Introduction

Employees who ruminate about the possibility of quitting their jobs are a significant source of concern for organizations, because they focus less on contributing to organizational well-being and instead dedicate their time and effort to improving their current situation or searching for other job opportunities (Jiang, Wang, Chu, & Zheng, Reference Jiang, Wang, Chu and Zheng2019; Mai, Ellis, Christian, & Porter, Reference Mai, Ellis, Christian and Porter2016). They also may create substantial financial costs, particularly if they actually leave, because of the investments the firms must make to select, socialize, and train replacements (Cascio, Reference Cascio1991; Gallagher & Nadarajah, Reference Gallagher and Nadarajah2004; Joo, Hahn, & Peterson, Reference Joo, Hahn and Peterson2015; Tews, Michel, & Ellingson, Reference Tews, Michel and Ellingson2013). Moreover, making plans to quit may be detrimental to the employees themselves, who likely experience stress when considering whether to leave a familiar organization and take the risk of pursuing a new job (Dowden & Tellier, Reference Dowden and Tellier2004; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Plummer, Lam, Wang, Cross and Zhang2019). Finally, employees' further career development may be compromised if their turnover intentions are exposed but limited alternative job opportunities prevent them from actually switching organizations (Khatri, Fern, & Budhwar, Reference Khatri, Fern and Budhwar2001; Mano-Negrin & Tzafrir, Reference Mano-Negrin and Tzafrir2004).

In light of these challenges, we seek to understand why employees still might consider quitting their jobs and even devote substantial energy to these thoughts. A plethora of factors could spur employees' turnover intentions, such as negative perceptions about pay (Guan et al., Reference Guan, Wen, Chen, Liu, Si, Liu and Dong2014), limited decision autonomy (Dysvik & Kuvaas, Reference Dysvik and Kuvaas2013), stress-inducing organizational change (Rafferty & Restubog, Reference Rafferty and Restubog2017), workplace bullying (Lutgen-Sandvik, Hood, & Jacobson, Reference Lutgen-Sandvik, Hood and Jacobson2016), or a lack of mentoring support (Park, Newman, Zhang, Wu, & Hooke, Reference Park, Newman, Zhang, Wu and Hooke2016). A common theme among these antecedents is that employees feel unhappy about some negative treatment they receive from their organization or its constituents (Lawong, McAllister, Ferris, & Hochwarter, Reference Lawong, McAllister, Ferris and Hochwarter2018; Wiltshire, Bourdage, & Lee, Reference Wiltshire, Bourdage and Lee2014). Another source of frustration at work might arise from organizational colleagues who engage in dysfunctional political behaviors (Johnson, Rogers, Stewart, David, & Witt, Reference Johnson, Rogers, Stewart, David and Witt2017; Kacmar & Baron, Reference Kacmar, Baron and Ferris1999), think only about themselves instead of what is best for the company, and work behind the scenes to improve their own situation, irrespective of the consequences for others (Hochwarter, Kacmar, Perrewé, & Johnson, Reference Hochwarter, Kacmar, Perrewé and Johnson2003). Such dysfunctional politics are an unfortunate reality in many organizations, and the persistent detrimental effects for organizational and individual well-being makes it a critical issue that requires on-going investigations in various contexts, including non-Western ones (Jam, Donia, Raja, & Ling, Reference Jam, Donia, Raja and Ling2017; Khan, Khan, & Gul, Reference Khan, Khan and Gul2019; Valle, Kacmar, & Zivnuska, Reference Valle, Kacmar and Zivnuska2019).

The perception that organizational colleagues are overly political in their actions can be very upsetting for employees, because it threatens to compromise the quality of their current and future organizational functioning (Abbas, Raja, Darr, & Bouckenooghe, Reference Abbas, Raja, Darr and Bouckenooghe2014; Brouer, Harris, & Kacmar, Reference Brouer, Harris and Kacmar2011). Prior research cites a broad range of harmful outcomes of perceived organizational politics, including enhanced job stress (Jam et al., Reference Jam, Donia, Raja and Ling2017), absenteeism (Vigoda-Gadot & Meisler, Reference Vigoda-Gadot and Meisler2010), and counterproductive work behaviors (Cohen & Diamant, Reference Cohen and Diamant2019). It also points to the diminished likelihood of positive outcomes, such as organizational citizenship behavior (De Clercq & Belausteguigoitia, Reference De Clercq and Belausteguigoitia2017), proactive performance (Varela-Neira, Araujo, & Sanmartin, Reference Varela-Neira, Araujo and Sanmartin2018), job satisfaction (Valle & Witt, Reference Valle and Witt2001), and commitment to change (Bouckenooghe, Reference Bouckenooghe2012). Moreover, extant research points to a positive relationship of perceived organizational politics with turnover intentions (e.g., Abbas et al., Reference Abbas, Raja, Darr and Bouckenooghe2014; Miller, Adair, Nicols, & Smart, Reference Miller, Adair, Nicols and Smart2014; Poon, Reference Poon2003), which might stem from mediating factors such as burnout (Huang, Chuang, & Lin, Reference Huang, Chuang and Lin2003), strain (Chang, Rosen, & Levy, Reference Chang, Rosen and Levy2009), insufficient perceived organizational support (Harris, Harris, & Harvey, Reference Harris, Harris and Harvey2007), work engagement (Agarwal, Reference Agarwal2016), or morale (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Rosen and Levy2009).

To complement this research stream, we investigate another, unexplored, behavioral factor that may inform the relationship between employees' beliefs about others' self-serving behaviors and their own turnover intentions, namely, their reluctance to adapt to the behaviors displayed by their colleagues (Griffin & Hesketh, Reference Griffin and Hesketh2003; Gwinner, Bitner, Brown, & Kumar, Reference Gwinner, Bitner, Brown and Kumar2005). In particular, beliefs about dysfunctional political games might spur employees' desire to leave, because they are unwilling to adjust to this negative work situation and do not find such political games justifiable (Wu, Tian, Luksyte, & Spitzmueller, Reference Wu, Tian, Luksyte and Spitzmueller2017). This process could be buffered though by employees' emotional regulation skills—a personal resource that enables them to control their negative feelings in the presence of others' self-centered actions (Jiang, Zhang, & Tjosvold, Reference Jiang, Zhang and Tjosvold2013)—such that the risk that they become further isolated from the rest of the organization decreases, with positive consequences for their propensity to stay with the organization.

