1. Introduction

Human communication is constantly evolving as a consequence of its own use, so that linguistic variation is an inevitable phenomenon within and between language communities. Linguistic variation has two sources: from within a community, or outside it.

When a language community is isolated from other communities, it still undergoes internal structural changes. This isolation can come about as a result of geographic location, but it can also result from lack of social integration, or from distinct language identity and attitudes, even when speech communities are geographically proximate.Footnote 1

The external source of linguistic variation is referred to as language contact.Footnote 2 As Britain and Thomason explain, types of contact between languages can vary from global media forums—both written and oral—to the small and local scale of everyday conversation.Footnote 3 Whatever the nature of language contact, individuals from different speech communities can induce changes in each other's language usage; and, if these changes are internalized by other individuals, they can result in convergence at the community level, that is, the reduction of differences between two linguistic systems.Footnote 4 While most studies of language contact in Iran focus on the interaction and evolution of linguistic structures,Footnote 5 a few also reflect on the impact of social context and its relation to structural changes in a systematic way.Footnote 6 However, the “ecology” of language, which also acknowledges the determinative role of geography as part of a larger system of change, has been consistently overlooked.

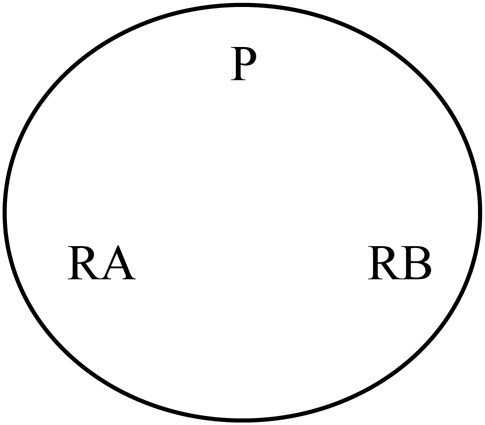

Raji (autonym: rạyeji / rạži) is a Central Plateau language in the IranicFootnote 7 family which is spoken in Kashan district, in the north-west corner of Esfahan Province, Iran. In this paper, we look at the language situation of Raji from an ecolinguistic perspective, which emphasizes linguistic behaviour and structures as part of a larger geographic and social system.Footnote 8 Specifically, we investigate patterns of Persian influence on two Raji dialects, those of the towns of Abuzeydabad and Barzok, near to the city of KashanFootnote 9 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Geography and location of Abuzeydabad and Barzok relative to Kashan, Esfahan Province, Iran (background map from google.com, © 2018)

The city of Kashan, at just over 300,000 residents,Footnote 10 is the cultural and economic centre of the region. Known for its ornate mirrored mansions, radiant handwoven silk carpets, and the production of rose water, it is one of the great historical oasis cities of the Iranian plateau.Footnote 11

Persian has been spoken as the dominant language in Kashan for many centuries, but another language was likely spoken prior to the New Iranic period.Footnote 12 The existence of a distinctive language that persisted in one sector of the city until recently and remnants of the traditional Central Plateau language in surrounding citiesFootnote 13 suggests that the original language of Kashan itself was in fact Central Plateau. Kashani Persian, as still spoken by most Kashani residents over sixty years of age, retained some (primarily lexical and phonological) features of the original language and innovated some structures of its own.Footnote 14 However, even this derivative urban Persian dialect has been almost completely replaced among middle-aged and younger speakers by the contemporary Persian spoken norm based on spoken Tehran-type and ketābi (formal or written) Persian but still with a discernable Kashani flavour.Footnote 15

Borjian observes that, in the towns around Kashan, including Barzok and Abuzeydabad, a shift from Central Plateau to Persian emerged several decades ago and has accelerated recently. Nearly all those who continue to speak Central Plateau are fully bilingual in Persian.Footnote 16 Interestingly, the particular variety of Persian spreading from Kashan to its satellite settlements is contemporary Persian rather than the city's older dialect.Footnote 17 The present article opens a window into this historical process, and how it is taking shape across the Raji language area around Kashan.

Our initial analysis of the two dialects reveals contrasting patterns of contact-induced change from Persian influence. What are the reasons for these differences? The towns of Abuzeydabad and Barzok have similar populations (both around 5000 people), and are found at a similar distance (about thirty kilometres) from the nearest urban centre, Kashan.

In section 2, we introduce the Raji language, and more specifically the varieties of Abuzeydabad and Barzok, in the context of work carried out on the Central Plateau languages of Iran. Section 3 introduces our methodology and gives an overview of the data we collected. Using structural analysis of contact-induced change as a starting point, with a focus on lexicon and historical phonology (section 4), we then examine their contrasting paths to convergence with Persian and probe the geographic and social factors that have led to separate outcomes for each of the dialects (section 5). A more detailed overview of Abuzeydabad and Barzok is provided in that section, in the context of analysis.

