Introduction

Sleep disorders are on the constant rise (Acquavella, Mehra, Bron, Suomi, & Hess, Reference Acquavella, Mehra, Bron, Suomi and Hess2020). One of the less common sleep disorders is narcolepsy. There are two types of narcolepsy: narcolepsy type 1 or narcolepsy with cataplexy, and narcolepsy type 2 or narcolepsy without cataplexy (Dauvilliers & Buguet, Reference Dauvilliers and Buguet2005; Šonka, Šusta, & Billiard, Reference Šonka, Šusta and Billiard2015; Trotti & Arnulf, Reference Trotti and Arnulf2020). Additional symptoms and signs of narcolepsy type 1 include excessive daytime sleepiness, sleep paralysis, hypnagogic and/or hypnopompic hallucinations, cataplexy, difficulty staying asleep during the night, and restorative sleep and naps. Cataplexy is especially worrisome for patients because it can be triggered by stress, emotions (e.g., anxiety), and behaviours (e.g., laugh). Moreover, during a cataplexy episode, the patient is awake but is temporarily unable to move body parts or the whole body (Dauvilliers, Siegel, Lopez, Torontali, & Peever, Reference Dauvilliers, Siegel, Lopez, Torontali and Peever2014). Currently, pharmacological treatment of narcolepsy is troublesome because of the side effects, suboptimal effectiveness, development of drug tolerance, and economic and financial burden for patients and healthcare systems (Thorpy & Hiller, Reference Thorpy and Hiller2017; Wozniak & Quinnell, Reference Wozniak and Quinnell2015).

Cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is cost-effective in managing insomnia and its comorbid problems like depression and anxiety (Anderson, Reference Anderson2018; Williams, Roth, Vatthauer, & McCrae, Reference Williams, Roth, Vatthauer and McCrae2013). It consists of sleep hygiene, psychoeducation about sleep and sleep disorders, relaxation techniques, cognitive therapy, and behavioural strategies. CBT-I is recommended by the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, and the American Academy of Neurology as a first-line treatment for chronic insomnia (Krystal, Prather, & Ashbrook, Reference Krystal, Prather and Ashbrook2019). CBT-I is recommended as a first-line treatment, especially for vulnerable populations that are of older age, have complex conditions and comorbidities, experience unwanted side effects, or are on polypharmacy (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Roth, Vatthauer and McCrae2013).

Despite the positive attitudes and interests of psychologists trained in CBT to apply it to narcolepsy and other sleep disorders (Marín Agudelo, Jiménez Correa, Carlos Sierra, Pandi-Perumal, & Schenck, Reference Marín Agudelo, Jiménez Correa, Carlos Sierra, Pandi-Perumal and Schenck2014), there is currently a lack of studies supporting its effectiveness and application in clinical practice. Unlike some other sleep problems, such as insomnia, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is not appropriately explored in narcolepsy type 1 nor strongly recommended by major expert bodies. Experts have developed only a few guidelines based on evidence that recommend cognitive and behavioural interventions in hypersomnia (Marín Agudelo et al., Reference Marín Agudelo, Jiménez Correa, Carlos Sierra, Pandi-Perumal and Schenck2014; Thorpy & Hiller, Reference Thorpy and Hiller2017). These include the Brazilian Society of Sleep Medicine and the European Association of Neurology. Researchers have commonly used isolated behavioural techniques to treat different problems (e.g., sleep satiation for sleepiness) and measured their effectiveness. Only one study used complete CBT treatment for hypersomnia delivered via telehealth (Ong, Dawson, Mundt, & Moore, Reference Ong, Dawson, Mundt and Moore2020). Their research suggests it to be an effective treatment option. Most popular CBT techniques for treating hypersomnia include sleep satiation, stimulus satiation, scheduled naps, hypnosis, lucid dreams, cognitive therapy, muscle relaxation, diet, imagery rehearsal therapy, stimulus control, and systematic desensitisation. Those techniques should be adapted to the type of hypersomnia (e.g., patients with narcolepsy type 1 should receive stimulus satiation for cataplexy, but those with idiopathic hypersomnia should not because there is no cataplexy in the latter). Marín Agudelo et al. (Reference Marín Agudelo, Jiménez Correa, Carlos Sierra, Pandi-Perumal and Schenck2014) explain in their clinical recommendation how CBT for hypersomnia (CBT-H) should be delivered and why.