In theorizing and testing these links, we seek to make several contributions. First, we predict and empirically demonstrate the role of a relevant but overlooked mediator between perceptions of organizational politics and turnover intentions: employees' refusal to understand or adapt to other organizational members (Baron & Markman, Reference Baron and Markman2003; Pulakos, Arad, Donovan, & Plamondon, Reference Pulakos, Arad, Donovan and Plamondon2000). Beliefs about the self-serving nature of other members' behaviors may enhance employees' propensity to leave, because they refuse to compromise with or accommodate the preferences of these members. Deep frustration about how colleagues exploit opportunities with organizational decision makers, to advance their own position at the expense of others, may cause employees to seek revenge, avoid further interactions with these colleagues, and reject any justifications for their egoistic behaviors (Chang, Rosen, Siemieniec, & Johnson, Reference Chang, Rosen, Siemieniec and Johnson2012; De Clercq & Belausteguigoitia, Reference De Clercq and Belausteguigoitia2017). Such behavioral responses then might escalate into a strong desire to leave the organization, prompting them to make concrete plans to quit (Campbell, Perry, Maertz, Allen, & Griffeth, Reference Campbell, Perry, Maertz, Allen and Griffeth2013).

Second, we detail when the escalation of perceived organizational politics into enhanced turnover intentions, due to employees' refusal to engage in social adaptive behavior, might be less likely to materialize, because those employees can draw from their emotional regulation skills (Deng, Walter, Lam, & Zhao, Reference Deng, Walter, Lam and Zhao2017; Parke, Seo, & Sherf, Reference Parke, Seo and Sherf2015). Previous studies have explained how other personal resources increase employees' ability to cope with dysfunctional organizational politics, like their psychological capital (Abbas et al., Reference Abbas, Raja, Darr and Bouckenooghe2014), resilience (De Clercq & Belausteguigoitia, Reference De Clercq and Belausteguigoitia2017), locus of control (Agarwal, Reference Agarwal2016), or work experience (Varela-Neira et al., Reference Varela-Neira, Araujo and Sanmartin2018). Furthermore, by examining the buffering role of emotional regulation skills, we add insights to studies on how emotion-based competencies can mitigate the challenges that come with other resource-draining work conditions, such as job insecurity (Cheng, Huang, Lee, & Ren, Reference Cheng, Huang, Lee and Ren2012), conflict (Hagemeister & Volmer, Reference Hagemeister and Volmer2018), or disruptive leadership (Hou, Li, & Yuan, Reference Hou, Li and Yuan2018). With our approach, we thus inform organizations that they can protect themselves against the harmful influences of politically oriented decision making within their ranks if they select and retain employees who approach difficult work situations rationally instead of emotionally, such that they are less likely to consider quitting.

Third, the empirical context of this study is Pakistan, which represents a response to calls to examine the negative outcomes of politicized organizational decision-making processes in non-Western settings (Agarwal, Reference Agarwal2016; Bai, Han, & Harms, Reference Bai, Han and Harms2016; De Clercq, Haq, & Azeem, Reference De Clercq, Haq and Azeem2019). In this country setting, cultural factors may exert two pertinent but contrasting influences on the focal phenomena. On the one hand, the high levels of uncertainty avoidance that mark Pakistani culture (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, Reference Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov2010; Syed & Malik, Reference Syed and Malik2014) may lead employees to experience risk-inducing political decision making as especially stressful, such that they react with maladaptive behaviors and a greater desire to quit. On the other hand, the high levels of collectivism in Pakistan (Aycan, Schyns, Sun, Felfe, & Saher, Reference Aycan, Schyns, Sun, Felfe and Saher2013; Hofstede et al., Reference Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov2010) may mean that reactions that threaten to undermine group harmony or signal organizational betrayal are normatively unacceptable, so employees might avoid them, even in the presence of dysfunctional organizational politics. From this perspective, Pakistan offers an interesting context to investigate how employees deal with their own beliefs about dysfunctional organizational politics, as well as the roles of their emotional regulation skills in this process.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Employees' turnover intentions likely lead to actual decisions to leave (Chen, Lin, & Lien, Reference Chen, Lin and Lien2011; Mulki, Jaramillo, & Locander, Reference Mulki, Jaramillo and Locander2008), but many researchers prefer to address why employees differ in their turnover intentions, instead of actual turnover. The act of quitting can be strongly influenced by factors external to the organization, such as the surrounding economic climate or the availability of other job opportunities (Amankwaa & Anku-Tsede, Reference Amankwaa and Anku-Tsede2015; Mano-Negrin & Tzafrir, Reference Mano-Negrin and Tzafrir2004). To help organizations design their internal features to reduce turnaround, it thus is highly relevant to explain turnover intentions. For example, by explicating how and why employees react negatively to dysfunctional politics in organizational decision making, as manifest in persistent egoistic, self-centered behaviors by organizational colleagues (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Adair, Nicols and Smart2014), we can provide relevant insights for many organizations, especially those that operate in competitive labor markets in which the loss of skilled employees is particularly problematic (Tews et al., Reference Tews, Michel and Ellingson2013; Thatcher, Stepina, & Boyle, Reference Thatcher, Stepina and Boyle2003).

We start by theorizing that a reluctance to engage in social adaptive behavior may be a critical path by which employees seek to maintain their sense of self-worth and avoid frustrations that result from encountering others' self-centered tendencies (Grimland, Vigoda-Gadot, & Baruch, Reference Grimland, Vigoda-Gadot and Baruch2012; Siu, Lu, & Spector, Reference Siu, Lu and Spector2013). In considering this function of reduced social adaptive behavior, we complement research on how this behavior affects employee–customer relationships (Leischnig & Kasper-Brauer, Reference Leischnig and Kasper-Brauer2015; Wilder, Collier, & Barnes, Reference Wilder, Collier and Barnes2014) or determines employees' reactions to organizational change (van den Heuvel, Demerouti, Bakker, & Schaufeli, Reference van den Heuvel, Demerouti, Bakker and Schaufeli2013; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tian, Luksyte and Spitzmueller2017). Dysfunctional organizational decision-making processes tend to undermine employees' self-esteem and confidence (Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall, & Alarcon, Reference Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall and Alarcon2010; Pierce & Gardner, Reference Pierce and Gardner2004). By refusing to engage in social adaptive behavior, employees leverage a behavioral mechanism to cope with organizational politics and preserve their self-esteem. As prior research indicates, employees' withdrawal behaviors are important means through which employees seek to vent deep-felt frustrations about resource-depleting work circumstances (Penney & Spector, Reference Penney and Spector2005; Sliter, Sliter, & Jex, Reference Sliter, Sliter and Jex2012). Thus, beliefs about the self-serving actions of organizational colleagues similarly may translate into higher turnover intentions because employees respond to the negative work situation by striking back and refusing to adapt to or become more like their colleagues (Gwinner et al., Reference Gwinner, Bitner, Brown and Kumar2005; Rosen, Koopman, Gabriel, & Johnson, Reference Rosen, Koopman, Gabriel and Johnson2016). That is, such negative reactions likely prompt employees to withdraw psychologically from their organization and its constituents, so that quitting their jobs becomes a more attractive option (Carpenter & Berry, Reference Carpenter and Berry2017).

