Introduction

The prognosis of patients suffering from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is still unsatisfactory despite the numerous improvements in antithrombotic therapy and innovations in reperfusion strategies. A large cohort study conducted in China reported that the 1-year rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in AMI patients discharged alive was 7.7% (Shang et al., Reference Shang, Liu, Zheng, Ho, Hu, Li and Krumholz2019). Therefore, secondary prevention should be an essential part of the care for patients suffering from AMI because they are at risk of high-mortality rates and poor prognosis. Additionally, it is vital to identify the high-risk groups in order to optimize secondary prevention strategies.

In addition to traditional risk factors, psychological aspects have emerged as potential risk elements for adverse cardiovascular events in cardiac patients. Type D (distressed) personality, formulated by Denollet, is a stable character trait that combines negative affectivity (NA, the tendency to experience negative emotions) and social inhibition (SI, the tendency to inhibit self-expression during social interaction) (Beutel et al., Reference Beutel, Wiltink, Till, Wild, Munzel, Ojeda and Michal2012). A previous study proposed that routine screening of Type D personality should be done in order to identify CAD patients at a high risk of poor psychological and physical health (Kupper & Denollet, Reference Kupper and Denollet2018). This has led to Type D personality being emphasized in the European Cardiovascular Prevention guidelines since 2016 (Authors/Task Force et al., Reference Piepoli, Hoes, Agewall, Albus, Brotons and Zamorano2016). Furthermore, a recent long-term follow-up study reported that Type D personality was an independent predictor of MACEs in patients suffering from AMI (Imbalzano et al., Reference Imbalzano, Vatrano, Quartuccio, Ceravolo, Ciconte, Rotella and Mandraffino2018). However, contrary findings were reported by a study which examined the relationship between Type D personality and all-cause mortality in AMI patients (Conden et al., Reference Conden, Rosenblad, Wagner, Leppert, Ekselius and Aslund2017). Some scholars have argued that these inconsistencies can be partly attributed to the different approaches used to operationalize the Type D personality effect. Recent studies have reported that the methods commonly used to classify people in personality subgroups are based on whether the patients score above or below a particular cut-off on the continuous NA and SI traits, thus, they may reduce the sensitivity of tests and produce spurious association (Coyne & de Voogd, Reference Coyne and de Voogd2012; Lodder, Reference Lodder2020). Some researchers have recommended that the Type D personality should be analyzed using the continuous interaction method including the NA and SI effects (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Williams, O'Connor, Howard, Hughes, Johnston and O'Carroll2009). Therefore, different methods for analyzing the Type D personality should be applied in order to better understand the effect of Type D personality on cardiovascular outcomes.

Depression is a common and persistent condition in AMI survivors (AbuRuz & Al-Dweik, Reference AbuRuz and Al-Dweik2018). In addition, numerous studies have been conducted to determine the association between depression and adverse cardiac outcomes. A recent large-scale study reported that depression was independently associated with mortality in patients diagnosed with AMI (Cocchio et al., Reference Cocchio, Baldovin, Furlan, Buja, Casale, Fonzo and Bertoncello2019). Furthermore, the results obtained in a recent prospective cohort study indicated that the association of depression with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality was stronger among men compared to women (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Yu, Liu, He, Lv and Guo2020). Therefore, monitoring depression can help to predict the cardiovascular events in patients suffering from cardiovascular diseases.

Extensive evidence exists on the link between psychological risk factors and adverse outcomes in cardiovascular patients. However, reports on the prospective relationship between cardiovascular prognosis and Type D personality and/or depression are limited. Moreover, the idea of overlapping constructs between Type D personality and depression has resulted in several controversies. For instance, a previous study reported that the negative affectivity subscale of the Type D personality and depressive symptoms were largely overlapping constructs (Ossola, De Panfilis, Tonna, Ardissino, & Marchesi, Reference Ossola, De Panfilis, Tonna, Ardissino and Marchesi2015). Nonetheless, recent studies have demonstrated that Type D personality is a stable personality trait with a tendency to develop emotional distress including depression (van Dooren et al., Reference van Dooren, Verhey, Pouwer, Schalkwijk, Sep, Stehouwer and Denollet2016). Therefore, there is a possibility that the coexistence of Type D personality and depression in AMI patients may have a worse effect on cardiovascular prognosis.