2. Raji in the context of research on Iran's Central Plateau languages

Important works which attempt to give an overview and provisional classification of Central Plateau languages, despite uneven documentation, are those of Krahnke, Lecoq, Stilo, and Windfuhr.Footnote 18 A majority of Central Plateau varieties are located in Esfahan Province. These varieties are shown in the map by Talebi-Dastenaei et al.Footnote 19 in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Geographic distribution of Central Plateau varieties of Esfahan Province, Iran (from Talebi-Dastenaei, Borjian, Anonby, et al., in the Atlas of the Languages of Iran (ALI). This map is freely available under an Attribution-Only licence (© 2022, CC BY 4.0).

Raji has been classified within the North-East division (also referred to as the “Northern-Central group” or “Raji group”) of the Central Plateau languages, themselves part of the Northwestern branch of the Iranic languages.Footnote 20 The North-East division of Central Plateau is itself constituted by dialects in and around Kashan (Judeo-Kashani, Dehi “village language” of the Kashan area, Old Ārāni, and Bidgoli), the Natanzi group of dialects to the south-east, the Maymai group of dialects across the mountains to the south-west and related varieties to the north across the border with Markazi Province,Footnote 21 and Raji itself, with dozens of distinctive dialects, at the geographic centre of the group.Footnote 22

The geographic extent of Raji “proper” has only become clear gradually, and consensus regarding its precise delimitation has yet to be reached. In a survey of language distribution in Esfahan Province, Talebi-Dastenaei et al. found that the Central Plateau varieties in and immediately around Kashan do not refer to their language as “Raji,” even if they share some areal similarities; in contrast, speakers’ use of this term for their heritage language was observed to be strong in and around the towns of Barzok, Abuzeydabad, Qohrud, Abyāneh, Bādrud, and Jowshaqān, but weaker to the south toward Meymeh, Natanz, and Ardestān.Footnote 23 This lines up in many ways with the gradient, isogloss-informed delineation of Raji proposed by Borjian, with the exception that Borjian shows that, for the features he investigated, the dialect of Bādrud does not clearly pattern with the other Raji varieties in his study.Footnote 24 Mahnaz Talebi-Dastenaei and colleagues continue to work on delineating the geographic extent of use of the label rạyeji/rạži, and investigating the linguistic integrity of these varieties, in the context of the Atlas of the Languages of Iran (ALI).Footnote 25 A summary map of the Raji language area as currently understood, showing the locations of varieties discussed here, is provided below in Figure 3 following a descriptive synopsis of this language group.

Figure 3. Approximate delimitation of the “core” Raji language area, based on Borjian (2012b, p. 46),Footnote 52 with Barzok (RB) added. The delimitation of the Raji group is not fully resolved, especially along its southern edges.

The earliest work on Central Plateau languages, carried out by an assortment of scholars in the late 1800s, was collected in the Grundriss.Footnote 26 Most of the studies in this volume featured the Central Plateau varieties of Nāin, Sivand, and the Zoroastrian language of Yazd. Zhukovskiy, also consulted there, described an assortment of varieties from across the North-East division of the family, including the Raji dialect of Qohrud, which he first indicated was known to its speakers as rāyeǰi.Footnote 27 Separately, Browne also collected a list of twenty-five words and several dozen short sentences from Qohrud.Footnote 28

Other important studies on Central Plateau were carried out in the early 20th century by Mann, Christensen, and Bailey, examining the dialects of Natanz, Gaz, and Soh, to the south of the core Raji language area, but did not consider any dialects of Raji proper.Footnote 29

Lambton, who referred to Raji as a “Persian” dialect, provided a short introduction to the Raji dialect of Jowshaqan (o Kāmu), located toward the western periphery of Raji.Footnote 30 Her linguistic sketch included vowel and consonant inventories and provided paradigms for eleven verbs. This section was followed by a ten-page transcription of a conversation in the language.

We are unaware of any further research on Raji varieties in the period leading up to the 1970s.

Until now, the most significant cross-dialectal works relating to Raji are those of Krahnke and Lecoq, who in the early 1970s both carried out field research on the Central Plateau languages. Krahnke undertook a dialectological survey, primarily classificatory in nature, of twenty-eight language varieties across central Iran, including the Raji dialects of Abuzeydabad, Jowshaqān (o Kāmu), and Bādrud.Footnote 31 Lecoq's fieldwork focused on nine varieties of the region (perplexingly labelled as “kermanien”), and mostly belonging more specifically to what would become known as the North-East division of Central Iranic.Footnote 32 His grammatical sketches of selected varieties (AbuzeydabadFootnote 33 and AbyānehFootnote 34) were followed up by a comparative article in the Compendium.Footnote 35 Eventually, in 2002, he published a comparative grammatical description of all nine varieties—among them the Raji dialects of Abuzeydabad, Qohrud, and Bādrud—accompanied by several hundred pages of transcribed oral texts. Despite the fact that the two scholars were working on languages of the same area at the same time, they did not cite each other at the time of the first publications, perhaps still unaware of each other's work. In Lecoq's comparative chapter, he finally incorporates Krahnke's findings, but again in 2002 excludes these from his comparative grammar.Footnote 36

