It would be difficult to overstate the influence of Hazariprasad Dwivedi (1907–79), who was one of the most prominent literary historians of Hindi and particularly known as one of the chief articulators of the idea of bhakti as a social movement, or āndolan. Dwivedi was also a novelist. His first novel, Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’, holds a place in Hindi literary history that is separate from, but tied to, Dwivedi's contributions as a literary historian. In contrast with other prominent literary historians of Hindi and the classical Sanskrit past, Dwivedi was known as much as a creative interpreter of that past as he was as a critic and scholar. This dual identity is a key part of his memory as having unearthed a ‘second tradition’, as his student and literary critic Namwar Singh frames it. Also, this alternate, popular genealogy for an Indian literary past, in contrast with that of Ramchandra Shukla, was unimaginable without the creative, playful persona of Dwivedi himself: ‘in keeping himself divided, he preserved the creativity which is such a priceless resource for Hindi literature.’Footnote 1

Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ [The ‘Autobiography’ of Bana] plays a crucial role in this conception. As its title implies, the novel presents a fictional autobiography of the seventh-century Sanskrit writer, Bāṇa. It describes Bāṇa's travels from Ujjayini to Harsha's court at Pataliputra, which plays out as a relationship that develops between Bāṇa, an actress named Nipuṇika, and a kidnapped princess, Bhaṭṭiṇī, whom Bāṇa rescues and accompanies to the court of Harsha. The narrative cuts between the story of Bāṇa's relationship with these two women and their adventurous encounters with a range of figures in seventh-century India. Throughout, the text is written in an imagination of Bāṇa's voice that interpolates translations of Bāṇa's Sanskrit text, at times reproducing lengthy paragraphs of description from Bāṇa's most well-known works, the Kādambarī [The Story of Kadambari] and the Harṣacaritā [The Tale of Harsha], and including jokes and references to the commentarial tradition surrounding these and other works. The text is a tour de force—one that displays both Dwivedi's unique mastery of classical Sanskrit as well as his deep engagement with modern Hindi.

Part of the reason for the immediate and sustained reception of the novel—the text has never gone out of print, is frequently included on university syllabuses and exams, and has been the subject of at least one theatrical adaptation—is its uncanny interpretation of an author who, with his innovations in novel-like gadyakāvya narrative and hints of autobiographical writing in the Harṣacaritā, seemed to be the natural choice for Dwivedi's fiction.Footnote 2 Reviews and essays on the novel frequently point out that it seemed so realistically a text of Bāṇa's that it was taken, in a contemporary history of Sanskrit literature, as a long-lost Sanskrit autobiography.Footnote 3 Regardless of the truth of this anecdote, it indicates the success of Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ in producing a voice for the seventh-century poet—and fulfilling a desire, in the aftermath of colonial interpretations of classical literature as decadent and otherworldly, for a modern, autobiographical subjectivity in a pre-colonial literature.

Although Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ was far from the only prominent historical novel of its decade, it was particularly successful because its Bāṇa was such a thoroughly modern, rebellious character—an outsider wandering through the backstreets and underworlds of Sanskrit literature, who is joined by a series of rebellious, progressive women who would be at home in contemporary Hindi literature—and even looks forward to the 1950s characters of Naī kahānī. Criticism of the novel has emphasised Bāṇa's diffidence—a trait often tied to Dwivedi's own puckish personality. Perhaps the most well-remembered quotation from the novel, described by the writer Dharmvir Bharati as ‘a fundamental mantra given to a frightened humanity’, expresses the ability of the novel to root the progressive and reformist ideas of the twentieth century in an ancient past: ‘Fear nothing, neither Guru, nor Mantra, nor the people, nor the Vedas.’Footnote 4 By placing these modern and familiar sentiments in the world of seventh-century India, Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ implants the ideas in a convincing, and complexly imagined, ancient past.

But both those interpretations that praise the fidelity of the novel to Bāṇa's voice and those that emphasise the modernity of its characters and its progressive politics neglect a single fact about the novel that destabilises both points: Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ is presented to the reader as a false document, explicitly created by a European woman. It begins and ends with a brief explanatory note, presented by Dwivedi under the pseudonymous name of ‘Vyomkesh Shastri’, which explains that he was given the document by an Austrian woman named Catherine, who claimed to have had the original manuscript on a trip to the Śoṇa river and translated it herself from Hindi. Vyomkesh Shastri was asked to typeset the handwritten text, which he otherwise presents to the reader unchanged but with the addition of his own commentary. In an afterword, Shastri analyses what he has read, concluding that it had probably been written by Catherine herself.Footnote 5

This lightly presented fact, only gently reinforced by an occasional footnote, upends readings that present Dwivedi's work as a progressive and modern exploration of the classical past. If the fictional conceit of a Sanskrit autobiography is bookended by material that essentially indicates it to have been secretly written by an Austrian Indologist, then the story can no longer be read purely in terms of a progressive and modern subjectivity that can be mined in the ancient past. Instead, it must be read also as a comment upon such an attempt—interrogated, in Dwivedi's text, through the fictional persona of Catherine. The layers of authorial responsibility and intent constituted by the three authorial personas—Catherine, the editorial Vyomkesh Shastri, and Dwivedi himself—make it impossible to take at face value either the exhortation to fearlessness or the perfectly tuned Sanskrit autobiographical voice.

Further complicating Dwivedi's move, there is significant evidence for believing that the character of Catherine is a lightly fictionalised depiction of Stella Kramrisch—one of the twentieth century's most prominent art historians of South Asia. Kramrisch taught at Shantiniketan and Calcutta University from 1922 to roughly 1938, coinciding comfortably with the composition of Dwivedi's novel. Although consideration of this final layer of fictionalisation and authorial uncertainty is not strictly necessary in order to grasp the larger milieu of late-colonial Bengal in which this novel was created, it makes clear not only Dwivedi's deep involvement in the intellectual culture of this period across Sanskrit, Hindi, English, and Bangla, but also the hidden critique of this novel of the genealogies of modern Indology, the foundations of which were arguably being laid precisely at that time in Bengal.

History, the novel, and subjectivity in late-colonial India

Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ lies at the centre of a range of problems in the cultural and intellectual history of late-colonial India; it constellates anxieties of subjectivity and historical consciousness; the status of Sanskrit literature in nationalist discourse; and the complex terrain of northern Indian literatures in the global literary landscape. Although the same could be said of the career of Hazariprasad Dwivedi as a whole, Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ allows Dwivedi, through the multiple layers of subjectivity and authority of the novel, to explore these problems through the medium of the Hindi novel.