Furthermore, previous studies conducted in Chinese populations found that there was a sex difference in the association between depression and mortality (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Yu, Liu, He, Lv and Guo2020). Moreover, Kupper and Denollet (Reference Kupper and Denollet2018) reported that sex differences in Type D personality individuals were associated with a specific combination of cardiovascular risk markers (van Montfort, Mommersteeg, Spek, & Kupper, Reference van Montfort, Mommersteeg, Spek and Kupper2018), thereby suggesting that the cardiac risk conferred by Type D personality may change with gender. Therefore, this individual patient-based cohort study of AMI patients will examine whether gender can explain heterogeneity in the prognostic effect of Type D personality and depression.

The main aim of this study was to investigate the combined effects of Type D personality and depression on cardiovascular prognosis in AMI patients. In addition, the study also explored the possible influence of sex.

Methods

Study design and populations

This prospective AMI cohort study was established in 2017, with the support of the National Key R&D Program of China. A total of 3704 AMI patients admitted at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University between February 2017 and September 2018 were eligible for enrollment in the study. Patients aged between 18 and 75 years were included in the study. However, the study excluded patients who had severe comorbid medical disorders (n = 21) or died before discharge (n = 51), had a history of coronary artery bypass graft (n = 7) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (n = 32), had severe heart failure (n = 11), and were unable to provide informed consent (n = 6) or complete the questionnaires (n = 4).

At baseline, patients were asked to provide demographic information and independently complete tests for Type D personality and depression. Clinical information including patients’ past medical history, biochemical index, and stent data at baseline was obtained from the medical records. During the follow-up, information on cardiac death, recurrent non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), revascularization, and stroke was collected using hospital records and telephone interviews at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after discharge. Patients were advised to return for follow-up angiographic evaluation in instances where indications of ischemic events occurred. Four patients were excluded from our analyses because they could not be contacted by phone during follow-up, which left us with 3568 patients who were enrolled in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. Moreover, written informed consent was obtained from all patients before being enrolled in the study.

Common clinical and laboratory assessments

We selected demographic and clinical variables that could influence cardiovascular prognosis based on previous research (Guerrero-Pinedo et al., Reference Guerrero-Pinedo, Ochoa-Zarate, Salazar, Carrillo-Gomez, Paulo, Florez-Elvira and Velasquez-Norena2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Gao, Zhao, Li, Chen and Lin2018). The variables included age, gender, type of AMI, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and smoking. On the contrary, the laboratory data consisted of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), blood glucose, and high sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). Quantitative coronary angiography was used to measure the stent data including the total stent length and minimum stent diameter when they received stent treatment. All the data management and quality control were performed using an electronic data capture system (Crealife Technology, Beijing, China).

Assessment of Type D personality

Type D personality was assessed at baseline using the 14-item Type D Scale (DS14), which is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (false) to 4 (true). The DS14 comprises two 7-item measures; namely, NA and SI. A cut-off of 10 or more on both subscales denotes patients with a Type D personality (Denollet, Reference Denollet2005). The DS14 is reliable, with a Cronbach's α = 0.88/0.86 and a test–retest reliability r = 0.72/0.82 for the NA and SI subscales, respectively (Denollet, Reference Denollet2005). Recent studies have demonstrated that Type D personality is better represented as a dimensional construct as opposed to a categorical construct (Lodder, Reference Lodder2020). Thus, this study analyzed the NA and SI subscales, and the statistical interaction between the two.

Assessment of depression

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Furlanetto, Mendlowicz, & Romildo Bueno, Reference Furlanetto, Mendlowicz and Romildo Bueno2005). It is worth noting that a previous study proved that the BDI has a prognostic value in cardiac populations (Pimple et al., Reference Pimple, Lima, Hammadah, Wilmot, Ramadan, Levantsevych and Vaccarino2019). Patients were asked to rate the severity of each item on a scale ranging from 0 to 3 based on their experiences. The total scores ranged from 0 to 39 and higher scores reflected more severe depressive symptoms. The study considered depression to be a BDI score ⩾16 based on previous reports (Kabutoya, Hoshide, Davidson, & Kario, Reference Kabutoya, Hoshide, Davidson and Kario2018). The dichotomized measures and BDI score were included in our analysis.