This case study aims to show how effective are the recommendations and treatment plan for CBT-H in narcolepsy type 1 in clinical practice, as recommended by Marín Agudelo et al. (Reference Marín Agudelo, Jiménez Correa, Carlos Sierra, Pandi-Perumal and Schenck2014). Additionally, this article aims to show how effective it would be to apply CBT on patients with hypersomnia who have psychological and psychiatric problems (e.g., traumatic experience, depression, etc.). Informed consent was obtained from the patient, in which it was declared that the author would like to anonymise this case study and present it to the public in the form of a research case study article. The patient was informed that she could refuse it and that it would not affect her treatment.

Case Narrative

Socio-Demographic Information

A.A. is a 27-year-old female with two children. A.A. is unmarried and unemployed, currently living on her own in a rented apartment while waiting for her disability status because of narcolepsy. She is financially dependent on her boyfriend, who helps with rent and care for her children. A.A. described her relationship with her father as satisfying, and she is not in contact with her mother. She has no appropriate social support system (e.g., friends or supportive patient groups).

Narcolepsy Type 1 Problems

Symptoms started occurring at the age of 17, but the diagnosis of narcolepsy type 1 was confirmed at the age of 22. Cataplexy attacks are frequent, with usually around four episodes per day. Cataplexy is mainly triggered by stress and anxiety, very rarely by laughter. The patient experiences hypnagogic hallucinations, which are only mildly inconvenient for her. Hallucinations come in the form of the sound of opening the door, children walking, laughing, and calling her name. She has trouble initiating nocturnal sleep but has refreshing naps during the day. Tiredness and sleepiness negatively impact her daily activities. She currently takes Pramipexole at night (2 mg), Modafinil in the morning (2 × 200 mg), and supplements: iron (5 mg per day) and vitamin D (1000 international units). No other medications are reported.

Associated Problems

The mother abused the patient during her childhood. A.A. had several traumatic experiences. During childhood and adolescence, she experienced verbal and emotional abuse by peers; her best friend killed himself; she was physically, sexually, and verbally abused by her mother. In adult life, she had a miscarriage, social services took her children for 6 months, her ex-boyfriend abused her, and she had several medical procedures that left her in severe distress. Despite all that, A.A. believes that she is coping appropriately with her traumatic experiences despite having problems with flashbacks. At the start of the treatment, A.A. explained that she wanted to receive CBT treatment for her problems with narcolepsy. She explained that she was currently experiencing problems induced by tiredness and sleepiness. They include passive-aggressive behaviour, being snappy and prone to self-isolation during stress, loneliness, depression, and anxiety caused by combination of sleep problems and reliving some old traumas (e.g., mothers abuse), and having no social support system. When her traumatic memories come back, she tries to solve her problems by cleaning and taking care of children (preoccupation), so she would not think about those experiences.

Medical History

A.A. had a spontaneous miscarriage several years earlier. She has been overweight since she was a child and consequently received nutritional treatment, but it was ineffective. Narcolepsy was first suspected at the age of 17 when she started working. Around the same time, she developed restless leg syndrome. She has visited several psychiatrists and psychologists but never continued her treatment. She had received CBT but left the therapy since it was ineffective. The patient has been diagnosed with panic attacks, anxiety and has a history of sleep paralysis as a child. Other medical procedures include appendectomy, degloved leg, and C-section.

