Over 1.4 million of America’s most vulnerable citizens reside in 15,700 long-term care facilities.Reference Harris-Kojetin, Sengupta and Park-Lee 1 These facilities and their residents are especially susceptible to disruptions associated with natural disasters.Reference Dosa, Hyer and Brown 2 Of the 877 fatalities attributed to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, 103 (12%) occurred in nursing home residents.Reference Brunkard, Namulanda and Ratard 3 Long-term care facilities often have limited experience and resources for disaster planning and response.Reference Dosa, Hyer and Brown 2 , Reference Banks 4

A number of authors have surveyed administrative and clinical staff after their long-term care facility experienced a hurricane or earthquake.Reference Carpender, Campbell and Quiram 5 - Reference Mangum, Kosberg and McDonald 15 These surveys found several common themes associated with transportation, staffing problems, and facility issues. Frequently experienced transportation issues included failure of contracted vendors to provide service, buses or airplanes not adequately equipped to handle stretchers and wheelchairs, long and difficult trips that were medically and emotionally deleterious, traffic delays, and difficulties dealing with demented residents on buses. Reported staffing issues included staff members being unwilling or unable to evacuate, family support issues such as child care and pet care, and shortages of licensed personnel to care for residents. When long-term care facilities sheltered in place, reported facility issues included inadequate power and water, loss of communications, and inadequate supplies including pharmaceuticals. Additionally, surveys of long-term care facilities receiving evacuees from other facilities also reported challenges including inadequate supplies and medications, insufficient medical information about evacuees, and difficulty maintaining adequate staffing.Reference Laditka, Laditka and Xirasagar 9 , Reference Cefalu 14

Following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General (OIG) commissioned a study of preparedness and response of Medicare- and Medicaid-certified nursing homes. The resulting report, issued in 2006, 12 illustrated that although most nursing homes in the United States met federal standards for emergency plans and training, many experienced logistical problems and poor outcomes during disasters, did not always follow emergency plans, and lacked coordination with state and local emergency management agencies. The problems occurred regardless of whether a nursing home evacuated or sheltered in place. The 2006 report included recommendations for strengthened federal standards that better reflected expert recommendations and improved collaboration between nursing homes and emergency management agencies. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) responded to this report with the development of specific guidance and checklists for health care facilities. A follow up OIG study covering the period of 2007-2010 was published in 2012. 13 It noted persistence of preparedness gaps in nursing homes and identified lack of completion of preparedness tasks related to a number of issues. The latter included staffing; resident care; resident identification, resident tracking, and maintaining resident information; sheltering-in-place; evacuation; and communication and collaboration. Recommendations in the second OIG study included further revisions of CMS regulations, additional training for CMS surveyors on evaluation of emergency plans, and development of effective models for disaster assistance by state and local long-term care ombudsmen.

After Hurricane Sandy in October 2012, the National Long-Term Care Ombudsman Resource Center surveyed state and local long-term care ombudsman programs and concluded that there was lack of long-term care ombudsman program involvement in emergency management planning and activities and minimal communication between long-term care ombudsmen and long-term care facilities about emergency planning. 16 In 2013, CMS revised its Emergency Preparedness Checklist for Long-Term Care Facilities. 17 These revisions incorporated a “whole community” approach to emergency preparedness, emphasizing coordination of emergency planning and response on a community level, including how long-term care facilities might serve other health care facilities and the community at large. 18 Specific recommendations on the revised checklist included incorporating an all-hazards approach to written emergency plans, coordinating with local emergency management agencies and health care coalitions, participating in community exercises, and coordinating planning and response with long-term care ombudsman programs.

These federal agency reports were insightful and useful for policy but did not specifically address whether interventions or characteristics of facilities or disasters affect disaster outcomes for residents, staff, or facilities, and if so, by what mechanism. In an attempt to study these questions, we reviewed published literature regarding disaster characteristics, facility characteristics, patient characteristics, and interventions that affected outcomes in long-term care facilities that experienced or prepared for a disaster.

METHODS

Inclusion Criteria

We included articles published from 1974 through September 30, 2015. We chose to begin our review in 1974 because that was the year Congress passed the Disaster Relief Act (PL 93-288), which described the statutory authority for most federal disaster response activities. We included articles that met all of the following criteria: (1) written in English; AND (2) reported data or descriptive information about long-term care facilities that experienced or prepared for a disaster; AND (3) described disaster characteristics, facility characteristics, patient characteristics OR an intervention; AND (4) studied an outcome.

