auth.gr/index.php/en/

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 682529, consolidator grant 2016–2021). The article reflects only the authors’ views.