Introduction

Family involvement (FI) with care homes following placement of a relative living with dementia is vital in our current care climate. FI forms part of the recommended person-centred care (PCC) approach (van der Steen et al., Reference van der Steen, Radbruch, Hertogh, de Boer, Hughes, Larkin, Francke, Junger, Gove, Firth, Koopmans and Volicer2014; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2018) and has been linked with positive outcomes for residents, families and staff (Maas et al., Reference Maas, Reed, Park, Specht, Schutte, Kelley, Swanson, Trip-Reimer and Buckwalter2004; Castro-Monteiro et al., Reference Castro-Monteiro, Alhayek-Ai, Diaz-Redondo, Ayala, Rodriguez-Blazquez, Rojo-Perez, Martinez-Martin and Forjaz2016). In the United Kingdom (UK) and following the Winterbourne View (Department of Health, 2012) and Francis (The Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, 2013) reports, FI is central to ensuring increased transparency and partnership between care provider and client (Department of Health, 2013; van der Steen et al., Reference van der Steen, Radbruch, Hertogh, de Boer, Hughes, Larkin, Francke, Junger, Gove, Firth, Koopmans and Volicer2014; Care Quality Commission (CQC), 2015) alongside national care quality assessment.

Approximately one-third to one-half of people living with dementia in high-income countries, and approximately 6 per cent of those in low- and middle-income countries are cared for in long-term care facilities (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Bryce, Albanese, Wimo, Ribeiro and Ferri2013). With 46.8 million people worldwide living with dementia in 2015 and this number predicted to double every 20 years for the foreseeable future, it is probable that residents living with dementia will remain the majority service user group in care homes (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2015).

This prediction is additionally credible as cultural and social norms begin to change in families and societies, such as China and East Asia where, until recently, the prevalent attitude has been to care for relatives at home (Yamashita et al., Reference Yamashita, Soma, Chan and Izuhara2013; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Clarke and Rhynas2020). The rise of increasingly individualised rather than collective approaches to family working and living arrangements has meant intergenerational families are no longer universally living together. Despite lack of suitable and available institutions, stigma and other barriers to engagement (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Clarke and Rhynas2020), demand for care homes is likely to increase from families, with diverse cultures, who have not previously sought support for relatives living with dementia.

Care providers may increasingly turn to and benefit from families’ assistance with facilitation of a high quality of care for residents (Port et al., Reference Port, Hebel, Gruber-Baldini, Baumgarten, Burton, Zimmerman and Magaziner2003). While not every care home resident living with dementia has family or has family available and willing to engage (van der Steen et al., Reference van der Steen, Arcand, Toscani, de Graas, Finetti, Beaulieu, Brazil, Nakanishi, Nakashima, Knol and Hertogh2012), understanding the nature and impact of FI with care homes may provide insights into improved care processes that benefit all residents.

Theory, person and family-centred care

FI has been described as a multi-dimensional construct that entails visiting, socio-emotional care, advocacy and the provision of personal care (Gaugler, Reference Gaugler2005; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Chappell and Gish2007). Theoretical frameworks for FI have predominantly focused on person–environment fit and interaction (Powell et al., Reference Powell Lawton, Nahemow and Teaff1975; Kahana et al., Reference Kahana, Lovegreen, Kahana and Kahana2003), role theory (Biddle, Reference Biddle1986), family systems theory (Minuchin, Reference Minuchin1974) and stress theory (Pearlin et al., Reference Pearlin, Mullan, Semple and Skaff1990). Theories posit that person–environment fit, interaction and patterns of communication alter over time, for residents living with dementia, family and staff. Environmental interventions are tried in the pursuit of stress reduction and to meet the evolving needs of the resident as dementia progresses. Families are challenged to adapt their intergenerationally established and stable patterns for communication and interrelation, to cope with a relative's long-term care placement. Levels of stress and burden change as social positions and care-giver roles and role nature (the number of roles, intensity, ambiguity, expectations, skill demand, conflict, norms and behaviours) change. While adapting, families are challenged with ensuring care homes accommodate their cultural and heritage-related differences in family participation. A new area of importance, further research into cultural drivers of FI is needed (McCreedy et al., Reference McCreedy, Loomer, Palmer, Mitchell, Volandes and Mor2018).

FI and PCC are accepted standards in dementia service provision (Brooker, Reference Brooker2004) and their emphasis appears to somewhat lessen the impact of the challenges for families (especially as they encompass much more than medical concerns). However, demonstrating evidence for psycho-social interventions such as PCC is far from straightforward (Fazio et al., Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018) and it is similarly difficult for FI. To underline this point, few common definitions of PCC exist (Kitson et al., Reference Kitson, Marshall, Bassett and Zeitz2013); for examples, see Brooker (Reference Brooker2004) and Vernooij-Dassen and Moniz-Cook (Reference Vernooij-Dassen and Moniz-Cook2016). There are common themes in the application of PCC, though emphasis has varied (Kitson et al., Reference Kitson, Marshall, Bassett and Zeitz2013) and specific person-centred activities can be infrequent (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Marston, Barber, Livingston, Rapaport, Higgs and Livingston2018). PCC themes have intermittently involved family carers (Kitson et al., Reference Kitson, Marshall, Bassett and Zeitz2013). Recently, after a review of the literature describing PCC for people living with dementia, Fazio et al. (Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018) recommended six practices for PCC including Create and maintain a supportive community for individuals, families and staff.

In an extension of PCC, family-centred care (FCC) has grown in attention and has been found effective in the dementia field (one example is the study by Maio et al., Reference Maio, Botsford and Iliffe2016). Again, debate remains about the definition of FCC (Shields, Reference Shields2015; Giosa et al., Reference Giosa, Holyoke and Stolee2019; Hao and Ruggiano, Reference Hao and Ruggiano2020) and its merits are not without controversy (Shields, Reference Shields2010). However, a FCC approach is more likely to mitigate family challenges, all while maintaining best practice of care for relatives living with dementia.

Originating in paediatrics, FCC is characterised by several principles, including (a) respect and incorporation of family perspectives, choices and cultural preferences; (b) helpful, affirming sharing of timely, complete and unbiased information with families; (c) families to be encouraged and supported to participate in care and decision making; (d) collaboration with families in policy and programme development, implementation and evaluation, and care delivery (Institute of Patient and Family Centred Care (IPFCC), 2020).

After a review of older adults’ care preferences, Etkind et al. (Reference Etkind, Bone, Lovell, Higginson and Murtagh2018) proposed older people with illnesses and their families should be considered together as a care unit. The NICE (2018) definition of PCC reflects this. While it does not outline the FCC components above, it acknowledges the human value of family in its first principle and makes an additional reference to the importance of accounting for family carer needs. FCC and related research is necessary while demand for care homes rises, staff increase their reliance on families to fill gaps in service provision and optimum care standards are sought. With PCC and FCC principles in mind, what does the existing research and literature tell us about dementia-specific FI with care homes?

Existing literature reviews

A major review of approximately 100 studies pertaining to FI in residential long-term care was previously published (Gaugler, Reference Gaugler2005). It focused primarily on US-based research and reference was made to eight studies involving residents living with dementia. Findings highlighted that family members continued to participate in their relatives’ lives (though the frequency and duration of visits fluctuated) and types of involvement beyond activities of daily living (ADL) included supervision and monitoring of quality of care. Factors found to influence visits and involvement included stronger family–resident relationships, social resources, resident length of stay and frequency of pre-placement behavioural difficulties. The review supported the link between family visits and benefits for residents such as reduced infections and hospitalisations. With the synthesis being over 14 years old, it is not known if there have been any changes in this arena.