Definitions

For the purposes of this review, we considered a disaster a “catastrophic incident” as defined by the National Response Framework: 19 “A catastrophic incident is defined as any natural or manmade incident, including terrorism, that results in extraordinary levels of mass casualties, damage, or disruption severely affecting the population, infrastructure, environment, economy, national morale, or government functions.” Common catastrophic incidents include floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, and wildfires. Disaster characteristics included disaster type or severity, such as hurricane category. We also included articles that studied preparedness and response to pandemics that might affect the entire population (eg, pandemic influenza) but excluded articles that dealt only with incidents that were internal to the facility, such as internal infectious disease outbreaks, internal food-borne infections, and structural fires. We defined interventions as actions or activities to mitigate against, prepare for, respond to, or recover from a catastrophic incident. We included articles that studied outcomes that applied to residents (eg, morbidity, mortality, psychological well-being), staff (eg, safety, psychological well-being, perceived readiness), or facilities (eg, structural integrity, costs, regulatory compliance). In our definition of long-term care facilities, we included nursing homes, skilled nursing facilities, and inpatient rehabilitation centers; we excluded assisted-living centers and personal care homes.

Search Strategy

We searched several databases including PubMed Medline, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, PsycINFO, and CINAHL Complete (EBSCOhost) and Web Of Science. Incorporating both key word and subject headings in our search strategies, various terms related to “residential facilities,” “nursing homes,” or “long-term care” were combined with terms associated with “disasters” or “emergencies” as well as terms that would specify “management,” “preparedness,” or “recovery.” We limited our search to English-language articles. In addition, we reviewed the reference lists of included articles to further identify relevant articles. The specific search strategies for each database are available from the primary author upon request.

Source Selection

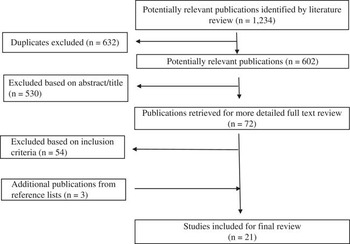

As illustrated in Figure 1, the initial search strategy returned 602 nonduplicated potential sources to include in this review. Two independent reviewers read abstracts or online versions of these sources to identify obvious news items, opinion pieces, reports of individual experiences, and articles that obviously did not fit the inclusion criteria. When both reviewers agreed, these sources were eliminated from further review. This initial examination eliminated 530 works. Two authors then independently reviewed the remaining 72 articles in detail to ascertain that they met all inclusion criteria. When there were disagreements, the reviewers discussed the publication in detail until they reached consensus. Eighteen articles remained for inclusion in this review. One additional publication and 2 government reports were identified from reference lists or other sources; thus, 21 publications were included in the final review. Two reviewers evaluated each article with attention to methodology, results, and authors’ discussion of implications.

Figure 1 Flow Chart of Selection of Sources.

RESULTS

All of the included articles fell into one of the following categories: those pertaining to facility or disaster characteristics that predicted preparedness or response, those pertaining to interventions to improve preparedness, and those describing health effects of disaster response, most often related to facility evacuation. We included articles that reported outcomes in facilities that had experienced one or more disasters. Because all of the articles described observational studies and the studies were heterogeneous, we performed a narrative literature review.

Facility and Disaster Characteristics Predicting Preparedness or Response

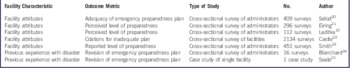

Seven studies examined facility characteristics that predicted preparedness for or response to a disaster (Table 1). Five of these 7 examined the relationship between facility attributes and preparedness. Two of these 7 examined the effects of previous experience with a disaster on facility preparedness planning. In addition to the 7 articles that examined facility attributes, an additional 2 articles reported on disaster characteristics that affected response.