Methods

Study Design

The aim of this study was to test specific techniques and interventions for different type of problems in patient with narcolepsy type 1 who has complex clinical picture since currently there is a lack of information regarding this clinical population. Additionally, this article aims to create a debate why are some useful and easy to implement technique and interventions (e.g., satiation of cataplexy; satiation of sleep) excluded from everyday practice, research studies and randomised clinical trials which explore effectiveness of CBT for narcolepsy and hypersomnia (e.g., Ong et al., Reference Ong, Dawson, Mundt and Moore2020). This study used single-case design so we can rigorously test the success of CBT interventions for various problem in one complex patient. Also, single-case design is useful because narcolepsy prevalence is very low in Croatia, and the main focus is on examination of available interventions, techniques, and their effects for treatment of sleep and psychological problems. The study design is ABA in nature; we took psychological and sleep measures at baseline (A), introduced CBT interventions (B), and we measured post-treatment changes (A). Dependent variables were scores on tests for depression, anxiety, sleepiness, fatigue, functional outcomes of sleep, and cataplexy frequency while the independent variable was CBT intervention.

Psychological Tests

For assessment of her problems, we used a number of reliable and validated psychological tests including the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (EPS), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), and Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ). BAI is one of the most used tests for anxiety with appropriate psychometric properties (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer1988). BAI scores range from 0 to 63 and there are four categories indicating the severity of anxiety symptoms: minimal (0–7), mild (8–15), moderate (16–25), and severe (26–63) anxiety. BDI is valid, reliable, and like BAI, its score ranges from 0 to 63 and there are four categories that mark the severity of depressive symptoms: minimal (0–13), mild (14–19), moderate (20–28), and severe (29–63) depression (Wang & Gorenstein, Reference Wang and Gorenstein2013). Both BDI and BAI have a 4-point scale with answers ranging from 0 to 3. EPS is a psychometrically validated measure and was developed to measure daytime sleepiness (DS) on a 4-point scale (0–3) with a total score range from 0 to 24 (Johns, Reference Johns1992). Scores can be classified as lower normal DS (0–5), higher normal DS (6–10), mild excessive DS (11–12), moderate excessive DS (13–15), and severe excessive DS (16–24). FSS is developed and validated as a measure of fatigue effect on daily activities and lifestyle in different diseases (Hjollund, Andersen, & Bech, Reference Hjollund, Andersen and Bech2007). FSS is based on a 7-point scale, with a minimum score of 9 and a maximum of 63. The higher the score, the higher effect of fatigue on everyday life is. FOSQ is a psychometrically validated measure for the assessment of the impact of sleepiness on everyday activities (Weaver et al., Reference Weaver, Laizner, Evans, Maislin, Chugh, Lyon and Dinges1997). The total score range is from 5 to 20, with a higher score meaning better sleep outcomes. Additionally, we used functional measures of cataplexy attacks from a daytime diary, and sleep from sleep diary. Validated self-reported psychological tests were used at the start of the treatment and 1-month post-treatment, while the frequency of cataplexy and sleep was measured on daily and weekly basis through functional measures.

