Teaching about political conflict, particularly in faraway regions, requires an understanding of the perspectives and motivations of the parties to the conflict. This is especially true for classes on the Middle East and, specifically, the Arab–Israeli conflict, about which at least some American students may have “otherness” bias, predispositions brought from home, and resistance to opinions they do not share (Baylouny Reference Baylouny2009; Caplan et al. Reference Caplan, Pearlman, Sasley and Sucharov2012; Kirschner Reference Kirschner2012; Stover Reference Stover2005; Tétreault Reference Tétreault1996). Therefore, in our undergraduate class on the Arab–Israeli conflict at the University of Michigan, we strive not only for objectivity and balance in presenting factual information but also to foster an understanding of the narratives and points of view of the various parties to the conflict.

In a survey conducted in the first week of our class (Fall 2016), 73.9% of students reported having previous knowledge about the Arab–Israeli conflict. Furthermore, only 27.7% indicated that they were not predisposed to favor one side or the other. This also was the pattern when we previously taught the course. Therefore, an important goal has been to expose students to different viewpoints and, even more, to help them understand that these are not essentialist but rather the legitimate product of different lived experiences.

Various techniques have been used in classes that address competing viewpoints. Some researchers argue that “active learning” increases not only student knowledge but also engagement, teamwork skills, and receptivity to multiple perspectives (Brock and Cameron Reference Brock and Cameron1999). These techniques include, among others, simulations of real-world or fictional scenarios (Asal and Kratoville Reference Asal and Kratoville2013; Baranowski and Weir Reference Baranowski and Weir2015; Dougherty Reference Dougherty2003; Wedig Reference Wedig2010); role-playing (Baylouny Reference Baylouny2009; Powner and Allendoerfer Reference Powner and Allendoerfer2008; Williams Reference Williams2006); structured in-class debates (Dougherty Reference Dougherty2003; Omelicheva Reference Omelicheva2006); and case-based exercises (Krain Reference Krain2010).

These methods are valuable but they often require intensive preparation, significant class time, and classes of a certain size—any of which may preclude their use in some settings (Baranowski Reference Baranowski2006). In this article, we argue and find empirical evidence that a simple, short-essay assignment, which can be applied easily and repeatedly in any class type and size, has a clear impact on students’ understanding of different perspectives in the Arab–Israeli conflict and their willingness to see these perspectives as legitimate. Specifically, we randomly pre-assign students to either justify or criticize a controversial decision at a key historical moment—in this case, Arab and Palestinian rejection of the United Nations (UN) partition resolution of 1947, which led to war and the Arabs’ defeat—followed by group discussion and a short reflective essay.

In this article, we argue and find empirical evidence that a simple, short-essay assignment, which can be applied easily and repeatedly in any class type and size, has a clear impact on students’ understanding of different perspectives in the Arab–Israeli conflict and their willingness to see these perspectives as legitimate.

Exploiting the essay’s random assignment, we found quantitative evidence that Israel-supporting students who were asked to justify the Arab rejection in 1947 moderated their judgments of the Palestinians more than students assigned to criticize the decision. In addition, we analyzed students’ written reflections on the exercise and found that this assignment also contributed to deeper understanding. We asked students to justify or criticize an Arab decision at an important historical moment; however, a similar exercise focused on Israeli actions should be used to promote a fuller understanding of both sides in the conflict.

THE ASSIGNMENT

Our class on the Arab–Israeli conflict at the University of Michigan, taught in Fall 2016, had 72 undergraduate students, 87% of whom were juniors and seniors mostly majoring in political science or international studies. The course had two primary goals. First, it sought to provide an in-depth overview of the historical facts and political dynamics that have marked the conflict from the early history of both peoples until the present time. Associated with this objective were a heavy reading load, weekly quizzes, and three exams, which left little time for exercises spanning multiple class sessions. Second, the course especially emphasized familiarity with and appreciation of the narratives and perspectives of early Zionists and Israelis and of Palestinians and other Arabs. Accordingly, we assigned books written from one or both perspectives.Footnote 1 The course also drew on the personal experience of the instructors, who attended university and lived for extended periods in Israel and the Arab world. There were also weekly small-group discussions led by a graduate-student instructor.

The weekly quizzes focused on factual knowledge as did the three exams. In addition, the exams also asked students to indicate and then justify their agreement or disagreement with competing arguments associated with a controversial or contested issue. The goal of the assignment discussed in this article was to deepen student understanding of the parties to the conflict, particularly the logic and reasoning behind their actions during important moments. The assignment described and evaluated herein centers on a watershed moment: the Arab and Palestinian rejection of the UN partition plan of 1947. The UN proposal to divide the land of Palestine into two states was accepted by the Zionists but was rejected by the Arabs. This resulted in a war that ended with an Arab defeat and the establishment of Israel.