Table 1 Studies That Examined Facility Attributes or Interventions Predicting Improved Preparedness or Response

Selod et alReference Selod, Heineman and O’Brien 20 reviewed surveys from 409 of 770 nursing home administrative staff attending a 2010 workshop for facilities participating in the federally funded Disaster and Emergency Preparedness Planning for Long-Term Care Facilities (PREPARE) educational program. Compared with facilities that were part of a continuing care retirement community, stand-alone skilled nursing facilities were more likely to have a disaster plan that specifically stated whom to contact at the state level in an emergency (63.9% vs 36.1%, P<0.05) and to have a disaster plan that included a patient tracking system (61.1% vs 38.9%, P<0.05). Compared with urban and suburban facilities, rural nursing homes were more likely to have a written agreement for the provision of emergency shelter (51.5% vs 22.3 % vs 26.2%, P<0.05) and to have participated in emergency preparedness training (51.9% vs 22.8% vs 25.3%, P<0.05). Compared with independent nursing homes, nursing homes that were part of a chain were more likely to have provided a copy of the disaster plan to local emergency management (65.8% vs 34.2%, P=0.004).

Eiring et alReference Eiring, Blake and Howard 21 reviewed surveys completed in 2010 by 296 of 498 administrators of nursing homes in Georgia, California, and Florida that were chosen on the basis of vulnerability to disasters. The authors found that a multivariate analysis failed to identify any relationship between nursing home attributes (number of residents, hospital-affiliated, chain-affiliated, for-profit status, and previous citation) and 5 measures of preparedness (more than 3 disaster drills/year, discussion of preparedness with families, ability to shelter-in-place for more than 3 days, food and water supply for more than 3 days). Compared with Georgia, a higher proportion of facilities in California and Florida reported that they were able to shelter-in-place for more than 6 days.

Laditka et alReference Laditka, Laditka and Xirasagar 10 reviewed surveys from 112 of 192 South Carolina long-term care facility administrators in July 2005, and 50 of 112 of the same facilities 2 weeks after Hurricane Katrina in September 2005. The authors found that there was no difference in the administrators’ perceived level of preparedness between rural and urban nursing homes and between those in coastal areas versus those in inland areas.

CastleReference Castle 22 examined evacuation plans of 2134 of 4000 randomly selected US nursing homes in 2006 and assessed their compliance with criteria developed by an expert panel funded by the OIG. The author also reviewed deficiency citations for inadequate plans that were included in the Medicare and Medicaid Online Survey, Certification, and Recording (OSCAR) database from 1997 to 2005; this database includes information for 121,779 US nursing homes. The author found that for-profit status, large number of beds, and higher average Medicaid occupancy were facility attributes significantly associated with a greater likelihood of receiving a citation for an inadequately written emergency or evacuation plan, with adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals [CIs]) of 1.22 (1.09-1.36), 1.06 (1.00–1.13), and 1.04 (1.02–1.07), respectfully.

Smith et alReference Smith, Shostrom and Smith 23 reviewed surveys completed in June 2007 by administrators of 451 of 656 Michigan and Nebraska nursing homes with regard to preparedness for pandemic influenza. With a few exceptions, nursing homes in the 2 states did not differ in their levels of self-reported pandemic planning. Nursing homes in Nebraska were more likely to have provided staff education about pandemic influenza. Nursing homes in Michigan were more likely to have stockpiled supplies, to have mental health services available, and to have undertaken some other planning activities. Results from rural versus urban nursing homes were not compared in their study. These authors did not hypothesize about the reasons for these differences between the states but felt that they were probably not significant.

Two studies in this category examined the effects of previous experience with a disaster on facility preparedness planning. Blanchard and DosaReference Blanchard and Dosa 24 surveyed 20 of 51 Louisiana nursing home administrators after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and after Hurricane Gustav in 2008. Sixteen of 20 administrators experienced both hurricanes. The investigators inquired about the administrators’ sense of preparedness, resident morbidity, logistical problems, collaboration with officials, and transportation effectiveness. Although only 9 of 20 respondents evacuated for Katrina, 16 of 16 respondents had evacuated for Hurricane Gustav. Overall, nursing home administrators rated improved confidence in preparedness for Gustav (8.3 vs 5.6 on a 10-point Likert scale). Compared with response during Hurricane Katrina, 73% reported improved collaboration with state emergency management and 55% noted improved transportation during Hurricane Gustav. SealeReference Seale 25 reported on changes in preparedness planning by an inpatient rehabilitation center in Texas that occurred between facility evacuations for Hurricane Rita in 2005 and Hurricane Ike in 2008. After Hurricane Rita, this facility extensively revised its plan to identify a primary evacuation site, develop pre-evacuation action protocols, develop specific plans for administrative authority, and develop criteria for evacuating the facility. This facility also conducted several exercises; developed a telephone and web-based messaging system; purchased a utility trailer to transport food, clothing, medical records, and equipment; and mapped a specific evacuation route with pre-identified locations for fuel, food, and medical care.