Management

A.A. received seven treatments, with one treatment per week lasting 45–60 min via online application Zoom because of COVID-19 pandemic preventative measures. Her treatment included elements recommended and described by Marín Agudelo et al. (Reference Marín Agudelo, Jiménez Correa, Carlos Sierra, Pandi-Perumal and Schenck2014) and Bhattarai and Sumerall (Reference Bhattarai and Sumerall2017). Treatment included psychoeducation; sleep satiation and scheduled naps for sleepiness; stimulus satiation for cataplexy; progressive muscle relaxation; cognitive therapy for cognitive distortions regarding her hypersomnia with the help of the cognitive model; and sleep hygiene. Since she had specific problems with setting goals, taking care of and dealing with her problems, completing activities during the day because of tiredness, and dealing with emotional problems, the author added several other techniques, including the Pomodoro Technique (Kreider, Medina, & Slamka, Reference Kreider, Medina and Slamka2019), scheduling worry time (Shearer & Gordon, Reference Shearer and Gordon2006), emotional regulation training (Cameron & Jago, Reference Cameron and Jago2008), SMART goal setting training (Aghera et al., Reference Aghera, Emery, Bounds, Bush, Stansfield, Gillett and Santen2018), and education about problem-solving skills (Torabizadeh, Jalali, Moattari, & Moravej, Reference Torabizadeh, Jalali, Moattari and Moravej2018). Pomodoro Technique is a time management technique that helps patients split their tasks into several timed intervals (e.g., instead of cleaning the house for 1 h, a person can clean in four 15-minute intervals, with a break between each interval). Scheduling worry time helps patients to stop worrying throughout the day and focus on their worry at a specific time (e.g., a patient will try not to think about their worries during the day but instead set a specific time for worrying, usually lasting 15–13 min, and ignore their worries outside that interval). Emotional regulation training helps patients learn how to recognise their emotions, develop an understanding of unpleasant emotions, and manage them appropriately. Problem-solving skills teach patients how to find solutions for their problems rather than focus on problems per se. These skills help them find more alternative solutions and evaluate them objectively, especially regarding how each solution makes them feel and what other benefits are. SMART goals teach patients how to set appropriate goals that are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-based.

Since the original recommendation plan for CBT techniques in narcolepsy by Marín Agudelo et al. (Reference Marín Agudelo, Jiménez Correa, Carlos Sierra, Pandi-Perumal and Schenck2014) and Bhattarai and Sumerall (Reference Bhattarai and Sumerall2017) was not comprehensive and did not target all specific narcolepsy-caused problems in patients, the author deemed that this ‘generic’ recommendation required individual adaptation to the patient's needs. Complete individually tailored treatment structure based on earlier mentioned techniques is visible in Table 1.

Table 1. Treatment Outline per Session

During the treatment course, the patient exhibited problems with several techniques. As recommended in CBT guidelines for narcolepsy, scheduling naps was to temper two times per day for a duration of 15 min. Planning naps is a recommended technique for narcolepsy type 1 because patients usually have restorative sleep (e.g., Khan & Trotti, Reference Khan and Trotti2015). This recommendation and its adaptations (three times per day for 15 min; two times per day for 30 min) were unsuccessful. A.A. was not able to wake herself up with an alarm. She would wake up naturally after approximately 2 h of sleep, and she would still be tired but not return to a second nap. After careful consideration and monitoring of her sleeping schedule and sleeping behaviour with a diary, we agreed that she should try to sleep once per day for 1 h (rather than two or three times for 15 or 30 min) at 1:00 p.m. The decision was made because the patient slept more than 1 h during the day, usually around 1:00 p.m., so without clear clinical guidelines for this complication, we applied behavioural experimentation to find the solution. The first behavioural experiment (to sleep 1 h at 1:00 p.m.) was immediately successful in reducing her subjective tiredness, so we decided to keep that interval. She was able to wake herself up with an alarm, feeling refreshed.

Because of the restorative sleep in narcolepsy type 1, sleep satiation is also considered a beneficial intervention, comparable to planning naps (Marín Agudelo et al., Reference Marín Agudelo, Jiménez Correa, Carlos Sierra, Pandi-Perumal and Schenck2014; Khan & Trotti, Reference Khan and Trotti2015). Furthermore, she needed time to adapt the sleep satiation technique to her night sleep. We originally planned for her to sleep 12 h per night, from 10:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m., because it was visible from her sleep diary that she had been sleeping 9–12 h during the night and subjectively felt more refreshed after approximately 12 h of sleep. It took her around 4 weeks to adapt to that sleeping schedule. She resisted out of fear that the new sleep schedule would not help her and that she would lose ‘even more’ time out of her day. After reappraising that cognition for this problem and psychoeducation about its effectiveness and rationale, she started adapting to it. Complete adaptation was apparent at the start of the fourth treatment session. She subjectively reported feeling more refreshed.