Petriwskyj et al. (Reference Petriwskyj, Gibson, Parker, Banks, Andrews and Robinson2014) conducted a review of 26 studies published between 1990 and 2013. This review offers an insight into the advocacy role of family members and factors influencing participation. However, it was limited to decision-making aspects of FI and primarily focused on choices relating to medical issues.

A meta-ethnographic review by Graneheim et al. (Reference Graneheim, Johansson and Lindgren2014) involving ten studies found family care-givers described their experiences of relinquishing the care of a person living with dementia as a process. Authors proposed family adaptation to relative placement in care homes can be facilitated when families are recognised as care partners. However, the review emphasis was on the emotional strain family care-givers face through the transition.

A review by Law et al. (Reference Law, Patterson and Muers2017) focused on family satisfaction with staff and yielded 14 studies. They highlighted families’ preference for shared responsibility for care, ongoing relationships with staff and effective staff communication with family. Types of involvement and factors influencing FI with care homes were not specifically examined.

Current literature review

Our literature review developed Gaugler's (Reference Gaugler2005) synthesis of FI with care homes by providing an update on global developments over the last 14 years with specific reference to families of residents living with dementia.

Literature review questions

The following research questions were addressed:

(1) What types of involvement do families have with care homes following placement of a person living with dementia?

(2) Which factors influence FI with care homes following placement of a person living with dementia?

In addition to the multiple points raised in the introduction and theory section, asking these ‘back to basics’ questions was important for multiple reasons. Existing reviews are outdated or have focused on medical choices, role adjustment or satisfaction with staff. Therefore, this review provides a timely update for the existing evidence base; developments are highlighted, previously made recommendations that have yet to be pursued are discovered and the current literature is checked for how well it represents the global concern.

To our knowledge, there is no comprehensive reference list and discussion of these topics focused on dementia and care homes. The authors’ review fills a gap and sets a baseline for future dementia-specific reviews. It also prevents the literature base from assuming or implying FI with care homes is the same regardless of whether dementia is involved or not.

Our exploration aims to shape the foundations of and inform future developments in PCC and FCC care home approaches, policies and programmes; it will go beyond medical decisions. Family-centred research is crucial because it embodies the first principle of FCC; dignity and respect for older adult and family wishes, both of whom prefer families are involved in care (Petriwksyj et al., Reference Petriwskyj, Gibson, Parker, Banks, Andrews and Robinson2014; Etkind et al., Reference Etkind, Bone, Lovell, Higginson and Murtagh2018). This review will enable researchers and care homes to understand what the family actually does, and give insight into what influences this activity and consider these factors when creating and delivering standardised versus customised residential dementia care services.

Finally, this review is important because while its research questions stand alone, it also compliments another dementia-focused review by Hayward, J.K., Gould, C., Palluotto, E., Kitson, E.C., Fisher, E.R. and Spector, A. (submitted) spanning January 2005 to April 2021. Measures of FI and interventions designed to foster FI with care homes were explored. Studies reporting the impact of FI on resident behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) were also investigated. The specific research questions asked were: (a) which interventions concerning FI have been evaluated? and (b) does FI within care homes have a positive effect on resident quality of life and BPSD symptoms of dementia? While the research questions in both reviews are distinct, together they provide a comprehensive picture of the available FI evidence base.

Method

This literature review is based on the University of York – Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2009) guidelines on conducting systematic literature reviews in health care. The full inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows.

Inclusion criteria

• Randomised controlled trial designs, quasi-experimental designs, interrupted time-series designs with the family member or family member and their relative as own comparison and qualitative studies.

• Families with a relative living with dementia residing in a residential care home or nursing home.

• Studies where N ⩾ 10.

• Published in English in peer-reviewed journals between 2005 and 2018.

• Training or interventions for families (or families and residents) that pertained to FI or partnership with long-term care providers and related resident psycho-social outcomes.

Exclusion criteria

• Studies, training or interventions solely set in home care, assisted community living or inpatient settings.

• Training or interventions for staff and/or residents that did not involve families.

• Family interventions focused solely on physical, medical or non-psychological outcomes, e.g. decisions about psychotropic medication.

• Studies focused exclusively on care-giver burden, stress or wellbeing.

• End-of-life or advanced care planning studies where FI was not of primary interest.

Search strategy

In January 2016 databases PsycINFO, MEDLINE and CINAHL Plus were searched for papers published between 2005 and 2015. This search was extended in May 2019 to include 2016–2018. Key terms were entered into Keyword, Subject heading and Ovid .mp searches in order to find studies pertaining to FI (‘family’, ‘families’, ‘informal caregiver’, ‘involvement’, ‘engagement’, ‘participation’, ‘role/roles’, ‘interaction’, ‘visit/visiting’) within a care home setting (‘care home’, ‘residential care’, ‘residential aged care’, ‘nursing home’, ‘skilled nursing facility/facilities’, ‘institutionalisation’, ‘long-term care’) for relatives with a diagnosis of dementia (‘dementia’, ‘Alzheimer's’, ‘Alzheimer's disease’). Key phrases were also used to ensure a broad search (‘working with families’ and ‘family–staff relationships’).

Three authors reviewed the papers ensuing from the search by title, abstract and full paper according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A snowball sampling strategy was used as reference lists from systematic reviews and each selected paper was examined to identify additional studies.

Quality rating

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) – Version 2011 developed by Pluye et al. (Reference Pluye, Robert, Cargo, Bartlett, O'Cathain, Griffiths, Boardman, Gagnon and Rousseau2011) was chosen to assess the quality of studies as it enables the rating of studies with various methodologies. Permission to use the MMAT was obtained from the authors. Four researchers applied the tool and sought consensus when any differences arose.

Ratings of quality were based on a 21-criteria checklist involving two screening questions for all studies and five sections; qualitative (four criteria), quantitative (randomised, non-randomised and descriptive, all with four criteria each) and mixed methods (three criteria). The sections and sub-sets of criteria were applied according to the type of study being reviewed. Responses to rating questions included ‘Yes’, ‘No’ and ‘Can't tell’.

Papers received a score denoted by descriptors *, **, *** and ****. For qualitative and quantitative studies, this score is the number of criteria met divided by four with scores varying from 25 per cent (*) with one criterion met to 100 per cent (****) with all criteria met. For mixed-methods studies, overall quality is the lowest score of the study components. Criteria included quality of data sources, consideration of researcher influence and sample recruitment bias, as well as data outcome completion and dropout rates.

Classification and analysis

The selected studies were classified according to the research questions posed and divided into two tables by methodology. A synopsis and appraisal result for all included papers are provided. Results were analysed and reported in relation to PCC and FCC frameworks. A convergent approach (Creswell et al., Reference Creswell, Klassen, Plano Clark and Smith2011) was predominantly employed for reporting the review findings in relation to each research question.

Results

Included studies

A total of 475 papers were identified from the database searches, 311 of which were excluded based on the above exclusion criteria and a review of titles, as they were deemed unrelated to the review topic. Following an abstract review, a further 90 papers were excluded: three were deemed unrelated to the review topic, 16 were not specific to FI, 18 related to non-care home settings, three related to scale development, 12 focused on care-giver grief or burden, ten pertained to biomedical, end-of-life and advanced care planning without emphasis on FI, 18 were reviews, editorial or protocols only, and ten involved samples of less than ten.