Also beginning in the 1970s, Iranian scholars have turned their focus toward research on a number of Raji varieties.Footnote 37 At that time, Purriāhi laid the groundwork for broader documentation through his detailed survey of the linguistic geography of the Raji language area, although it was not published until later.Footnote 38 Yarshater surveyed grammatical gender in eighteen North-East Central Plateau varieties, including several Raji varieties, and mapped them out in relation to Kashan.Footnote 39

Subsequently, in addition to the dialects of Abuzeydabad and Barzok, which are the focus of this paper and to which we will return shortly, descriptive studies have been undertaken on the Raji dialects of Jowshaqān o Kāmu,Footnote 40 Qohrud,Footnote 41 Bādrud,Footnote 42 and Nashalj.Footnote 43 Hamidi-Madani and Maleki studied verb systems in Raji, but did not specify the source dialects for individual data.Footnote 44 In the third volume of the Ganjineh “treasury” of the dialects of Esfahan Province, Razzāqi brings together comparative data from an area that includes many of these Raji dialects.Footnote 45 Finally, in a summative article, Borjian establishes and maps out a comparative overview of the Raji area.Footnote 46 He shows that a bundle of fourteen isoglosses patterns together for Raji dialects to the south of Kashan, with gradually decreasing similarity further away from this geographic core. Our own summary map of the Raji language area (Figure 3) is inspired by Borjian's map.Footnote 47

The dialect of Abuzeydabad is the best-documented of all Raji dialects. As mentioned above, the first documentation was carried by Lecoq and Krahnke.Footnote 48 This was followed up by Lecoq's comparative article in which the dialect was mentioned,Footnote 49 and eventually his comparative grammatical overview and collection of oral texts.Footnote 50 Yarshater produced a concise but seminal article on verbal and nominal systems, with a focus on gender in the latter.Footnote 51 Other scholars have followed with similar works on the verbal systemFootnote 53 and nominal system.Footnote 54 Razzāqi focused on grammar more widely through several papers.Footnote 55 Mazra'ati, and Mazra'ati and Razzāqi compiled dictionaries of Abuzeydabadi.Footnote 56 Razzāqi also wrote an article comparing morphological classes in four Raji varieties, namely the dialect of Abuzeydabad alongside the dialects of Barzok, Totmāj, and Qohrud.Footnote 57 Distinctive morphological features discussed there include ergative-absolutive alignment in past tenses and grammatical gender in some of the varieties. Finally, Esmā’ili and Aslāni examined anaphoric reference in this dialect.Footnote 58

For the Raji dialect of Barzok, a few cursory descriptive linguistic studies are also available. In a more general book on geography and culture, Jahāni-Barzoki provided a brief historical and sociolinguistic overview of the dialect as well as a few samples of vocabulary and proverbs.Footnote 59 Sādeqi contributed a chapter to the Varzānāmak, with collected observations on sentence structure, verb alignment, and lexicon.Footnote 60 Talebi-Dastenaei and Anonby inventoried the basic lexicon of this dialect.Footnote 61 Haghbin et al. wrote an article on word order typology.Footnote 62 Sanāati and Talebi-Dastenaei documented interpersonal and experiential metafunctions in narrative text in Raji of Barzok.Footnote 63

To this point, none of the published research on Raji has provided in-depth comparisons between dialects of the language, and the miscellaneous character of the data gathered and the scholarly descriptions of these data do not allow for systematic comparison. Further, no studies have yet examined the extent of Raji's contact-induced language change and shift toward Persian, and the factors driving this process.

The present study therefore seeks to fill this gap in the literature by comparing and analyzing a parallel set of linguistic data from the dialects of Abudzeydabad and Barzok, and considering the role of social and physical geography in the language's ongoing decline.

3. Methodology and data

In preparation for analysis and comparison of linguistic structures, we conducted a survey of non-linguistic factors in this language situation. Mahnaz Talebi-Dastenaei has resided in Kashan for over fifteen years and participates in social networks (kinship; professional, educational, and acquaintance networks; travel) that radiate out into the surrounding region, and are particularly strong in relation to the communities of Barzok and Abuzeydabad. It was this unique vantage point that brought the nature of the particular linguistic ecosystem described here to her attention. As a participant in these language communities,Footnote 64 she observed, inventoried, and analyzed salient non-linguistic factors in the language situation over a three-month period in 2018. In keeping with the methods and categories proposed by Bastardas-BoadaFootnote 65 and Ehrhart,Footnote 66 we have divided these into geographic and demographic considerations, patterns of mobility, and other major factors such as language identityFootnote 67 and diffusion of mass media.Footnote 68