This escalation of perceived organizational politics into enhanced turnover intentions, due to a reluctance to adapt to the behaviors of organizational colleagues, also may be more or less likely to occur in certain scenarios. We propose that an ability to remain calm, even in the face of adverse work situations, can mitigate the harmful effects of employees' beliefs about organizational politics on their social adaptive behavior (Buruck, Dörfel, Kugler, & Brom, Reference Buruck, Dörfel, Kugler and Brom2016; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Huang, Lee and Ren2012), so their desire to leave is lower. When they possess this personal resource, employees can assess their colleagues' self-serving behaviors rationally (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Zhang and Tjosvold2013), such that they might even identify reasons their colleagues behave so egoistically (Takada & Ohbuchi, Reference Takada and Ohbuchi2013). By detailing this buffering role of emotional regulation skills, we respond to calls for contingency views on the negative outcomes of perceived organizational politics (Maslyn, Farmer, & Bettenhausen, Reference Maslyn, Farmer and Bettenhausen2017; Valle et al., Reference Valle, Kacmar and Zivnuska2019; Varela-Neira et al., Reference Varela-Neira, Araujo and Sanmartin2018), including considerations of employees' emotion-based competencies (Vigoda-Gadot & Meisler, Reference Vigoda-Gadot and Meisler2010).

Conservation of resources theory

To guide these theoretical arguments, we draw on conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989) According to this theory, employees' work attitudes and behaviors are informed by their desire to conserve their existing resource bases and shield themselves against further resource losses (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989, Reference Hobfoll2001). In particular, by engaging in harmful work behaviors, employees who suffer from adverse work circumstances can overcome the frustrations they experience (De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, Haq and Azeem2019; Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu, & Westman, Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). If employees are convinced their organizational colleagues work behind the scenes and engage in self-serving behaviors, they may suffer from resource losses, in the form of reduced self-esteem, because these behaviors tend to threaten their own professional well-being and career success (Grimland et al., Reference Grimland, Vigoda-Gadot and Baruch2012; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Harris and Harvey2007). They, in turn, may seek to maintain a sense of self-worth, even in a disappointing, unfavorable situation (Penney, Hunter, & Perry, Reference Penney, Hunter and Perry2011), by refusing to adapt to the whims of their colleagues. This behavioral response helps employees contain self-depreciating thoughts, though COR theory also suggests that the psychological withdrawal that they experience from their organizational members (Carpenter & Berry, Reference Carpenter and Berry2017) may then fuel their desire not to devote valuable energy resources to enhance the well-being of their current employer. The overall result ultimately might be higher turnover intentions (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Perry, Maertz, Allen and Griffeth2013).

Moreover, employees' negative reactions to adverse, resource-depleting work conditions also depend on their access to relevant personal resources (Abbas et al., Reference Abbas, Raja, Darr and Bouckenooghe2014; Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). From this COR view, employees' emotional regulation skills may serve as buffers that mitigate their refusal to exhibit social adaptive behaviors in response to perceived organizational politics, which ultimately reduces their desire to quit. If employees can control their temper and avoid becoming angry, even in difficult situations (Hagemeister & Volmer, Reference Hagemeister and Volmer2018; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Zhang and Tjosvold2013), they should be more willing to adapt and align with organizational colleagues who exhibit highly political actions. Formally, when they can draw from emotional competencies, the translation of employees' experience of resource-draining dysfunctional politics into turnover intentions, through social adaptive behavior, should be subdued (Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000).

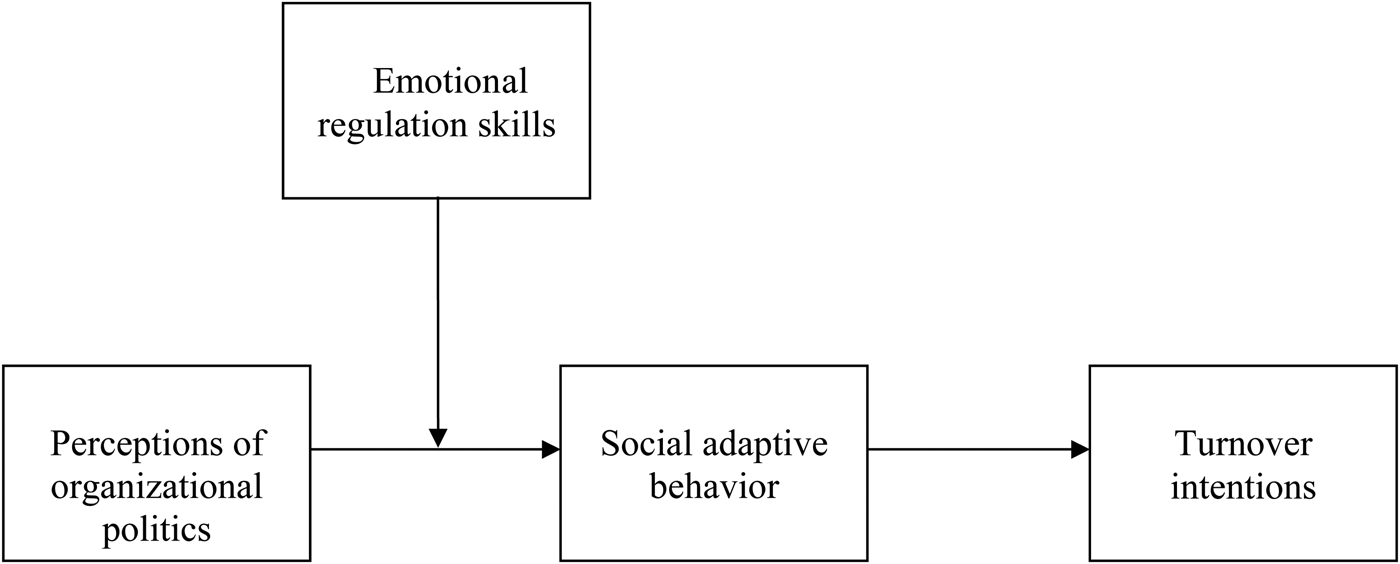

The proposed conceptual framework is in Figure 1. Persistent beliefs that organizational colleagues are overly political in their actions spur employees' turnover intentions, in their effort to preserve their self-esteem by refusing to adapt to their colleagues. Their emotional regulation skills function as buffers; the escalation of perceived organizational politics into enhanced turnover intentions, through reduced social adaptive behavior, becomes less likely when employees can stay calm, instead of getting angry, in the face of a negative work situation.