The context of colonial historiography and the problem of historical consciousness in India highlight the stakes and accomplishment of Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’. Colonial interpretations of Indian historiography claimed that India lacked not only historiographical traditions, but also a sense of historical consciousness itself.Footnote 6 This idea, which at times presented India as lost in a ‘dreaming’ without historical development itself, coincided with colonialist ideas of civilisation and empire.Footnote 7 This idea only began to be challenged significantly from the 1960s onwards and, in the previous three decades, scholars have begun to investigate instead the ways in which genres, such as the kathā and the caritā, shaped modes of history writing in Indic literary cultures.Footnote 8 From the perspective of the intellectual landscape of the 1940s, however, any such historiographical consciousness was not at all taken for granted; indeed, as many critiques of this problem have noted, figures as late as the 1970s continued to insist that India lacked a historiographical tradition.Footnote 9

Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’, read in the context of the 1940s, intervenes in this intellectual history in several ways. First, as a fictive autobiography, it presents a desideratum of a historical consciousness in the context of a climate in which the idea of its lack had not yet been seriously challenged. Even prior to the recent shift in Indian historiography, Bāṇa's Harṣacaritā was seen as a text that was exceptionally rich in historical detail.Footnote 10 Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’, in extending and deepening the autobiographical voice of the Harṣacaritā, satisfies a intensely felt need for a historical consciousness that elsewhere was expressed in terms of lack.

The book was one of several historical novels from the time, one of which, Rahul Sankrityayan's 1944 Singh Senāpati, featured a similar framing device in which a manuscript was claimed to have been found in an archaeological dig.Footnote 11 But, in contrast with Sankrityayan's work, Dwivedi's novel was read largely in terms of its deploying a very modern plot—with its love triangle and depiction of female desire—within the language and texture of classical literature.Footnote 12 From this perspective, when the character of Catherine was discussed at all, it was in terms of the possibility, raised by the epilogue to the novel, that she was in fact the secret or hidden protagonist of the novel.Footnote 13 As Namwar Singh put it, the voice of Catherine, with her ‘eccentricity borne of emotional vulnerability, structures the entire “voice” of the novel, and, if one listens closely, resounds continually like a quiet echo from behind the stage’.Footnote 14 But, even as critics such as Namwar Singh acknowledge the importance of Catherine as a character to the novel, they do not take into account the interpretation of her authorship for how we understand the text and its comment upon Indian historiography. Instead, they ultimately see it as a part of Dwivedi's larger project of reassessing the history of Indian literature.

Framing Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ from the point of view of the instability and ambiguity of this document, however, raises questions of authorship, subjectivity, and genre that frame it as only an ‘experimental’ novel, even as it engages with the national–traditionalist framework through which it is often received. Most prominently, a false document raises the issues that are most prominent in the discussion of Bāṇa's work: the autobiographical voice visible most prominently in the Harṣacaritā and the prologue to Kādambarī that made Bāṇa's work a touchstone in the search for a historical discourse in ancient literature. The rise of the early novel in South Asia, in fact, coincided with the translation into Bangla, Hindi, and other South Asian languages of the Kādambarī and the Harṣacaritā, and the Kadambari became so associated with the form that it lent its name to the Marathi name for the novel itself.Footnote 15 The ambiguous status of Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ presents a solution to this problem—through a found document that would fulfil the hopes of an autobiographical self—even as it undermines those hopes through presenting it as clearly false.

Finally, the fact that Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ is not only a fictional found document, but also one written by a lightly fictionalised Stella Kramrisch asks us to consider how the novel intervenes in both the orientalist scholastic traditions of which Kramrisch is a representative as well as the historical context of Shantiniketan and Bengal during the late-colonial period. Part of the memory of Dwivedi, in Hindi, emphasises the importance of his time at Shantiniketan working with Tagore; indeed, in many ways, he is remembered as a bridge not only to the ancient past, but also to Bengal and its modern literary heritage.Footnote 16 Not only the false authorship of Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’, but also its authorship at the hands of perhaps the most prominent non-South Asian art historian to emerge from this milieu ask us to consider the uncertain and complex heritage of orientalism itself—that is, the intersection between colonial modernity, the rediscovery of the ancient literary past, and nationalist discourses that made use of that past. But, to better understand that, it is important to recognise the complex biography and lengthy career of the ultimate author of the novel, Hazariprasad Dwivedi.

The intellectual milieu of interwar Bengal across language

Hazariprasad Dwivedi is, after Ramchandra Shukla, the most prominent and important literary historian of the Hindi language, although, like Shukla, his influence is somewhat obscured in English-language scholarship. Recent research has highlighted Dwivedi's role in the formation of a nationalist historiography of a bhakti movement and the importance of his scholarship on Kabir.Footnote 17 Hindi-language scholarship, however, reveals Dwivedi's formative influence and position at the centre of institutional power in Nehruvian India, including a contentious period of chairship in the Department of Hindi at Benares Hindu University (BHU) and a series of institutional affiliations throughout the rest of his life. From these influential positions in post-independence India, Dwivedi defined the parameters of Hindi's literary past, most prominently by revising Shukla's historiography of Hindi from one centred on an ‘inward turn’ following the establishment of Muslim rule towards attention on literary changes rooted in what he considered a popular ‘movement’ of bhakti.Footnote 18

Prior to his later institutional power, Dwivedi's early biography and career at Shantiniketan are essential to his reception in Hindi, creating the image of Dwivedi as a bridge between both a modern, progressive humanism and a vast, approachable picture of the literary past. Dwivedi was born in Balliya district, in today's eastern Uttar Pradesh, to a rural Brahman family. After studying Sanskrit and specialising in jyotiṣa, or astrology, at the then newly formed BHU, he took up a position as instructor of Hindi at the then newly formed Viśva-Bhārati university at Shantiniketan—a choice that surprised his family given his background as a village Brahman and further education in Sanskrit.Footnote 19 He would teach at that unique institution for the following 20 years, before returning to BHU as the head of its Hindi department in 1950.