Cardiovascular outcomes and medication adherence

The primary end points were MACEs including cardiac death, recurrent non-fatal MI, revascularization, and stroke at 2-year follow-up. On the contrary, the secondary outcome was ISR, which is defined as a stenotic lesion ⩾50% occurring in the segment inside the stent, 5 mm proximal or distal to the stent (Dangas et al., Reference Dangas, Claessen, Caixeta, Sanidas, Mintz and Mehran2010). Moreover, an independent clinical event committee was established to adjudicate all the reported events up to 24 h. For patients with multiple events, the first one was selected for statistical modeling.

All patients were required to take long-term aspirin (100 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/d) or ticagrelor (180 mg/d) for at least 12 months. In this study, pharmacy-based proportions of the days covered (the number of days for which medication was supplied divided by the total number of days in the time period) were used to quantify adherence to antiplatelet therapy during the follow-up period. Non-adherence was indicated when the proportion of days covered was ⩽0.50 (Cetin et al., Reference Cetin, Ozcan Cetin, Kalender, Aydin, Topaloglu, Kisacik and Temizhan2016).

Statistical analysis

The descriptive data obtained in this study were presented as means. Standard deviations (s.d.s) were used for continuous data, while frequencies and percentages, n (%), were used for categorical data. Differences between multiple groups were determined using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables.

Furthermore, the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of MACE and ISR based on the combined effects of Type D personality and depression, with 11 covariates and their 2-way interactions as independent variables (age, gender, smoking, diabetes, the type of AMI, hs-CRP, LDL-C, minimum stent diameter, total stent length, aspirin adherence, and clopidogrel/ticagrelor adherence) (Ang et al., Reference Ang, Behnamfar, Palakodeti, Lin, Pourdjabbar, Patel and Mahmud2017; Guerrero-Pinedo et al., Reference Guerrero-Pinedo, Ochoa-Zarate, Salazar, Carrillo-Gomez, Paulo, Florez-Elvira and Velasquez-Norena2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Gao, Zhao, Li, Chen and Lin2018). Moreover, the cluster-mean centering age and contrast coding of −0.5/0.5 for dichotomous variables was used in the Cox regression analysis to ensure variances between groups were equal. Additionally, the subgroup analysis models were used to directly explore the effect of gender on the association between Type D personality + depression, MACE, and ISR, and we performed the multiplicative model to further examine the interaction terms between Type D personality and depression by gender. The cumulative incidence of MACEs was estimated in the subgroups of the Type D personality and depression using the Kaplan–Meier method, followed by comparison with the log-rank test.

We then performed the multivariate regression model using the continuous DS14 scores and BDI scores in order to further examine the validity of Type D personality and depression, the main effect of Type D personality and depression, and their statistical interaction were analyzed in the models. A moderating effect is indicated if the interaction term (Type D personality × depression) is statistically significant after adjusting for covariates and their 2-way interactions. When the interaction was statistically significant, we examined the interaction plot to see how the association between Type D personality and depression interaction and cardiovascular adverse outcome. In addition, the study analyzed the continuous Type D personality measure (interaction of NA and SI z sores) adjusting for the main NA and SI effects, and BDI scores.