Since her cataplexy was triggered with specific feelings of anxiety and stress, her stimulus satiation included 30 min of daily exposure to unwanted (anxious, stressful) thoughts and events. She did not hesitate to apply this technique, but only after listening to a careful explanation of its benefits and potential risks (e.g., intentional cataplexy attacks, anxiety attacks).

We initially tried a diaphragmatic breathing relaxation exercise, but it was ineffective for her. After 1 week, we decided that she should switch to progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), recommended by guidelines. PMR was effective, considering she felt more relaxed, less anxious, and more focused. She continued to apply this technique, but only in stressful situations, because the technique had started to lose its effect after a certain period of everyday use. Because of her high anxiety and stress levels, the initial instruction was to apply PMR twice daily (in the morning and before sleep). After 2 weeks, PMR did not make her feel any better; instead, the pressure to do it started to make it feel like a chore. That is why we decided she should only apply it when under extreme pressure or stress rather than every day. Furthermore, she had emotional and social problems because of social isolation and abusive relationships. To deal with this and the rest of the problematic aspects of her life, we applied SMART goals and problem-solving skills. Since she did not have any friends or support during the treatment, we needed to make some adaptations (e.g., writing down emotions and their cause, writing down how to deal with negative emotions and productively dealing with them, steps to find a new social support system, steps to engage her in becoming an advocate for rights of people with hypersomnia as disability, etc.).

We used GOAL setting for her to set her goals and plan her activities (e.g., the productive ways she wants to spend time with her children, when and how to clean, etc.) in order to have more free time and more time to spend with her children, rather than to spend all day cleaning out of fear social services would visit her again. We discussed and applied the cognitive model to that situation and used exposure (e.g., not cleaning one room to see that nothing terrifying will happen) to her fear of social services. A.A. reported that some techniques were crucial for her, especially when combined with psychoeducation (e.g., an explanation that constant cleaning only reinforces the idea that something terrifying will happen to her or her children if even one room is not perfectly clear). To deal with the other various problems during the day, she learned how to schedule worry time and productively solve her problems during that time (if they are solvable), rather than think about them all day and do nothing.