Dwivedi's time at Shantiniketan is most often depicted in terms of his relationship with Rabindranath Tagore, which Dwivedi characterised as a life-changing event that he frequently remembered as a romanticised relationship between guru and shishya.Footnote 20 Namwar Singh has characterised the influence of Shantiniketan as not only bringing Dwivedi in touch with Tagore's ideas on bhakti, but also pulling Dwivedi away from the literary debates in the main literary centres of Hindi, and therefore laying the groundwork for Dwivedi's departures from the historiography of Ramchandra Shukla.Footnote 21 Dwivedi's position at Shantiniketan was seen to insulate him from the politics of language with which Hindi was associated. Although there are limits to such a claim—Calcutta, ultimately, was firmly within the orbit of the Hindi sphere, as shown not least by Dwivedi's frequent publication in the Calcutta-based journal, Viśāl Bhārat—what Singh describes as the ‘strange contradiction’ of Dwivedi's distance from ‘contemporary traditions of Hindi criticism’, which resulted in works such as Kabīr and Hindī sāhitya kī bhūmikā [An Introduction to Hindi Literature], can be attributed in part to the intellectual trends at Shantiniketan.Footnote 22

Singh also notes, in passing, that Dwivedi's move to Shantiniketan brought him into a distinct cosmopolitan context.Footnote 23 The unique environment of Shantiniketan, however, was the foremost example of what Kris Manjapra has termed ‘Swadeshi internationalism’: an effort to develop channels of international exchange and education separate from British empire.Footnote 24 These exchanges, especially in the case of German-speaking expatriate academics, provided one of the most important alternatives in late-colonial India to the British imperial world. Even as Tagore himself turned away from a Swadeshi-era idea of practical cultural development in favour of a transcendental model of culture as sanskriti, the context of Shantiniketan, and Bengal more broadly, was one in which the study of ancient India was redefined through new efforts to think through an essential India-centred international world.Footnote 25

Because of its complex relationship with the national movement, Hindi is primarily seen in terms of the discourse and contradictions of its own self-definition.Footnote 26 In part, this means that a work such as Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ is often read, in Hindi literary history, solely as a historical novel, removing its complex depiction of seventh-century India from debates over historicity. But this reading, even as it does not account for the careful engagement of the novel with problems of historical voice, also obscures the ways in which Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ was in fact deeply engaged with its context of late-colonial Bengal in ways that are fundamental to the construction of the text.

Among the most prominent figures who were, in Manjapra's formulation, ‘entangled’ with Indian intellectuals during the interwar period, Stella Kramrisch stands out at the intersection of Indology, modernist art, and the cultural institutions that surrounded Rabindranath Tagore.Footnote 27 As I will argue later, there are compelling reasons to think that the character of Catherine in Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ is a fictionalised version of Kramrisch but, even without this fact, her biography would exemplify the cultural milieu of interwar Bengal intellectual history and underscore Dwivedi's attempts to bring its tensions into relief in his novel.

Born in what was then Moravia to an Austro-Hungarian family and raised primarily in Vienna, Kramrisch arrived at Shantiniketan in 1923, principally through the intercession of Tagore himself after training with both Josef Strzygowski and Max Dvořák at the University of Vienna. She quickly shifted from Shantiniketan, where she was one of the first instructors at Viśva-Bhārati, to the University of Calcutta, where she would remain as faculty until 1948. There, she came under the influence of the Tagores and the school of modernist Indian art referred to as ‘The Bengal School’. After she left Calcutta University and took up her role as curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, she became increasingly associated with the perspective of Ananda Coomaraswamy, who is credited with defining the modern parameters of Indian art as inherently metaphysical and rooted in textual traditions beginning with the Vedas. This perspective, however, was already visible in her two-volume work, The Hindu Temple, released in 1946, the same year as Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’.Footnote 28

Stella Kramrisch, who helped to organise the Bauhaus exhibition at Calcutta, was at the centre of what Manjapra argues was a network of German and Austro-Hungarian intellectuals engaged with India.Footnote 29 In the 1930s and 1940s—the period during which she most likely would have been in contact with Dwivedi—Kramrisch was increasingly moving away from the methodology of her teachers in favour of an increasing influence of Tagore and Coomaraswamy. Whereas Strzygowski emphasised a radicalised, civilisational history of art that highlighted India's connection with Central Asia and Northern Europe, as opposed to a derided Greece and Mediterranean, Dvořák developed a historicist view of Indian art as developing over long periods of time from a civilisational impulse.Footnote 30 The combined influence of the Tagores and Coomaraswamy, meanwhile, emphasised an idea of Indian art that explicitly rejected mimesis and pictorial realism in favour of a metaphysical harmony that relied upon religious ideas about reality. As I will show, there are possibilities that these influences are directly portrayed in the narrative of Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’. They also demonstrate the ways in which Kramrisch, at the centre of these various evolving trends, is an essential figure in understanding the internationalism of the period.

Although I have not discovered any direct evidence that Stella Kramrisch is the model for the character of Catherine, circumstantial evidence is compelling. Kramrisch was born into a prominent Austrian family in what is today Czechia but was at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian empire; much of her childhood, in fact, was spent in Vienna. Although the only direct knowledge of her language skills relates to her Sanskrit, from which she translated several texts, given her long time living in Calcutta, Dwivedi's characterisation of her further language skills is reasonable. The novel refers to her primarily not as Catherine, but as dīdī—the familiar Bengali term for an elder sister by which Kramrisch was frequently addressed.Footnote 31 A final small detail is her lifelong love of cats, described in Barbara Stoler Miller's biographical essay as well as attested to through the archives of her life, which include countless pictures and even a letter from the 1930s in which she describes adopting stray cats while living in India.Footnote 32

For these reasons, a conclusion that Catherine is at least in part based on the real-life Stella Kramrisch seems justified. More important than the proof of a connection between these two figures, however, are the implications of its possibility. Why might Dwivedi have chosen to frame his pseudo-biographical narrative around one of the most prominent female Indologists of her time? How might Kramrisch's interests, given her prominent opinions on art history, play into Dwivedi's goals with the text? And how, finally, might considering Stella Kramrisch within the space of Hindi literary culture open our perspective towards new frameworks of understanding the Hindi novel, its approach to autobiography, and its imagination of the world?