All the analyses were performed using SPSS Version 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and R V.3.6.1 statistical software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-tailed p value of <0.01 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

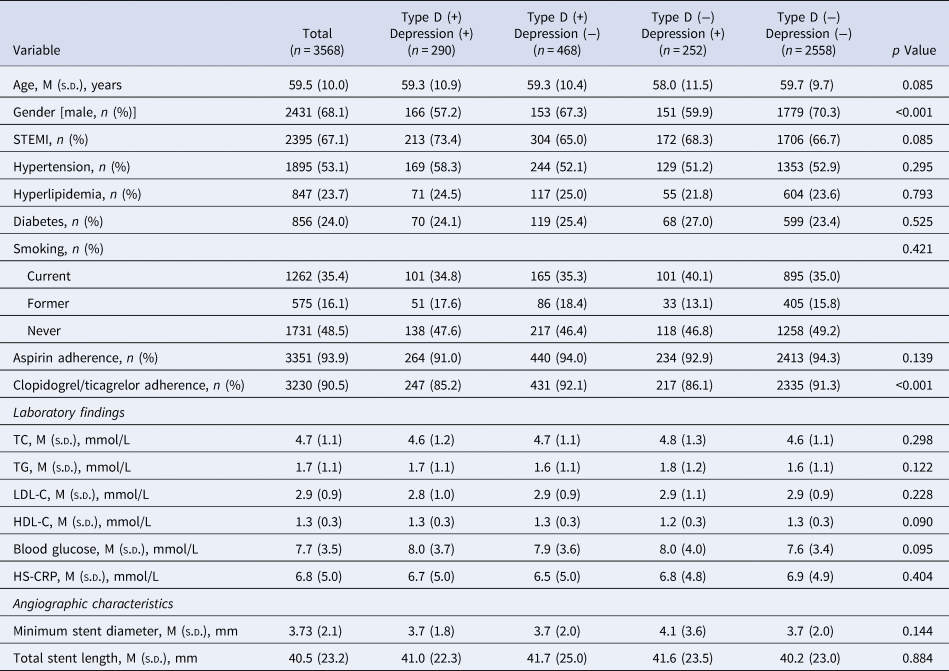

The final sample size included 3568 AMI patients with a mean age of 59.5 years and 68.1% were men. The results indicated that the total prevalence of the Type D personality and depression was 21.2% and 15.2%, respectively. Moreover, there was a significant difference in the incidence of depression between the Type D and non-Type D personality groups (38.2% v. 8.9%, p < 0.001). The breakdown was as follows: 290 (8.1%) participants were in the Type D (+) depression (+) group; 468 (13.1%) belonged to the Type D (+) depression (−) group; 252 (7.1%) fell under the Type D (−) depression (+) group; and 2558 (71.7%) were in the Type D (−) depression (−) group. The clinical characteristics of the four groups are shown in Table 1. Patients with both Type D personality and depression were more likely to be male, and had the least adherence to clopidogrel/ticagrelor treatment during the 2-year follow-up period.

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics by Type D personality and depression groups

STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein-cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein-cholesterol; HS-CRP, High sensitivity-C-reactive protein.

Variable coding form: female = −0.5, male = +0.5; current smoking = −1.0, former smoking = 0, never smoking = +1.0.

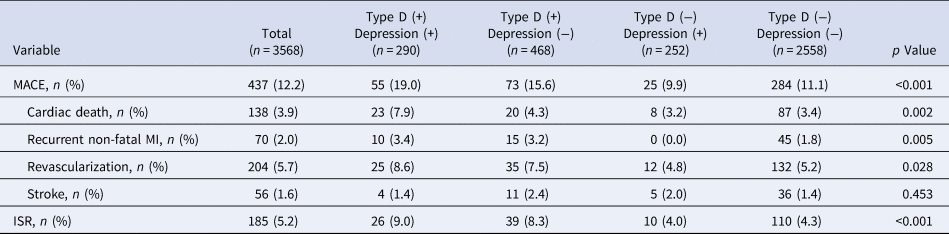

Clinical outcomes during the follow-up period

During the 2-year follow-up period, a total of 437 patients had MACEs including cardiac death (n = 138), recurrent non-fatal MI (n = 70), revascularization (n = 204), and stroke (n = 56), while 185 patients had ISR. The results indicated that the Type D (+) depression (+) and Type D (+) depression (−) groups displayed significantly high percentages of MACEs (19.0% and 15.6%, respectively) and ISR (9.0% and 8.3%, respectively) during the follow-up period (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the Type D (+) depression (+) group displayed the highest rate of cardiac death (7.9%, p = 0.002), and recurrent non-fatal MI (3.4%, p = 0.005), and had an increasing trend of revascularization (8.6%, p = 0.028) during follow-up (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical outcomes by Type D personality and depression groups

MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; ISR, in-stent restenosis.