The paper identification and eligibility process is depicted in Figure 1 and shows that following a full-text paper review (N = 74), a further 41 papers were excluded. Of the 35 additional papers identified through hand and reference list searches, two-thirds were excluded (N = 22). Thirty-three papers remained for inclusion. Research was primarily conducted in United States of America (USA; N = 10), Canada (N = 5) and Australia (N = 5). Cross-country studies included Italy and the Netherlands (N = 1). Sweden (N = 3), Norway (N = 3), the UK (N = 2) and a paper from each of Belgium, Japan, Israel and Taiwan were found. The papers reported studies with quantitative or mixed-methods (N = 16) and qualitative designs (N = 17).

Figure 1. Flowchart of literature identification and eligibility.

Note: ADL: activities of daily living.

Two papers reported results from the same study (Bramble et al., Reference Bramble, Moyle and McAllister2009, 2011). Data from a study were investigated in three different ways and reported separately (Dobbs et al., Reference Dobbs, Munn, Zimmerman, Boustani, Williams, Sloane and Reed2005; Port et al., Reference Port, Zimmerman, Williams, Dobbs, Preisser and Williams2005; Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Sloane, Williams, Reed, Preisser, Eckert, Boustani and Dobbs2005). Therefore, 33 papers representing 30 studies drawn from 33 datasets were included in this review. The included papers are classified in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Papers reporting studies involving family involvement (FI) types and/or influences with a quantitative or mixed-method design

Notes: ACP: advanced care planning. ADL: activities of daily living. AFC: Attitudes Towards Family Checklist. BANS-S: Bedford Alzheimer's Nursing Severity subscale. BPSD: behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating. CFS: Cognitive Function Scale. CMAI: Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory. CPS: Cognitive Performance Scale. CRCT: clustered randomised controlled trial. CSI: caregiver stress inventory. DBD: Dementia Behaviour Disturbance scale. DCM: Dementia Care Mapping. DEMQOL: Dementia Quality of Life Measure. EOL: end of life. EOLD-SM: End of Life in Dementia Scale - Symptom Management. FIC: Family Involvement in Care. FICS-FII: Those For Whom Family Involvement Is Important. FICS-T: Total Family Involvement Congruence Score. FKOD: Family Knowledge of Dementia test. FPCR: family perceptions of care-giving role. FPCT: Family Perceptions of Care Tool. FPPFC: Physician-Family Care Giver Communication. HDS-R: Hasegawa Dementia Scale-Revised. IADL: instrumental activities of daily living. I/ADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale. MDS-ADL: Minimum Data Set–Activities of Daily Living Scale. MDS-COGS: Minimum Data Set Cognition Scale. MMAT: Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. MMSE: Mini-mental State Examination. Murphy: Murphy et al., 2000 Involvement Scale. NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory. OPTION: Observing Patient Involvement. PAS-AD: Patient Activity Scale–Alzheimer's Disease. QoC: quality of communication. QOL in AD-activity: Quality of Life in Alzheimer's Disease Activity. QUALID: Quality of Life in Late-stage Dementia. UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America. RCT: randomised controlled trial. RQ: research question. SKOD: staff knowledge of dementia test. SPCR: staff perceptions of care-giving role. SWC-EOLD: Satisfaction with Care at the End-of-Life in Dementia Scale. ZBI: Zarit Burden Interview.

Table 2. Papers reporting studies involving family involvement (FI) types and or influences with a qualitative design

Notes: MMAT: Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. PCC: person-centred care. RQ: research question. SDM: Shared Decision Making. UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America.

Study design and quality

Quality ratings ranged from * to **** (see Table 3), indicating a wide variation in study quality. Despite this, most studies scored *** or above and showed methodological strengths in setting out study objectives, including multiple sites in their samples, applying site randomisation, describing analyses, use of verification procedures and drawing conclusions in line with results. The remaining studies rated in the review were of low to medium quality, receiving ratings between * and **. Generally, studies had appropriate study designs for the questions posed and conclusions that were supported by their results. However, some studies did not appear to consider power, had sample sizes that were too small for analyses conducted and had high attrition rates, while the quality of other studies were reduced by incomplete reporting of data collection or results.

Table 3. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) scores for included studies

Research questions

Results addressing the first two research questions are reported here.

Research question 1: What type of involvement do families have with care homes following placement of people living with dementia?

FI is complex, multi-dimensional and potentially unique for each family. For example, families’ reasons for moving their relatives living with dementia to a care home mentioned in the papers included aggressive behaviour, care-giver burden, need for help with end-of-life care and deteriorating relationships. Twenty-eight out of the 33 papers informed the varied and related types of FI shown in Table 4. Of the nine cross-sectional analyses, five correlational longitudinal analyses, one descriptive analysis and 13 qualitative studies, three achieved MMAT scores of ** or below. Findings remain included as other studies identified similar types of FI.

Table 4. Types of family involvement after placement of a relative living with dementia

Notes: Italics refer to a ‘new’ type or sub-type of involvement, i.e. a type that was not distinguished (‘known’) in the paper by Gaugler (Reference Gaugler2005). Apart from ‘new’ types of family involvement, sub-types within personal, instrumental, preservative and psycho-social support are well known and have not been displayed to save space. References to Bramble refer to Bramble et al. (Reference Bramble, Moyle and McAllister2009) and Helgesen1 refers to Helgesen et al. (Reference Helgesen, Athlin and Larsson2015) (authors involved in multiple papers in this review).

One study found that families perceived there to be fewer opportunities for participation in the very types of involvement they deemed to be most important: ensuring a well-cared for relative, active development of trust in staff, inclusion in decision making and being informed about care plan changes (Reid and Chappell, Reference Reid and Chappell2017). Similarly, in a large sample, families reported a difference between actual and wished-for involvement (Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Athlin and Larsson2015).

While families acted as advocates and spokespeople for relatives after placement (Port et al., Reference Port, Zimmerman, Williams, Dobbs, Preisser and Williams2005; Bramble et al., Reference Bramble, Moyle and McAllister2009; Legault and Ducharme, Reference Legault and Ducharme2009; Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Larsson and Athlin2012, 2015), one study found families rarely participated in decision making regarding relatives’ everyday care or health care (Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Athlin and Larsson2015). Four studies found types of FI included seeking connection and collaboration with staff, preserving both the continuity of family–resident relationship and the resident's sense of self (Strang et al., Reference Strang, Koop, Dupuis-Blanchard, Nordstrom and Thompson2006; Bramble et al., Reference Bramble, Moyle and McAllister2009; Edvardsson et al., Reference Edvardsson, Fetherstonhaugh and Nay2010; Lethin et al., Reference Lethin, Hallberg, Karlsson and Janlov2016).

Seven studies considered types of involvement alongside satisfaction and confidence in care and found contrasting results (Levy-Storms and Miller-Martinez, Reference Levy-Storms and Miller-Martinez2005; Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006; Grabowski and Mitchell, Reference Grabowski and Mitchell2009; Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Larsson and Athlin2012; Reinhardt et al., Reference Reinhardt, Boerner and Downes2015; Lethin et al., Reference Lethin, Hallberg, Karlsson and Janlov2016; Toles et al., Reference Toles, Song, Lin and Hanson2018). While satisfaction with care was highest where families had minimal or no involvement with care homes (Grabowski and Mitchell, Reference Grabowski and Mitchell2009), for other families, the more they were involved in discussions with staff, the greater their satisfaction with care (Reinhardt et al., Reference Reinhardt, Boerner and Downes2015) and sense of security (Lethin et al., Reference Lethin, Hallberg, Karlsson and Janlov2016). FI in the provision of personal and instrumental care prior to placement was related to lower levels of satisfaction with care, provided by the care home at admission, and this did not change over time (Levy-Storms and Miller-Martinez, Reference Levy-Storms and Miller-Martinez2005).