The content for our language contact analysis is drawn from linguistic data collected from the dialects of Barzok and Abuzeydabad, prior to the survey of non-linguistic factors, over a two-month period in early 2018. We consulted one speaker from each dialect for the in-depth research: a 64-year-old retired schoolteacher from Barzok and a 40-year-old schoolteacher from Abuzeydabad. Both consultants were born in their present community and have lived most of their life there, learning Raji as a mother tongue and gaining fluency in Persian at an early age. The linguistic data and subsequent analysis focus on lexicon but also touch on phonology and grammar. Data were collected by Talebi-Dastenaei using the 323-item JBIL Iranic adaptationFootnote 69 of the CoBL/IE-CoR questionnaire,Footnote 70 and audio-recorded as a .wav file using a Sony ICD-PX470 handheld recorder.

One obvious limitation in methodology and results relates to use of a questionnaire/elicitation format with Persian as the stimulus language. This format will inevitably result in accommodation to Persian structures, especially given the speakers’ high level of bilingualism. Secondly, in this initial study, we worked closely with only two representative speakers of the language. In order to understand the degree to which our findings can be generalized for each community, it will be necessary to work with a cross-section of speakers from each dialect, representing diversity in age, gender, and other social characteristics. That said, despite its limitations, our contextually-informed comparative study is the first of its kind in the Raji language area. It combines linguistic expertise with an emic (insider) perspective, and is the first linguistic description of data from the dialect of Barzok in particular. In this way, this study makes a meaningful contribution to the literature.

4. Patterns of structural similarity

In any language contact situation, patterns of contact-induced change can be identified through analysis of structural similarities between varieties. In the present study, long-standing dominance of Persian over Raji is a likely scenario for many cases of structural similarity. However, it is not the only one. Raji, like Persian, is an Iranic language. While the two languages are not closely related—with Persian belonging to the Southwestern branch of Iranic,Footnote 71 and Raji identified as a distinct dialect groupFootnote 72 most often placed within Northwestern IranicFootnote 73—there are many similar (and sometimes even identical) structures that underline the shared ultimate origin of the two languages.

Here, in order to deduce patterns of contact-induced structural change, we will proceed with comparisons of Persian (P), Raji of Abuzeydabad (RA), and Raji of Barzok (RB). Theoretically, five basic patterns of similarity are possible when any single feature is compared:

-

Pattern 1: all three languages share a feature

-

Pattern 2: the two Raji dialects share a feature that differs from Persian

-

Pattern 3: all three languages exhibit distinct features

-

Pattern 4: Persian shares a feature with Raji of Abuzeydabad, but not Raji of Barzok

-

Pattern 5: Persian shares a feature with Raji of Barzok, but not Raji of Abuzeydabad

Without an accompanying principled analysis of historical structural change, as established by the comparative method,Footnote 74 the first three patterns give minimal insight into the workings of contact-induced change: Pattern 1 (all three share a structure) could be the result of shared inherited structures; Pattern 2 (Persian differs from both Raji varieties) could simply be a reflection of historical distance between Persian and all Raji varieties; and Pattern 3 (all varieties are distinct) simply highlights the reality of structural change over time in any or all of the three varieties. However, cases in which one Raji variety shares a structure with Persian but not with another Raji variety are likely to point to Persian influence on that first variety (Patterns 4 and 5).

In fact, all five patterns are attested in the data—some more strongly than others. In addition, an unexpected sixth pattern has emerged, where lexical content and phonological forms in Raji of Abuzeydabad are structurally intermediate between Persian and Raji of Barzok (Pattern 6).Footnote 75 This situation could be schematized as follows:

-

Pattern 6: Raji of Abuzeydabad exhibits features which are structurally intermediate between Persian and Raji of Barzok

In the following discussion, we will illustrate and analyze each of these patterns. This will be followed up with a second major section in which we seek to identify the geographical and social factors that have led to the particular patterns of convergence that dominate in the data.

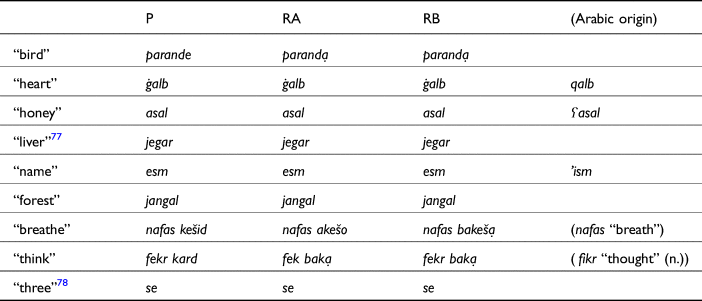

Pattern 1 (strong): Persian and both Raji dialects share many structures. Persian and both Raji varieties share many lexical, phonological, and morphosyntactic characteristics. In the lexicon, many of these similarities can be straightforwardly attributed to shared inheritance. Examples of shared words which may be inherited are as follows (Table 1):

Table 1. Inherited words shared between Persian and the two Raji dialects

Other shared words are more likely reflective of Persian borrowing into both Raji varieties (Table 2). Sometimes, this can be deduced from the fact that a particular item is not as widespread as an inherited item across Iranic, as in the case of P parande “bird” (and possibly P jangal “forest”). In other cases, the words are ultimately of Arabic (not Iranic) origin, and it is reasonable to assume Persian borrowing from Arabic during the early New Iranic period as an intermediate stage in the adoption of these words into Raji. Although it is beyond the scope of this paper, we acknowledge that systematic historical/comparative analysis can be an important means of helping identify and situate loanwords, especially in the case of (even distantly) related languages such as Persian and Raji.