To consider these problems, I will now turn towards the narrative itself and the way in which it constructs the character of Bāṇa. As my reading will show, Bāṇa's character, which is often read in terms of its construction as a modern, novelistic figure, is consistently interpolated with the works of the actual Bāṇabhaṭṭa through a citational practice that invites the reader to compare the novel with the original works and steadily undermines the authorial authority that the novel seems to be producing. The result is that, especially when considering the suspected authorship of the novel, the seemingly ‘realistic’ autobiography voice is revealed in Dwivedi's larger structure to be an unstable, if essential, presence.

Shifting voices of authority

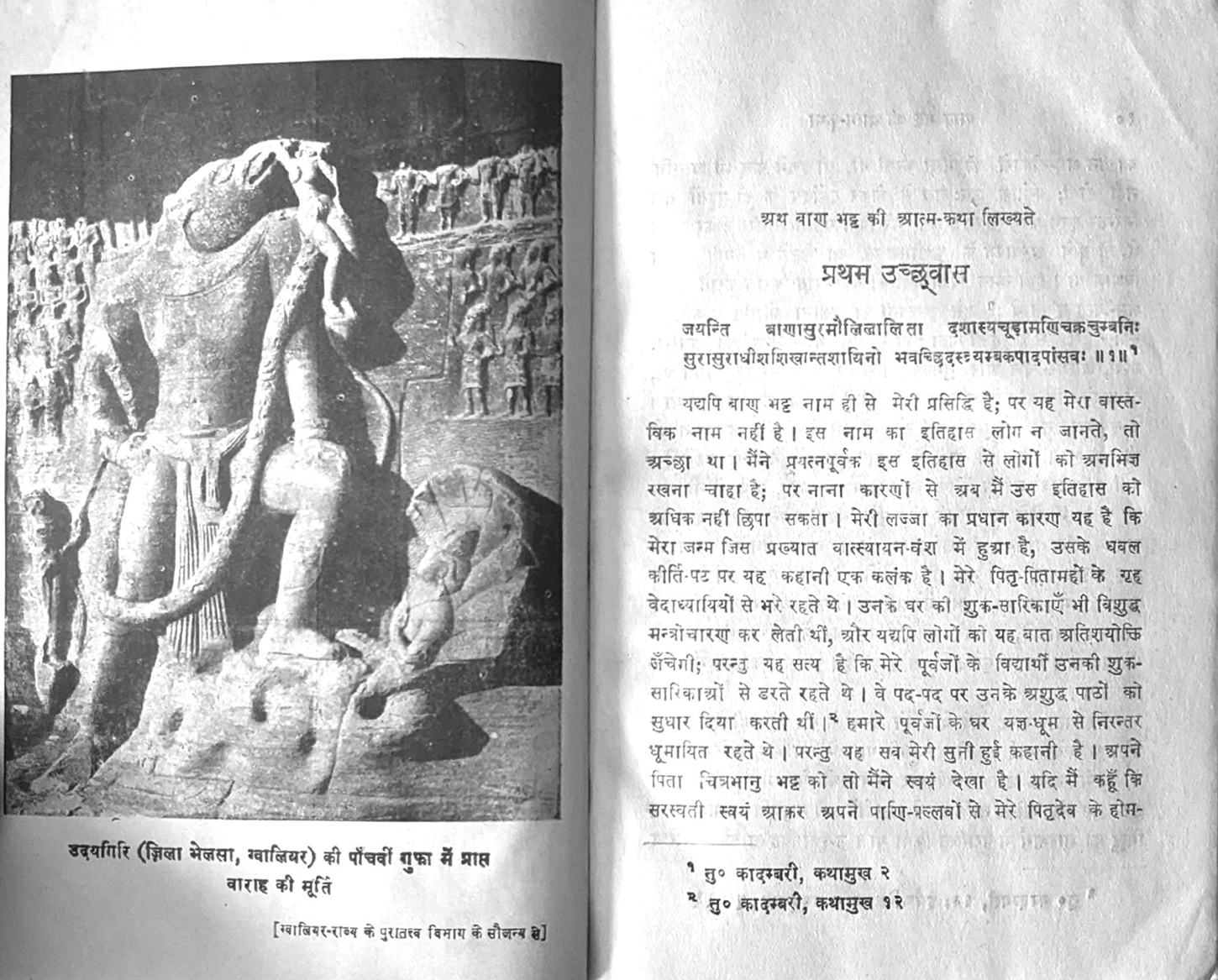

Although Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ was serialised from 1943 in the Calcutta weekly, Viśāl Bhārat [Expansive India], it was first published in 1946 by the author himself.Footnote 33 The front cover is dominated by a line drawing created by Kripal Singh Shekhavat from a photograph of the famous Udayagiri statue of Mahāvarāha.Footnote 34 In the drawing, Varāha has lifted Earth, personified as a young woman, on his tusks; the story of Varāha, and the worship of Varāha as an implied early form of bhakti, is a prominent theme of the novel. A reader might naturally consider this image to simply be an appropriate nod towards the historical context of the story—one that emphasises the milieu of post-Gupta India in which the story takes place.

This cover is the first indication that Dwivedi is drawing our attention to the complicated status of the novel. The simple line drawing—which, like the apostrophe marks around the word ātmakathā, was removed from later additions—is followed, after the preface, by the inclusion of the photograph from which it was traced (Figure 1). By including them together, the drawing emphasises the processes of documentation, transcription, and revision that are at the core of the novel. Kripal Singh Shekhavat's line drawing at first seems like a simple sketch of the photographed site, but closer attention reveals that it both adds to and subtracts from the sculpture, as shown in the photograph. The sketch removes the rows of small figures behind Varāha, shifting from the three-dimensionality of sculpture to an iconicity and focus on Varāha. In addition, whereas the actual sculpture as shown in the photograph is damaged, with the top of Varāha and the Earth goddess missing, the sketch imagines a complete, undamaged whole. Next to the photograph, the line drawing becomes a tracing—a further gesture towards mimesis, but one that is immediately rendered as suspect when placed next to the greater verisimilitude of the photograph. At the same time, the privileging of the line drawing on the cover, with its evocative emphasis on the movement of Varāha and the relationship between the divinity and the helpless, vulnerable humanity held up in its tusks, provides an argument against photographic realism. Considering the larger structure of the novel, one can therefore see the contrast between sketch and photograph as raising the questions of authority.

Figure 1. The original cover of Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’. Source: original text.