Our assignment asked students to write a one-page essay that discusses facts and reasons that either justify or criticize the Arabs’ rejection of the UN partition plan.Footnote 2 To avoid the influence of predispositions, students were randomly assigned to one of the two positions so that their assignment was to either justify or criticize the Arab rejection. Thus, with their conclusion preset, the main task for students was to find and articulate sufficiently strong arguments in support of that conclusion. A one-page essay was sufficient for this purpose because only a summary of the arguments that they found to be persuasive was required. Nevertheless, depending on the structure of the class and the instructor’s goals and resources, a longer essay that probed and engaged student understanding in greater depth also would be appropriate.

The assignment included two additional components. First, following submission of the essays, we held a discussion section in which students in groups of three or four compared their arguments, together selected those that they considered the strongest, and then shared their conclusions in open discussion with participants of six or seven other groups. This discussion proved to be particularly rich, thoughtful, and lively.

Second, following the group discussion, students submitted a short (usually a half-page) written reflection in which they were asked to indicate whether they agreed with the position to which they had been assigned and whether their views had changed as a result of the exercise. This enabled them to engage in meta-learning—that is, to reflect not only on their views about the Arabs’ 1947 decision but also on the information and reasoning that shaped their views and those of others.

Random assignment of essay positions was necessary to ensure that students who criticized and students who justified the Arabs’ 1947 decision were comparable with respect to prior knowledge and predisposition regarding the conflict. Moreover, random assignment enabled group discussions among students who approached the same position with different predispositions. Nevertheless, instructors who want to maximize the essay’s effect on students who either justify or criticize a position with which they disagree can pre-assign them to positions that contradict their predispositions and use random assignment only for those whose predispositions are neutral.Footnote 3

The survey asked three general questions: which side has claims that are more just (justice); which side bears more responsibility for failure to resolve the conflict (blame); and for which side does the student have more empathy (empathy).

EVALUATION OF THE ASSIGNMENT ’S ESSAY COMPONENT

During the first week of class, we distributed a survey that asked students about their knowledge and opinions pertaining to the conflict.Footnote 4 The survey asked three general questions: which side has claims that are more just (justice); which side bears more responsibility for failure to resolve the conflict (blame); and for which side does the student have more empathy (empathy).Footnote 5 For each question, we subsequently assigned a score of -1 for an answer in support of the Israelis, 1 for an answer in support of the Palestinians, and 0 for a neutral position. We then summed the three questions to create a 7-point scale of Israeli–Palestinian favorability, with each student receiving a score that ranged from -3 to 3.

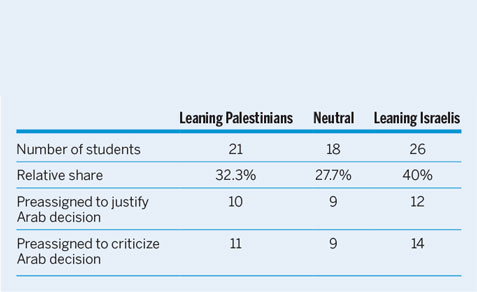

We used this scale to code each student’s predispositions toward the conflict. Then, as shown in table 1, we ensured that an approximately equal number of pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian students were randomly assigned to each of the two essay positions regarding the Arabs’ 1947 decision. Finally, after the essays were submitted but before group discussion, we distributed a survey identical to the one given in the first week of class and again calculated an Israeli–Palestinian favorability score. This design allowed us to evaluate the effect of writing an essay separately from that of the subsequent small-group discussion.

Table 1 Distribution of Students’ Predispositions and Essay Preassignment

To begin, we compared responses to the first-week and the post-essay surveys among students randomly preassigned to justify Arab rejection of the UN partition plan and those randomly preassigned to criticize it. Figure 1 presents a t-test comparing the difference in means within each preassigned group. The figure shows that there is no significant change in the post-essay scores of students assigned to criticize the Arab rejection, but there is a statistically significant increase in Palestinian favorability among students assigned to justify the rejection. The between-group difference in effect is significant at a 93% confidence level.