Table 2. Words shared between Persian and Raji dialects through borrowing

The fact that almost all the phonemes in both words sets here are identical among the three varieties confirms a significant level of shared inherited phonological content and similarities among all three phonemic systems. There is also a high level of phonemic equivalence and stability when words are borrowed from Persian into Raji.

Although the JBIL listFootnote 79 is not specifically tailored to analysis of morphosyntax, the prevalence of light verbs constructions in all three of the varieties (e.g., noun + verb for “spit” (v.), “breathe” and “think”) highlights a deep familial, or at very least areal, link in morphosyntax for the three varieties. In the sections on the following patterns, there are numerous further examples of light verb constructions in the three varieties.

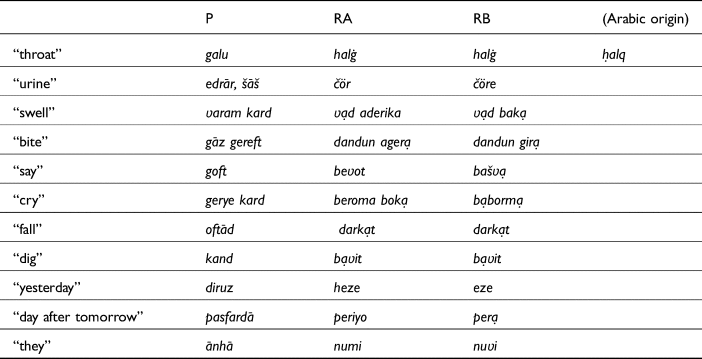

Pattern 2 (strong): The two Raji dialects pattern together against Persian. In a second pattern, also dominant, the two Raji varieties share features which are not found in Persian. Table 3 shows some examples from the lexicon:

Table 3. Words shared between the two Raji dialects but not characteristic of Persian

In the data set we gathered, this pattern of distinctive Raji vocabulary is especially well-represented among verbs.

Concerning phonology: when cognate lexical items are shared among all three varieties (cf. Pattern 1), the Raji words often exhibit shared sound changes that are not found in Persian (see Table 4).

Table 4. Sound changes shared between the two Raji dialects but not Persian

One of the more striking divergences of the Raji phonological inventory from Persian, not reported in Lecoq's 2003 work but seen here, is the presence of the central pharyngealized vowel ạ [a̠ˁ].Footnote 83 This vowel often corresponds to modern Persian posterior ā [ɑ] (itself a reflex of Middle Persian ā [aː]), but as shown with “hand” immediately above, it also appears in contexts analogous to Persian a. The vowels ü [y] and ö [ɵ] are also found in Raji, but not in Persian, as seen in the Raji words šü “husband” and dö “two.”

As mentioned in the discussion of Pattern 1, the JBIL questionnaire is not designed for morphosyntactic analysis. However, even with a very limited selection of morphosyntactic data, two Raji verbal structures show up which differ from Persian. The first is a be-/ba- past marker, evident in the 3sg.m past conjugation of “say” given above; the corresponding 3sg.m present forms are eʋạji (RA) and aʋje (RB). The second is the presence of other preverbal prefixes in Raji, such as the ʋe-/ʋa- prefix (along with allomorphs like ʋạ) seen in the 3sg.m past forms of “sew” above. This prefix is found in both present and past verb forms: 3sg.m present verb forms are ʋadarzi (RA) and ʋạdạrze (RB); in the past forms (given above), it replaces the past marker.

A further difference observed in the course of fieldwork, but not collected as the single reference past and present verb forms for the Raji lists, is the existence in Raji of distinct masculine and feminine 3sg conjugations. This typological difference has been observed elsewhere for related languages.Footnote 84

Pattern 3 (moderate): Persian and each of the Raji dialects are distinct. There are some cases in the data where Persian, Raji of Abuzeydabad, and Raji of Barzok each exhibit a distinctive structure (see Table 5).

Table 5. Words with distinctive structures in Persian and each of the two Raji dialects

As with the other patterns (Patterns 1 and 2), there are cases of full or partial cognacy here (for example, “eye,” “run,” “carry,” “pour,” and possibly “small”), but the historical changes that have applied (or not applied) in each of the words are in many cases dramatically different from one another.