The reader would view, in order: the line drawing; a page of acknowledgements, which includes a credit to Kripal Singh Shekhavat; a preface by the fictional Vyomkesh Shastri; and, facing the first chapter of the main narrative, an image of the actual sculpture at Udayagiri. The inclusion of the photograph after the preface but prior to the main story binds these elements into a narrative whole, moving from an interpretive drawing to the mimetic realism of the photograph. The preface, therefore, is given a place of authority as leading the reader into the ‘real’ world of the autobiography. The preface, similarly, in presenting to the reader what it claims is a faithful reproduction, in print, of a handwritten text enacts the same technological transformation. But, as the sharp distinction between the photograph and the interpretive drawing indicates, the multiple technologies and modes of authorities that frame this story produce—and, I would argue, are meant to produce—readerly suspicion, not only of the text itself, but also of the larger structure of Indological knowledge that claims to deliver it.

Following a page of acknowledgements from Hazariprasad Dwivedi, the novel begins with a preface by Vyomkesh Shastri. Dwivedi's alter ego has long been a source of fascination for Hindi criticism—Namwar Singh devotes a chapter to him in his Dūsrī paramparā kī khoj, arguing that Vyomkesh Shastri is a way for Dwivedi to transcend the restrictive expectations of Sanskrit scholarship.Footnote 35 Here, however, posing as Vyomkesh Shastri, Dwivedi also emphasises the fictive structure of the novel; unlike the actual author, and like the narrator Bāṇa himself, Vyomkesh Shastri is not totally aware of what is happening, and only slowly and fitfully discovers the true structure of the novel.

The preface begins by introducing Catherine as ‘at the unmarried daughter of a respectable Christian family of Austria’—an enthusiastic Indologist who learned Hindi and Sanskrit, and came to live in India for eight years. The Catherine of Vyomkesh Shastri's account is, in economic terms, a lively, complex character, far from a one-note joke or a pastiche of a European orientalist. In fact, from the first moments of Catherine's introduction, Dwivedi seems to dwell on the ambivalent relationship between Indian scholarship and the wealthy European Indologists who were responsible for such a great deal of primary research. When Catherine—whom Vyomkesh Shastri refers to as ‘Dīdī’, elder sister—returns from a fieldwork trip with various historical objects, she would be surrounded by a crowd of admirers, eager to see the objects. Dwivedi's description of this event presents Catherine in what at first seems like an innocent joke:

Didi would pull out objects one by one and, placing them in our hands, tell us their histories. As she did this, her throat seemed to tighten up and her little blue eyes grew moist; then, slowly, a white kitten would come out of her pocket, all scrunched up. We knew the joke. To make Didi happy one of us would enthusiastically take the kitten as if it was some fragile manuscript. And then the kitten would jump up and we would leap back as if astonished. Didi would laugh hard enough to shake the roof off the cottage. One consequence of all this fun was that, when she wasn't looking, someone would snatch one of her priceless artifacts (although I never did such a thing!) and Didi would have no idea. At times, when Didi went into a state of concentration … it was as if Sarasvati was manifest before us.Footnote 36

Catherine, in her enthusiasm for the objects that she has acquired in the field, becomes overcome with emotion. To lighten the mood of her rapturous, unmediated encounter with these texts and objects, she then pulls out a small kitten—something she has apparently done several times before. As the unnamed mass of presumably Indian students and scholars surround her and pretend to laugh at her joke, they slip into her pockets and steal one of the objects that she has collected. The vignette stages the long history of colonial orientalism as a farce in which the German enthusiast, oblivious to empire, shifts into a state of meditation. By this logic, the Indian tradition of Indology, which might frame itself as rightfully taking control of national history, is placed from the start into a suspect position of inheritance. It throws into relief the tensions inherent in Dwivedi's own scholarly identity just one year prior to an independence in which a new Republic of India would lay claim to the symbolic apparatus of ancient India—a process in which Dwivedi himself would play a central role. Catherine's rapturous presentation of her objects is undercut by her ignorance of how they are actually received. Her admirers are presented to the reader as a cynical, anonymous mass and the text shows no interest in their interpretation of these objects. The passage, even as it foreshadows the plot of the text through its depiction of Catherine's devotion, also cautions the reader not to accept the manuscript itself at face value.

After returning from another trip—this time to the area around the Śoṇa river in central India—Catherine presents a manuscript to Vyomkesh Shastri, asking him to it have typed and printed in Calcutta. This manuscript, she claims, is a Hindi translation of material collected from the area, which is cited in the Harṣacaritā as the homeland of Bāṇa's Vatsyayana line. The manuscript, accordingly, begins with atha bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ātmakathā likhyate—a macaronic combination of modern Hindi and Sanskrit that translates as ‘Here is written the autobiography of Bāṇabhaṭṭa’.

Although Vyomkesh Shastri is overjoyed at the scholarly implications of the text, there are several reservations: for one thing, when Vyomkesh meets with Catherine, he is told by her servant that she had been in meditation the previous evening until two in the morning, at which point she began to write continuously for six hours. When Vyomkesh asks her about the contents of the manuscript, she replies: ‘The days of my life have slipped away in mere shame and hesitation, those days when I had the strength to work. Now in my old age I've neither the enthusiasm nor the strength. And you—lazy.’Footnote 37

Catherine's story hints at some personal untold tale. Her reference to ‘shame and hesitation’, too, indicates some of the themes of the novel, which will frequently focus on the actress Nipuṇika and her relationship with Bāṇa, and describe her own feelings of shame and hesitation towards a relationship with him. Later, in the epilogue to the story, Vyomkesh Shastri will begin to suspect that Catherine may have had a deeper involvement with the creation of the manuscript, but that is only hinted at in the prologue. The effect overall, however, is one of a suspicion towards authorship throughout the claim that the text is portraying the autobiographical voice of the Sanskrit writer.

Undermining authority

In the original edition of Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’, a photo plate on the left-hand page depicts the statue of Varāha lifting Earth that I contrasted earlier with the line drawing on the cover (Figure 2). On the right-hand page, the first line of the narrative that follows is: ‘Although my fame rests solely upon the name Bāṇabhaṭṭa, it is not, in fact, my actual name.’Footnote 38 This initial statement indexes both the plot of the narrative—in which Bāṇa, and most of the other characters, go by multiple names—as well as the larger narrative structure: the ‘real name’ of the person writing the text is also not Bāṇa, but Catherine.

Figure 2. Photograph of the Udayagiri sculpture of Varāha in Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’. Source: original text.