Visitation, frequency and level of FI

Twelve studies explored frequency of involvement with visits as a core domain (Dobbs et al., Reference Dobbs, Munn, Zimmerman, Boustani, Williams, Sloane and Reed2005; Port et al., Reference Port, Zimmerman, Williams, Dobbs, Preisser and Williams2005; Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Sloane, Williams, Reed, Preisser, Eckert, Boustani and Dobbs2005; Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006; Minematsu, Reference Minematsu2006; Grabowski and Mitchell, Reference Grabowski and Mitchell2009; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Zimmerman, Reed, Sloane, Beeber, Washington, Cagle and Gwyther2014; Hegelsen et al., Reference Helgesen, Athlin and Larsson2015; Reinhardt et al., Reference Reinhardt, Boerner and Downes2015; Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Barber, Marston, Rapaport, Livingston, Cousins, Robertson, La Frenais F and Cooper2017; Seiger Cronfalk et al., Reference Seiger Cronfalk, Ternestedt and Norberg2017; Forsund and Ytrehus, Reference Forsund and Ytrehus2018). An additional study captured the level of FI in care using a multifactorial scale that included visits (Boogaard et al., Reference Boogaard, Werner, Zisberg and Van der Steen2017).

Most papers reported or demonstrated that the majority of families remain involved with relatives following placement. In the Livingston et al. (Reference Livingston, Barber, Marston, Rapaport, Livingston, Cousins, Robertson, La Frenais F and Cooper2017) study with a large sample (N > 1,000), the median number of visits to residents by a main family carer was found to be six per month. A correlational study (N = 90) noted in their sample description that 47 per cent of families visited relatives at least once per week (Reinhardt et al., Reference Reinhardt, Boerner and Downes2015). Two cross-sectional studies (Dobbs et al., Reference Dobbs, Munn, Zimmerman, Boustani, Williams, Sloane and Reed2005; Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Athlin and Larsson2015) with larger samples (N = 400; N = 233) found the percentages of visiting families were higher: 70 and 84.1 per cent, respectively.

Four correlational studies reported that some families spend seven or more hours per week or over ten visits per month with residents (Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Sloane, Williams, Reed, Preisser, Eckert, Boustani and Dobbs2005; Minematsu, Reference Minematsu2006; Grabowski and Mitchell, Reference Grabowski and Mitchell2009; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Zimmerman, Reed, Sloane, Beeber, Washington, Cagle and Gwyther2014). Similarly, participant characteristics described in two qualitative studies (Seiger Cronfalk et al., Reference Seiger Cronfalk, Ternestedt and Norberg2017; Forsund and Ytrehus, Reference Forsund and Ytrehus2018) noted a minimum of weekly visits and an average number of visits as just over three per week (range of one to seven), respectively.

When non-visit-based FI with care homes is considered, overall FI may be higher. A quantitative study found that 12 months after resident placement, 23 per cent of families had more contact with their relative and the average weekly number of family visits had increased to just over two and a half times per week (Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006). One study compared visits by type of residential facility and found there to be no difference in frequency of visitation (Port et al., Reference Port, Zimmerman, Williams, Dobbs, Preisser and Williams2005).

Boogaard et al. (Reference Boogaard, Werner, Zisberg and Van der Steen2017) explored the level of FI in care (N = 214) across eight factors including visits. They found an average score of 21 out of a possible 40, however, a positive association between FI and overall trust in staff was not sustained once analyses accounted for clustering in nursing homes. Another study of over 18,000 long-stay residents living with dementia revealed that only 16 per cent had a family member or representative involved in at least one planning assessment over the course of one year. Over half of the residents with severe cognitive impairment had no representation in that same period (McCreedy et al., Reference McCreedy, Loomer, Palmer, Mitchell, Volandes and Mor2018).