Figure1 T-Test of Difference in Means Before and After Essay

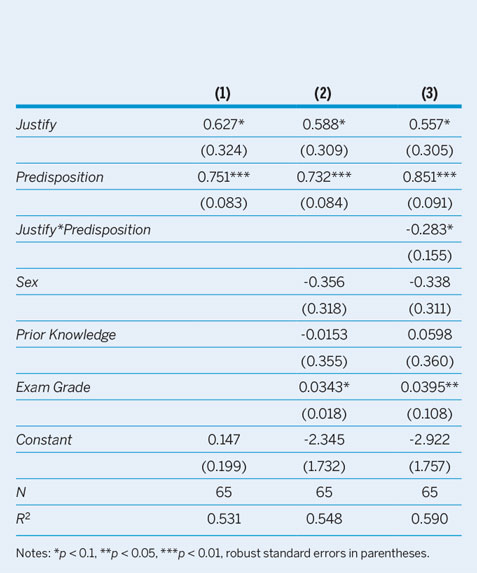

Could this effect be driven by other factors? To address this concern, we estimated a multivariate OLS regression of post-essay Palestinian favorability scores on our main explanatory variable, being preassigned to justify the Arab rejection (justify). We also controlled for week 1 predisposition scores (see table 2, model 1) and for sex, self-reported prior knowledge, and grade on an exam taken two weeks before the essay assignment (see table 2, model 2). Not surprisingly, initial predisposition is the strongest predictor of post-essay position; nevertheless, being preassigned to justify the 1947 Arab rejection had a positive, statistically significant effect on post-essay Palestinian favorability scores. Higher performance on the exam, which may reflect stronger command of the material leading up to the essay, also had a significant positive effect on post-essay Palestinian favorability, although small in size.Footnote 6

Table 2 OLS Regression of Post-Essay Position

Notes: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01, robust standard errors in parentheses.

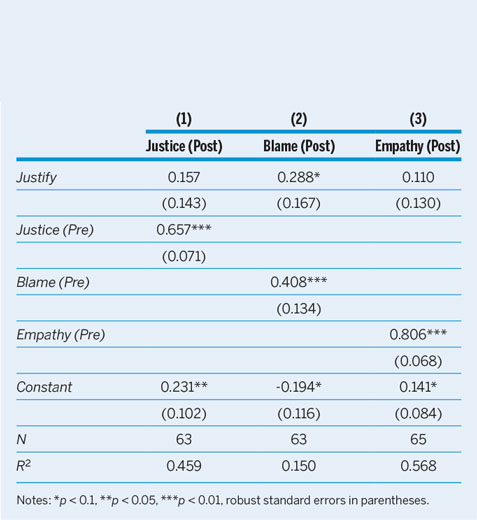

As emphasized in an introductory lecture on the first day of class, our purpose was to help students understand all actors better, not to convince them to favor one side over the other. This raises the question of what drives the increased Palestinian favorability among students assigned to justify the 1947 decision. To examine this question, we ran the same regression separately for each of the three favorability-score components. The results, shown in table 3, suggest that justifying the Arab decision had a statistically significant effect on blame attribution but not on justice of claims or student empathy (although each of the latter two also had a positive sign). Furthermore, the estimated effect on blame attribution was double the size of the other two components. In other words, justifying the Arab rejection in 1947 does not necessarily convince students that the Palestinians have more just claims than the Israelis; neither did it increase empathy for the Palestinians. However, it did seem to lessen the blame that students attribute to Palestinians for failure to resolve the conflict. This indicated increased understanding of the Arabs’ decision, even if students believed Arab and Palestinian actions were wrong.

Table 3 OLS Regression of Post-Essay Position by Component

Notes: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01, robust standard errors in parentheses.

Finally, are all students equally likely to change their judgment of the conflict after justifying the Arab rejection? To answer this question, we interacted justification with predisposition (see table 2, model 3). Figure 2 plots the marginal effect of justification on post-essay scores under different levels of predisposition. The y-axis shows the added effect that justifying (compared to criticizing) was predicted to have on students’ post-essay Palestinian-favorability scores. The result was not uniform: Israel-supporting and neutral students who defended the rejection were less critical of the Palestinians after the essay, but students who favored the Palestinians did not change their support regardless of their preassigned position. For example, students who had a score of -3 in the first week—the maximum support of Israel—and justified the 1947 Arab rejection were predicted to change their score by 1.4 points more than similarly pro-Israel students who criticized the Arab decision, all else being equal. Meanwhile, students who were predisposed to favor the Palestinians did not see a statistically significant change in their scores, regardless of their essay position.

Figure 2 Marginal Effect of Justification on Post-Essay Position under Different Levels of Predisposition (with 90% Confidence Intervals)

The assignment’s focus is on Arab and Palestinian actions; Israeli actions were not considered in this exercise. Thus, students favoring the Palestinians did not debate or increase their understanding of Israelis. With respect to the Palestinians, the takeaway appears to be that understanding the actions of an actor that is not favored increases after being forced to view the situation from the perspective and position of that actor. Criticizing the actions of a favored actor, by contrast, does not seem to have any significant effect. In the case of our particular course, it would be instructive to add an analogous exercise that focuses on a controversial Israeli action at a key historical moment. This would enable us to determine whether the results are comparable and, if so, to increase student understanding of Israeli as well as Palestinian actions.

