I ran three laps around my house, preparing and setting my props for a matinee of This Is Not a Theatre Company’s Play in Your Bathtub: An Immersive Audio Spa for Physical Distancing in March 2020. Like much of the world, I was under advisory to stay at home to mitigate the spread of Covid-19, and I was grateful to Erin Mee, the immersive theatre-for-one piece’s creator, for the excuse to take a little time away from my professional and domestic labor to relax in the tub with a glass of wine. I had received an email with an audio file and a props list and was preparing for the performance. Upstairs, in my home’s one full bathroom, I pulled my five-year-old’s bath toys out of the tub to make room for my experience. I turned on the water, waited for it to heat up, and adjusted the temperature. I headed downstairs to the kitchen, where I poured a glass of wine as suggested in the props list; I returned to the bathroom to set it on a ledge where I felt relatively confident it would not be knocked over by a cat. I consulted the props list and dug out a bottle of bubble bath and a washcloth, which I set on the edge of the tub. I checked the bathwater (still running) and looked under the bathroom sink for the one scented candle in the house. It wasn’t there, so I ran downstairs to the half-bath on the first floor and found it in the medicine cabinet. I returned to the upstairs bathroom with what I thought was my final prop, only to realize I did not have matches. I sprinted to the kitchen, retrieved a book of matches from a packet of birthday candles in the junk drawer, and sprinted back to the bathroom in time to turn off the faucet and make my 3:30 p.m. “curtain.” Relaxation, when produced by participating in a theatre-for-one piece at home, requires a fair amount of work.

Between March and May 2020, a number of theatre artists and companies presented interactive performances for audiences to experience alone at home. These were designed to carve out restorative spaces for mindfulness and wellness in the uncertain and stressful times of Covid-19. Besides Play in Your Bathtub, the performances included Entropy Theatre’s Teatime and Pete Danelski and Jordan Clark Halsey’s woolgatherings. Each used different technologies and methods of engagement to create distinct, socially distanced theatre-for-one. Intimate theatrical events designed to be experienced by one audience member at a time have historic roots in 1960s and 1970s avantgarde performance practices and have proliferated in the 21st century (Zerihan Reference Zerihan2020). I use the language “theatre-for-one,” borrowed from Caroline Astell-Burt’s (2017) study of a puppet performance for a single audience member, to differentiate performances that do not include direct interaction with copresent human actors from the theatre practices Rachel Zerihan (Reference Zerihan2020) might call “one-to-one,” which are marked by embodied intimacy and copresent exchange between one actor and one audience member. To access the experiences of a variety of spectators of theatre-for-one, I worked alongside a diverse team of research assistants. Footnote 1 We kept detailed autoethnographic field notes as we experienced performances in our own homes, compared notes across experiences and performances, and made meaning of the patterns that emerged. As participants in performance events Janet Murray would identify as “procedurally authored” ([1997] 2017), we had a great deal of agency within the frameworks set up by the artists in which we could make meaningful choices to shape our experiences. With this agency came the responsibility to cocreate performance events that successfully met the artists’ stated and implicit goals of carving stress-free spaces for mindfulness and restoration. We were not particularly good at this. Our deeply embedded impulses to participate correctly led us to try to do a good job of self-facilitating our experiences, and the labor required to do this contradicted the artistic mission for correct participation to lead us to rest. Had I not worked with a team, I would have thought that this problem was idiosyncratic and personal — two decades of regular yoga practice has yet to teach me to quiet my mind on cue. However, working with a team made clear that this problem reflects the resilience of neoliberal ideologies: we all performed perfectionism even when trying to do the opposite.

These three performances attempted to intervene in an ongoing pattern: many people who have learned how to be productive subjects under neoliberalism do not know how to relax without zoning out in front of a never-ending stream of screen-based content. Play in Your Bathtub, Teatime, and woolgatherings are all designed to help participants resist imperatives to always be productive and their procedures perform anticapitalist values. However, my team found that the only theatrical event-for-one of the three that was able to actualize those values in cocreated live performance was woolgatherings. This work built in social reinforcements to help steer the event in fully restorative directions. Alone, we reverted to habits of (mind centering) productivity and perfectionism. We needed human support and relational care to relax.

