Introduction

During the period of the Communist regime (1945–89), Romanian modern music was subject to political pressure that resulted in aesthetic limitations. Nevertheless, after the cultural ‘thaw’ that came from Moscow in the 60s, novelty and boldness in musical language started to be tolerated, and this coexisted with the socialist realism imposed by communist ideology. A group of Romanian composers established new directions, inspired by French, German and Polish music, the most prominent being Pascal Bentoiu, Theodor Grigoriu, Ștefan Niculescu, Tiberiu Olah, Aurel Stroe and Anatol Vieru. Their outputs, largely unfamiliar to the Western public, represent a true Romanian School of composition, comparable with the Polish one, as Martin Anderson explained in 2019:Footnote 1

One of the more curious phenomena of musical life in the post-War Communist bloc in eastern Europe was the flourishing of two schools of avant-garde composition, in Poland and in Romania, under regimes which otherwise frowned heavily upon artistic experiment. It wasn't that the commissars in those two countries were any more artistically enlightened than the thought-enforcers elsewhere in the Communist world; in Romania, rather, it was a happy side-effect of a realignment in international politics, with the regime keen to demonstrate a degree of ideological independence from the Soviet Union, and so in 1963 Romanian artists were given the green light to experiment. In the first years of his rule, Nicolae Ceauşescu, general secretary of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965, fostered this non-alignment – for a few brief years – and although the cultural manacles were reimposed in 1971, for Romanian composers the cat was now out of the stylistic bag.

Among these male figures, a generous, aristocratic and enigmatic woman asserted herself as one of the most original and powerful creative voices in Romanian music: Myriam MarbeFootnote 2 (1931–1997). She became the first female composer of international calibre in the history of Romanian music. It is important to emphasise that she embodied for younger generations what it meant to be a female composer in the world of music; she was a role model, successfully inspiring and encouraging many new talents. She taught composition and counterpoint at the Ciprian Porumbescu Conservatory of music (now the National University of Music Bucharest), her charismatic personality providing an example for aspiring female students, some of whom, over time, became established composers themselves.

Of these students Violeta Dinescu is one of the most remarkable and the first to become internationally renowned; she remained in contact with Marbe until her very last days in December 1997. Dinescu was born in 1953 in Bucharest. After graduating from the Gheorghe Lazăr High School with a specialisation in mathematics and physics, she decided to follow her passion for music and enrolled at the Music Conservatory in Bucharest (1972–78). During her studies as a composition student in Myriam Marbe's class she absorbed every aspect of musical education and graduated with three bachelor diplomas: composition, piano and pedagogy. She was awarded a George Enescu scholarship for excellence and in 1977–78 specialised in composition, studying exclusively with Myriam Marbe.

This encounter was decisive for her future in music. In 1982, Dinescu was allowed to travel to Mannheim to receive a composition prize. She had also been awarded a grant to stay in Germany for a few months, but when she decided to stay longer she was unable to extend her visa and was afraid to return to Romania after its expiry date. Her only choice was to remain in Germany, with no hope of ever returning to her country and to her family. From this dramatic moment on she struggled to bring her parents to Germany and started to build her career as one of the most remarkable contemporary composers of today. The recipient of more than 90 composition prizes,Footnote 3 grants and commissions, in 1996 she was appointed professor at the University Carl von Ossietzky in Oldenburg for applied composition, where she founded the Archiv für osteuropäische Musik, the Komponisten Colloquienreihe between 1996–2021 and the Symposienreihe ZwischenZeiten [ShiftingTimes] from 2006 to 2021. Her operatic works include Der 35 Mai (1986), a children's opera after Erich Kästner, commissioned by the Mannheim National Theater; Eréndira (1992), based on Gabriel García Márquez's The incredible and sad tale of innocent Eréndira and her heartless grandmother and commissioned by the Munich Biennale; and Hunger and Thirst, after Eugène Ionesco, premiered in 1986 at the Freiburger Theater.

Other theatrical works include the chamber opera Schachnovelle (1994), after Stefan Zweig, commissioned by the Schwetzingen Festival, and the ballets Effi Briest, after Theodor Fontane, commissioned by Magdeburger Staatstheater, and Der Kreisel, after Eduard Mörike, written for the Ulmer Theater. Her music for the silent movies Tabu and Nosferatu, by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau,Footnote 4 has been performed internationally. Dinescu has also written oratorios, concerti and orchestral works, as well as vocal, choral and chamber music.