The autobiographical introduction that follows interweaves multiple biographical sources from Bāṇa's works into a new autobiographical voice. In doing so—complete with careful footnoting from Vyomkesh Shastri—the text encourages the reader, at the outset, to compare these older sources with the contemporary text before them. It teaches the reader to parse the subtle differences between the autobiographical voice of the ātmakathā and the cited Sanskrit evidence of Bāṇa's own works:

It would be better if no one knew the history of this name. I have tried my best to keep it hidden, but for several reasons I can no longer conceal it. The main cause of this shame is that this story forms a black stain on the shining vestments of that esteemed Vatsyayan lineage into which I was born. The homes of my father and forefathers were always filled with the sounds of Vedic study. Even the mynahs and starlings of those homes could pronounce them perfectly, and although this may strike some as hyperbole, the students of my forefathers truly did fear those birds. On every line, they would correct any mispronunciation.Footnote 39

At this point, a second footnote refers to the twelfth stanza of the benediction of the Kādambarī, which features an almost identical description of students who are corrected by birds.Footnote 40 Comparing the narrative text with the citation from the Kādambarī reveals several crucial differences between the two. What in the Kādambarī is presented in poetic verse without comment is in the narrative preceded with an acknowledgement that it may seem hyperbolic to some. What is a trope of the genre in the Kadambari is a cause for authorial self-reflection, pulling the reader back into the metadiscursive space of the novel itself. Dwivedi was aware of the difference—in a separate piece comparing the Kadambari and other gadyakāvya with the modern novel, he writes:

Ringing resonance [jhaṅkār] may be the life [prāṇ] of poetry, but it cannot be the life of the novel; because it was the natural development [upaj] of that pure [viśuddh] era of prose and in its nature [prakṛti] prose had an organic [sahaj] natural flow [pravāh]. The fundamental difference between those tales and accounts [kathā-akhyāyana] and this new limb of truth [satyāṅg] lies in their goals [ādarśgat]. The goal of the novel is personal liberty [vaiyaktik svādhīnatā], that specific gift of the mechanical age [yantrayug]–and the goal of tales and accounts is the predetermined and traditional good conduct [pūrvanirdhārit aur paramparāsamarthit sadācār] of the age of kavya.Footnote 41

Dwivedi sees the primary difference of the novel in its emphasis on personal freedom rather than reinforcing social norms. Dwivedi's statement, at first, would not be out of place with other contemporary statements associated with progressive literature, such as Premchand's famous speech to the inaugural meeting of the All-India Progressive Writer's Association, which framed premodern literature, and especially premodern story literature, as inherently unconcerned with reality.Footnote 42 Unlike Premchand, however, Dwivedi emphasises a link between the thematics and social commitments of the novel and the stylistics of the prose-tale. Leaving aside whether this is actually what Kādambarī and other prose works do, this is the contrast formed in these opening pages. By including a self-referential anxiety to Bāṇa's voice and inviting the reader to compare it with its cited source, it underlines the differences in sensibility and subjectivity between them.

Signs of this narrative subjectivity appear throughout the narrative, often at key points of interpolation. In one passage, for instance, Bāṇa watches a procession on the birth of a prince, drawing its language directly from that of the Kādambarī, which itself is using a set piece that can be linked at least to the Buddhacaritā in which royal woman are ecstatic at the sight of the young prince. But, at the end of a long passage filled with a complex, heavily Sanskritised language, the narrator notes that ‘[t]he procession lasted for two daṇḍa, and I stood the whole time, staring at the splendour of it’.Footnote 43

The statement of time at the end of the piece is significant not only because it was not present in the original source material from which the description taken, the Kādambarī, but also because the notice, and the mentioning of the exact time, is considered a hallmark of the modern novel. Attention to clock time is a trope in a wide range of nineteenth-century novels and other works of realist prose.Footnote 44 By placing this line prominently at the end of the passage, Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ underlines its difference from the Sanskrit textual tradition that it is supposedly mimicking.

Similar moves are played out throughout the narrative in which an interpolation of text drawn directly from a work of Bāṇa is counterpoised by Bāṇa's own comment in such a way as to underline the gulf between the two. That each of these moments is usually accompanied by a footnote that cites the original text reinforces this: the reader is recruited into a textual–critical practice of reading the difference between the Sanskrit text and the modern commentary.

Thus, throughout the slowly developing narrative of Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’, the artificiality of the enterprise is underlined again and again. At certain moments in the text, however, this artificiality shifts into a different direction, as Bāṇa engages in a form of criticism that brings together the fictional world of seventh-century India with that of the late-colonial milieu of Dwivedi itself. At these moments, Catherine emerges as a major figure in the narrative. Furthermore, these instants also bring to the foreground the critical capacity of the text, through its unstable layers of authority, to question the epistemology of knowledge of ancient India that enables its creation.

The plot of Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ takes its characters on a long journey from the palaces of Ujjayini to, at the conclusion of the novel, the imperial court of Harsha. While the intricate plot, with its range of historical detail and imagination of the social world of seventh-century India, is beyond the scope of this article, a key exchange is particularly helpful in exploring the intersection between authorship, critique, and fiction in this text.

Before the narrative leaves Ujjayini, Bāṇa visits a prince and is given a small hand-sized statue of the Buddha. Receiving the statue leads Bāṇa into a long impromptu reflection on aesthetics:

It was an idol of the Buddha carved of black stone. The artist had filled statue, only the width of a hand, with a strange beauty. I do not like at all those Gaṅgā-Yamunī statues prepared in this country in Indian and Greek styles by the Śakas in their zeal for Buddhism [Buddha-bhaktī ke āveś meiṃ]. They contained neither an idol's depth of meaning and spirit, nor any geometric skill [ve na to mūrttī ke arth-puruṣ kī gaharāī meṃ jātī haiṃ, na prameya-pāṭav meṃ]. On the one hand they had the style of the Greek idols—of meaningless obsession over the measurement of limbs—and on the other, ignored the symbolic meaning [vācyārtha] of the gestures [mudrāoṃ] in favour of their figurative indication [vyangyārtha].Footnote 45