Procedural Authorship

Procedural authorship involves “writing the rules” for an interactive narrative world, including designing the performance template inviting audience participation and defining the “conditions under which things will happen in response to the participant’s actions” (Murray [Reference Murray1997] 2017:187). A procedurally authored work consists of both the procedure, the performance template that leaves room for audience participation, and the actions taken by participants in response. Procedures are designed with gaps to be filled and choices to be made, offering participants agency to shape the event with the power to “take meaningful action and see the results of our decisions and choices” (159). In this way, the interactive work is cocreated by the participant’s choices in relation to the procedural author’s rules and invitations. Procedural authors work to define the “horizons of participation” (White Reference White2013), the limits to participants’ involvement, as well as the myriad possibilities within those limits. “Episoding conventions” (Goffman Reference Goffman1974) bracket activity within the frame of the procedurally authored work as distinct from surrounding events and offer cues to help participants identify their roles and the associated expectations. Episoding conventions can be overt, such as when a Forum Theatre Joker offers direct invitations to spect-actors; or implicit, relying upon the audience’s social knowledge of contextually appropriate action in everyday life.

When audience members enter a theatre space for a theatrical event, they enter into an outer theatrical frame (see Goffman Reference Goffman1974; Jackson Reference Jackson1997; Schechner Reference Schechner1973); their actions during or as a part of the performance event are influenced by their preexisting social understandings of the behaviors appropriate for the theatre. These understandings are reinforced socially within the event itself, as audience members witness and respond to each other’s behaviors. Footnote 2 When audience members attend a performance alone, in their own homes, the outer theatrical frame is replaced by an outer domestic frame, which lends itself very differently to participatory performance. Procedural authors rely upon existing social knowledge to guide horizons of both expectation and participation. They design rules and invitations guiding participation with the expectation that participants will share their understanding of what constitutes appropriate or logical responses within the social context of the event. However, prior to the onset of social distancing in response to Covid-19, a number of works were intimate and site-specific, but few asked the audience to experience the event at home. Footnote 3 This presented challenges, as artists and participants did not necessarily share a body of social knowledge on how to engage with a socially distanced performance alone in one’s home. Absent such shared knowledge, it was difficult for artists to predict how a spectator would respond to an invitation to participate in domestic theatre-for-one.

Play in Your Bathtub

When I set my props for Play in Your Bathtub I was in my third week sheltering-in-place. I had my ticket and my husband had agreed to watch our daughter, when at the last minute he was called to a meeting. I booked another ticket for another day — the kind of juggling going on in so many locked-down families working from home. Half an hour before the scheduled performance, my husband and daughter sat down to play a videogame and I ran around the house setting my props, feeling like I was getting away with something by carving out an hour for myself in the middle of the day. I slipped into the steaming bath on a cold, rainy afternoon, letting the tension drip off of my shoulders as I listened to the sound of dripping water and the soothing tones of guided imagery. Playing along to this procedurally authored radio play, I felt the textures of the warm washcloth over my eyes, gave myself a scalp and face massage, explored the taste of the wine on my tongue, danced a duet between my fingers and the surface of the water, harmonized with the audiotrack, explored the textures of the tub with my toes. Play in Your Bathtub is a sensory experience, fundamentally relaxing and pleasant. In the moment of social distancing, which for me was an emotionally exhausting marathon of trying to both parent and work, with limited space to recuperate on my own, this theatre piece was an oasis carving out time to recharge, relax, appreciate my body, and enhance my health. It reminded me that I have the capacity to run a bath, light a candle, pour a glass of wine, and lock the only door in the house with a proper lock. Yet in this experience, I felt guilty lounging in the bath while my husband entertained our child. Even in nonpandemic times, working mothers are assaulted by messages that we should feel guilty for not doing enough (Warner Reference Warner2005). That guilt was part of my experience of the event, as was the feeling that I was getting away with something by drinking wine in the tub.