The Graphic Representation of a Hyperbolic Musical Space in Gehen wir zu Grúschenka

Violeta Dinescu's recent piece Gehen wir zu Grúschenka [Let's go to Grúschenka], for solo cello with voice ad libitum (2021),Footnote 5 raises a fundamental question: how do we imagine music in a mental musical space? Given that the concept of space is intricately connected with time, we might also ask: how does our representation of musical space influence musical timing? These questions are important for a deeper understanding of the composer's conceptual spaceFootnote 6 and provide innovative criteria for musicological commentary and analysis. Imagining a piece of music evolving in either a Euclidean or a non-Euclidean space may suggest new typologies in music aesthetics and music theory; it is also important to consider whether this dichotomy holds true for both performers and listeners.

For architects the most valuable ability is spatial thinking, the ability to mentally ‘see’ in space. Composers also need to be able to ‘see’ music in their mental space and to move freely within it, but in what kind of space are composers imagining their music? A classical, linear one or a curved, distorted, hyperbolic one? Being aware of these concepts and discriminating between them may also trigger musicians’ creativity. In her research into the dynamics of creativity in the human's brain, Margaret Boden speaks about dealing with ‘cognitive maps of musical space’:

The ‘mapping’ of a conceptual space involves the representation, whether at conscious or unconscious levels, of its structural features. The more such features are represented in the mind of the person concerned, the more power (or freedom) they have to navigate and negotiate these spaces. A crucial difference – probably the crucial difference – between Mozart and the rest of us is that his cognitive maps of musical space were very much richer, deeper, and more detailed than ours. In addition, he presumably had available many more domain-specific processes for negotiating them… mental maps enable us to explore and transform our conceptual spaces in imaginative ways.Footnote 7

From the dawn of music notation in the medieval era, music was encoded with signs for pitch and duration in a two-dimensional Euclidean plane of graphic representation, on a variable number of parallel lines that eventually became the conventional five-line stave. We read music from left to right in a linear way and usually we measure a regular pulsation, which we call metre, indicated by time signatures, as we follow the timeline. The parallel staves suggest the flowing of music according to a proportional division of duration (rhythmic values) and tempo (speed), and, as Euclidean geometry predicts, they never meet.

But what if the composer imagines staves that are not parallel (see Example 1) and rhythmic values that are not proportional divisions of rhythmic pulsation? What implications could this type of imagination have for music? How do we decode this non-conventional spatial representation of music and disproportional timing? The non-parallel staves will collide at one point, or move infinitely far apart, unless we shift our imagination to a non-Euclidean geometry and, thus, to a hyperbolic space. As predicted in a non-Euclidean geometry, parallel lines curve away from each other, increasing the distance between them indefinitely. This graphic representation suggests distortion, as if the staves are drawn in a curved space and the music flows in a non-Euclidian hyperbolic conceptual space; in turn this has consequences for different layers of the musical structure and our perception, which I will discuss later.

Example 1: Violeta Dinescu, Gehen wir zu Grúschenka, p. 2 (all score examples are reproduced with the permission of the composer).

Variation, Transformation, Distortion

A clear-cut distinction should be made between traditional variation, transformation processes and distortion. Variational processes in Western classical music generally apply to motives or phrases, preserving the core of the original and its durational proportions. More advanced variations transform the given structure and these transformation processes occur gradually and organically. For example, in the spectral musicFootnote 8 of Gérard GriseyFootnote 9 or Tristan Murail, time seems to dilate within certain spectres, whereas in Ligeti's dense sound masses, as in Atmosphères (1961), inner micro-movement slowly changes the content of the musical textures.

Distortion is also frequently used but is less extensively theorised. It offers a more dramatic change of the original – non-linear, unpredictable and disruptive – like diving into the rabbit hole along with Alice in Wonderland. Lewis Carroll (the Oxford mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) imagined Alice's adventures in a non-Euclidean space: bizarre characters act nonsensically in disproportional, hyperbolic space. Dinescu's graphic representation of distortion and disruption of the musical content also mirrors the surrealism of Salvador Dali or the visual paradoxes of M. C. Escher.

Graphic notation and open scoresFootnote 10 are not new phenomena. Since the 1950s many works have entirely or partially replaced conventional musical notation, providing visual symbols to trigger the performer's free responses, and John Cage, George Crumb, Iannis Xenakis, Krzysztof Penderecki and Morton Feldman all found original graphic solutions for advanced instrumental techniques. Violeta Dinescu's use of distorted graphic notations in Gehen wir zu Grúschenka is an organic answer to her aesthetic concept for this work. According to her programme noteFootnote 11 the work represents a ‘psychogram’ of the character Grúschenka from Dostoyevsky's novel The Brothers Karamazov. Dinescu combines archaic and modern features, mixing advanced instrumental techniques with echoes of the Romanian traditional style, Doïna, based on parlando rubato rhythms: a free, non-divisionary, irregular unfolding of duration values.