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

Mediating role of social adaptive behavior

According to COR theory, employees' work behaviors are strongly shaped by their motivation to preserve their resource reservoirs and diminish the chances of resource drainage, even if they might confront adverse work circumstances (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989, Reference Hobfoll2001). As mentioned, this theory further conceives of employees' negative behavioral responses to workplace adversity as tactics they use to release their frustrations with adversity and protect their self-esteem resources (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). For example, undertaking deviant work activities is a coping mechanism that employees, overburdened with unrealistic deadlines, use to take revenge and vent their associated frustrations (De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, Haq and Azeem2019). We argue that employees' beliefs that organizational colleagues are egoistic and self-centered similarly may prompt them to ignore their colleagues, refusing to adapt to their preferences, which gives them an outlet for their negative energy (Cohen & Diamant, Reference Cohen and Diamant2019; Penney, Spector, & Fox, Reference Penney, Spector, Fox, Sagie, Koslowsky and Stashevsky2003).

Employees who feel disheartened by the political games that their organizational colleagues play also may interpret this behavior as a lack of respect for their own professional well-being (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Harris and Harvey2007; Jam et al., Reference Jam, Donia, Raja and Ling2017), which generates concerns about their ability to meet their performance requirements (Rosen, Harris, & Kacmar, Reference Rosen, Harris and Kacmar2011; Siu et al., Reference Siu, Lu and Spector2013) and develop their career successfully (Grimland et al., Reference Grimland, Vigoda-Gadot and Baruch2012). In turn, those employees may seek to avoid additional resource losses and preserve their self-esteem by expressing disappointment and rejecting the preferences or actions of their colleagues (Bentein, Guerrero, Jourdain, & Chênevert, Reference Bentein, Guerrero, Jourdain and Chênevert2017; Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). That is, employees might justify their own maladaptive behaviors by noting the lack of support they receive from their organization and its constituents, who only think about themselves (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Harris and Harvey2007). A refusal to adapt to colleagues' actions represents a pertinent response that helps employees feel better about themselves, because it is a signal or expression of their irritation with the negative situation (Sliter et al., Reference Sliter, Sliter and Jex2012). Finally, employees who are convinced that their colleagues work to advance their own interests, at the expense of others, may respond with reduced efforts to adapt, so that they might regain some control over their work functioning and not to be seen as ‘easy’ to exploit or weak (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Koopman, Gabriel and Johnson2016).

Yet the social isolation that employees experience due to their maladaptive behaviors may, in turn, create a negative spiral, such that they feel even more negative feelings toward their organization and a growing desire to quit their jobs. In particular, COR theory postulates that the social distancing that stems from a reluctance to adapt to other organizational members (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tian, Luksyte and Spitzmueller2017) may enhance employees' turnover intentions, because they are not willing to allocate valuable energy resources to activities that otherwise would benefit their employer and its members (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Perry, Maertz, Allen and Griffeth2013; Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000). Instead, their focus is redirected toward how they can improve their own personal situation, such as the benefits they might enjoy if they were to leave their current employment (Bozeman & Perrewé, Reference Bozeman and Perrewé2001). Furthermore, a refusal to accommodate others' behaviors also may generate expectations of retaliation, so the focal employee might anticipate being unable to count at all on any consideration and support (Scott, Restubog, & Zagenczyk, Reference Scott, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013). The prospect of alternative employment thus becomes highly attractive. Finally, when employees distance themselves from colleagues, it likely creates a lack of emotional attachment toward the surrounding work environment, which may stimulate their desire to leave the current organization (Chen & Yu, Reference Chen and Yu2014).

These arguments suggest a mediating role of social adaptive behavior: Employees' beliefs about self-serving behaviors by colleagues increase their turnover intentions, because they refuse to go out of their way to understand the reasons for those behaviors or adjust themselves to them (Gwinner et al., Reference Gwinner, Bitner, Brown and Kumar2005; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Tian, Luksyte and Spitzmueller2017). Prior studies similarly indicate a mediating role of surface acting (Andrews, Kacmar, & Valle, Reference Andrews, Kacmar and Valle2016) between perceived organizational politics and turnover intentions. We extend such research by explicating how employees' beliefs that colleagues play dysfunctional political games make them want to quit, prompted by another behavioral response, by which they refrain from social adaptive behavior.

Hypothesis 1: Employees' diminished social adaptive behavior mediates between their perceptions of organizational politics and turnover intentions.

Moderating role of emotional regulation skills

We hypothesize a moderating effect of employees' emotional regulation skills on the indirect positive relationship between their perception of organizational politics and turnover intentions through social adaptive behavior. Emotionally skilled employees should react to these politics with more social adaptive behavior. The premises of COR theory state that the resource-draining effect of adverse organizational conditions is mitigated to the extent that employees can counter resource losses with access to valuable personal resources (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001). If employees can easily control their emotions, they are well positioned to cope with the difficulties of dysfunctional political games, because they can manage and contain the negative energy that arises in response to such organizational adversity (Ashkanasy, Reference Ashkanasy2002; Buruck et al., Reference Buruck, Dörfel, Kugler and Brom2016; Gross, Reference Gross1998; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Zhang and Tjosvold2013). This increased coping capability diminishes their frustration with colleagues and need to release it (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). Prior research similarly notes that employees who are emotionally skilled can shield themselves from the negative consequences of other resource-draining work conditions, such as excessive work conflict (Hagemeister & Volmer, Reference Hagemeister and Volmer2018) or perceived contract breaches (De Clercq & Belausteguigoitia, Reference De Clercq and Belausteguigoitia2020).