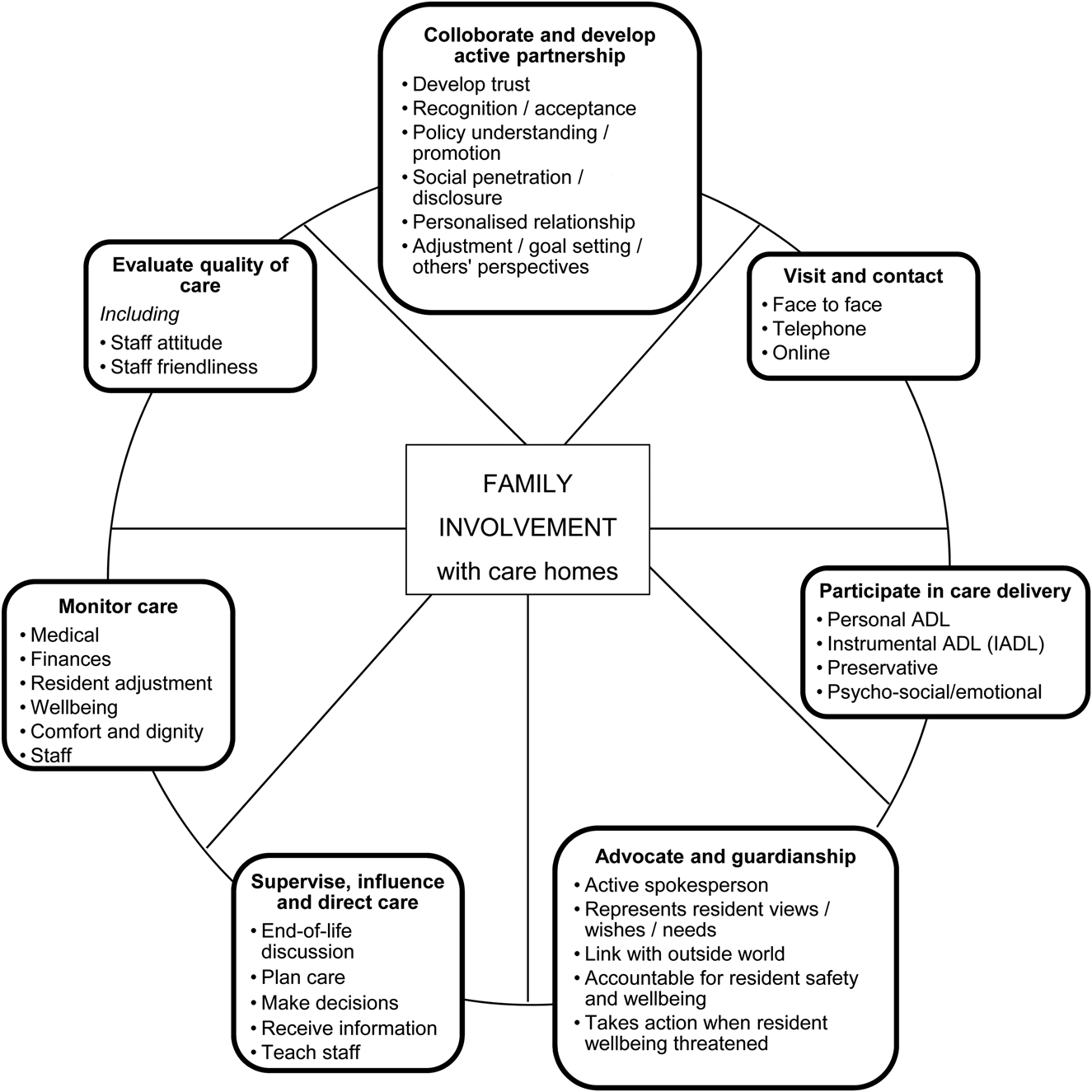

Themes and country representation

During analysis of the included papers, types of FI were grouped for similarity and relatedness. Figure 2 shows seven connected yet distinct themes that stood out amongst the groups: Visit and contact; Participate in care delivery (core needs); Advocate and guardianship; Supervise, influence and direct care; Monitor care; Evaluate quality of care; and Collaborate and develop active partnership . FI themes indicated separate parts of a family- and resident-centred care process, that takes place from the time of a resident's placement to the end of their life. There appeared to be a sequence to some of the themes, for example, Visit–Advocate–Supervise–Monitor–Evaluate. However, the process is more accurately non-linear; themes of FI types are completed in parallel and in an iterative manner.

Figure 2. Non-linear process and related themes in types of family involvement following placement of a relative living with dementia in a care home.

Country differences across themes of FI were compared and are displayed in Table 5. Papers based in Australia, Canada, Sweden and the USA highlighted six or more of all seven themes, while papers from Israel, Italy, Japan and the Netherlands highlighted one (and a different) theme only. The themes with 50 per cent or more of the possible country representation included Visit and contact, Participate in care delivery (core needs), Supervise, influence and direct care and Collaborate and develop active partnership.

Table 5. Themes of family involvement (FI) activities by country and following placement of a relative living with dementia in a care home

Notes: UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America.

Person- and family-centred care

Table 6 shows the proposed assignment of identified FI type to PCC and FCC core principles and concepts; NICE (2018) and IPFCC definitions were employed. Overall, FI types appeared to fit well with PCC and FCC. The majority of FI types matched well to PCC Carer, a statement that refers to the importance of taking account of the needs of carers including family. However, this result was expected. For consistency, authors treated the statement similarly to the distinguished PCC principles and assigned FI types on this basis. This principle proved to be a catch all as many FI types were assigned to it. Likewise, FI activity of collaborate and actively develop family-centred partnerships was not easily assigned to PCC principles, however, it was explicitly addressed in FCC concepts.

Table 6. Types of family involvement in care homes after placement of a relative living with dementia assigned to person-centred care (PCC) and family-centred care (FCC) principles

Notes: 1. PCC principles in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2018) guideline. 2. FCC concepts by the Institute for Patient and Family Centred Care (available at https://www.ipfcc.org/about/pfcc.html, November 2020). 3. Refers to family and friends or paid care workers. 4. Assumes family involvement type encompassed by NICE PCC statement (not a principle) of the importance of taking account of the needs of carers including family.

Of 33 identified types of FI, over 30 per cent matched to the PCC Human value principle. Individuality and Person's perspective attracted under 20 per cent of the possible FI types. Most were assigned to FCC concepts of Participation (64%) and Dignity and respect (39%). In contrast, Information sharing attracted only 5 per cent of possible types of FI.

Research question 2: Which factors influence FI with care homes?

Factors that influence FI are multiple, varied and interwoven across the agents involved; the care home, its staff, the resident and the family (see Table 7). Influences do not occur in isolation. They contribute to the dynamic nature of FI and the unique inter-family and intra-family preferences of and about involvement. Twenty-five of the 33 papers in this review considered factors that influence involvement and a slight majority highlighted at least one factor that either aided involvement or resulted in increased contact or visits. Of the 15 qualitative and ten quantitative studies, one study achieved a MMAT score of * so was excluded from these results. In another study with a score of ** a restricted set of findings are reported here as the results section of the paper appeared incomplete; when additional results (without supporting participant quotes) were reported in the discussion these were excluded from consideration in our review.

Table 7. Agents and factors that influence family involvement (FI) with care homes following placement of a relative with dementia

Notes: 1. Contradictory or competing findings. 2. Helgesen et al. (Reference Helgesen, Athlin and Larsson2015). 3. Bramble et al. (Reference Bramble, Moyle and Shum2011).

Alongside family evaluation of care, the important factors influencing FI found across nine studies were: family trust in staff, family desire for integration into the care team and their wish for development of close, personal, family–staff relationships (Caron et al., Reference Caron, Griffith and Arcand2005; Port et al., Reference Port, Zimmerman, Williams, Dobbs, Preisser and Williams2005; Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Shyu, Lin and Yang2008; Legault and Ducharme, Reference Legault and Ducharme2009; Majerovitz et al., Reference Majerovitz, Mollott and Rudder2009; Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Larsson and Athlin2012; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ruzin, Graneheim and Lindgren2014; Lethin et al., Reference Lethin, Hallberg, Karlsson and Janlov2016; Reid and Chappell, Reference Reid and Chappell2017).

Trust facilitated contact although it both enabled and excused family participation in decision making (Caron et al., Reference Caron, Griffith and Arcand2005; Boogaard et al., Reference Boogaard, Werner, Zisberg and Van der Steen2017; Reid and Chappell, Reference Reid and Chappell2017). A lack of trust and a care evaluation of ‘poor’ were linked with increased supervision and advocacy (Strang et al., Reference Strang, Koop, Dupuis-Blanchard, Nordstrom and Thompson2006; Legault and Ducharme, Reference Legault and Ducharme2009; Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Larsson and Athlin2012) and hindered positive family–staff relationships (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Shyu, Lin and Yang2008; Majerovitz et al., Reference Majerovitz, Mollott and Rudder2009). Similarly, when exploring resident and family care-giver involvement in a specific type of FI, that of shared decision making, Mariani et al. (Reference Mariani, Vernooij-Dassen, Koopmans, Engels and Chattat2017) found a circuitous influential factor. The degree of families’ usual involvement in relatives’ lives and in their care facilitated further FI in shared decision making.

Desire for both participation and recognition as a care partner increased involvement (Caron et al., Reference Caron, Griffith and Arcand2005; Port et al., Reference Port, Zimmerman, Williams, Dobbs, Preisser and Williams2005; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ruzin, Graneheim and Lindgren2014), while poor, inadequate, unstructured family–staff communication inhibited participation (Bramble et al., Reference Bramble, Moyle and McAllister2009; Stirling et al., Reference Stirling, McInerney, Andrews, Ashby, Toye, Donohue, Banks and Robinson2014; Lethin et al., Reference Lethin, Hallberg, Karlsson and Janlov2016). Changes in resident adjustment and mood could both motivate involvement or result in fewer visits (Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006; Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Larsson and Athlin2012), although when specifically explored, higher agitation was not associated with family visits (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Barber, Marston, Rapaport, Livingston, Cousins, Robertson, La Frenais F and Cooper2017).

Involvement in resident personal care and monitoring of staff reduced as confidence in care delivery increased. However, as a resident's cognitive impairment, physical symptoms and BPSD deteriorated, family visits and the likelihood of participation in care planning increased (Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006; Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Larsson and Athlin2012; McCreedy et al., Reference McCreedy, Loomer, Palmer, Mitchell, Volandes and Mor2018). In contrast, other studies found no difference in visit frequency as a function of dementia severity (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Zimmerman, Reed, Sloane, Beeber, Washington, Cagle and Gwyther2014) or length of placement (Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006; Legault and Ducharme, Reference Legault and Ducharme2009).