Gestures and Events in a Hyperbolic Musical Space

To depict Grúschenka's moods and psychological conflicts, Dinescu unfolds gestures and events that appear to follow a subjective timeline: ‘different layers of memory persist simultaneously in Grúschenka's mind, which causes unpredictable impulses in her actions’.Footnote 12 Conventionally, the representation of different emotional states in music-drama is undertaken lyrically, but here it is musical time that seems to contract or expand according to Grúschenka's state of mind, an abstraction of the lyrical content that enables a subtle, imaginative immersion in the character's archetypal being.

Dinescu's free and unpredictable musical gestures are, nonetheless, extremely well controlled in terms of dynamics, attacks and registers. Nothing is linear or regular but instead evolves in an imaginary curved hyperbolic space characterised by abrupt dynamics, sudden register shifts, timbral shadows, powerful contrasts of durations and structural elements, sotto voce moments and moments of forceful noisy sonorities. The oscillation between nanomusic and hypertimbreFootnote 13 (see Example 2) is dramatic, yet also abstract and subtle.

Example 2: Violeta Dinescu, Gehen wir zu Grúschenka, p. 5.

Timbre in a Non-Euclidean Conceptual Musical Space

Violeta Dinescu extends the expressive range of her chosen solo instrument, the cello, not only by integrating the performer's voice – speaking, crying or singing – but also by prolonging the performer's gestures, simulating vibrations in the air. The score shows words and sentences in a variety of font sizes, sometimes surrounded by curved lines, suggesting prolonged vowels or simply prolonged air expiration. The result is a hypertimbre (see Example 3), richly varied in its expressive potential, that behaves like a hypertext, generating timbral and cultural hyperlinks.

Example 3: Violeta Dinescu, Gehen wir zu Grúschenka, p. 3.

There are timbral distortions in both instrument and voice that explore the grey area between harmonic and inharmonic sounds.Footnote 14 A cello sound that is produced and sustained conventionally, with a normal vibrato, is stable and balanced, enhancing its harmonicity, but when other techniques are involved that enhance the transient attacks and other noisy elements, inharmonicity is more present. Dinescu's exploration of this timbral shadowing along the sound–noise continuum is always refined; inharmonicity appears as a timbral distortion of the imaginative and temporal space of the music.

Intertextuality in a Cultural Hyperbolic Space: Herzriss – Aus deinem Herzen kannst du die Liebe nicht ausreißen

Herzriss – Aus deinem Herzen kannst du die Liebe nicht ausreißen [Heartbreak – You cannot uproot love from your heart] is an opera for voice(s), percussion and cello (2005, revised 2021),Footnote 15 in which Dinescu explores another perspective on the perception of musical mental space, extending into cultural space. The opera is in 11 parts and an epilogue. The coexistence of five characters within a hallucinatory depiction of an archetypical woman creates a series of non-linear cultural hyperlinks, and the opera's atemporal and multidimensional narrative creates interconnected layers of meanings and musical ethos, an imaginary cultural hyperbolic space.