Employees who can control their own emotions also are better able to take others' perspective (Parke et al., Reference Parke, Seo and Sherf2015; Qian et al., Reference Qian, Han, Guo, Yang, Wang and Wang2016) and empathize with why organizational colleagues might behave in self-serving ways. These employees even may find it appealing to encounter challenging situations, because their ability to adapt and approach the situation rationally can generate a sense of personal accomplishment (Biron & van Veldhoven, Reference Biron and van Veldhoven2012; Sy, Tram, & O'Hara, Reference Sy, Tram and O'Hara2006). In this way, emotional regulation skills may help employees deal with the challenges of others' egoistic actions, as well as generate self-satisfaction, because they are able to protect themselves against the hardships that arise with these actions (Meisler, Reference Meisler2014; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000). Similarly, emotionally skilled employees may see the presence of dysfunctional political games as opportunities to showcase their ability to deal with and adapt to the games (Vigoda-Gadot & Meisler, Reference Vigoda-Gadot and Meisler2010). In contrast, employees who do not have a good grasp on their own emotions may use dysfunctional politics as an excuse to distance themselves and become more rigid in their interactions (Hagemeister & Volmer, Reference Hagemeister and Volmer2018). These employees who lack the ability to regulate their emotions then may be more likely to vent the stress they feel by refusing to adapt to the preferences of these others (Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000; Penney & Spector, Reference Penney and Spector2005).

The combination of these arguments, along with the mediating role of social adaptive behavior, indicates a moderated mediation dynamic (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007). In particular, employees' emotional regulation skills may serve as critical contingencies of the indirect effect of perceived organizational politics on turnover intentions, through social adaptive behavior. For emotionally skilled employees, the role of diminished social adaptive behavior is weaker, whereas the tendency not to adapt to organizational colleagues likely grows stronger when employees lack strong emotional regulation skills, in which case their frustrations about others' resource-draining, self-serving behaviors are more likely to translate into a desire to quit (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018). When employees get easily angry, their diminished social adaptive behavior offers a more critical explanation of how their perceptions of organizational politics enhance their intentions to leave.

Hypothesis 2: The indirect relationship between employees' perceptions of organizational politics and turnover intentions through diminished social adaptive behavior is moderated by their emotional regulation skills, such that this indirect relationship is weaker among employees with greater emotional regulation skills.

Research method

Sample and data collection

The research hypotheses were tested with survey data collected among three Pakistani-based organizations that operate in the food sector. This purposeful focus on one sector avoids the problem of unobserved, industry-related differences in employees' turnover intentions, which may depend on the extent to which alternative employment opportunities are readily available in an industry (Acikgoz, Sumer, & Sumer, Reference Acikgoz, Sumer and Sumer2016; Virga, De Witte, & Cifre, Reference Virga, De Witte and Cifre2017). The food sector in Pakistan is marked by high levels of competition and unemployment (Bhutta & Hasan, Reference Bhutta and Hasan2013; Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2020), so it is generally challenging for employees to find another job in this industry, if they were to leave their current employment. From this angle, our study offers a conservative test of the connection between employees' perceptions of organizational politics and turnover intentions, through diminished social adaptive behavior (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010). That is, if the empirical findings confirm the hypothesized relationships even in this job-constraining context, it is plausible that the relationships would be even more salient in contexts that provide ample alternative employment opportunities (Baranchenko, Xie, Lin, Lau, & Ma, Reference Baranchenko, Xie, Lin, Lau and Ma2020; Mano-Negrin & Tzafrir, Reference Mano-Negrin and Tzafrir2004).

The three-wave survey design included three data collection rounds, each separated by three weeks, to avoid concerns about reverse causality (i.e., employees' social adaptive behaviors arguably might generate positive perceptions about the organizational functioning of their colleagues, or their turnover intentions might make them unwilling to adjust to the constituents of an organization that they plan to leave). This design also reduced the chances of expectancy bias, whereby employees might figure out the research hypotheses and adjust their responses accordingly. Yet the time gaps of three weeks were short enough to minimize the risk that critical organizational events could have occurred during the data collection. The surveys were written in English, which is the language of business communication in Pakistan.

Several methods helped protect the rights of the participants and also avoid social desirability bias. In particular, the cover letters that preceded the surveys guaranteed complete confidentiality for the respondents, underscored that their participation was entirely voluntary, and indicated that they could withdraw from the study at any point in time. Participants were also explicitly told that there were no correct or incorrect answers and that the responses to the different questions likely would vary across participants (Spector, Reference Spector2006). The first survey gauged employees' perceptions of organizational politics and emotional regulation skills, the second survey captured their engagement in social adaptive behaviors, and the third assessed their turnover intentions. Of the 250 originally administered surveys, we received 160 completed sets across the three rounds, for a response rate of 64%. Among the respondents, 27% were women. They had worked for their organization for an average of six years.

Measures

Perceptions of organizational politics

Employees' beliefs that their organizational colleagues are self-centered in their actions were assessed with a four-item scale of perceived organizational politics, pertaining to how employees perceive the actions of their colleagues (De Clercq & Belausteguigoitia, Reference De Clercq and Belausteguigoitia2017). Two sample items are, ‘There is a lot of self-serving behavior going on among my organizational colleagues’ and ‘My organizational colleagues do what is best for them, not what is best for the company’ (Cronbach's alpha = .94).

Emotional regulation skills

We assessed employees' ability to regulate their own emotions with a four-item scale derived from prior research on emotional competencies (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Zhang and Tjosvold2013). Example items are, ‘I am quite capable of controlling my own emotions’ and ‘I am able to control my temper so that I can handle difficulties rationally’ (Cronbach's alpha = .89).

Social adaptive behavior

To measure the extent to which employees are willing to adjust to organizational colleagues, we adapted a five-item scale of social adaptation skills (Baron & Markman, Reference Baron and Markman2003). In particular, in light of our focus on employees' behavioral reactions to organizational politics, the revised wording reflected their actual behavior. For example, participants indicated the extent to which, ‘I adjust myself to the preferences of organizational colleagues’ and ‘I am sensitive and understanding toward organizational colleagues’ (Cronbach's alpha = .91).

Turnover intentions

Employees' desire to leave their current employment was assessed with a five-item scale of turnover intentions (Bozeman & Perrewé, Reference Bozeman and Perrewé2001). Two of these measurement items are, ‘I will probably look for a new job in the near future’ and ‘I intend to quit my job soon’ (Cronbach's alpha = .78).