Family care-giver characteristics such as age, gender and education level, and resident characteristics such as ethnicity and payment method (state or other/private) appeared to be important participation factors. However, intergenerational dynamics and factors influencing grandchild involvement seemed surprisingly absent. Helgesen et al. (Reference Helgesen, Athlin and Larsson2015) found: perceptions of the importance of FI is varied based on education level, relevant knowledge held about residents is higher amongst females and elder family members appear to attract more offers of support from staff. McCreedy et al. (Reference McCreedy, Loomer, Palmer, Mitchell, Volandes and Mor2018) found associations between family participation and the following: residents being of black heritage, requiring an interpreter to communicate, level of ADL dependencies, displayed behaviours (e.g. aggression) and other health factors.

However, these factors are not all included in Table 7 as whether they enable or prohibit FI and increase or decrease visits is still unknown and contrasting results are evident. For instance, given trust and communication are known to be key in FI, studies found no significant link between FI and education and trust in staff (Boogaard et al., Reference Boogaard, Werner, Zisberg and Van der Steen2017) or education and quality of communication (Toles et al., Reference Toles, Song, Lin and Hanson2018). An association between ethnicity and lower trust in health professionals and a link between involvement in care and overall trust, were found (Boogaard et al., Reference Boogaard, Werner, Zisberg and Van der Steen2017).

FI was facilitated when care home policies, practice and physical environment overtly considered family participation. Higher social worker ratios were linked to higher family participation though care home characteristics (including quality ratings) did not explain the majority of variance in FI between care homes (McCreedy et al., Reference McCreedy, Loomer, Palmer, Mitchell, Volandes and Mor2018). When staff were encouraged to: offer opportunities to families to be involved, foster personalised, open relationships and raised (and were trained to raise) difficult topics such as end-of-life goals, family care-givers reported being able to engage and access support (Port et al., Reference Port, Zimmerman, Williams, Dobbs, Preisser and Williams2005; Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006; Bramble et al., Reference Bramble, Moyle and McAllister2009; Majerovitz et al., Reference Majerovitz, Mollott and Rudder2009; Ampe et al., Reference Ampe, Sevenants, Smets, Declercq and Van Audenhove2016; Reid and Chappell, Reference Reid and Chappell2017; Carter et al., Reference Carter, McLaughlin, Kernohan, Hudson, Clarke, Froggatt, Passmore and Brazil2018; Forsund and Ytrehus, Reference Forsund and Ytrehus2018).

Toles et al. (Reference Toles, Song, Lin and Hanson2018) found families rated quality of communication as poor when important end-of-life topics were omitted from communication. However, as Ampe et al. (Reference Ampe, Sevenants, Smets, Declercq and Van Audenhove2016) discovered, when comparing policy to practice, staff tend to only use baseline skills when involving families; approximately half of the staff–family conversations about advanced care planning in their study were not substantive. Mariani et al. (Reference Mariani, Vernooij-Dassen, Koopmans, Engels and Chattat2017) found both over- and underregulation, and a lack of funding, impacted implementation of a decision-making framework aimed at improving family (and resident) participation.

Summary

A wide array of types of FI and factors that influence FI following placement of a relative living with dementia have been identified. When grouped, seven themes forming part of a non-linear process stood out. Cross-country comparisons showed both similarities and differences. Identified FI types fit neatly with PCC and FCC principles, however, some matches are less convincing than others. There is a complex, multi-dimensional and evolving interplay across: family-assigned roles, the activities in which families participate, the nature of family and staff participation preferences, and the interactions between the care home (environment, culture, policies and systems) and the three parties (families, residents and staff).

Discussion

What do we know now that we did not know in 2005?

FI activities are broader in range than originally identified and differences between types are now distinct and better understood. New types and sub-types of involvement have been highlighted in Table 4 alongside the 11 overarching types of non-dementia-specific FI that were understood in 2005. Emphasis has moved beyond personal, instrumental, preservative and socio-emotional care activities (Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006).

Seven themes of FI activities shown in Figure 2 have been proposed along with a non-linear process of FI undertaken with varying theme emphases throughout the duration of a resident's placement. Being an advocate, spokesperson and guardian were repeatedly identified as important involvement activities and roles (see Table 4); a contrast to 2005 when advocacy was not a prominent feature (MacDonald, Reference MacDonald2005). This change concurred with recent literature (Graneheim et al., Reference Graneheim, Johansson and Lindgren2014; Petriwskyj et al., Reference Petriwskyj, Gibson, Parker, Banks, Andrews and Robinson2014).

Now, a distinction is made between active advocate involvement and the more passive visitor involvement (Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Larsson and Athlin2012). The discrete themes of FI types also reflect this, e.g. Participate in care delivery (core needs) is distinct from Supervise, influence and direct care or Monitor care, both of which require proactive forms of engagement.

Within a new landscape of care partnerships, positive family–staff relationships are no longer enough; families seek personalised, meaningful relationships with staff and recognition of their role as a care partner (Caron et al., Reference Caron, Griffith and Arcand2005; Aveyard and Davies, Reference Aveyard and Davies2006; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Shyu, Lin and Yang2008; Bramble et al., Reference Bramble, Moyle and McAllister2009). Consistent with other reviews (Gaugler, Reference Gaugler2005; Petriwksyj et al., Reference Petriwskyj, Gibson, Parker, Banks, Andrews and Robinson2014), the majority of families wish to remain involved and become more involved with care homes following placement of their relative.

It is likely that the expansion in types of FI are driven by a number of varied factors. The increased publicity about the inner workings of residential institutions and media spotlight on examples of negligence or abuse has led to families’ increased awareness of what can go wrong when they are not involved or do not retain a level of supervision within care homes. Similarly, the CQC (2015), NICE (2018) and recommended care home guidelines place emphasis on encouraging FI. In cultures where the individual is central, society norms mean fewer intergenerational families live together for support, however, value is still placed on individuals’ rights, dignity, identity and perspective regardless of their health status. Therefore, families may wish to uphold these norms through advocacy, protect their own mental health as they and their relative adjust, and it is likely they also wish to model involvement with care homes for younger family members in order to safeguard their own care in the future. Similarly, families recognise their rights to involvement and increasingly expect to be accommodated by care home policy and staff.

Influences on FI

This review confirmed that the array of factors already known to influence FI with care homes also pertain to FI following placement of a relative living with dementia.

However, additional variables that prohibit or provide motivation for involvement were also identified. In line with another review (Petriwskyj et al., Reference Petriwskyj, Gibson, Parker, Banks, Andrews and Robinson2014), understaffing and unhelpful staff working patterns hindered participation (Bramble et al., Reference Bramble, Moyle and McAllister2009; Majerovitz et al., Reference Majerovitz, Mollott and Rudder2009) and involvement in a shared decision-making framework, as did competing demands on families (Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006). Akin to recent literature (Graneheim et al., Reference Graneheim, Johansson and Lindgren2014; Petriwskyj et al., Reference Petriwskyj, Gibson, Parker, Banks, Andrews and Robinson2014), quality of staff–family relationships (Bramble et al., Reference Bramble, Moyle and McAllister2009), staff offers of FI opportunities and assistance (Reid and Chappell, Reference Reid and Chappell2017), as well as families’ perception that they are recognised as a care partner (Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ruzin, Graneheim and Lindgren2014) with unique knowledge of the resident, all facilitate involvement.