Figure 1. Props set for Play in Your Bathtub, conceived and directed by Erin Mee. March 2020. (Photo by Dani Snyder-Young)

Bathtub was delivered via an audio file that could be played asynchronously, but the theatrical event was designed and marketed with set performance times to remind participants that we were engaging in a collective act. We were alone, but together. In the “imagined theatre” (Sack 2017) created in the encounter, a chorus of working-from-home-while-homeschooling moms who had been using social media to communicate how they were similarly hanging on by their fingernails could potentially share a moment of solidarity in which the incessant demands of others could be shut off to attend to ourselves for a few moments. This was my imagined connection — I had no idea if anyone I knew was attending that performance on that rainy afternoon. In this imagined theatre, we claim space to resist the dueling priorities of professional and domestic labor that even in ordinary times can squeeze leisure out of the picture.

I later read in the New York Times that Alexis Soloski was similarly taking a break that day from her outpost of “Mommy’s Disaster Montessori” to play in her bathtub at 3:30 in the afternoon, and so she was “there” at that same performance. She documented scalding herself, draining the tub, screaming into the towel, and discovering her undrunk mug of herbal tea in the microwave several hours after the performance. “I am a terrible props mistress,” she confessed. “Relaxation never really hit” (Soloski Reference Soloski2020). Soloski’s experience does not line up with my serene imagined theatre; it does highlight the labor participants take on to self-facilitate procedurally authored solo performances. Soloski took responsibility for the event’s “failure” as due to her lack of skill in props management — a job requiring precision and attention to detail infrequently demanded of audiences in traditional theatre. The responsibility of self-facilitation alongside the friction saturating the working-from-homeschool domestic environment interfered with her ability to achieve the performance’s restorative goals. Her experience of Bathtub cannot be separated from its material context; Soloski is a professional theatre critic wondering what to do during a historic moment when theatres are closed. She attended the performance alongside a number of other theatre-for-one pieces to write an article about them, an act performing the relevance of her job even as many theatre professionals are out of work. It was an overt act not of self-optimization but of professional optimization. I throw no shade on Soloski’s deeply ironic attempt to rest as part of her work — after all, I did the same thing.

Domestic Explorations

Through April and May 2020, Entropy Theatre produced Domestic Explorations, a biweekly series of free procedurally authored performances consisting of prompts in a Facebook group called Entropy Explorers. Research team member Hannah Levinson participated in Domestic Exploration #9, Teatime. Levinson is a white woman in her 20s, and she was sheltering-in-place with roommates in a shared apartment in a large city when she experienced this performance in early May 2020. She found the prompt posted in the Facebook group. It included a set of procedures framed with the instruction “Go through each step one by one, and try not to read ahead” (Entropy Theatre 2020); that the performance would take 10–15 minutes; and that it was designed to be experienced alone.

Levinson proceeded to work through a series of step-by-step tasks to make a cup of tea in a mindful manner, following instructions: “Go to the kitchen or wherever you keep your tea supplies. Put on a kettle for tea. […] Open your tea container of choice, close your eyes, and breath [sic] in the scent. Challenge yourself to identify individual aromas” (Entropy Theatre 2020). Levinson fixated on the use of the word “container,” which to her implied a tin in which one would keep loose-leaf tea. She mentally flagged the phrasing as an odd way to specify required materials; all the tea in her kitchen was packaged in single-serve tea bags. She shrugged this off and followed the instructions, opening a cardboard tea box, taking out an individually plastic wrapped tea bag, and unwrapping it to get a hint of the scent.

Figure 2. Props setup for Teatime by Entropy Theatre. May 2020. (Photo by Hannah Levinson)

At the next step, Levinson balked. She read the instructions, “Look at the tea leaves. What colors do you see? Textures? Symbols?” (Entropy Theatre 2020). She stopped.