In morphosyntax, Raji of Abuzeydabad exhibits a recurrent ho- prefix, perhaps marking continuative or progressive aspect, with many past and present verb forms (as in “drink” above). Raji of Barzok, for its part, contains a recurrent -š- element in past verb forms only (as in “run,” “hit,” and “grind” above), especially when no explicit object is mentioned in the host utterance. However, the exact function and distribution of each of these elements deserves further investigation as part of an integrated study of the language's grammar.

Pattern 4 (strong): Raji of Abuzeydabad shares features with Persian which Raji of Barzok does not. There is a strong fourth pattern in which features in Raji of Abuzeydabad and Persian are aligned, but Raji of Barzok differs. Given the dominance of Persian over millennia in this area, as elsewhere in Iran, this suggests that Raji of Abuzeydabad is converging with Persian, and with greater intensity than in the dialect of Barzok. Table 6 shows this pattern in the following words:

Table 6. Examples of alignment of Raji of Abuzeydabad with Persian against Raji of Barzok

While most of the examples above suggest borrowing of unrelated Persian lexical items into Raji of Abuzeydabad, it is clear that other items (e.g., “one,” “wolf,” “fox”; possibly “with”) have been replaced by Persian cognates. In still other cases (“mouth,” “back,” “mountain”; possibly “dry”), it is conceivable that a localized lexical or phonological innovation has taken place in Raji of Barzok, but this can only be established through further comparison with other Raji varieties.

Pattern 5 (moderate): Raji of Barzok shares features with Persian which Raji of Abuzeydabad does not. While the alignment of Persian with Raji of Barzok against the dialect of Abuzeydabad occurs in a few items, the small set of examples in the data (Table 7) demonstrates that this pattern is fairly weak:

Table 7. Examples of alignment of Raji of Barzok with Persian against Raji of Abuzeydabad

The apparent alignment of these Barzoki items with Persian is in some cases likely due to Persian influence (“walnut,” “how”), but just as often it appears to be attributable to phonological and lexical innovations in Raji of Abuzeydabad (“knee,” “child,” “good,” “bad,” “short”).

Pattern 6 (moderate): Raji of Abuzeydabad exhibits features which are structurally intermediate between Persian and Raji of Barzok. In the course of data analysis, we unexpectedly encountered a number of cases that exhibit this additional pattern (see Table 8):

Table 8. Examples of features in Raji of Abuzeydabad which are structurally intermediate between Persian and Raji of Barzok

That there should be any such cases is significant, and this strengthens the idea that the Raji—and in particular the dialect of Abuzeydabad—is converging toward Persian in gradient ways, not just through wholesale borrowing.

Notably, we identified very few cases of an equivalent corresponding pattern, where features in Raji of Barzok are structurally intermediate between those of Persian and Raji of Abuzeydabad. One such example is P zabān, RB zeʋun, RA zoyu “tongue.” So not only are there fewer borrowings from Persian into RB, as compared to RA, but there also appears to be less structural hybridization with Persian there too.

Summary of tendencies in linguistic convergence. In our comparative analysis of contact-induced change from Persian (P) in the Raji dialects of Abuzeydabad (RA) and Barzok (RB), we have shown that:

• P, RA, and RB share many features (Pattern 1);

• RA and RB share many features which are not found in P (Pattern 2);

• there are some cases where P, RA, and RB all have different features for a given item (Pattern 3);

• RA often patterns with P, against RB (Pattern 4); but

• RB patterns only infrequently with P again RA (Pattern 5); and,

• unexpectedly, there are a number of RA forms that are transitional between P and RB (Pattern 6).

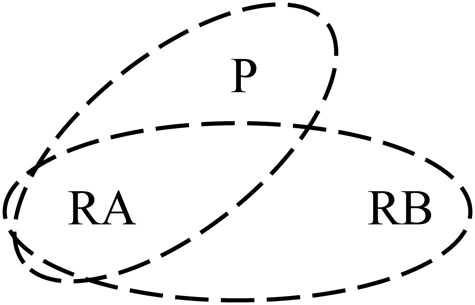

In short, both Raji dialects show effects of contact influence from Persian, but these effects are significantly stronger in the dialect of Abuzeydabad. This asymmetrical configuration is shown in two ways. This first schema (Figure 4) summarizes the patterns of similarity between linguistic features in the three varieties, and the strength of each pattern, to the extent possible within a single diagram.

Figure 4. Structural similarity between features in Persian (P) and the Raji dialects of Abuzeydabad (RA) and Barzok (RB)

In the second diagram (Figure 5), we represent the extent of structural effects of Persian influence in particular.

Figure 5. Intensity of influence and resulting structural convergence with Persian (P) in the Raji dialects of Abuzeydabad (RA) and Barzok (RB)

Since, as explained in the introduction to this paper and reiterated below, fundamental background factors of population and distance from the large Persian-speaking urban centre of Kashan are equivalent, what other factors have led to the dialects’ different degrees of convergence with Persian?