Predictive value of categorized Type D personality and depression on MACE and ISR

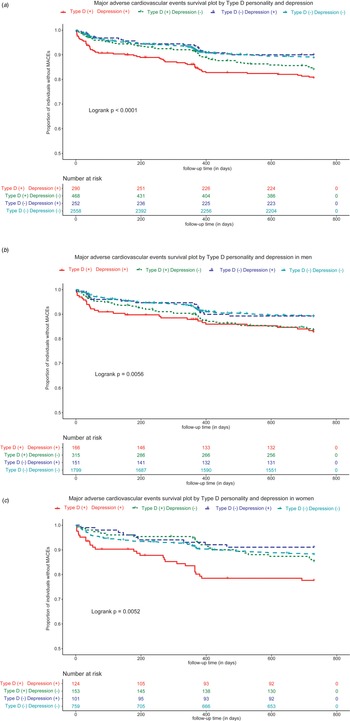

The categorized Type D personality and depression construct was then added to the Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, indicating that Type D (+) depression (+) (HR 3.28; 95% CI 1.74–6.07; p < 0.001) (HR 5.61; 95% CI 3.09–8.28; p < 0.001) and Type D (+) depression (−) (HR 2.73; 95% CI 1.25–2.96; p = 0.010) (HR 3.28; 95% CI 1.85–6.22; p < 0.001) were independent predictors of 2-year MACEs and ISR in all the subjects (Tables 3 and 4), which were obtained after adjusting for independent variables. The Kaplan–Meier plot shown in Fig. 1a highlights the cumulative risk of MACEs in the four groups (p < 0.0001).

Fig. 1 Kaplan–Meier curves showing the cumulative risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) by Type D personality and depression: (a) overall population, (b) men, and (c) women.

Table 3. Association with MACE by Type D personality and depression with categorical approacha

MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; NA, not applicable; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; HS-CRP, High sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

a A MACE was defined as any of the following: cardiovascular death, recurrent myocardial infarction, revascularization, and stroke.

b Type D personality and depression subgroups were entered as dummy variables, and Type D (−) and depression (−) group was the reference group. Type D personality and depression coding: Type D (+) Depression (+) = 0, Type D (+) Depression (−) = 1, Type D (−) Depression (+) = 2, Type D (−) Depression (−) = 3.

Table 4. Association with ISR by Type D personality and depression with categorical approach

ISR, in-stent restenosis; NA, not applicable; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; HS-CRP, High sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

a Type D personality and depression subgroups were entered as dummy variables, and Type D (−) and depression (−) group was the reference group. Type D personality and depression coding: Type D (+) Depression (+) = 0, Type D (+) Depression (−) = 1, Type D (−) Depression (+) = 2, Type D (−) Depression (−) = 3.

Furthermore, the analysis on MACEs was conducted in the subgroups of men and women, which indicated a significant association with gender. The proportion of MACE in men and women subgroups was 290 (11.93%) and 147 (12.93%), respectively. As shown in Tables 3 and 4, the regression analysis results showed that Type D (+) depression (+) (HR 2.41; 95% CI 1.32–5.87; p = 0.001) (HR 4.51; 95% CI 2.59–7.87; p < 0.001) and Type D (+) depression (−) (HR 1.96; 95% CI 1.21–4.07; p = 0.003) (HR 2.22; 95% CI 1.31–3.76; p = 0.003) were independent risk factors for MACEs and ISR in men, while only Type D (+) depression (+) showed a trend for increasing MACEs (HR 1.97; 95% CI 1.02–3.81; p = 0.041) and ISR (HR 2.12; 95% CI 1.38–4.39; p = 0.015) in women. The interaction terms between Type D personality, depression and gender were further calculated in the multiplicative model, demonstrating that the interaction terms between Type D personality and depression by gender was significantly associated with MACE (HR 1.96; 95% CI 1.12–2.18; p = 0.002) (Table 3) and ISR (HR 1.51; 95% CI 1.02–1.98; p = 0.010) after adjusting for other relevant covariates (Table 4). The corresponding Kaplan–Meier plots (Fig. 1b and c) and log-rank tests confirmed that the cumulative event rates of the four groups were significantly different in both male and female patients (p = 0.0056; p = 0.0052).