Results

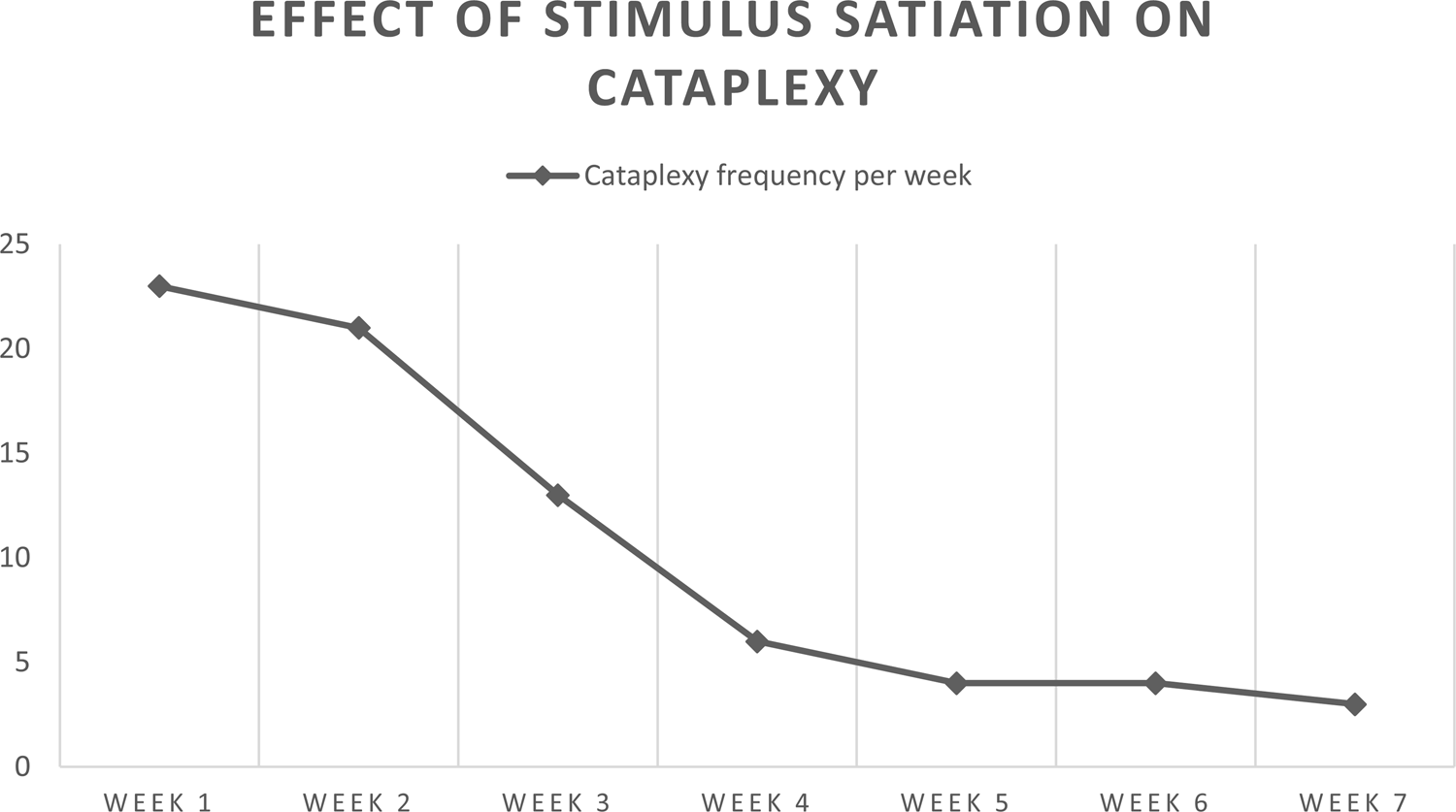

After 7 weeks, the treatment was finished, and after a 1-month follow-up, a psychological assessment was conducted to see possible improvement in psychological and sleep status. Post-treatment improvements were apparent in all areas related to anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleep problems. Pre- and post-treatment psychological measures results are visible in Table 2, with patient going from severe depression to normal range; from severe anxiety to mild; and from moderate sleepiness to mild one. To quantify the frequency of cataplexy attacks, a patient-led diary was designed specifically for that purpose. It was seen that the patient's cataplexy had been reduced significantly at the end of her treatment. Changes are visible in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Frequency of cataplexy pre- and post-treatment.

Table 2. Pre- and Post-Treatment Measures

a In this measure, higher score means greater fatigue severity, minimum score = 9, maximum score = 63.

b In this measure, higher score implies better outcomes, there are no specific norms and categories for classification.

Available standardised categories by test scores: Beck Depression Inventory: 1–10 = normal range, 11–16 = mild mood problems; 17–20 = borderline clinical depression, 21–30 = moderate depression, 31–40 = severe depression, over 40 = extreme depression. Beck Anxiety Inventory: 0–7 = minimal, 8–15 = mild anxiety, 16–25 = moderate anxiety, 26–63 = severe anxiety. Epworth Sleepiness Scale: 0–10 = normal sleepiness, 11–14 = mild sleepiness, 15–17 = moderate sleepiness, 18–24 = severe sleepiness;