5. Factors related to different patterns of convergence in the two Raji dialects

In the first half of this paper, we have provided a systematic analysis of how lexical items, as well as selected phonological and morphosyntactic features, are aligned in Persian (P), Raji of Abuzeydabad (RA), and Raji of Barzok (RB). As expected for any similar comparison between Persian and other Iranic languages, these patterns include shared inherited structures, influence from Persian on the other varieties, and individual innovations that take place in each of the three varieties. In addition, however, we have shown that RA exhibits a greater degree of structural convergence with P than RB does, including not only direct borrowing of Persian forms into RA, but also a number of RA forms which appear to be intermediate between P and RB.

Here, we seek to understand the geographic and social factors relevant to each of the two dialects—RA and RB—that have contributed to their differing patterns of convergence with Persian. In the following sections, we review geographic and demographic considerations, followed by an examination of pertinent social factors that we have documented: self-identification of Raji speakers as ethnic Persians; the predictable impact of media and schooling; but also interesting, and ambivalent, patterns of mobility. We then turn our attention to the prevalent phenomenon of language shift, which patterns differently from the tendencies of linguistic convergence observed so far.

Geographic and demographic considerations. At first glance, it appears that the Raji language communities of Abuzeydabad and Barzok are found in similar contexts with respect to geographic factors relevant to language contact. The two towns seem to be equivalent in terms of demography: according to the 2016 census, Abuzeydabad has a population of 5,976, and Barzok has 4,588 inhabitants.Footnote 87 As the crow flies, Abuzeydabad is 34 km from the Persian-speaking district capital of Kashan (pop. 304,487); Barzok, at 27 km in a direct line to this city, is slightly closer (see Figure 1 above). In terms of travel by road, the distances are still similar: Abuzeydabad is 39 km away from Kashan, and Barzok is 52 km away.

However, the geographic settings of the two towns are in stark contrast: Abuzeydabad, at 947 m above sea level, is a desert oasis (Figure 6). Barzok is a well-watered farming community at an altitude of 2080 m in the mountains nearby (Figure 7).Footnote 88

Figure 6. View of Abuzeydabad (photo © 2005 Hossein Akrami, http://pic2050.blogfa.com, used with permission)

Figure 7. View of Barzok (photo © 2018 Mahnaz Talebi-Dastenaei)

While the road between Abuzeydabad and Kashan (elevation 954 m) travels straight over a plain, the road from Kashan to Barzok is steep and windy. These very different situations lead to different types of movement between the city of Kashan and each of the towns.

Patterns of mobility. In contrast to the arduous road between Barzok and Kashan, the straight highway between Abuzeydabad and Kashan facilitates travel between the two communities. This ease of movement applies in both directions: people from Abuzeydabad can easily shuttle back and forth to and from Kashan, but there is also a steady stream of Persian-speaking tourists who visit the town each weekend and on holidays. This ensures constant contact between Raji speakers in Abuzeydabad and urban speakers of Persian.Footnote 89 While Barzok is set in a picturesque location, the relative difficulty of travelling there means that it receives fewer visitors.

Ironically, though, the more isolated situation of Barzok has led to intense contact of another type between members of this community and the population of Kashan. Due to its location at a high altitude in the mountains, Barzok experiences severe winter weather, with temperatures lower than -10°C and regular snowfall over three months, with accumulations of up to one metre recorded. Because of the weather, until the recent past, most inhabitants of Barzok spent several months in Kashan each year, and those with school-age children stayed there for the whole school year, returning to Barzok only for the summer. Although improvements to infrastructure now enable some of Barzok's inhabitants to brave the winter in their hometown, some still migrate to the city nearby. These people retain their tight social bonds with other people from Barzok when they are in Kashan, but are nonetheless constantly exposed to Persian language in their daily interactions with the rest of the city's populace.

In the past, before high schools were built in Barzok and Abuzeydabad in the 1970s, students from both towns were obliged to move to Kashan to complete their secondary education. This relocation was a further factor in increased mobility and contact for each of the Raji language communities with Persian speakers.

Other major factors. Other key factors in contact-induced change in Raji, affecting both Raji-speaking populations equally, are common to language communities in many parts of Iran. First, language identity is conducive to language change. Raji communities view themselves as ethnically Persian, and therefore speakers of Persian, even though Raji is not closely related to Persian (as outlined in the classification presented in the Introduction). This self-identification with a wider Persian language community promotes a positive attitude toward the spoken and written Persian norms, and reinforces speakers’ perception of their own vernacular as deviations from this norm. The diffusion of mass media has an additional pervasive impact on the linguistic ecology. It is now exponentially increased with the advent of satellite television (there are now 30 national channels available across Iran) and internet, but almost exclusively in Persian language.Footnote 90 Further, as is the case throughout Iran, Persian is viewed as a language of economic opportunity. Finally, the enforcement of Persian as the language of education has affected all children in all Raji villages, and initiated a process of language shift as a result of the steady universalization of education in Iran over the course of the 20th century. The profound significance of these factors in the convergence of both Raji dialects toward Persian would be difficult to underestimate.