Mythical Female Figures

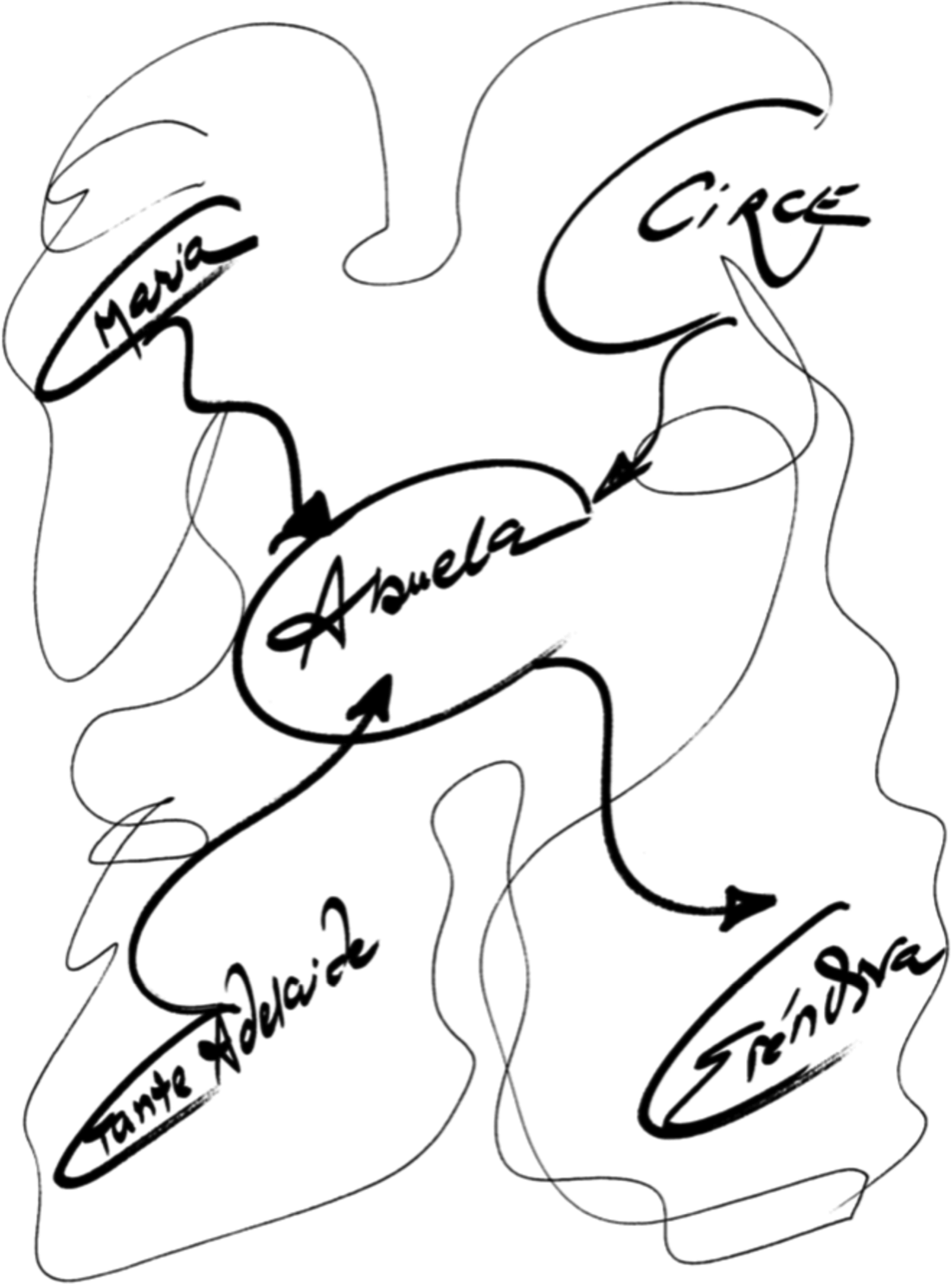

In Herzriss Dinescu brings together key moments from her own previous operatic and vocal–symphonic works. Five powerful women – Circe, Eréndira, Abuela, Maria and Tante Adelaïde – represent the oneness of the female soul. The original source for Circe is Dinescu's Concerto for variable orchestra groups with obbligato soprano solo (the text is from Homer's Odyssey), for Eréndira and Abuela her opera Eréndira (based on Gabriel García Márquez's La increíbile y triste historia de la cándida Eréndira y de su abuela desalmada), and for Tante Adelaïde and Maria her opera Hunger and Thirst (based on the play by Eugène Ionesco).

The characters, ranging from Greek mythology to modern theatre, represent five hypostases of the women's psychological features that evolve in ‘simultaneous time’.Footnote 16 Circe has the power to make them all appear and disappear, as if they are imprisoned within the labyrinth of one woman's mind, and the plot freely combines stories and characters with elements of surrealism, absurd, distorted physical or mental features, mythical dimensions and the supernatural (see Example 4). Eugène Ionesco presents his characters in a disrupted reality: Tante Adelaïde is dead but behaves as if she were alive, in the midst of her family members; Maria plays hide-and-seek with her desperate husband, Jean, who disappears; she searches for him in ever smaller places, even in the drawers, like an embodiment of the eternally patient, loving wife.Footnote 17

Example 4: Violeta Dinescu, Herzriss – Aus deinem Herzen kannst du die Liebe nicht ausreißen, front cover.