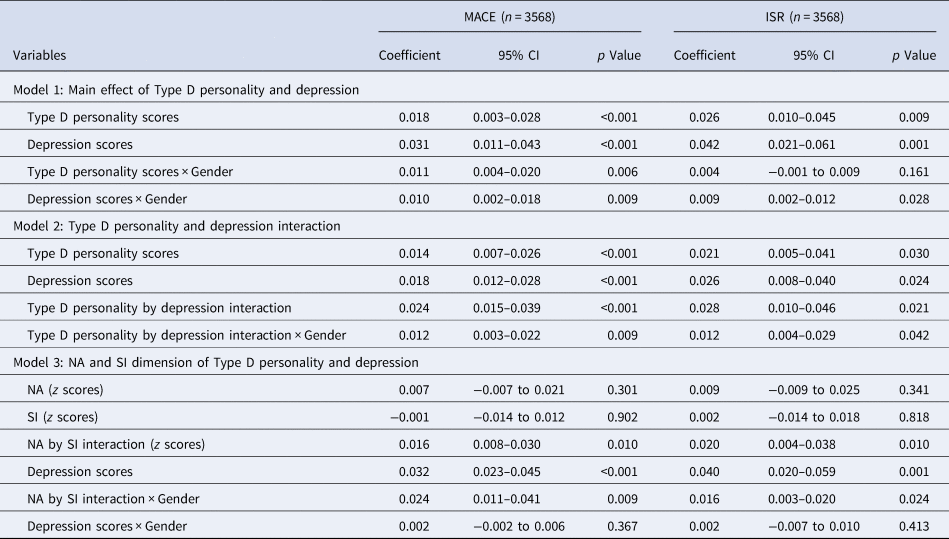

Predictive value of Type D personality and depression scores on MACE and ISR

The continuous DS14 and BDI scores were selected as possible factors in the linear regression model, showing that the main effect of Type D personality (β = 0.018; 95% CI 0.003–0.028; p < 0.001) (β, 0.026; 95% CI 0.010–0.045; p = 0.009) and depression (β, 0.031; 95% CI 0.011–0.043; p < 0.001) (β, 0.042; 95% CI 0.021–0.061; p = 0.001) were independent influencing factors of MACE and ISR (Table 5, Model 1). The product of DS14 and BDI scores was then entered (Table 5, Model 2) to account for the synergistic interaction between Type D personality and depression, indicating that the statistical interaction can significantly predict the occurrence of MACEs (β, 0.024; 95% CI 0.015–0.039; p < 0.001) and have an increasing trend of ISR (β, 0.028; 95% CI 0.010–0.046; p = 0.021). The online Supplementary figure depicts the interaction between Type D personality and depression on MACE and ISR (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), suggesting that the higher the level of depression in patients with high Type D personality, the higher the prevalence of MACEs and ISR (p < 0.01).

Table 5. The association with MACE and ISR by Type D personality and depression with continuous measuresa

MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; ISR, in-stent restenosis; NA, negative affectivity; SI, social inhibition.

a Model adjusted by covariates and their 2-way interactions as independent variables (age, diabetes, smoking, aspirin adherence, clopidogrel/ticagrelor adherence, HS-CRP, LDL-C, minimum stent diameter, total stent length).

Finally, the continuous Type D personality score in Table 5 (Model 3), measured by the interaction of NA and SI scales (β, 0.016; 95% CI 0.008–0.030; p = 0.010) (β, 0.020; 95% CI 0.004–0.038; p = 0.010) and depression scores (β, 0.032; 95% CI 0.023–0.045; p < 0.001) (β, 0.040; 95% CI 0.020–0.059; p = 0.001), was associated with an increased risk of MACEs and ISR.