This passage juxtaposes an interpretation of Bāṇa's voice with a distinctly historiographical perspective. But whereas in the previous section, Bāṇa's own language is subtly interpolated into the autobiographical voice, here Bāṇa speaks in the language of art history, taking up the contemporary discourse of Indian art in ways that evoke not only the twentieth century, but also the work of Stella Kramrisch herself, who, early on, juxtaposed a caricature of Greek art, with a rigid attention to bodily proportion and mimetic realism, with an Indian art more attuned to an idea of essence. Kramrisch, whose The Hindu Temple would be published in 1946, was developing at this time her theory of Indian art as primarily oriented around a metaphysical, internal essence, rather than an attempt at mimesis.Footnote 46 In well-known articles such as her 1935 ‘Emblems of the universal being’, she developed a theory of the ‘subtle body’ that focused in particular on depictions of the Buddha.Footnote 47 In this account, ‘[t]he substance of the Buddha image exceeds the semblance of bodily limits’ in ways that go beyond realistic depiction.Footnote 48 Kramrisch's use of the example of the Buddha relied upon a distinction between Hellenistic and indigenous artistic traditions that is precisely paralleled in this passage.Footnote 49

Bāṇa critiques Buddhist art in terms of its proportion and lack of attention to ‘symbolic meaning’. He then proceeds to praise the figurine in ways that further echo Kramrisch's argument. Kramrisch, for instance, describing the clockwise curled hair in depictions of the Buddha, wrote that ‘[t]he craftsmen did not rigorously adhere to this aspect of the symbol. They had more comprehensive means at their disposal to form the substance of the Buddha’.Footnote 50 Bāṇa would use similar language to praise the figurine:

This sculptor had made such a statue that the viewer might think the Buddha was truly sitting there. The eyebrows above his half-closed eyes were not made with the crookedness of a squirting jet of water, but rather were shaded in such a way that they did the work of the bridge of the nose. The fingers of the hands were absolutely natural. In fact, there was a not-too-distant relationship to the statues of the Gupta era. There is a difference between meditation and sleep. Most of the Kuśan statues did not even allow one to remember this distinction, but this statue seemed with its great vigour to be showing its wakefulness in every pore.Footnote 51

It is reasonable to acknowledge that Kramrisch's approach to Indian art, as it developed over the 1920s and 1930s, owed as much to her interactions with other intellectuals in Bengal as to her own innovations. Indeed, Kramrisch's concept of an essential metaphysical background to Indian art and her thesis in The Indian Temple that the temple should be understood in terms of Vedic religious beliefs was common in nationalist conceptions of history. But the precision of this critique in drawing from Kramrisch's work attracts our attention to the ways in which Dwivedi might be deploying the voice of Catherine in his construction of Bāṇa's personality. That role, in its intermingling of voices that is emphasised throughout the text, might be read, again, as mere conceit. But the afterword of the novel takes up all these issues and makes it clear that Dwivedi understood exactly what he was doing in framing the manuscript in the way that he did.

The international stakes of the ancient past

Following the narrative, which has been laden throughout with footnotes that indicate Vyomkesh Shastri's independent scholarship and fact-checking, he adds an afterword that directly addresses the concerns that he claims he has. Here, Shastri engages directly in a form of literary criticism rooted in his understanding of genre and the differences between Sanskrit prose literature and the realism of the twentieth century:

Bāṇabhaṭṭa's autobiography ends here. Clearly, it is unfinished. It occurred to me that an investigation could not be limited simply to comparison with Bāṇa's other extant works, but rather would need to be read in terms of its own inner literary qualities. At first glance the style of narrative seemed very similar to that of the Kadambari; it has the same dominance of vision as opposed to the sensory faculties [indriyoṃ]—form, color, grace, beauty [rūp kā, raṅg kā, śobhā kā, saundarya kā]—here too they are all massed together in description; but this alone does not complete literary analysis. The attentive and sympathetic [sahṛdaya] reader will feel that the writer, when he began to write, was not yet aware of the entire incident at hand. The story is written in the style of todays ‘diary’. It seems as if the writer is binding events to text [lipibaddh] as they move forward. Where the intensity of his emotions grows intense his writing becomes condensed; but, where the waves of sadness grow higher, his writing becomes slack and depressed [śithil]. In the final chapters it seemed as if he was slowly drowning inside himself. This seemed strange to me; this style of writing is unheard of in Sanskrit literature. All this also began to seem suspicious [sandehjanak].Footnote 52

In his alter ego as Vyomkesh Shastri, Dwivedi presents a critique of his own text that also functions as a critique of the novel as a genre and its difference from the gadyakāvya of Kādambarī. For Dwivedi, the key distinction is narrative; even as Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ presents the same visual language as the works of Bāṇa, it departs from the narrative style precisely in the autobiographical voice that is so crucial to Bāṇa's modern reception. The diary-like pace, emotionally influenced subjectivity, and sudden shifts in expression are fundamental to this text, to the point of suspicion.

With this piece alone, Dwivedi establishes a central portion of my argument: that the structure of a found document is central to any understanding of this text and that it is intended not only to place an autobiographical voice in the milieu of classical Sanskrit literature, but also to interrogate the possibility and stakes of such an action. At this point, however, Dwivedi's alter ego continues to discuss the differences between this text and its source, but does so in terms of the depiction of love and gender:

One more thing. In the Kadambari, there is a kind of pride [dṛpt bhāvnā] in the expression of love; but in this story, the suggestion of love is put forth with a feeling of depth and pridelessness [prem kī vyañjanā gūḍh aur adṛpt bhāv se prakaṭ huī hai]. It seems as if expression is blocked everywhere by a humility common to women [strī-janocit lajjā]. There is throughout the story forceful and logical support for the greatness of women. Only this obscure and prideless love could be the natural culmination of the way the story begins. From the point of view of the natural development of the story itself, this does not seem like a fault of obstruction; but, in Banabhatta's writing one is bound to expect a more clear and prideful expression. And then, in the place of all those twists and turns of physical love [prem ke jin śarīrik vikāroṃ]–of emotions, of flirtation, of fresh and unmechanical adornment—we find that the twists and turns of the mind—of humility, of inertia, of rootedness—are far more common. All of this, too, stuck at me. I had resolved that I would explicate all these things—with examples.Footnote 53

Dwivedi's continued critique opens a range of interpretive possibilities, some of which would require closer analysis of the text itself. But, whereas his analysis begins with a discussion of narrative pace, now it shifts into the emotional terrain created by that pace: what would be presented with pride and even arrogance is instead presented with humility, with the autobiographical voice capable of expressing emotional relationships that would seem to be outside the scope of Bāṇa's works. But, just as Shastri is about to write his commentary, he receives a letter from Catherine:

You printed ‘Bāṇabhaṭṭa ki Ātmakathā’; good job. Even if not as a book, how is it any less to have it printed in a journal?Footnote 54 I can now count the days I have left in this world. Before I die, don't print this letter I have written about the ‘story.’ I don't think I'll be able to join you all again; I am truly renouncing the world. This is my final letter.Footnote 55 You made one great mistake in dealing with the ‘Ātmakathā.’ You presented it in your prologue as if it were an ‘auto-biography.’Footnote 56 My goodness! I had always thought you had studied Sanskrit, but what kind of foolishness is this? The ātmā of Bāṇabhaṭṭa is present in every grain of sand in the Sona river. What ignorance—can you not hear the voice of this ātma? Look at you—you're a man, you're young—this kind of helplessness doesn't suit you.