Control variables

The statistical analyses controlled for three variables: employees' gender (1 = female), education level (1 = high school, 2 = non-university college, 3 = university bachelor, 4 = university masters), and organizational tenure (in years). Female employees, as well as higher-educated employees and those who have worked for their organization for a longer time, may be more loyal (Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, Reference Griffeth, Hom and Gaertner2000).Footnote 1

Construct validity

The validity of the focal constructs was evaluated with a confirmatory factor analysis of a four-factor measurement model (Anderson & Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988). The fit of the model was good: χ2(129) = 314.02, incremental fit index = .91,Tucker−Lewis index = .89, confirmatory fit index = .91, and root mean-squared error of approximation = .09. In support of the presence of convergent validity, each of the measurement items loaded well (p < .001) on its corresponding constructs (Gerbing & Anderson, Reference Gerbing and Anderson1988). The average variance extracted (AVE) values were higher than the cut-off value of .50 (Bagozzi & Yi, Reference Bagozzi and Yi1988), except for turnover intentions, for which the AVE value equaled .43.Footnote 2 The presence of discriminant validity was evident too, in that for all four focal constructs, the AVE values were higher than the squared correlations of the corresponding construct pairs (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). The fit of models that included unconstrained construct pairs, in which the correlation between two constructs was set free, also was significantly better than the fit of the corresponding constrained models, in which the correlation between two constructs was set to equal 1 (Δχ2(1) > 3.84, p < .05; Anderson & Gerbing, Reference Anderson and Gerbing1988).

Statistical procedure

The research hypotheses were tested with the SPSS Process macro, as developed by Hayes (Reference Hayes2013). This macro supports the comprehensive evaluation of theoretical frameworks that include mediation and moderated mediation effects, as illustrated by previous studies (e.g., Skiba & Wildman, Reference Skiba and Wildman2019; Wang, Bowling, Tian, Alarcon, & Kwan, Reference Wang, Bowling, Tian, Alarcon and Kwan2018). The Process macro approach is preferred over other methods—such as the Sobel (Reference Sobel and Leinhardt1982) test or the method described by Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986)—because it does not make the assumption that the indirect effects (mediation) and conditional indirect effects (moderated mediation) are normally distributed. In particular, it acknowledges that the sampling distributions of the mediation and moderated mediation effects may be asymmetric, and it accordingly relies on a bootstrapping procedure (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, Reference MacKinnon, Lockwood and Williams2004).

First, to assess the presence of mediation (Hypothesis 1), we evaluated the confidence interval for the indirect effect of perceptions of organizational politics on turnover intentions, through social adaptive behavior. In this first step, we also checked the signs and significance levels of the underlying direct relationships between perceived organizational politics and social adaptive behavior and between social adaptive behavior and turnover intentions. Second, to assess the presence of moderated mediation (Hypothesis 2), we evaluated the confidence intervals for the conditional indirect effects. The Process macro estimates confidence intervals at three distinct levels of the moderator: one standard deviation below its mean, at its mean, and one standard deviation above its mean.Footnote 3 In this second step, we also assessed the moderating effect of emotional regulation skills on the relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and social adaptive behavior, by comparing the corresponding effect sizes. To diminish the risk of multicollinearity, we mean-centered the variables before including them in the interaction term (Aiken & West, Reference Aiken and West1991).

Results

Table 1 reports the zero-order correlation coefficients and descriptive statistics, and Table 2 reports the results generated from the Process macro. Perceptions of organizational politics diminish social adaptive behavior (β = −.613, p < .01), which then leads to higher turnover intentions (β = −.218, p < .01). The test for the presence of mediation indicates an effect size of .068 for the indirect relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and turnover intentions through social adaptive behavior. This relationship is significant, because the corresponding confidence interval does not include 0 [.015, .127], in support of the hypothesized mediating role by social adaptive behavior.

Table 1. Correlation table and descriptive statistics

Notes: N = 160.

* p < .05; ** p < .01.

Table 2. Process macro results for individual paths

Notes: n = 160.

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

The evaluation of Hypothesis 2 entails a comparison of the strength of the conditional indirect effect of perceptions of organizational politics on turnover intentions through social adaptive behavior at different levels of emotional regulation skills. The results reveal weaker effect sizes at higher skill levels: from .093 at one standard deviation below the mean, to .086 at the mean, to .025 at one standard deviation above the mean (Table 3). In addition, the confidence interval does not include 0 when the moderator is at one standard deviation below its mean ([.025; .172]) or at its mean ([.023; .161]), but it includes 0 when the mediator is at one standard deviation above the mean ([−.001; .088]). To test for the presence of moderated mediation in a more direct way, we also assessed the index of moderated mediation and its associated confidence interval (Hayes, Reference Hayes2015). The index equals −.027, and its confidence interval does not include 0 ([−.055; −.004]), which affirms that employees' emotional regulation skills function as buffers against the translation of perceived organizational politics into turnover intentions through social adaptive behavior, in line with Hypothesis 2.

Table 3. Conditional indirect effects and index of moderated mediation

Notes: n = 160; SD = standard deviation; SE = standard error; LLCI = lower limit confidence interval; ULCI = upper limit confidence interval.

Finally, Table 2 indicates a positive, significant effect of the perceptions of organizational politics × emotional regulation skills interaction term (β = .125, p < .01) in predicting social adaptive behavior. The results generated from the Process macro show that the direct negative relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and social adaptive behavior is mitigated by emotional regulation skills, as manifest in the lower effect sizes of this relationship at higher levels of the moderator (i.e., −.426 at one standard deviation below the mean, −.395 at the mean, −.114 at one standard deviation above the mean).

Discussion

This research adds to extant literature by investigating the role of employees' beliefs about the self-serving behaviors of their colleagues in predicting their own turnover intentions, with special consideration of unexplored factors that explain or influence this process. Exposure to dysfunctional political games can trigger employees to make plans to quit their jobs, yet very little attention has been devoted to the behavioral reactions that may underpin this process—except for a study that pinpoints the role of surface acting behavior (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Kacmar and Valle2016)—let alone the potential buffering influence of their reliance on pertinent personal skills. Consistent with the logic of COR theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001), we theorize that (1) turnover intentions may arise in the presence of dysfunctional organizational politics because employees are reluctant to adapt themselves to the actions of their organizational colleagues, in their bid to conserve their self-esteem resources (Bentein et al., Reference Bentein, Guerrero, Jourdain and Chênevert2017; Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1989), and (2) their emotional regulation skills mitigate this effect (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Zhang and Tjosvold2013). The empirical results support these conceptual arguments.