Loose-leaf tea may be a kitchen staple in many cultural contexts, but to Levinson it was a luxury product. She started craving a nicer tea, creating shadows of class anxiety that loomed over the performance and operated in tension with the performance’s goals of carving out time for mindful practice. She couldn’t see much of anything within her teabag, and so she attempted to comply with the instructions by ripping her tea bag open and putting its contents in a small sieve she had for the rare, special occasions she had loose-leaf tea around. She looked at the tea, disappointed at the processed, homogenous brown bits in her sieve. She continued to follow instructions, focusing on the sound of the hot water pouring over the tea leaves and the visual shifts of the bits of leaves in the sieve. The heightened attention to her inadequate props led her to fixate on two aspects of the performance: what her performance was lacking, and how her performance might improve if only she could participate in what she felt was the actual procedure as designed.

The performance continued with instructions Levinson could more readily accomplish with her existing props, and she took moments to focus on the smell of her tea, the weight of her cup, the temperature of her tea, the feeling of the tea in her mouth, and the taste of the tea. These procedures focused on the sensory experiences of the activity, and Levinson found herself finally able to start to relax.

Levinson experienced the burden of being both the facilitator and the participant. She felt responsible for not being able to perform the procedure as written when she did not have access to appropriate props. Like Soloski, Levinson experienced challenges in props management, beating herself up for failing to execute procedures perfectly. She was anxious because she was not doing it right, regretted that she could not experience the performance as its creators intended, and felt frustrated that the procedure seemed to be tailored to someone else — someone with a more robust grocery budget or with tastes prioritizing the purchase of loose-leaf tea.

The performance’s goal appeared to intervene in the collective grief and anxiety experienced by many in the pandemic by providing a form of mindful meditation. Entropy Explorers did not invent the practice of mindful tea drinking, but their framing draws attention to how a person can perform mindfulness when they drink tea.Footnote 4 . They situate it as part of Domestic Explorations, a series of performances exploring participants’ domestic spaces in playful ways, attempting to help frequent participants develop a mindfulness practice during a stressful time.

I don’t want to be too cynical; this performance series attracted attention to a fringe theatre company at a time when it couldn’t produce live theatre. As a collective, no individual artists were spotlighted and the larger Domestic Explorations project leans towards radical care resistant to capitalist consumption; it treats procedurally authored wellness as a public and collective good. Nevertheless, the actual language of Teatime demonstrated the ways in which the unspoken conditions present within the participant’s horizon of participation (the hegemonic nature of neoliberalism, the privatization of responsibility, and the capitalist pull of the wellness industry) can turn even the most well-meaning performance into a populist neoliberal configuration of self-care.