Linguistic convergence vs. language shift. Up to this point, we have focussed on the linguistic convergence of two Raji dialects, those of Abuzeydabad and Barzok, with Persian. However, a discussion of language shift is an additional key element in an understanding of the language situation. Although Raji of Abuzeydabad has undergone greater structural influence from Persian, community-level shift to use of Persian across domains, and the emergence and expansion of Persian as a mother tongue in the community, is more advanced in Barzok than in Abuzeydabad. Talebi-Dastenaei notes that whereas most people under forty-five years of age in Barzok now speak Persian as a first language, Raji is still the dominant mother tongue among adults in Abuzeydabad.Footnote 91 How can this situation be reconciled with the increased incidence of contact-induced change in the linguistic structures of Raji of Abuzeydabad, as compared to Raji of Barzok?

5. Discussion and conclusions: Social networks and outcomes of contact

Many inherited structures common to Persian (P), Raji of Abuzeydabad (RA), and Raji of Barzok (RB) (Pattern 1) have a shared basis. However, as introduced at the beginning of this paper, languages structures may undergo changes due to factors within the language and language community, and these changes often come about as a result of isolation. Each of the three varieties—P, RA, and RB—exhibits apparent innovations which are not found in the other varieties (Pattern 3, but also Patterns 4 and 5 above), and this confirms the operation of internal changes, along with a certain degree of isolation between the language communities.

More significant to the situation under investigation, however, is the operation of structural changes as a result of language contact. There are similar outcomes, in many cases, of Persian influence on RA and RB (Pattern 2). This pattern confirms a configuration of the overall language situation in Iran which is widely recognized. The large Persian-speaking urban centre of Kashan is at the centre of social networks in the region, and Persian is a more dominant and prestigious language, so that the people of Abuzeydabad and Barzok naturally accommodate themselves linguistically in interactions with people from this city.Footnote 92 Migrants from the two towns who live in Kashan and travel regularly back their own villages bring with them linguistic souvenirs—lexical, phonological and grammatical—that are in turn adopted by other individuals in the towns, a critical stage in the community-wide absorption of contact-induced change. In the course of time, these individuals introduce the new linguistic features through their own social network. Success in diffusion of the new features to others in their network, and subsequently to other networks (Figure 8), depends on the position of the individual member within a group, the type of their contacts in the network, the intensity of the contacts, prestige, and often also age and gender.Footnote 93

Figure 8. “Contagious diffusion” of structural features through social networksFootnote 94

The process of “contagious diffusion” is strongest among young people,Footnote 95 such as the students who move to Kashan to complete their schooling but still regularly travel back to their hometowns. The progression of linguistic convergence as a whole is framed by language identity: since Raji speakers identify themselves as ethnically Persian,Footnote 96 they are not generally antagonistic to Persian language structures, and this strengthens the process of diffusion.Footnote 97 Yet even between the two Raji communities, language attitudes vary: from our observations, people of all ages in Abuzeydabad are receptive to diffusion of Persian structures into Raji, whereas in Barzok, older speakers are less receptive.Footnote 98

This brings us to the central question of the paper, namely: why is linguistic convergence toward Persian stronger in Raji of Abuzeydabad than in Raji of Barzok, as evidenced by Patterns 4 and 6 above? While many of the contextual factors are equivalent, and patterns of diffusion are similar, easier access and the resulting frequent travel between Kashan and Abuzeydabad appears to be a main difference. Interestingly, the seasonal habitation of people from Barzok in the city of Kashan, which brings about intense language contact for part of the year, does not seem to outweigh the intensity of structural convergence toward Persian which is evident in the dialect of Abuzeydabad.

However, there is a complementary question that needs to be addressed, and this one points in the opposite direction: if geographic and social factors are more favourable to adoption of Persian structures in Raji of Abuzeydabad, why is shift toward Persian (as observed at the end of section 3 above) more advanced in the community of Barzok? When the people of Barzok spend their winters in Kashan, they constitute a tightly-knit community. Among the Barzoki speakers of Raji who migrate each year to the city, there may be greater awareness of social distinctness than among the individuals from Abuzeydabad who travel back and forth more regularly; a resulting sense of communal solidarity among the people from Barzok may slow the transmission of Persian structures into their own language, when they do speak it. However, due to the length and intensity of their contact with Persian during their seasonal relocation each year, Raji's very future as the language of this community has been put into question. Rather than a more gradual convergence with Persian, as seen in the dialect of Abuzeydabad, there appears to be an abrupt capitulation in the language practices of the people of Barzok, once Persian has made itself at home in all domains of their lives.