That ill-fated cat has given birth to a whole platoon. So many bombs have fallen in this war, and not one of those devils has died. Who knows how long I'll be able to take care of them. In life, what's gone is gone—just like raising that cat. But I have only complaint for you, which I doubt you will understand. You fool, ‘Bāṇabhaṭṭa’ is not found in India alone. From the world of men to the world of kinnaras Footnote 57, a passionate [rāgātmak] heart is everywhere. Did you ever even try to understand your didi! Helplessness, laziness, and haste—avoid these faults. Now your didi can't rush over explain all these things to you. One neglect in life—one mistake—is a wound that will burn and torment you. My blessing to you is that you'll escape from these things.Footnote 58

Here, Catherine takes up the same cautionary tone as she used in the prologue, but she is now more explicit in her concerns. Speaking from the middle of the Second World War, the fictional Catherine seems to be warning Vyomkesh Shastri against a kind of poverty of interpretation that would reduce the complexity of Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘Ātmakathā’ to simply the ‘autobiography of Banabhatta’. If we read this letter in contrast with Vyomkesh Shastri's earlier analysis, Catherine can be seen as critiquing a suspicious reading that is more interested in proving or denying authorship. Catherine insists that Bāṇa should be seen universally—‘a passionate heart’—and not limited to the historical figure of Bāṇa. Her letter therefore acknowledges her own likely authorship of the text, even as it critiques the entire goal—arguing instead, perhaps, for a reading beyond the question of authorship altogether.

Shastri, for his part, seems unable to grasp the implications of Catherine's letter in anything but the most literal sense. He begins to think that Catherine must have written the story herself—something that he seems to have begun to think already, judging from his earlier evaluation—and concludes that she must have been placing herself in the role of Bhaṭṭiṇī. His reasoning, in a pun that closes the novel, is that, in the story, Bhaṭṭiṇī claims to have grown up in the fictional ‘astriyavarṣa’, just as Catherine is an ‘Āsṭriyā-deśvāsinī [resident of Austria]’.Footnote 59

Conclusion

The epilogue to Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ asks its readers to return to the prologue, to consider again not only the character of Catherine, but also the entire structure of the novel. Dwivedi's careful reading and distinction of the narrative form of Bāṇa's voice essentially refuse the ‘suspension of disbelief’ that would later be attributed to the character of Catherine. Vyomkesh Shastri proposes, prior to writing Catherine, to present his own analysis—one rooted not solely in comparison, but through the internal qualities of the text. The tragedy of the novel, perhaps, is that this analysis is never carried out and Vyomkesh Shastri leaves his readers with a suspicion that Catherine was Bhaṭṭiṇī and that the novel was itself the result of a story from Catherine's personal life. In so doing, Vyomkesh Shastri forecloses the possibility of further analysis—but in such a way as to make it clear that such analysis is warranted.

The conclusion of the novel, in its letter sent from a war-torn Austria, raises the stakes of this analysis and opens up the consideration of the concerns of the novel with contemporary India on the eve of independence. The international atmosphere of Shantiniketan and late-colonial Calcutta, and the European roots of the Indology that underlie this text, come together in this final moment. Unlike Stella Kramrisch, who was at this time still a refugee in India, Catherine has fled to her native Austria. But the insecurity and anxiety of her position make clear the ways in which the character of Catherine, and ultimately the story of the autobiography itself, is bound up with the fraught, violent landscape of late-colonial India in the Second World War.

These interpretive possibilities would require a deeper consideration of the intellectual context of interwar Bengal—one that brought together at a minimum scholars working primarily in Hindi, Bangla, and English, and saw simultaneous developments in art history, the study of Sanskrit literature, and ideas of folk culture that would go on to be crucially important in post-independence India. For instance, Dwivedi's experiments in the formal structure of the novel have only been considered in terms of contemporary Hindi, despite the distinct influence of the Bengali novel noted by literary critics.Footnote 60 Further study could take into account not only novelists who were widely read in Hindi such as Sarat Chandra Chatterjee, but also writers, such as Dinesh Chandra Sen, Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay, and Hemendrakumar Ray, who are less canonised in Hindi literary history but who, whether by presenting a ‘romantic’ interpretation of literary history in the case of Dinesh Chandra Sen or experimenting with questions of history and narrative form in the case of Rakhaldas Bandhyopadhyaya and Hemendrakumar Ray, could be read as important influences on Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’.Footnote 61 Hazariprasad Dwivedi would form an ideal subject for such a study because, among the major literary historians of Hindi, he is consistently seen within Hindi-language critical scholarship as the figure most eclectic and widely engaged with literatures outside Hindi.

The layers of fictive, unreliable narration that make up Bāṇabhaṭṭa kī ‘ātmakathā’ therefore function as more than a satire of modern Indology, even as they lend themselves to such an interpretation. As the epilogue to the novel makes clear, the fictional framework to this story makes possible a deeper, richer reading of this text—one that sees its remarkable construction of Harsha's India as bound up with the complex inheritance of knowledge of India produced during the colonial period. The possibility that it has engaged with the character of Stella Kramrisch as Catherine therefore can be seen as a gesture towards both the antinomies of this inheritance as well as its continually generative creative possibilities.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the two anonymous readers, who offered detailed and useful feedback. The author would also like to thank Darielle Mason, the Stella Kramrisch Curator of South Asian and Himalayan Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, for her helpful advice regarding the project; and Kristen Regina, Arcadia Director of the Library and Archives of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, for her assistance in working with the detailed archives of the museum.

Conflicts of interest

None.