EVALUATION OF GROUP DISCUSSIONS AND STUDENT REFLECTIONS

The small-group discussions also contributed by giving students an opportunity to deliberate, compare arguments, and reconsider their positions. Contrary to the quantitative analysis used to assess the essay component, however, the effect of group discussions was diverse and better evaluated qualitatively. We therefore analyzed the contribution of the group discussions using the students’ written reflections submitted at the end of the exercise.

Passive learning and exclusive focus on historical facts and concepts are not enough to increase student understanding of the multiple narratives and dynamics that characterize international-conflict situations.

The contribution of group discussion is reflected in several areas. Some students changed their mind after hearing counterarguments from their peers. For example, one student noted, “I remember in discussion one of my peers invoking the concept of realpolitik when considering what should have been done, and I feel that this is the most logical way to think about the situation.” A different student attested, “In my essay, I strongly believed that the UN was an objective body…. However, our discussion made me question the objectivity of the UN that I had so heavily believed in.”

For other students, group discussion reinforced initial opinions. Some felt empowered after hearing other students voice arguments similar to their own. For example, one student wrote, “Discussion definitely solidified my initial opinion that the Palestinians [and Arabs] were justified in rejecting the UN Partition Plan, as my fellow classmates echoed all the arguments I presented.” Other students reinforced their opinions by hearing arguments they had not previously considered. As one student noted, “In our discussion, many new, interesting points were brought up that not only built upon my argument but expanded it into other realms I hadn’t considered in my essay.” It is interesting that the refutation of weak counterarguments made by their peers also provided reinforcement. One student explained, “The points made by the opposite position are not particularly convincing…[and] I believe my own argument may have been even further strengthened by engaging more with the opposing side.”

Finally, some students developed more nuanced positions that considered both sides. One student reflected, “I really valued the in-group discussion. It really made me think, and I felt that I was consistently changing my mind based on what people were saying. It is clearly a very complex issue and there seem to be very strong arguments on both sides.” Another added, “My opinion overall was not affected through this exercise, as I still believe each side acts in their own self-interests, but the way in which I think about the decisions each side makes did change.”

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Passive learning and exclusive focus on historical facts and concepts are not enough to increase student understanding of the multiple narratives and dynamics that characterize international-conflict situations. This is of particular concern when teaching about conflicts for which many students may have strong predispositions, which typically is the case in courses on the Arab–Israeli conflict. Various active-learning techniques address this problem but often at a cost of long preparation and substantial class time. There also may be constraints imposed by class size and requirements. This article provides evidence that a short essay asking students to defend a key action taken by one of the actors makes them more understanding and less accusatory of that side—even as it does not change their initial attitude toward the parties to the conflict. Adding a small-group discussion and a written reflection further helps students make more informed and reasoned judgments.

The short-essay assignment we describe is not a substitute for richer active-learning methods, some of which have added value that a simple essay cannot achieve. Rather, our exercise borrows elements from existing methods—role playing, non-cooperative simulations, and case-based exercises—and, in this way, expands the current menu of activities available for political science teachers. Importantly, our assignment rests on the far end of a complexity spectrum of active-learning methods, providing an exercise that is easy to write and grade; can be used multiple times during a semester; fits any class size and topic; and does not come at the expense of other more traditional assignments such as exams, quizzes, and research papers. Furthermore, our suggested exercise is flexible and can be easily modified to include additional point of views, longer essays, and more or fewer group activities.

Finally, we provide a rigorous empirical evaluation of our exercise’s effectiveness. In recent years, there have been increased efforts to evaluate active-learning methods, yet they focus mostly on improvement in student learning, such as the command of facts and class performance (Alberda Reference Alberda2016; Baranowski Reference Baranowski2006; Powner and Allendoerfer Reference Powner and Allendoerfer2008). Although some studies also evaluate the effect on student understanding of multiple perspectives, they typically use only qualitative techniques, such as content analysis and subjective student feedback (Baylouny Reference Baylouny2009; Dougherty Reference Dougherty2003; Williams Reference Williams2006; but see Stover Reference Stover2006). We hope this article encourages others to use multiple and more rigorous methods when evaluating pedagogical tools for increasing student understanding of diverse points of view.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909651700230X

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Mika LaVaque-Manty, Lior Sheffer, two anonymous reviewers, and the editor for their insightful comments and suggestions. Any errors remain our own.