Two studies examined the effect of disaster characteristics on response outcomes. The OIG 13 reviewed disasters in the United States occurring between 2007 and 2010 and found that facilities were more likely to evacuate rather than shelter-in-place for hurricanes compared to other types of disasters (Table S1 in the online data supplement). The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) conducted an extensive investigation 26 following the 2011 Joplin, Missouri, tornado that resulted in 161 deaths, including 21 deaths in 2 nursing homes. The NIST concluded that the degree of structural damage and subsequent injury and mortality was not associated with facility age of construction but was associated with wind speeds impacting facilities.

Interventions Designed to Improve Preparedness

Four studies examined interventions designed to improve preparedness for a disaster (Table 2). Brown et alReference Brown, Bruce and Hyer 27 administered psychological first aid training to 22 nursing home providers, all of whom reported that after the training, they had increased knowledge of disaster-related psychological distress and increased confidence in providing psychological first aid to residents after disaster.

Table 2 Studies That Examined Interventions Designed to Improve Preparedness

O’Brien et alReference O’Brien, Selod and Lamb 28 reviewed the effects of a national Bioterrorism and Emergency Preparedness and Aging train-the-trainer curriculum (PREPARE: Disaster and Emergency Preparedness Training for the Long-Term Care Workforce), conducted in 2006 and 2007. Surveys of 1227 graduates of this training program indicated that the quality of their organizations’ preparedness plans had increased after receiving this training. This included a 24.2% increase in including the local public health department in their facility plans, a 27.8% increase in including local emergency management in their facility plans, a 24.1% increase in providers including the local Red Cross office in their plans, and a 26.3% increase in plans that included procedures for post-incident debriefing and counseling for residents and staff.

Covan and Fugate-WhitlockReference Covan and Fugate-Whitlock 29 supplied gerontology graduate students and a planning template to 24 nursing home administrators in North Carolina in 2006 in an attempt to develop plans that would be submitted to local emergency management for review. The number of plans received by local emergency management did not increase after this intervention.

The OIG selected 24 Medicare- and Medicaid-certified nursing homes whose residents sheltered in place or were evacuated in response to floods, hurricanes, or wildfires from 2007 to 2010, conducted detailed telephone and on-site interviews, and reviewed these facilities’ emergency preparedness plans. 13 The report stated that 17 of 24 nursing homes experienced significant challenges with disaster response. The authors of this report stated that of the nursing homes reporting significant challenges, only 29% (5/17) had their plans reviewed by local emergency management, only 12% (2/17) had participated in community-wide preparedness meetings, and none (0/17) had participated in local disaster drills. The authors of these reports did not provide comparative data for the facilities not reporting significant challenges.

Health Effects of Disaster Response

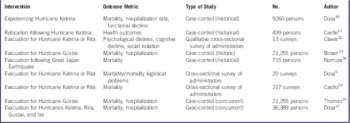

Nine studies examined the health effects of disaster response, primarily related to evacuation (Table 3). With one exception, these studies evaluated the effects of response to hurricanes. Five of these compared health outcomes of nursing home residents in facilities that experienced a disaster compared with a control cohort of patients in facilities that did not experience a disaster.Reference Dosa, Feng and Hyer 30 - Reference Nomura, Gilmour and Tsubokura 34

Table 3 Studies That Examined Health Effects of Interventions During Response

Dosa et alReference Dosa, Feng and Hyer 30 studied 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality, hospitalization rates, and measurements of functional decline for 9260 residents from 141 long-term care facilities in Louisiana and Mississippi that were impacted by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and then compared the data with data for residents residing in the same facility during the 2 prior nonhurricane years (see Table S2 in the online data supplement). Many of these facilities evacuated. After Hurricane Katrina, mortality rate, hospitalization rate, and functional decline all increased.