In a recent study conducted by Lao et al. (Reference Lao, Low and Wong2019), Chinese residents (though not specific to dementia) highlighted influencing factors similar to those found in this review, including family commitments, age, financial concerns, family–resident relationship and limited visiting hours. Importantly, and in contrast to Etkind et al. (Reference Etkind, Bone, Lovell, Higginson and Murtagh2018), only 50 per cent of families with relatives living with dementia consider their involvement to be crucial for resident wellbeing after placement (Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Athlin and Larsson2015) and this perception alone may be a significant contributing factor to why some families engage less or do not get involved with care homes.

PCC and FCC

While few gaps were found between FI types and PCC/FCC frameworks, FI types were assigned applying an assumption that core types of involvement (that may be perceived as more threatening or less welcome in partnership) such as monitoring, supervision and evaluation of care were included in overarching PCC philosophy about family carers. If this assumption is inappropriate then important types of FI are not yet clearly and fully represented by current PCC principles.

Why might that be? It is possible that some families do not value PCC or the same principles and this could be related to cultural or family dynamic concerns. Alternatively, families may not have been encouraged to learn about and engage in PCC/FCC-based activities that are known to be effective, so are relying solely on their own ideas about how to remain involved. Further research to redefine and enhance PCC/FCC is required.

Why are PCC/FCC principles of Individuality, Person's perspective and Information sharing not represented by the types of FI that the literature shows families with residents living with dementia in care homes undertake? Could it be that pragmatic application of care home policies are yet to, or inconsistently, reflect these principles? After all, implementing PCC into daily practice is challenging (Vernooij-Dassen and Moniz-Cook, Reference Vernooij-Dassen and Moniz-Cook2016); or possibly more likely, few interventions to target these principles have been adopted and, as Fazio et al. (Reference Fazio, Pace, Flinner and Kallmyer2018) point out, more research is required.

When a patient- and family-centred care approach was used, expressly where contact with family and family visits were encouraged, opportunities for FI and assistance was offered and family-oriented policies were applied, a positive impact on FI ensued; FI was facilitated and stimulated. Without a FCC approach, FI was prevented and discouraged (for paper references, see the first row of Table 7). Interestingly, care home use of FCC approaches did not necessarily mean families visited or increased their contact; studies showed contrasting results. Therefore, when care homes adopt and practise PCC with a focused FCC component, families may fulfil some of the resource requirements that care homes anticipate needing, now and for the future, yet employ a ‘light touch’, one that incorporates staff needs and respects staff time constraints. In other words, families and staff would operate in a manner of personalised partnership, the very approach that families seek.

Strengths and limitations

Three databases and three researchers were used for the search. Extensive hand searches were completed to ensure search strategy bias was minimised. Four researchers and a consensus approach were used for paper appraisal. Five of the 50 papers included in reviews used for comparison matched our included studies. To limit reporting bias, findings that corroborate and contrast in evidence to our findings have been described when alternative papers within the reviews were cited.

The MMAT (Pluye et al., Reference Pluye, Robert, Cargo, Bartlett, O'Cathain, Griffiths, Boardman, Gagnon and Rousseau2011) has accrued positive evaluation and evidence of content validity and reliability (Crowe and Sheppard, Reference Crowe and Sheppard2011; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Pluye, Bartlett, Macaulay, Salsberg, Jagosh and Seller2012). It has been used worldwide for at least 50 reviews. As further improvements are recommended (Souto et al., Reference Souto, Khanassov, Hong, Bush, Vedel and Pluye2015), caution was exercised by selecting 25 papers with studies of various designs to be appraised with the Kmet et al. (Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook2004) appraisal tools. No obvious differences in appraisal between the two tools were apparent; a paper with a low Kmet et al. (Reference Kmet, Lee and Cook2004) score was also found to have a low MMAT rating.

Most studies investigated a single specific topic of participation or included involvement measures and did not directly explore involvement types or influences. Therefore, in addition to care-giver stressors that are not the focus of this review, the identified types of and influences on involvement, while numerous, may be incomplete. However, this is the only known systematic review to consider types and influences of FI exclusively in relation to dementia, therefore authors have confidence that the tables displayed are useful and comprehensive.

Implications for clinical practice

It was important to explore types of FI in order to establish if the activities that families are involved in with care homes do in fact reflect the PCC and FCC principles espoused as gold standard. Similarly, to build family profiles of involvement and ensure each family is supported by care homes in a manner conducive to their circumstances, it was important to investigate which factors influence FI and the nature of that influence. This research topic also allowed for an insight into whether a PCC approach created a positive or negative impact on FI.

Staff and families supporting a resident living with dementia can now be confident there is a good fit of family activities to PCC and FCC principles and that employment of family-centric principles within PCC positively influence FI. Exploring types of FI was useful to distinguish seven themes of participation activities. Figure 2 of themes and Table 7 of influencing factors form a framework for staff–resident–family discussion and agreement. This framework reaches well beyond family decisions about medical care and extends to family influence on policy and interventions. Care homes should not be surprised when families seek engagement in macro-level activities, and when care homes need resources for care quality improvement projects families are a likely source of willing contributors.

Family roles and involvement are often dynamic and ambiguous (Graneheim et al., Reference Graneheim, Johansson and Lindgren2014; Petriwskyj et al., Reference Petriwskyj, Gibson, Parker, Banks, Andrews and Robinson2014). Expectations for involvement differ for each family (Caron et al., Reference Caron, Griffith and Arcand2005; Reid and Chappell, Reference Reid and Chappell2017), adding more complexity to FI after relative placement. Positive staff–family partnerships are likely if, at the outset of placement, staff enquire about family expectations, hopes for involvement and provide information about how FI is promoted within the care home. This approach, ideally underpinned by an enhanced (well-defined and fully applied) FCC framework, will help both families and staff to build an individualised family profile of involvement that can evolve over time, avoid ambiguities about roles and types of involvement each party will participate in, learn about the factors that immediately influence a specific family's involvement and model a collaborative, transparent relationship.

The commonly used description of FI (Gaugler, Reference Gaugler2005; Reid et al., Reference Reid, Chappell and Gish2007) could be updated. FI may be more accurately described as a multi-dimensional construct that can entail visiting, advocacy, supervising, monitoring and evaluating care, development of care partnerships and foundation care (personal, instrumental, preservative and psycho-social). This description better reflects the range and types of involvement that are important to families.

Definitions of PCC are not yet optimally fit for purpose and could benefit from being more explicit. Future guidelines for PCC in dementia should state FCC characteristics or reconcile FCC and PCC components in a consistent and clear manner. At the research, policy and practical application levels, stakeholders may interpret the meaning of principles differently. For example, FCC Participation and Collaboration may be conflated or operationalised differently leading to incomparable and inconsistent outcome recording.

FI types Evaluation, Supervision and Monitoring of care home service and staff may be encompassed by the overarching PCC point, The importance of taking into account the needs of carers, supporting and enhancing carer input. Alternatively, one improvement proposed is to acknowledge and embrace openly these FI types within the descriptions of PCC and FCC principles as they are a fundamental part of partnership. New principle descriptions may decrease ambiguities, clarify expectations, and ultimately improve communication and quality of care.