Discussion and Conclusion

Any hypersomnia is a disabling condition that affects not only sleep but physical, social, emotional, and behavioural domains. Because of hypersomnia's disabling effect on the quality of life, patients can develop maladaptive behaviours, thoughts, and attitudes (Cook, Rumble, Tran, & Plante, Reference Cook, Rumble, Tran and Plante2021). Any of those dysfunctional aspects of life can be treated with CBT. This case study shows how general, science-based psychological treatments should be individually applied to a patient with narcolepsy type 1. While planning the treatment, we followed two available guidelines/recommendations for scientifically proven effective CBT techniques in hypersomnia. As expected, considering the earlier scientific data, applied techniques were effective in the reduction of several sleep problems and negative effects of sleep problems on the patient's mood. Improvements were visible on all psychological measures despite the fact that some of them, including anxiety and depression, we did not treat separately and directly. Additionally, this case study shows that a ‘general’ recommended treatment technique is not always effective for every person with a specific disorder. We saw that she did not respond appropriately to planned naps (two or three times per day, lasting 15–30 min). Instead, we designed an individual napping rhythm for her (once a day, around 1:00 p.m., for 1 h) which positively affected her.

The cognitive model was effective for recognising maladaptive behaviour, dysfunctional thoughts and attitudes, and unhealthy emotions. It is worth mentioning that because of her problems, the patient was included in CBT treatment early. She went to see a few psychologists and psychiatrists but would always quit the treatment because she did not feel it was effective. Through our seven treatment sessions, it was learned that her earlier therapists did not apply any of the techniques that were recommended by the guidelines (e.g., psychoeducation about effects of hypersomnia on her functioning, mood, self-image, etc.; progressive muscle relaxation; sleep satiation, and planned napping; stimulus satiation, etc.), except for the cognitive model. From this example, we can learn not to generalise available information about the effectiveness of specific therapeutic approaches (e.g., the idea that every version and technique from CBT is appropriate for every problem) and how to incorporate scientifically proven techniques for specific disorders in our practice. Moreover, it is always important to check if a certain technique can be applied to a patient, how they respond to it, and should we adapt it to their needs.

In addition to the self-reported measures showing improvement, the patient additionally reported subjective satisfaction with treatment and how sleep satiation, scheduled naps, stimulus satiation for cataplexy, and SMART goals were the most essential and beneficial techniques she had learned to manage life with narcolepsy type 1. Objective psychological measures showed improvement in post-test because there were several areas we had worked on which are affected by narcolepsy type 1. Earlier, the patient believed that she would feel tired for the rest of her life, but educating her about the importance of sleep and how to satiate sleep and plan naps helped her feel more refreshed. That had a positive impact on post-treatment measures for sleepiness and tiredness. Additionally, she believed that she could not have worries because they trigger cataplexy, which created a vicious cycle (she would become anxious when she had worries, and that anxiety led to cataplexy). Cataplexy satiation helped her shut down cataplexy triggers (e.g., worries, problems, traumatic thoughts) and break the vicious cycle, and techniques like SMART goals and scheduling worry helped her appropriately think about her problems, while problem-solving skills helped her think of better solutions. Progressive muscle relaxation and emotional training helped her recognise unpleasant emotions and deal with them accordingly. We can conclude that pre- and post-treatment changes in test results are probably due to the positive cumulative effect of CBT interventions adapted for narcolepsy type 1.

CBT treatment designed for narcolepsy type 1 appears to be effective even when a patient has a history of psychiatric disorders, traumatic experiences, problems in psychosocial functioning, comorbid sleep disorders, and other psychological problems. This case study shows the importance of incorporating clinical guidelines in everyday clinical practice, as well as the importance of individualising treatment to the patients’ needs. This work highlights the importance of the therapist–patient bond and its importance for a therapeutic alliance. If they work with especially vulnerable clinical populations, psychologists and therapists need to be willing to adapt the treatment to the patients’ needs and capabilities. Also, it is important to respect the patients’ boundaries. Despite being offered to work on her trauma later in treatment (after narcolepsy type 1 has been treated), the patient refused, and the therapist respected her decision.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The author declared none.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.