Castle and EngbergReference Castle and Engberg 31 studied the health outcomes of 439 residents from 12 nursing homes that were closed following Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and compared these with the health outcomes of matched urban nursing home residents elsewhere in the South prior to Hurricane Katrina. Compared with matched controls, relocated residents were more likely to have died or developed a pressure ulcer and were less likely to have experienced restraint use within 4 months of evacuation (adjusted odds ratios: 1.85, 1.99, and 0.50, respectively).

Claver et alReference Claver, Dobalian and Fickel 32 used a qualitative case study design to formally interview 13 administrative and clinical staff at 4 Veterans Health Administration nursing homes who evacuated residents during Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005. Eight of the 13 respondents reported that many residents exhibited severe symptoms of psychological stress or cognitive decline and that this persisted after the immediate evacuation was over. This stress was felt to be related to difficulty locating family or lack of a social support network.

Brown et alReference Brown, Dosa and Thomas 33 examined 30-day and 90-day mortality rates for 21,255 residents of 119 Louisiana and Texas nursing homes that evacuated in 2008 for Hurricane Gustav and compared these to a control population from the same nursing homes during the same time period in the 2 previous nonhurricane years. Relative to prior years, among the evacuation cohort, there was a 2.8% increase in death at 30 days and a 3.9% increase in death at 90 days, controlling for resident demographics and acuity.

Nomura et alReference Nomura, Gilmour and Tsubokura 34 examined mortality risk for nursing home residents before and after the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami of 2011 that resulted in a nuclear power accident. Five nursing homes with 715 residents located within a 20-km compulsory evacuation zone were evacuated to another facility. A number of residents were relocated more than once. Compared to the 5 years before the earthquake, during the 250-day period after the earthquake, evacuated residents showed a mortality risk of 2.68 (95% CI: 2.04–3.49). There was substantial variation in mortality risk between facilities that was not related to evacuation distance, which suggests that facility-specific factors may have affected mortality. For residents with more than one relocation, mortality was higher with the first evacuation than for subsequent relocations.

Four studies compared outcomes in nursing home evacuees and nursing home residents who sheltered in place for the same hurricane. Dosa et alReference Dosa, Grossman, Wetle and Mor 6 surveyed and interviewed 20 nursing home administrators whose facilities had experienced Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005. Compared to sheltering-in-place, evacuation was reported to be associated with more resident morbidity and mortality (40% vs 9%) and more logistical problems. Similarly, Castro et alReference Castro, Persson and Bergstrom 35 analyzed surveys of 217 of 520 administrative personnel of nursing homes and assisted-living facilities in a 13-county area in Texas impacted by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Of the 65 surveyed nursing homes in this study, 35 (54%) evacuated a total of 2800 residents (average of 80 residents per evacuated facility). The only resident deaths occurred in facilities that evacuated, with 14% of evacuating nursing homes reporting a resident death. Thomas et alReference Thomas, Dosa and Hyer 36 compared 30-day and 90-day mortality and hospitalization rates for functionally impaired residents who evacuated in 2008 for Hurricane Gustav (a relatively weak hurricane) compared with similar residents who did not evacuate. Evacuation was associated with 8% more hospitalizations but was not significantly related to mortality. Finally, Dosa et alReference Dosa, Hyer and Thomas 37 examined the effects of evacuation compared with sheltering-in-place on morbidity and mortality for nursing home residents in facilities experiencing any of 4 hurricanes (Katrina and Rita in 2005, Gustav and Ike in 2008). Compared with historical control periods, 30-day and 90-day mortality of residents increased after each of these 4 storms. Using an instrumental variable analysis, these authors demonstrated that compared with sheltering-in-place, evacuation further increased the probability of death at 90 days from between 2.7% and 5.3% and hospitalization rate at 90 days from between 1.8% and 8.3%. This analysis found that certain storms had a more deleterious effect on resident health, but that individuals who were evacuated experienced worse outcomes. Hurricane Katrina (the strongest of these hurricanes) was associated with the highest increase in mortality, but even for Katrina, residents of facilities that evacuated had a greater mortality rate than did residents of facilities that sheltered in place.