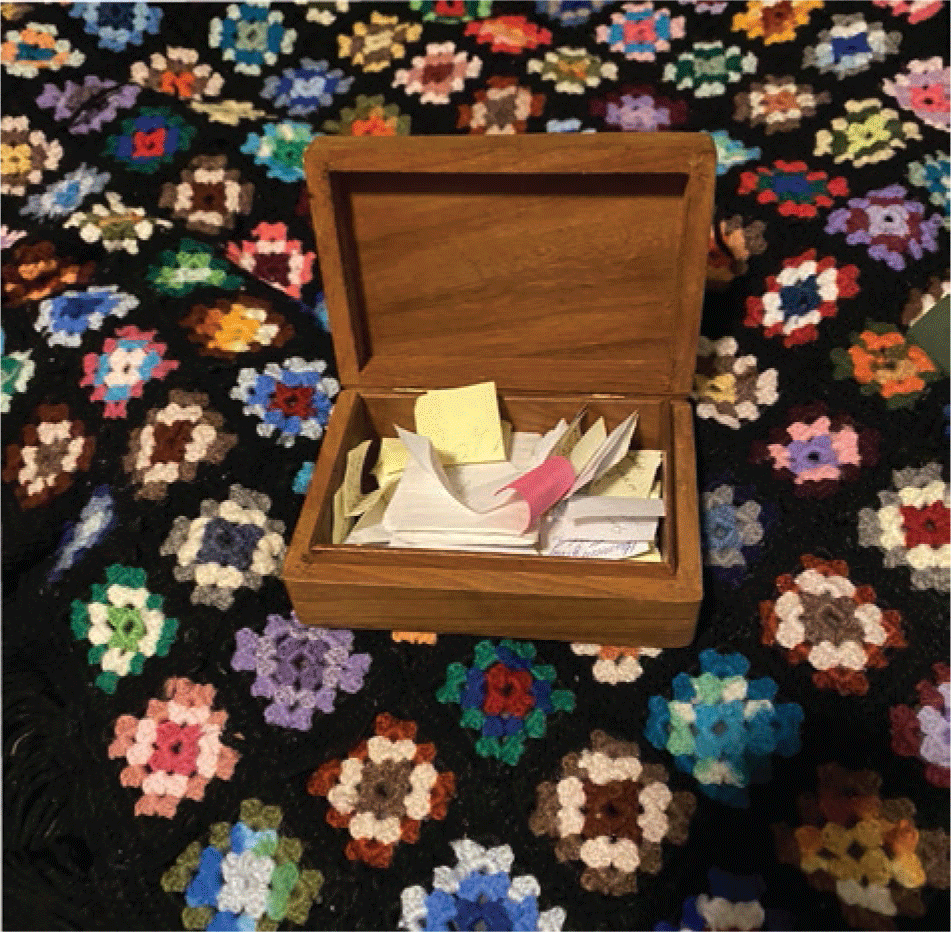

Figure 3. The box of memories Des Bennett shared with Francis in woolgatherings. April 2020. (Photo by Des Bennett)

woolgatherings

Performance Interface Lab’s woolgatherings (2020) was a 20-minute-long, procedurally authored performance designed to allow a solo participant to explore their own memories and their relationship with those memories. Research team member Des Bennett, a biracial nonbinary person in their early 20s, experienced it in late April 2020. They received a call on their cell phone from a facilitator named Dylan who walked them through a process of gathering objects, thoughts, and memories to put into a “hope chest” to share with Dylan’s friend Francis (presumably another participant) over Zoom at the end of the conversation. In the creation of the hope chest, Dylan asked a series of questions, which Bennett documented in their field notes, and asked them to write down the answers to present to Francis at the end of the procedure:

Where is the nearest place for you to get fresh air? Go there and take a deep breath.

When was the last time you said something kind to someone in the space you are in?

When was the last time you made a decision in this room?

Go to a spot where you can see the whole room and describe it.

Go to your bookshelf and run your hand across the books and items on your shelves as if seeing them for the first time. Examine an item that you find most intriguing. Keep it near you.

Is there something in your room that you’ve taken with you everywhere you have every lived?

Sit on the floor, look around your room, and imagine you are very young. Imagine that someone from that time of your life is in the room with you. What would you say to this person?

Bennett experienced an onslaught of memories, as contact with spaces and objects led them on an imaginative journey through their own past, focusing in particular on relationships that had been important to them at different moments of their life. Their father, from whom they had stolen a wooden box, the bookshelf item on which they had lingered. Their best friend from childhood, with whom they longed to reconnect after much time apart. When Marvin Carlson conceptualized ghosting in the theatre as “present[ing] the identical thing [the audience has] encountered before, although now in a somewhat different context” (2001:7), he was not describing the process of browsing one’s own bookshelf. Yet within the framework of the participatory performance, woolgatherings recontextualizes the audience/cocreator’s personal memorabilia and domestic space, activating latent emotional resonances in the familiar by calling up their ghosts. Bennett, like many of us during the months in which we sheltered-in-place, longed to be outside, to be with their friends, to be in a theatre once again, to be anywhere outside of the four walls of their room. woolgatherings’ procedures manipulated each participant’s relationship to their space, reminded them of the residue of real relationships they could find there, and then finally invited them to connect with another human, presumably another audience member who had just undergone a parallel experience of exploring their own space and memories. This brief human connection, mediated through videoconferencing software, offers a reflective cap on the performance, inviting the participant to renegotiate their relationship to their space and memories one more time by reconstructing them in a narrative form they could then share.