Discussion

This prospective cohort study indicated that Type D personality, depression, and their combined effect had significant correlations with MACEs and ISR, when analyzed as continuous construct. Furthermore, the combined Type D personality (+) and depression (+) and Type D personality (+) and depression (−) groups were associated with a significantly elevated risk of MACEs and ISR, when analyzed as categorized construct. It is worth noting that these associations were significant in men, and only the combined effect of Type D personality and depression was an independent risk factor for MACEs and ISR in women.

In this study, the prevalence of Type D personality in patients with AMI was 21.2%, which is consistent with the results reported in previous studies (13–31%) (Conden et al., Reference Conden, Rosenblad, Wagner, Leppert, Ekselius and Aslund2017). Several studies have reported that Type D personality is an important predisposing factor for depression (van Dooren et al., Reference van Dooren, Verhey, Pouwer, Schalkwijk, Sep, Stehouwer and Denollet2016). Our results have also shown that Type D personality individuals were significantly more depressed when compared with the non-Type D personality group. This phenomenon might be attributed to the negative coping style of Type D personality individuals when under stress induced by AMI (Sogaro et al., Reference Sogaro, Schinina, Burgisser, Orso, Pallante, Aloi and Fattirolli2010). Alternatively, Type D personality might exert the negative effect of depression through inflammation, cortisol response, and oxidative stress (van Dooren et al., Reference van Dooren, Verhey, Pouwer, Schalkwijk, Sep, Stehouwer and Denollet2016). However, further studies are required to investigate the underlying mechanisms in the relationship between Type D personality and depression.

This study investigated the relationship between Type D personality, depression, and adverse outcomes using different analytical methods. First, we have shown that patients with Type D personality but not depression were associated with 1.42 odds of MACEs and 2.72 odds of ISR in a categorized construct. Furthermore, the odds for MACEs and ISR in the Type D personality and depression groups were much higher. Second, we analyzed the main effect and combined effect of Type D personality and depression as continuous variables. The results indicated that Type D personality and depression were both risk factors for adverse outcomes, and the interaction between the two variables is more effective at predicting poor prognosis. Therefore, these results indicate that patients complicated with depression and Type D personality are a high-risk group with adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

The results obtained in this study have also shown that the relationship between the Type D personality + depression group and Type D personality + non-depression group, and ISR may partially explain the high risk of MACEs in the two groups. Additionally, the linear regression models showed that the combined effect of NA and SI scales was correlated with MACEs and ISR. Previous intravascular imaging research reported that Type D personality was associated with increased risk of coronary vulnerable plaques (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhao, Gao, Li, Liu, Chen and Lin2016) and in-stent neoatherosclerosis (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Yu, Gao, Cao, Tao, Yu and Lin2019), which were the key pathophysiologic mechanisms of acute coronary disease. These findings support the biological plausibility of using Type D personality as a cardiac risk marker and highlight the Type D personality-associated risk estimate, which was hypothesized to work through vascular-specific pathways. The fact that all-cause mortality was chosen as the endpoint in previous Type D personality studies may account for the null findings reported in the studies (Conden et al., Reference Conden, Rosenblad, Wagner, Leppert, Ekselius and Aslund2017; Coyne et al., Reference Coyne, Jaarsma, Luttik, van Sonderen, van Veldhuisen and Sanderman2011). Therefore, the findings obtained in this study suggest that the selection of the endpoint may be important for determining the psychological outcomes.