The mediating role of diminished social adaptive behavior, as revealed in this study, elucidates how employees who encounter others' self-serving actions develop a strong desire to leave their organization, because they distance themselves from the rest of the organization, as manifest in their reluctance to accommodate the preferences of other members and understand their motivations (Gwinner et al., Reference Gwinner, Bitner, Brown and Kumar2005). These employees may interpret others' egoistic behaviors as a lack of consideration of their own diligent work efforts, which undermines their sense of self-worth in relation to their organizational functioning (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Eschleman, Wang, Kirkendall and Alarcon2010). Consistent with the COR logic, they seek to maintain their self-esteem resources by releasing their frustration with their colleagues, in the form of a refusal to adapt to their preferences (De Clercq et al., Reference De Clercq, Haq and Azeem2019; Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000). Similarly, they might become cynical about the lack of organizational protection they receive from the self-serving actions of other members, such that they are convinced that their maladaptive behavioral responses are justified (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Chuang and Lin2003). Yet a refusal to adapt to others also may generate a counterproductive spiral (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2001), such that employees' lack of social adaption might make them aware of their precarious work situation, lead them to perceive they are on their own and without a place in the organization, and stimulate desires to look for alternative employment.

From a positive perspective, the study's empirical findings indicate a subduing influence when employees can draw from valuable emotional regulation skills (Grant, Reference Grant2013; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Zhang and Tjosvold2013). In line with COR theory, employees who are capable of controlling their own emotions are less inclined to feel threatened by resource-draining workplace adversity, because they can deal more effectively with the associated stresses and uncertainties (De Clercq & Belausteguigoitia, Reference De Clercq and Belausteguigoitia2020; Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000). This beneficial effect is manifest in employees' reduced desire to vent their disappointments about dysfunctional political games as a refusal to adapt to the preferences of other members. Beyond the enhanced coping abilities that come with emotional regulation skills, employees who are equipped with them may also derive personal joy from being able to deal with the challenges of politicized decision-making processes, such that they experience their choice or ability not to take revenge for others' self-serving behaviors as a form of personal fulfillment (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000; Vigoda-Gadot & Meisler, Reference Vigoda-Gadot and Meisler2010). The likelihood that they take out their frustration by not adapting to others is further diminished then (Penney et al., Reference Penney, Spector, Fox, Sagie, Koslowsky and Stashevsky2003).

The mitigating role of emotional regulation skills in this negative relationship is especially relevant when considered together with the mediating effect of social adaptive behavior. As indicated by the moderated mediation analysis (Preacher et al., Reference Preacher, Rucker and Hayes2007), the strength of the indirect relationship between perceived organizational politics and turnover intentions, through social adaptive behavior, is contingent on employees' ability to contain their emotions. The frustration that arises with beliefs about dysfunctional politics translates less forcefully into an enhanced desire to quit, by refusing to adjust to colleagues, when employees can avoid getting angry (Hagemeister & Volmer, Reference Hagemeister and Volmer2018; Parke et al., Reference Parke, Seo and Sherf2015). Conversely, frustration with others' politically driven actions escalates into higher turnover intentions more powerfully, due to a reluctance to adapt, when employees cannot remain calm (Hobfoll & Shirom, Reference Hobfoll, Shirom and Golembiewski2000).

In summary, this study provides deeper insights into key factors that inform the link between perceived organizational politics and enhanced turnover intentions. We complement previous studies by explicating (1) how the propensity to ignore the preferences of organizational colleagues serves as an important factor that explains how this source of organizational adversity fuels plans to leave the organization and (2) how employees' emotional regulation skills are instrumental in suppressing this process. The results accordingly extend prior studies of the direct beneficial roles of emotion-based skills in stimulating various positive work outcomes (Grant, Reference Grant2013; Joseph & Newman, Reference Joseph and Newman2010; Meisler, Reference Meisler2014; Parke et al., Reference Parke, Seo and Sherf2015). That is, the merits of emotional regulation skills, as revealed herein, are indirect; employees who can control their temper and handle difficulties in rational instead of emotional ways are better placed to deal with colleagues who act in egoistic ways at the expense of others' interests. In this sense, this study provides critical insight into how employees can avoid doubled suffering—that is, from frustrations with dysfunctional political games, as well as from distractions due to their continuous ruminations about how the grass might be greener in other organizations—by leveraging their emotion-based skills.

Limitations and future research

This study contains some limitations, which suggest avenues for further research. First, it pinpoints social adaptive behavior as an unexplored mechanism that underlies the translation of organizational politics into enhanced turnover intentions, but other behavioral reactions could explain this connection too, such as concealing valuable knowledge from colleagues (Connelly & Zweig, Reference Connelly and Zweig2015), workplace ostracism (Jones, Carter-Sowell, Kelly, & Williams, Reference Jones, Carter-Sowell, Kelly and Williams2009), or overt efforts to undermine the organization's reputation (Skarlicki & Folger, Reference Skarlicki and Folger1997). Continued investigations could detail which intermediate behaviors might be most prevalent. In a related vein, we did not directly measure the mechanisms by which employees' beliefs about dysfunctional organizational politics translate into a lack of social adaptive behavior, such as perceived threats to their professional well-being or the associated depletion of self-esteem resources (Bentein et al., Reference Bentein, Guerrero, Jourdain and Chênevert2017). The mechanisms are consistent with the arguments of COR theory (Hobfoll et al., Reference Hobfoll, Halbesleben, Neveu and Westman2018), but it still would be useful to measure them formally. Yet another useful extension would be to consider explicitly the role of managerial power—in terms of condoning an organizational climate predicated on self-serving decision making (Landells & Albrecht, Reference Landells and Albrecht2013)—for determining the likelihood that employees respond to dysfunctional political games with diminished social adaptive behavior and subsequent turnover intentions.

Second, we focused on emotional regulation skills as a particular personal resource that may mitigate the escalation of perceived organizational politics into diminished social adaptive behavior and then a desire to leave the organization. Continued studies could investigate other personal factors that may serve as buffers, such as employees' passion for work (Baum & Locke, Reference Baum and Locke2004), psychological capital (Bouckenooghe, De Clercq, & Raja, Reference Bouckenooghe, De Clercq and Raja2019), emotional stability (Beehr, Ragsdale, & Kochert, Reference Beehr, Ragsdale and Kochert2015), or creative self-efficacy (Tierney & Farmer, Reference Tierney and Farmer2002). Pertinent organizational factors also may counter the hardships raised by the presence of dysfunctional politics, such as supportive leadership styles (Cai, Jia, & Li, Reference Cai, Jia and Li2017), trust in top management (Bouckenooghe, Reference Bouckenooghe2012), perceptions of organizational justice (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Harris and Harvey2007), or effective intra-organizational knowledge sharing (Huang, Hsieh, & He, Reference Huang, Hsieh and He2014).