Social distancing left many people feeling isolated and lonely. Play in Your Bathtub and Teatime addressed the stresses engendered by social distancing by centering procedures that invited participants to carve out time for solitary self-care. These forms of self-care may not do much to address stresses rooted in feelings of loneliness. Performances like woolgatherings that are performed synchronously by an actor for a single audience member entwine an actor’s artistic production with a participant’s lived experiences to generate a “one-to-one” (Zerihan Reference Zerihan2020) intimacy. Bennett experienced this intimacy with Dylan as care: Dylan gave Bennett time and attention, looking after their needs, working with them to engage their memories and process the emotions that came with them. Bennett was then able to share this experience with Francis within an explicit framework that they were both there to give each other hope in a troubled time, another form of reciprocal care.

Many of the questions Bennett was asked prompted a realization of how objects within their home keep connections with family present. The process of sharing those memories and listening to another person share memories of their own creates a sense of connection. woolgatherings situates the ways in which individuals create, care for, and interact with the spaces they call their own within an “imagined theatre” (Sack 2017), linking them to the spirit of a larger community brimming with care. The brief conversations between participant and actor during the performance do not magically call networks of care into being where they do not exist, nor do they extend relationships created within the framework of the performance beyond the limits of the event. woolgatherings offers a temporary moment of human connection and an invitation to reach out to that childhood friend, to that relative they have been meaning to call, and reactivate dormant relationships. As the Crunk Feminist Collective reminds me, “sometimes we reach the limits of our individual capacity” (CFC 2019:443); in this case sustainable self-care requires collectivity. One-to-one theatrical events are acts of generous collaboration between actor and participant. Such collaborations create moments of human connection, temporarily ending the isolation engendered by social distance. The social reinforcements of the real actor/facilitator seemed to help Des Bennett maintain the practice of mindfulness at the center of woolgatherings.

I succumbed to guilt that I was not doing enough labor to care for my family while Playing in [my] Bathtub, and soothed that guilt by imagining social reinforcements. Relational care and collectivity, even when imagined, helped me and my research assistants resist our own deeply rooted urges towards productivity when we were desperately trying to rest. Socially supportive facilitation removed the responsibility of self-facilitation. Imagined social supports diffused the drive towards self-optimization by claiming that rest, rather than productivity, was the social norm.

Relaxation under Neoliberalism

Our cultural landscape operates within the context of the “attention economy” (Goldhaber Reference Goldhaber1997), in which the onslaught of information made available by the internet leads attention to be a scarce and valuable resource. It is telling that the verb describing the action of directing attention is pay. People “pay attention” within an attention economy. That attention gives power where it is bestowed; attention can be transformed into influence and action. The act of giving focus and energy to the object of our attention is a form of labor (Beller Reference Beller2006; Bueno Reference Bueno2017). Such labor can be pleasurable, but the energy and focus it requires prevent it from being rest. This draws cultural products with restorative goals into tension with themselves. In order to achieve restoration through such products, we must pay attention to them and use them. Such processes make rest productive labor within the attention economy.

Play in Your Bathtub, Teatime, and woolgatherings are all cultural products with goals of encouraging restoration and carving out mindful spaces resisting neoliberal imperatives to maximize productivity. They do this by guiding participants to focus on sensory aspects of pedestrian activities, attending to and interrupting patterns of conditioned behavior (Doran Reference Doran2017; Pagis Reference Pagis2009). Mindfulness is a skill honed through practice, and as such is not a skill all audience members will possess. Responsibility is privatized; paradoxically, the participant must work to reach the desired outcome of relaxation. The emphasis of meditation or of mindfulness within a specific preexisting context — such as taking a bath or making tea — collides with both the participant’s embodied and cultural knowledge of those activities and the material reality of actually performing them. When that collision results in the participant’s inability to reach the desired outcome — mindful relaxation — a kind of user-error message is generated. It is the fault of the user or the participant for failing to participate in the “correct” manner or with the “correct” outcome as defined by the authored procedure.