Future research

UK-, wider European-, Asian- and southern hemisphere-based research in FI with care homes, specific to dementia, remains underrepresented. Attitude to long-term care and care culture differs across localities (van der Steen, Reference van der Steen, Arcand, Toscani, de Graas, Finetti, Beaulieu, Brazil, Nakanishi, Nakashima, Knol and Hertogh2012; Killett et al., Reference Killett, Burns, Kelly, Brooker, Bowes, La Fontaine, Latham, Wilson and O'Neill2016; Mariani et al., Reference Mariani, Vernooij-Dassen, Koopmans, Engels and Chattat2017; Ludecke et al., Reference Ludecke, Bien, McKee, Krevers, Mestheneos, Di Rosa, von dem Knesebeck and Kofahl2018) and the studies in this review did not represent a wide enough range of cultures to establish cultural and regional nuances in types of FI and factors influencing FI. Instead, hints of commonalities and differences were apparent and warrant further investigation.

For example, pre-existing and blind trust by some families towards care homes reported by a Canadian study and families’ active recognition and acceptance of care homes raised in a Taiwanese study, appear to be similar. In contrast, a difference was indicated regarding the type of FI involving Supervising, influencing and directing care; studies from the USA, UK and Australia highlighted this theme more than studies from Canada, Asia, Europe and Scandinavia.

FI studies in underrepresented locations featuring a wide range of cultures will address the evidence imbalance, uncover differences in country and regional FI preferences (that support culturally sensitive, person- and family-centred care), and promote deeper understanding of inter-country and inter-culture barriers and facilitators of FI.

It is possible that underrepresentation of many locations is not purely due to a difference in religious, cultural social norms or availability of care homes. Life expectancy in Africa, Asia and South America is lower than Europe, Oceania and the USA (United Nations, 2017). Consequently, with fewer people living to an age when dementia is most likely to be diagnosed (Rizzi et al., Reference Rizzi, Rosset and Roriz-Cruz2014), dementia research may be of lower priority in some regions.

Intergenerational factors specifically influencing FI with care homes, relating to residents living with dementia, do not appear to have been studied. Four papers briefly mentioned grandchildren, exclusively when describing participant characteristics (Gladstone et al., Reference Gladstone, Dupuis and Wexler2006; Reinhardt et al., Reference Reinhardt, Boerner and Downes2015; Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Barber, Marston, Rapaport, Livingston, Cousins, Robertson, La Frenais F and Cooper2017; Walmsley and McCormack, Reference Walmsley and McCormack2017). Only one paper compared different generations (spouse to adult child) involvement across multiple domains (Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Athlin and Larsson2015), however, the youngest participant was 34 years of age. Another paper mentioned the need to clarify how differing relationship ties explain differences in decision making (Caron et al., Reference Caron, Griffith and Arcand2005). Future FI research needs to include care home settings, residents living with dementia and family participants under the age of 18.

Uninvolved and scarcely involved families rarely featured in the study samples. They may account for as many as 15 per cent of families (missing data cases reported by Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Barber, Marston, Rapaport, Livingston, Cousins, Robertson, La Frenais F and Cooper2017). Research with families who have no or minimal involvement after placement of a relative living with dementia would ensure we understand if families have been discouraged from participation, have mismatched expectations about how they might participate, and whether opportunities for involvement exist or if there are other unknown influences preventing involvement. Studies with this sample group are likely to be challenging (Helgesen et al., Reference Helgesen, Athlin and Larsson2015), however, ignoring this sample can lead to bias and hinder a complete understanding (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Dieppe, MacIntyre, Michie, Nazareth and Petticrew2013).

The literature would be enhanced by dementia-specific research exploring optimal levels of FI and conditions in which high levels of FI result in negative psycho-social, quality-of-life and care outcomes for residents. Development and evaluation of effective methods of communicating this evidence to families and negotiating a new involvement profile while maintaining a positive, collaborative, partnership approach would also be necessary.

To understand better the associations and interactions between specific factors that influence FI, further studies with consistent, robust multi-source measures of FI, large sample sizes and mixed-method designs would be appropriate. Drawing credible conclusions would then be feasible.

Finally, in the Introduction, the point was made that FI was key to transparency between patient, families and care home staff. It was interesting to discover that transparency as a distinct construct was not specifically examined in any of the included studies. One study investigating advocacy found that staff transparency about incidents was critical in the development of trust in family–staff relationships (Legault and Ducharme, Reference Legault and Ducharme2009). This finding is harmonious with the UK's duty of candour regulation which aims to ensure an open, honest and transparent culture in care provision settings (CQC, 2015). Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Zimmerman, Reed, Sloane, Beeber, Washington, Cagle and Gwyther2014) suggested increased transparency in roles and involvement would promote family–staff partnership.

Factors that negatively influence FI included inadequate information provision and staff communication, involvement not always being encouraged, family perceptions that staff are not doing their best, and lack of respect for or blind trust in staff. All of these are likely to hinder transparency, advocacy and relationships. Trust, openness and an inclusive environment are important factors in involvement (Petriwskyj et al., Reference Petriwskyj, Gibson, Parker, Banks, Andrews and Robinson2014; Jakobsen et al., Reference Jakobsen, Sellevold, Egede-Nissen and Sorlie2019) and our review indicates there is a growing emphasis on open family–staff relationships and care home encouragement of involvement through policies and practice. The literature base may benefit from studies that go beyond investigating trust and openness. Instead, specific exploration of transparency in care homes, relating to families and residents living with dementia, may ensure further enhancement of FCC framework and related interventions.

Conclusions

This dementia and care home-specific review explored types of FI and factors influencing FI. It also compared PCC and FCC principles to how families are (or wish to be) involved with residential care providers. Sound progress in our understanding has been made over the last 14 years and since publication of Gaugler's (Reference Gaugler2005) seminal paper. However, many findings remain under-corroborated and gaps in the evidence exist.

Key messages include (not exclusively):

(1) An invitation to participate is not enough; opportunities to undertake activities families expect to be involved in is likely to influence their level of engagement and their successful integration as a care partner.

(2) There are seven themes of FI activities and individual types of FI that appear to fit well with current PCC and FCC principles. Despite this, more and specific clinical application and family-centred research is required. Exploration of inter-family variation, how and why the same influencing factor can impact FI both negatively and positively across and within families would be helpful.

(3) There is a large, diverse range and complexity of factors influencing participation, including families’ varied perception of the importance of their involvement for resident wellbeing.

(4) Intergenerational factors have yet to be studied.

(5) Many countries, regions and cultures are underrepresented in the literature base.

(6) Improved definitions of FI and PCC are proposed.

A final thought, while the coronavirus pandemic continues to impact resident and family wellbeing negatively, it is not a time to step back from advancing FI principles. There is a need to adapt and use creative methodologies, including technology, to progress FI at all levels of care. This systematic review and the second paper in this series (Interventions promoting family involvement with care homes following placement of a relative living with dementia: A systematic review. (Hayward et al., Reference Hayward, Gould, Palluotto, Kitson, Fisher and Spector2021) provide a comprehensive view of FI, including a proposed new definition, the nature of FI and process involved, how FI relates to PCC and FCC principles, measures of FI, the impact of FI on residents’ wellbeing and how FI is being promoted in care homes. Together, the papers support researchers and care home providers to make informed decisions in the dementia field.

Author contributions

JH was the main researcher involved in all aspects of the study from design, paper search, selection, appraisal, analysis to write up. CG was involved in paper search, selection, appraisal and analysis. EP was involved in paper selection, appraisal and analysis. Both CG and EP provided editorial suggestions. ECK was involved in paper appraisal. AS supervised the project overall, provided expert advice throughout and edited the paper.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was not required for this review paper.