Gabriel García Márquez created an exaggeratedly evil character, the ruthless Abuela, in opposition to her supposed granddaughter, the innocent teenager Eréndira. In the story Eréndira is dramatically transformed into an even viler person than the grandmother, who had dominated and manipulated her; she becomes a new, fiercer and more sinister Abuela. Circe transforms men into animals and is defeated by Ulysses, who manages to reject her charms and escape her spells and magic traps.Footnote 18

The accompanying instruments, cello and percussion, reflect the actions and states of mind of the characters. The cello provides a continuum, unifying different contexts, sometimes with bass drones that suggest Byzantine chant. The percussion instruments add a more archaic flavour to the piece and are specifically assigned to the characters:

Circe: wooden semantron (the Romanian ‘toaca’), spring drum, Tibetan singing bowls, Tibetan cymbals, Japanese temple bell;

Tante Adelaïde: tamburino, scrap metal, Burmese bells, bodhran with gummi-balls, crotales, glocken, gong;

Eréndira: bowed glockenspiel;

Maria: glockenspiel/chimes.

Abuela: gong, crotales, glocken, and two bodhrans

There are two versions of the score: one assigns parts to five different singers, who finally combine in the Epilogue, a setting of the ‘Dona nobis pacem’ that Dinescu wrote especially for this multiple-voice version; the other is to be performed by a single singer who can reach all the required registers and can express all the vocal colours (in this version, the ‘Dona nobis pacem’ is performed with pre-recorded voice tracks).

The five characters are represented by different female vocal types: Eréndira is a lyric coloratura soprano, Tante Adelaïde a dramatic coloratura soprano, Maria a mezzo-soprano, Circe an alto and Abuela a contralto. Imagining the five different voices as a single creature, capable of so many timbral nuances and expressions, Dinescu creates a macrostructural hypertimbre. The original version, for a single singer, was written in 2005 especially for the vocal phenomenon Christina Ascher (1944–2016), who had begun her vocal studies as a coloratura soprano at the Julliard School and later developed her lower contralto register, without losing her technical command of the higher register.Footnote 19

The composer offers a condensed narrative with mythical resonances. The omnipresent Circe and her magic establish the story in a mythological world, but the other, more profane, characters also share universal and atemporal features. According to Mircea Eliade, the rituals and myths of various cultures and religions enable people to ‘return’ to ‘illo tempore’, the original mythical age when everything was created, and to recreate the cosmos in an eternal cycle. In this ‘eternal return’ time is felt to be cyclical, whereas for profane actions time is felt to be linear, following the direction of history.Footnote 20 In her programme note, Dinescu refers to a simultaneity of actions occurring in a multidimensional and expanded present; to these I would add ‘simultaneous cultural hyperlinks’, the atemporal combination of the ethos of different cultures: Ancient Greek, South American, Romanian and French. Thus, the scenario can be read as an intertextual hypertext with interconnected layers.

Musically, Dinescu achieves this through a variety of means. She provides a timbral environment rich in vocal melodic inflections and modulating colours. Her chosen percussion instruments evoke archaic sonorities from the deepest strata of Ancient Greek music, combined with more remote cultures, such as those of the Middle and Far East, to convey a sense of universality. The resonance of tragedy is present throughout and the work's aesthetic is comparable to Iannis Xenakis’ vocal music for the Oresteïa, particularly Kassandra (1987) and La Déesse Athena (1992), or Aurel Stroe's opera Orestia, in its transhistorical combination of modernity and antiquity.

An Overview of the 11-Part-and-Epilogue Opera; Cultural Hyperlinks via Timbre

The graphic representation of the vocal part of the opera Herzriss resembles an oscillograph that displays variations of amplitude and frequency across the timeline of the story according to the characters represented. Pitch is further modulated and distorted on particular vocals or phonemes as the graphic suggests. Timbre is constantly changing and evading traditional vocal techniques: the timbres employed in the vocal part include whispers, large glissandi, portamenti and microtones, and the entire vocal part can be seen as a hypertimbre. The notation is almost entirely senza misura, but a sense of pulsation, proportional durations and the succession of events is preserved. The range of dynamics for the voice and the instruments, always very precisely indicated, is huge, allowing for dramatic sonorities and contrasts.