The procedures at the center of Play in Your Bathtub and Teatime in particular are steeped in preexisting cultural meanings as to what self-care looks and feels like. Although self-care, by definition, includes any practice that an individual engages in to experience a greater sense of wellness within themselves, whether the impact be long-term or immediate, feminist theorists have long criticized the concept for the manner in which capitalist institutions have morphed self-care into a personal commodity that can be bought and sold. This narrow range of activities — baths, yoga, pedicures, deep breathing, etc. — are marketed to target middle- and upper-class women like me, promoting wellness as slim, femme, cisgendered, able-bodied, un-aging, white, and with ample disposable income. Such discourse transforms activities like yoga that can be accessible sites of healing and growth for people of all genders, bodies, races, abilities, and income levels into spaces of “judgement, trauma, [and] oppression” for people whose bodies do not easily conform to those narrowly defined norms (Hagan Reference Hagan2021). Often this populist neoliberal configuration of self-care is oriented towards quick-fix tools to help us to calm ourselves or at least appear calm to others (Michaeli Reference Michaeli2017; Lloro-Bidart and Semenko Reference Lloro-Bidart and Semenko2017). It involves taking time away from the “necessary” duties of professional and domestic labor to recharge, as if we are batteries that run out of energy after a certain amount of use and must be connected to a fresh source of power in order to resume functioning. Time spent taking care of the self must be productive and have a positive result: the ability to more efficiently and effectively engage in paid and unpaid labor. This neoliberal configuration of self-care is “tied to immediate action and to self-preservation” (Martin et al. Reference Martin, Myers and Viseu2015:632), which places emphasis on urgency and on results. In the historic moment in which these performances took place, the usual support structures underpinning daily life were upended by the abrupt closure of many sectors of society. It was a matter of some urgency to be OK enough to get through the seemingly endless stream of paid and unpaid labor the moment demanded. Self-care activities imply a promise: a concrete, short-term practice (if done correctly) will result in an improved and happier state of physical and mental well-being. This is the implicit goal of performances like Play in Your Bathtub and Teatime, and there is a tension between the anticapitalist ethos within which they appear to have been created and the neoliberal ideologies overdetermining their procedures as methods for producing a rejuvenated and mentally stable woman who is able to properly fill her role in society.

The populist neoliberal approach to self-care is rooted in privilege and fails to account for social, economic, and political sources of exhaustion, and its focus on breathing, meditation, and self-indulgence delegitimizes anger as a healthy response. The pandemic amplified preexisting social inequalities; the burdens of illness and economic collapse were disproportionately borne by people already experiencing precarity and social marginalization: people of color, nursing home residents, the incarcerated, frontline health care workers without adequate PPE, people without homes in which to shelter, “essential workers” who prepare, pack, and deliver goods for the consumption of those of us who rarely if ever left our homes, millions of abruptly unemployed — all these people had good reasons to be angry. In the weeks following these three performances, the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin catalyzed the Black Lives Matter movement. Footnote 5 How much can warm baths, hot tea, and deep breaths mitigate the structural forces at the root of much personal and social fatigue and stress? Alternate models of rest as resistance operate within black feminism where a collectivist approach to self-care argues for “resisting and disrupting the individualism that causes much of the harm we experience in society” (CFC 2019:442). Crunk Feminist Collective’s approach is rooted in a network of supportive relationships providing an abundance of resources to navigate commonplace material and emotional stress ranging from childcare to contentious blog posts and job interviews. Is it reasonable to expect people whose financial, emotional, and spiritual resources have been stretched to the limits to find the time and energy to dedicate to self-care? Answering “yes” reinforces a neoliberal value system lionizing self-sufficient individualism. Social distancing disrupts many collective care practices such as shared childcare. The historic moment of the performances discussed here was marked by isolation. At such a moment, social and emotional networks were an essential source of support, able to counter the impulses of guilt and inadequacy that accompanied the research team members’ attempts at restoration.