Third, we tested the proposed theoretical framework in one industry (the food sector), which helped us avoid the concern that unobserved industry features influence the feasibility of finding alternative employment (Virga et al., Reference Virga, De Witte and Cifre2017). In addition, the conceptual arguments that underpinned the research hypotheses were industry-neutral, so we anticipate that the strength but not the nature of the theorized relationships may vary across industry sectors. As highlighted in the ‘Sample and data collection’ subsection, job possibilities are quite scarce in the food sector in Pakistan (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2020), so the statistical support we find for the proposed relationships, despite this challenge, underscores the validity of the conceptual framework. Nonetheless, multisector studies could clarify how pertinent industry factors might inform the conceptual framework. For example, in industry sectors characterized by an abundance of job opportunities, employees may be more eager to make plans to quit in response to frustrations about organizational politics and associated maladaptive behaviors relative to coworkers (Baranchenko et al., Reference Baranchenko, Xie, Lin, Lau and Ma2020). Alternatively, hypercompetitive environments (Chen, Lin, & Michel, Reference Chen, Lin and Michel2010) could encourage employees to accept some level of flexibility or rule deviation in their employer's decision-making processes, which could diminish their negative responses to politically based decisions.

Fourth, as noted, the conceptual arguments were country neutral, yet cultural factors still may have exerted effects in the tested theoretical framework. As indicated in the ‘Introduction,’ the contrasting roles of certain Pakistani cultural features—high-risk aversion may spur strong negative reactions to uncertainty-inducing organizational politics, but high collectivism may diminish such reactions (Hofstede et al., Reference Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov2010)—make Pakistan an interesting setting for testing the proposed theoretical framework. The empirical support for the research hypotheses indicates that the first reinforcing dynamic might be more prevalent than its suppressing counterpart. But we also reiterate that our theoretical arguments are general and not country-focused, so here again, we expect that the strength but not the nature of the theorized relationships may vary across countries. Another set of comparative studies might address how employees' beliefs about others' self-serving behaviors diminish their social adaptive behavior and then stimulate their turnover intentions, as well as the moderating role of pertinent personal and organizational resources in this process, in cultural settings other than Pakistan. Such comparisons would enable explicit considerations of how different cultural factors might subdue or trigger this study's focal relationships.

Practical implications

The results have important implications for managerial practice. The prevalence of egoistic behaviors within an organization's ranks—such that organizational members are primarily interested in what is best for them, not for the company overall—can generate significant frustration among other employees and elicit strong negative responses toward their colleagues and their employing organization in general. When employees feel threatened by the self-centered actions of their colleagues, they may suspend or discontinue their relationships with them, leaving them isolated and focused on energy-consuming ruminations about the possible benefits of quitting. Notable in this regard is that some employees might be reluctant to openly vent their frustrations about dysfunctional political decision making, because they do not perceive that others will listen, want to avoid being perceived as a tattletale or vulnerable, or worry that their complaints might backfire and hinder their future career development (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Rosen and Levy2009). Organizations accordingly should proactively work to detect self-centered actions among their employee bases and make it clear that these actions are unacceptable and counterproductive. Moreover, they should identify employees who might be most vulnerable to the political behaviors of other members—such as those who recently joined the organization or have rotated to a new department—and develop ways to encourage them to voice their complaints. For example, organizations could assign specific human resource managers as contact persons who gather complaints about politicized decision making or establish formally appointed ombudsmen with whom employees can share their concerns in complete confidence (Harrison, Hopeck, Desrayaud, & Imboden, Reference Harrison, Hopeck, Desrayaud and Imboden2013).

In addition to this general recommendation to avoid self-centered actions and decision making, the findings of this research might be especially valuable for organizations that are not able to eradicate dysfunctional politics from their ranks, because of ambiguous job descriptions, scarce organizational resources, or an organizational climate marked by distrust, for example (Poon, Reference Poon2003). Employees who are able to approach difficult situations in rational instead of emotional ways are better placed to develop effective coping strategies that mitigate the hardships that arise with others' self-centered actions, so these skills reflect important personal features that overly politicized organizations might leverage to diminish turnover within their ranks. In particular, organizations that can rely on the emotion-based competencies of their employee bases should be more effective in immunizing themselves against the risk that their employees alienate themselves from the rest of the organization, so the associated propensity to want to leave their employer is mitigated.

The selection and retention of employees who are equipped with such emotional regulation skills accordingly should be very useful for organizations with politicized work environments—as well as for the potential victims of these political actions, who can avoid a situation in which their own behavioral reactions leave them even more vulnerable to the self-centered actions of others (Kacmar & Baron, Reference Kacmar, Baron and Ferris1999; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Restubog and Zagenczyk2013). In addition to hiring and retaining emotionally skilled employees, organizations may also benefit from enhancing employees' emotional skill bases. For example, to help them control their emotions, training programs might be tailored to the development and nurturance of employees' emotional competencies (Mattingly & Kraiger, Reference Mattingly and Kraiger2019), as well as political skills to help employees navigate politicized decision-making climates (Banister & Meriac, Reference Banister and Meriac2015). In combination with such training, organizations could formally recognize employees' efforts to avoid certain behavioral responses that may spur enhanced turnover intentions, even when their work conditions are far from perfect. Any measure that enhances employees' capabilities to maintain control of their own emotions should be particularly useful in circumstances in which organizational politics are unavoidable.

Conclusion

This study adds to extant research on the detrimental effects that overly political organizational environments have on employees' work functioning, with a particular focus on the roles that their social adaptive behavior, or its lack thereof, and their emotional regulation skills play. The reluctance to adapt to others' actions and preferences constitutes an important reason that employees' beliefs about self-centered, behind-the-scenes decision-making drives them toward ruminations about alternative employment. The potency of this explanatory behavioral mechanism depends though on how capable employees are in containing their own emotions. These insights could provide a platform for continued investigations of how organizations can prevent the escalation of dysfunctional actions into heightened intentions to leave.