I. The first part of the opera Herzriss – Aus deinem Herzen kannst du die Liebe nicht ausreißen is assigned to the alto, Circe, who wonders why her magic potion is not working on Ulysses. The text, from the first canto of Homer's Odyssey, is fragmented across the six appearances of Circe. The entire text, when all the pieces of the puzzle are put together, reads thus:

Wer, wes Volkes bist du? Und wo ist dein Geburtstadt? Staunen ergreift mich, da dich der Zaubertrank nicht verwandelt! Denn kein sterblicher Mensch ist deinem Zauber bestanden, welcher Trank, sobald ihn der Wein die Zunge hinabglitt. Aber du trägst ein unbezwingliches Herz in dem Busen! Bist du jener Odysseus, der, viele Küsten umirrend, wann er von Ilion kehrt im schnellen Schiffe, auch hierher kommen soll, wie der Gott mit goldenem Stabe mir sagte?Footnote 21

The vocal part grows out of unintelligible, pre-linguistic sounds and has an hallucinatory force that challenges aural perception, its timbral range imbued with dramatic and cultural meanings. Inhuman, modulated vocalisations, such as screams and ululations, contrast with whisper-like sounds, transcending the traditional techniques of cultivated singing and characterising Circe's supernatural ‘psychogram’. Dinescu creates a quasi-recitative for the voice that contains repetitive or formulaic sounds, microtones gliding between small intervals and glissandi fluctuating across wide intervals. Non-metrical improvisatory rhythms articulate the character's state of mind, and the unpredictable, non-linear unfolding of events is matched by dynamic contrasts that are sometimes subtle, sometimes wild (Example 5).

Example 5: Violeta Dinescu, Herzriss, Circe, Part I, p. 1, undulating vocal timbre.

Particularly at the beginning of Herzriss, the atmosphere seems to allude to the awakening of the Sphinx in Enescu's opera Œedipe (1936), and Dinescu's opera also opens in ancient Greece, but extends that culture with echoes from the Balkans and historical Thrace. Two of the oldest and most characteristic folk instruments in Eastern Europe provide accompaniment: the spring drum, known in Romanian as ‘buhay’ and used in Romania during various rituals that originated in the pre-Christian age, and the wooden semantron (‘toaca’ in Romanian), used in Greek and Romanian Orthodox churches and monasteries to call people to worship. These timbres link to Eastern Europe cultures and, further east, to Asia, evoking a universal space and time: Dinescu uses Japanese temple bells, Tibetan singing bowls and Tibetan cymbals, combining their timbral and cultural ethos with the East European instruments.

The percussion instruments are made of metal, wood and skin. Unlike the human voice, which produces harmonically complex sounds in vowel singing, meaning that more energy relies on the harmonic spectrum, the sounds of these percussion instruments are inharmonic. Inharmonicity,Footnote 22 defined as the result of a set of partials that are non-integer multiples of the fundamental frequency, is a characteristic of many percussion instruments, and their noisy instability provides Dinescu with a rich palette of distorted, twisted, swirling sounds: windy and whistling from the spring drum, short but resonant from the semantron, gliding from the Tibetan singing bowls or cymbals. The spring-drum tube is sometimes used as a resonating body for the voice. These subtle, ever changing timbral nuances evoke Eastern and Far Eastern cultural identities but then surpass them, fusing them in a mythical spacetime.

II. The second part plunges into an abyss of absurdity and surrealism. Tante Adelaïde is dead but is paying an unexpected visit to her family. She complains hysterically about always being underestimated even though ‘she knows everything’. She talks about eating and drinking, about her beauty and the red blood in her veins, as if she were still alive.

The profile of the vocal line uses wide intervals and lies in the higher register of a dramatic coloratura soprano. It features expressionistic, repetitive, descending figures from a very high to a low register, which sound like laughs or screams (see Example 6), undulating glissandi, short quasi-percussive sounds and parlato passages, all contributing to the music's representation of Tante Adelaïde's nonsensical discourse.

Example 6: Violeta Dinescu, Herzriss, Tante Adelaïde, Part II, p. 11.

The timbral environment is made up of the cello and three percussion instruments: a membranophone, tambourine and metal instruments (scrap metal and Burmese bells). The tambourine, now usually associated with Hispanic or Italian traditional music, has Arabic origins and was familiar in Mesopotamia, Palestine and Egypt, as well as in Greece and Rome. Dinescu's choice of the tambourine also sets up a cultural hyperlink with Southern Italian folk music, where the tarantella is accompanied by tambourines. The tarantella is a dance that originated in an ancient therapeutic antidote for the bite of a species of tarantula spider that could cause convulsions, hysteria or madness, a condition called ‘tarantism’ (see Example 7). Tante Adelaïde's hysterical behaviour, located by Ionescu on the border between life and death, is culturally associated with the tarantella dance and with the timbre of the tambourine. The other metal instruments, the scrap metal set and the Burmese bells, have different cultural backgrounds, but in combination with the sonority of the tambourine's metal discs they create an augmented metallic timbre, a hypertimbre. This timbral ‘alloy’ serves to depict Tante Adelaïde's ‘unhinged’ character.