Levels of Evidence

Using the National Health and Research Medical Council hierarchy 38 (Table S3 in the online data supplement), articles studying facility characteristics that predicted preparedness or response, as well as all of the studies examining interventions designed to improve preparedness, provided level IV evidence (cross-sectional surveys). Three of the articlesReference Dosa, Grossman, Wetle and Mor 6 , Reference Claver, Dobalian and Fickel 32 , Reference Castro, Persson and Bergstrom 35 that examined health effects of interventions during response were cross-sectional surveys and thus also constituted level IV evidence. Six of the studies that examined health effects of interventions during responseReference Dosa, Feng and Hyer 30 , Reference Castle and Engberg 31 , Reference Brown, Dosa and Thomas 33 , Reference Nomura, Gilmour and Tsubokura 34 , Reference Thomas, Dosa and Hyer 36 , Reference Dosa, Hyer and Thomas 37 were case-control studies with historic (Level III-3) or concurrent controls (Level III-2). We judged these studies to have consistent findings and as having low risk for bias. We found no articles describing studies with level II or III-1 evidence (prospective cohort studies, randomized controlled trials, or pseudo-randomized controlled trials). Given the complexities and ethical considerations of conducting randomized trials in disaster preparedness, the level III evidence that is available in some studies is likely the best that can be expected in this area of study.

DISCUSSION

Although much has been written about the difficulties facing long-term care facilities that experience a disaster, we found a relative paucity of articles that have studied characteristics or interventions that affected outcomes. Although there were a number of studies related to the 2005 Hurricanes Rita and Katrina, we found no articles summarizing interventions affecting long-term care resident or facility outcomes following Hurricane Sandy in 2012. In general, the available articles described studies that were limited in scope and observational in design, and thus recommendations based on the evidence must be made with caution. Nonetheless, we believe that the evidence-based literature supports 6 specific recommendations (Table 4).

Table 4 Authors’ Evidence-Based Recommendations

The studies that looked at facility attributes predicting preparedness were inconsistent in their findings. Eiring et alReference Eiring, Blake and Howard 21 failed to find any attributes that predicted 5 measures of preparedness; Laditka et alReference Laditka, Laditka and Xirasagar 10 did not find any differences in preparedness between rural and urban nursing homes or between nursing homes located in coastal areas versus inland areas. Three other studies 17 , 19 , Reference Selod, Heineman and O’Brien 20 did not find consistent facility attributes predicting preparedness. These studies were heterogeneous in their definition of preparedness and were not consistent in the facility attributes studied. Two studiesReference Blanchard and Dosa 24 , Reference Seale 25 with level IV evidence (one cross-sectional survey and one case study) were consistent in finding that a facility’s previous experience with a disaster improved preparedness. We thus conclude that the current evidence-based literature suggests that one cannot make accurate predictions about nursing home preparedness on the basis of facility attributes, with the exception that previous experience with a disaster may improve preparedness. In our opinion, the policy implication of this finding is that emergency management and other governmental agencies, when preparing for disasters, should collaborate with all facilities in their jurisdiction, rather than use a targeted approach based upon facility characteristics.

The studies examining interventions designed to improve preparedness demonstrated effectiveness of staff training in psychological first aid,Reference Brown, Bruce and Hyer 27 general preparedness training,Reference O’Brien, Selod and Lamb 28 and review of the facility’s plan by local emergency management. 13 These studies were not randomized and were heterogeneous in their design and definition of preparedness. Thus, low-level evidence (level IV) suggests that certain types of staff training and review of facility plans by local emergency management may improve long-term care facility preparedness. Although resident training has been demonstrated to improve resident knowledge about disaster preparedness in assisted-living facilities,Reference Feret and Bratberg 39 we found no studies that looked at resident training in nursing homes. We also suggest that long-term care facilities participate in community disaster exercises. Although we did not find studies specifically examining the effectiveness of participation by long-term care facilities in disaster exercises, hospital participation in disaster exercises appears to improve effective disaster response.Reference Agboola, McCarthy and Biddinger 40 Despite reports of difficulties faced by some hospitals receiving evacuees from long-term care facilities related to Hurricane Sandy,Reference Adalja, Watson and Bouri 41 , 42 several reports following Hurricane Sandy noted improved coordination of community emergency planning and response, and that this contributed to more effective response. 42 - Reference Gibbs and Holloway 44 We thus agree with official governmental agencies and others who have recommended coordination of community planning and response. 12 , 13 , Reference Gibbs and Holloway 44 , Reference Zork 45 In addition, facilities wishing to improve their disaster preparedness should routinely provide training for staff (and perhaps residents) on hazards that may impact their facility. In this regard, CMS has published disaster preparedness educational tools for long-term care facility residents and their families 46 and has encouraged long-term care ombudsmen to work with local emergency management and public health to educate and train long-term care facilities’ staff and residents about emergency preparedness, planning, and response. 16