Rest as Resistance

Exhausted from the work of participating in stay-at-home theatre, my research team ultimately found inspiration in the work of Tricia Hersey, the “Nap Bishop.” Hersey argues for rest as a form of resistance, “disrupt[ing] and push[ing] back against capitalism and white supremacy” (Hersey Reference Hersey2020). Her Nap Ministry, founded in 2016 and rooted in black feminism, advocates for rest in conjunction with collective care as a form of resistance. Hersey’s practice is built on the idea that because of “the psychic remains of slavery” — sleep deprivation among black women and stereotypes conflating rest with laziness — reclaiming time to rest and reconnecting with themselves, their ancestors, and the dreamspace is a way for black women to push back against the white exploitation of black and brown bodies, the capitalist mantra of grind culture, to imagine a new world founded on rest (Hersey Reference Hersey2020). To facilitate this, the Nap Ministry creates sacred and safe space in outdoor or indoor locations for communities to rest together in Collective Napping Experiences. Footnote 6 The Ministry curates restorative napping experiences with yoga mats, blankets, pillows, soundtracks, rest altars, and meditative poetry. Some of these have been framed as performance art, such as Rest (2018), an immersive outdoor performance Hersey created in collaboration with Chicago’s Free Street Theater’s Youth Ensemble, which toured to parks across the city in the summer of 2018 and did not limit participation to women of color. By taking the planning and creating of the experience out of the hands of the participants, the Nap Ministry does the work of facilitating restorative events, enabling participants to simply show up and rest. Hersey emphasizes ways in which individuals of all races can participate in rest as resistance regularly in a myriad of small ways such as staring out the window for 10 minutes, taking long hot baths, or taking a hiatus from social media. Such activities do not require adherence to procedures, careful gathering of props, or scheduled attendance. Performing rest resists capitalist imperatives of constant productivity and self-optimization.

The abrupt closure of many sectors of society in the spring of 2020 was sometimes called “The Great Pause” (Gambuto Reference Gambuto2020; Murray Reference Murray2020). For many people, the scope of everyday life shrank to fit inside their homes; time seemed to slow in the absence of variety to differentiate hours and days. Slow, sensory, meditative activities such as cultivating sourdough starter and baking bread briefly became popular ways for people with the privilege to shelter-in-place. It allowed some who had internalized neoliberal values centering on productivity to both alleviate stress and to experiment with slower, quieter, less consumption-oriented ways of being in a moment better served by sweatpants than pencil skirts. Each of the theatre-for-one pieces discussed in this essay centers on a pedestrian activity one might easily engage in while sheltering-in-place, reframing as performance bathing, drinking tea, and looking around one’s room. Following Hersey’s practice, which was well established prior to the onset of Covid-19, collective events centering these kinds of mindful pedestrian performances could extend such impulses postpandemic to operate as interventions in grind culture.

Artists creating performances with restorative goals address a real need under late capitalism because far too many of us have internalized hegemonic messages privileging individualized self-optimization and productivity over rest and collective care. Prior to the onset of social distancing during the pandemic, theatrical events were primarily defined by live copresence. Experiencing this kind of theatre could be a collective healing, such as performance events designed to support racial healing including Aleshea Harris’s What to Send Up When It Goes Down (2015) and Nia Witherspoon’s Dark Girl Chronicles (2019). Footnote 7 The Covid-19 era has been isolating. Live in-person performances have resumed to some extent, and I hope that as we move forward artists will take advantage of theatre’s collective properties to help us heal. Remote one-to-one theatre like woolgatherings, in which a live actor engages with a live spectator in real time, has the capacity to facilitate mindful reflection on an intimate scale. One-to-one theatre makes the single spectator responsible to a single actor. That bit of social pressure helps the spectator maintain the mindful focus necessary to achieve the performance’s goals.

Participatory performances are spaces in which audience labor is particularly visible because they rely on audience action to cocreate the events, and the personalized nature of theatre-for-one amplifies the idiosyncratic, individualized meaning-making process. Procedurally authored, domestic theatre-for-one requires labor focused on our interior, private worlds. Remote theatre existed prior to the onset of social distancing designed to slow the spread of Covid-19, and it is likely to stick around. Audiences have grown accustomed to consuming culture on-demand in their homes. There is ample space within the burgeoning genre of remote theatre-for-one to help participants grapple with internalized hegemonic messages, including perfectionism, self-optimization, and the fetishization of productivity. That is not rest, but a disruption of internalized hegemonic messages.