Behavioral factors and biological pathways may be the mechanisms through which Type D personality and depression affect the progression of CAD. Cheng, F. et al. (Reference Cheng, Lin, Wang, Liu, Li, Yu and Gao2018) reported that lifestyle factors such as exercise, adherence to medication, and eating habits, were significant mediators of the relationship between Type D personality and plaque vulnerability (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Lin, Wang, Liu, Li, Yu and Gao2018). Moreover, a recent study found that AMI patients suffering from depression had a higher body mass index (BMI), less physical activity, and a higher likelihood of smoking when compared with patients who were not depressed (Nicholson, Morse, Lundgren, Vadiei, & Bhattacharjee, Reference Nicholson, Morse, Lundgren, Vadiei and Bhattacharjee2020). Most importantly, a previous study reported that the prevalence of non-adherence to medication was higher in PCI patients with a combination of Type D personality and depression when compared with other groups (Son, Lee, Morisky, & Kim, Reference Son, Lee, Morisky and Kim2018). Similarly, AMI patients with both Type D personality and depression had the lowest adherence rates to clopidogrel/ticagrelor during the follow-up period in this study. Additionally, Cox regression models showed that adherence to aspirin and clopidogrel/ticagrelor were protective factors against cardiovascular events. Therefore, the future study should analyze the mediation effect of medication adherence on the poor prognosis of patients with Type D personality and depression. Furthermore, biological mechanisms including increased pro-inflammatory activity, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction may affect the progression and prognosis of CAD in Type D personality or depression patients (Masafi et al., Reference Masafi, Saadat, Tehranchi, Olya, Heidari, Malihialzackerini and Rajabi2018). Therefore, patients with both Type D personality and depression need more attention and require more comprehensive interventions to improve their prognosis.

Accumulating evidence has suggested that sex has a differential influence on the impact of psychological distress on cardiac diseases (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Yu, Liu, He, Lv and Guo2020; Pimple et al., Reference Pimple, Lima, Hammadah, Wilmot, Ramadan, Levantsevych and Vaccarino2019). Similarly, this study revealed that the effect of Type D personality and depression on cardiovascular prognosis was more pronounced in men. The results obtained from the Cox regression model indicated that the Type D personality + depression and Type D personality + non-depression groups were associated with increased odds of MACEs and ISR in men, while only Type D personality + depression was associated with an increased risk of MACEs and ISR in women. Additionally, the recent largest prospective cohort study has reported that depression was associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiac mortality in Chinese adults, particularly in men (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Yu, Liu, He, Lv and Guo2020). Previous studies have reported that Type D personality males were characterized by the prominence of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysfunction (Riordan, Howard, & Gallagher, Reference Riordan, Howard and Gallagher2019) and endothelial dysfunction (Denollet et al., Reference Denollet, van Felius, Lodder, Mommersteeg, Goovaerts, Possemiers and Van Craenenbroeck2018) when faced with socially related sources of stress. These processes may be the potential mediators of the association between psychological factors and MACEs in males. Therefore, our results suggest that more attention should be paid to males with Type D personality during recovery from AMI, regardless of whether they are depressed or not. Moreover, providing psychological interventions to female patients with both Type D personality and depression would be beneficial.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths including the large sample size, prospective design, and the independent adjudication of outcomes. These factors enabled a rigorous investigation of the effects of Type D personality and depression on the prognosis of cardiac disease. In addition, the association between Type D personality, depression, and ISR made it possible to speculate the mechanisms through which the combined impact of Type D personality and depression led to adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

However, the study had a number of limitations. Firstly, it was a single-center study and thus the obtained results might not be sufficiently conclusive. Therefore, multi-center data are required for more comprehensive conclusions. Secondly, the psychological factors were measured based on self-report from patients. Thus, future studies should use psychology professionals in order to obtain more objective data. Thirdly, we did not conduct psychological evaluation during the follow-up. However, the baseline information also gave us strong information for the cardiovascular prognosis of patients suffering from AMI.

Conclusions

The findings obtained in this cohort study suggest that Type D personality, depression, and their combined effect can independently predict MACEs and ISR in AMI patients. In addition, Type D personality males were at a higher risk of MACEs and ISR, regardless of whether they were depressed or not. However, only a Type D personality combined with depression posed a higher risk of MACEs and ISR in women. Therefore, examining both Type D personality and depression may provide insights on the specific psychological phenotypes that pose the risk of adverse cardiovascular events. Furthermore, more effort is required to increase awareness and improve treatment strategies for the high-risk groups.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721002932

Author contributions

The manuscript was drafted by WY. All coauthors contributed to the design and management of this prospective cohort study. Moreover, all authors contributed to the critical review of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971015), National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1301101), and Humanity and Social Science Youth Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (19YJC190034).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients or the public had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.