All of the studies examining health effects following a disaster consistently demonstrated a decline in the health of residents residing in long-term care facilities experiencing a disaster. This includes an increased mortality, more frequent hospitalization, and functional decline. These findings were demonstrated for both hurricanes and earthquakes. A foreign language article excluded from our full review contained an English-language abstract that mentioned similar adverse health effects for 140 residents of a nursing home evacuated because of floods in France.Reference Mantey, Coccoz and Boulogne 47 All of these studies suggest that adverse health effects persist for at least 90 and perhaps 250 days.

Even when occurring for administrative reasons, relocation of nursing home residents results in adverse health effects including excess mortality.Reference Castle 48 Thus, it is no surprise that natural disasters result in adverse health effects in nursing home residents because evacuation frequently occurs. In this regard, the 4 studies comparing outcomes of facility residents who evacuated versus sheltering-in-place are especially informative.Reference Dosa, Grossman, Wetle and Mor 6 , Reference Castro, Persson and Bergstrom 35 - Reference Dosa, Hyer and Thomas 37 All 4 studies demonstrated worse health outcomes in evacuated residents, suggesting that evacuation aggravates adverse health effects associated with the disaster alone. A finding of excess mortality among evacuated nursing home residents compared to residents who sheltered in place was also demonstrated in the foreign language French study.Reference Mantey, Coccoz and Boulogne 47 We conclude that the best evidence demonstrates that compared to sheltering-in-place, evacuation of nursing home residents is associated with more adverse health effects including excess mortality. Also, when interviewed by experts, administrators of facilities that evacuated reported more operational difficulties than administrators of facilities that sheltered in place.Reference Dosa, Grossman, Wetle and Mor 6 , 12 We therefore feel that the evidence supports a policy recommendation that local government should carefully consider mandatory evacuation orders for long-term care facilities, because evacuation of long-term care facility residents likely results in more adverse health effects than does sheltering-in-place. Previous authors have discussed the decisional complexity of evacuation, which should include evaluation of disaster, facility, and resident attributes.Reference Dosa, Hyer and Brown 2 , Reference Dosa, Grossman, Wetle and Mor 6 , Reference Dosa, Hyer and Thomas 37 Our conclusion is consistent with the recommendations of others.Reference Dosa, Grossman, Wetle and Mor 6 , Reference Dosa, Feng and Hyer 30 , Reference Castle and Engberg 31 , Reference Brown, Dosa and Thomas 33 , Reference Thomas, Dosa and Hyer 36 , Reference Dosa, Hyer and Thomas 37

We also conclude that because nursing home residents are particularly vulnerable to adverse health effects following disasters, local health care communities and governments should be prepared to provide additional medical support to these residents during the response and recovery phases of a disaster. Thomas et alReference Thomas, Dosa and Hyer 36 reached a similar conclusion following their study of excess hospitalization after Hurricane Gustav.

Finally, we were impressed with the small number of studies looking at interventions to improve preparedness and response. Based on the magnitude of the problem, additional well-designed studies are needed to understand what interventions would result in improved outcomes for residents in long-term care facilities that experience disasters. As have others,Reference Dosa, Grossman, Wetle and Mor 6 , Reference Hyer, Brown and Christensen 7 , Reference Castle 22 , Reference Dosa, Feng and Hyer 30 , Reference Dosa, Hyer and Thomas 37 we recommend that academic geriatric, public health, and emergency management practitioners design more studies to identify and understand these issues, and that private and public research foundations offer support for this research.Reference Hyer, Brown and Polivka-West 49

CONCLUSIONS

Long-term care facilities house some of our nation’s most vulnerable citizens. The literature demonstrates that residents of long-term care facilities that experience a disaster are especially likely to suffer adverse health effects. The current literature provides limited evidence to guide recommendations about how to improve disaster preparedness and response for long-term care facilities, but nonetheless supports several specific recommendations including some that have been previously based on expert opinion.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2016.59