Example 7: Violeta Dinescu, Herzriss, Part II, pp. 11–12; the tarantella rhythm is circled.

The frenzied shaking of the metal objects by the singer herself becomes almost paroxysmic. The voice combines easily with the cello, their complex harmonic timbres tending to fuse together and to enhance one another, in what might be called an augmented timbre,Footnote 23 but vocal timbre does not fuse with the complex inharmonic sounds of the metal instruments. They reject each other, preserving their identity, and the result is a timbral segregationFootnote 24 that suggests madness and Tante Adelaïde's surreal absurdity. Rhythmically, irregularity prevails but there are brief moments with a regular pulse and rhythmic formulae. On pages 11 and 12, for example, alternating time signatures such as 2/4, 3/8, 3/4, 5/8, 6/8 and 5/4 establish a regular quaver pulse but not a regular metre. Although they are inconsistent, there are also short references to the tarantella's ternary rhythmic formula of crotchet followed by quaver (see Example 7).

This section also features a repetitive rhythmic formula, based on the trochee metre (long–short or heavy–light) but with a binary pulse: dotted quaver followed by semiquaver (see Example 8)

III. The third part resumes Circe's spiralling narrative, adding fragments to her monologue. It returns to the austerity of the Greek/Romanian semantron, together with Japanese temple bells, crotales and cello. The voice also returns to some of Circe's earlier vocal gestures, such as quasi-tonal formulae, undulating vibrated glissandi and microtonal sliding pitches, but also introduces wider intervallic leaps and descending chromatic cells. Once again Circe's part stretches the boundaries of human speech beyond intelligibility, deconstructing words and distorting them with extreme dynamics. In the first part Dinescu took the voice from unintelligibility to intelligibility; in the third part she reverses the process and it finishes, as the first part began, with the interjection of decomposed syllables (see Example 9). Unlike the first part, however, the semantron begins with a repetitive rhythmic formula, and at the end of the third part the cello has a solo cadenza that mirrors and comments on the voice's gestures.

IV. The fourth part inhabits the magic realism of Gabriel García Márquez's story Eréndira, and adopts an even more expressionistic approach to the voice. Dinescu depicts the fierce, ruthless Abuela, Eréndira's grandmother, with various unconventional vocal techniques, from savage acciaccature and rolled ‘r’ sounds to glissandi with trills, eccentric laughs and Sprechgesang (see Example 10).

Example 8: Violeta Dinescu, Herzriss, Part II, p. 10.

Example 9: Violeta Dinescu, Herzriss, interjections accompanied by a repetitive rhythmic formula, Circe, Part III, p. 20.

Example 10: Violeta Dinescu, Herzriss, Abuela, Part IV, p. 23.

The timbres seem to be complicit with Abuela's diabolic persona, gathering metal and membranophones: gong, crotales, glocken and two bodhrans (Irish frame drums), which are played with gummi-balls and iron chains on their inside. The rolling of the gummi-balls, four in the small bodhran and two in the larger one, produces a continuous threatening roar, perfectly matching the character of Abuela as she swears horribly, laughs stridently and dreams of her grotesque past. A cello epilogue concludes this powerful scene.

V. Circe's overwhelming power is unleashed in the fifth part, in which her utterances are in a language beyond comprehension, magical and atemporal. The only familiar words are ‘Wer bist du?’, followed by decomposed syllables, interjections and paralinguistic sounds and, eventually, a cello coda.

VI. The sixth part introduces a contrasting musical character, Eréndira, Abuela's so-called ‘granddaughter’. The ethereal sound of a bowed glockenspiel sets an intimate atmosphere as Eréndira confesses that she was planning, together with her lover, to murder Abuela. She imagines herself in a beautiful house where at last she can command respect. Her voice is accompanied by the cello, deploying a vast gamut of extended techniques to create inharmonic sonorities. Offstage the singer plays the spring drum, enhancing the drama of this scene and linking it to the next one.

VII. The seventh part returns again to Circe, accompanied by her characteristic instruments, the spring drum and the semantron. The intelligibility of her words is restored, but her intonation remains unstably microtonal, and there are disconcerting emphases on certain consonants. Nevertheless, in the midst of this vocal quicksand, there are certain stable pitches on which the voice can rely as intonational anchors.

VIII. Abuela, the villain grandmother of Eréndira, reappears. The voice, in the alto register, starts with a lament-like melodic line in 3/4, perhaps also suggesting a waltz lullaby, centred on a C minor scale. Soon, however, she returns to her curses and savage screams, accompanied by bells, gong and crotales (Example 11).

IX. Circe resumes her questions to Odysseus, her vocal line encompassing both large intervals and chromatic minimalistic figures, over a continuous improvisation on the semantron.

X. The fifth character, Maria, from Ionesco's Hunger and Thirst, appears in the tenth part. She embodies qualities of love and devotion. Her husband, Jean, mysteriously disappeared during a sort of hide-and-seek game and she is constantly searching for him in all sorts of unlikely places. Reality has become absurd, space and time distorted. ‘You cannot uproot love from your heart’, she sings, a phrase that gives the whole work its title.

Example 11: Violeta Dinescu. Herzriss, Abuela, Part VIII, p. 55.

Glasglocken (glass bells), cello and suspended cymbal create the timbral medium for Maria's monologue. The music begins serenely with vibrating glasglocken and the cello swinging peacefully between D and A, with chromatic acciaccatura on E♭. The voice continues with a variation of this repetitive swinging figure (see Example 12) chromatically inflected with G♯s and B♭s. The cello moves on to an ostinato on the C string over which the voice performs undulating formulae, glissandi, repetitive sounds and Sprechgesang.

Example 12: Violeta Dinescu, Herzriss, Maria, Part X, p. 70.

This scene ends with Maria obsessively repeating the phrase ‘you cannot uproot love from your heart’.

XI. Circe's text is finally completed with Homer's words: ‘as the God with the golden sceptre tells me?’ Initially the voice is accompanied only by the spring drum, used as a resonating body, its whistling combined with Circe's breathy whispers. The semantron returns, its irregular resonant strokes articulating an aksak-like rhythmic formula and re-establishing our sense of Circe's implacably powerful character.

In 2021 Dinescu added the Epilogue, with five female singers for the five characters. Her programme note describes how the voices unite in unison, heterophony and flexible canon to sing together a prayer: ‘Dona nobis pacem’. The composer is not alluding to the Western Catholic Church tradition but to the origins of both this prayer and the Agnus Dei in the Eastern liturgy; both texts were introduced in the Western mass only in the eighth century.Footnote 25 Within the same layer of archaic cultural references Dinescu also integrates a lament-like song, composed in the spirit of the ancient musical traditions of the North Romanian Maramureș, and based on various syllables that recall the ‘colour of the ancient Greek language’.Footnote 26 An earlier version of this lament (in the traditional Romanian Doïna style) was presented as a 3/4 lullaby at the beginning of Abuela's intervention in Part VIII.

In Byzantine church music, melismatic melodic lines are accompanied by an ison, a bass drone, and, at the macrostructural level, Dinescu sees the quasi-obligato cello part as a ground for the entire piece, acting as a complex, microtonal fluctuating ison.Footnote 27 Her use of graphic notation, typical of much of her work, allows the performers a certain freedom of creative interpretation and improvisatory imagination.

Time and Space Distortion (Vortex) in the Herzriss Scenario

The portrayal of the female soul in Herzriss is many-layered. Each character appears within her own distinctively developing timeline, but at the same time is part of a temporal vortex that unifies the entire work, described by the composer as a ‘simultaneity of paroxysmal moments’. The stories are unified by the cyclic appearance of the mythical character, Circe, through whose magic the other characters appear to be summoned. They become captive in the augmented temporality and spatiality of the main narrative created by Circe, yet in turn the stories of Tante Adelaïde, Abuela, Eréndira and Maria seem to extend the timescale of the narrative, while at the same time consolidating the main subject of the work, the female soul in all its multidimensionality. Unlike Gehen wir zu Grúschenka, the graphic notations in this score do not involve distorted staves, but the complexity of the scenario and its non-linear, uneven and irregular content nevertheless suggest the same preoccupation with a non-Euclidean, curved and twisted conceptual space.

Conclusion

This article has considered our awareness of conceptual space, the mental space within which our imaginations operate. Thinking about mental musical space implies a difficult double operation – to imagine the way we imagine music – but conceptual space is the place of our creativity, and we should try to become more aware of its quality. How composers represent music in their own mental space can also help us to understand their work. My interpretation and analysis of Violeta Dinescu's music through this prism confirms that her musical imagination is non-Euclidean, inhabiting a hyperbolic space with a high degree of complexity in every musical parameter. I hope, too, that I have been able to open an innovative musicological perspective that considers the quality of the composer's creative imagination and the depth of the conceptual space within which musical ideas arise, move and grow.