Violence risk assessment has become increasingly important for clinicians treating adults with mental disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression (Reference Douglas, Cox and WebsterDouglas et al, 1999; Reference Monahan and SteadmanMonahan & Steadman, 1994). To optimise violence prediction, research has uncovered variables empirically related to community violence (Reference Douglas and WebsterDouglas & Webster, 1999; Reference Monahan, Steadman and RobbinsMonahan et al, 2000; Reference Steadman, Silver and MonahanSteadman et al, 2000; Harris et al, Reference Harris, Rice and Cormier2002, Reference Harris, Rice and Camilleri2004; Nichols et al, 2004). Although ‘static’, unchanging characteristics such as gender, history of violence, past child abuse and psychopathy are important to consider when predicting violence risks, these factors are not amenable to change and therefore are seen as less applicable for reducing violence risk (Reference Steadman, Monahan, Robbins and HodginsSteadman et al, 1993; Reference Douglas, Cox and WebsterDouglas et al, 1999; Reference Skeem and MulveySkeem & Mulvey, 2001). Instead, ‘dynamic’ factors could point to methods of preventing community violence, since such variables are malleable (Reference Steadman, Monahan, Robbins and HodginsSteadman et al, 1993; Reference HeilbrunHeilbrun, 1997; Reference Strand, Belfrage and FranssonStrand et al, 1999; Reference Monahan, Steadman and RobbinsMonahan et al, 2000; Reference Douglas and SkeemDouglas & Skeem, 2005). Although static factors are statistically reliable, the dynamic factors are those that are changing and therefore pertinent to violence risk management. One dynamic factor potentially linked to violence in mental disorders is a patient's level of treatment engagement. Research confirms that treatment adherence reduces violence risk (Swartz et al, Reference Swartz, Swanson and Hiday1998a ,Reference Swartz, Swanson and Hiday b ; Swanson et al, Reference Swanson, Swartz and Elbogen2004a ,Reference Swanson, Swartz and Elbogen b ). Another facet of treatment engagement, however, has received less attention: namely, patients’ perceptions of treatment benefit. Because clinicians consider exactly this type of information when assessing violence risk (Elbogen et al, Reference Elbogen, Mercado and Scalora2002, Reference Elbogen, Huss and Tomkins2005), further empirical investigation elucidating the relationship between perceived treatment benefit and violent behaviour would seem especially relevant to psychiatric service providers. The aim of our study therefore was to explore the link between perceived treatment benefit and violent behaviour among patients with mental disorders.

METHOD

The study method is described in detail elsewhere (Reference Monahan, Redlich and SwansonMonahan et al, 2005). In brief, approximately 200 out-patients from publicly funded mental health treatment programmes were sampled from each of five sites; Chicago, Illinois; Durham, North Carolina; San Francisco, California; Tampa, Florida; and Worcester, Massachusetts (total n=1011). Sample inclusion criteria were age 18–65 years, speaker of English or Spanish, had first mental health treatment episode at least 6 months ago, and had at least one out-patient treatment encounter with a publicly supported mental health service provider within the past 6 months. Persons treated only for substance misuse and not for any other psychiatric disorder were excluded. Otherwise, the inclusion criteria did not specify particular mental health diagnoses or level of acuity.

At the Worcester, Tampa and San Francisco sites, potential participants were recruited sequentially in the waiting rooms of out-patient clinics of the community mental health centres. In Durham a list of potentially eligible individuals was created from management information system data, and patients were randomly selected to be approached for participation in the study. The Chicago site used both sampling methods, enrolling about half the sample using the waiting-room approach and the other half using the eligibility-list approach. Participants were enrolled after receiving a complete description of the study and providing written informed consent. All sites received approval from their respective institutional review boards. Refusal rates varied from 2% to 13% across sites. A single structured interview, lasting about 90 min, was administered in person by a trained lay interviewer. Participants were paid US$25 for the interview.

Sample characteristics

Consistent with the core paper from this study (Reference Monahan, Redlich and SwansonMonahan et al, 2005), we report the cross-site range of means and proportions for these characteristics, i.e. the highest and lowest values across the five sites. The mean age of participants ranged from 41.3 to 46.7 years. Between 24.6% and 41.1% of respondents reported having less than a high school education and between 12.5% and 24.5% of respondents were married or cohabiting. The proportion from Black and minority ethnic groups ranged from 28.5% to 64.0%, and the proportion of male participants ranged from 32.4% to 64.5%.

Regarding clinical characteristics, between 41.5% and 49.5% of respondents had a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder, between 14.4% and 17.6% had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and between 27.5% and 30.7% had major depression. Rates of substance abuse comorbidity ranged from 13.9% to 35.5% between sites, while mean scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and the Global Assessment of Functioning (see below) ranged from 31 to 33 and 18 to 19 respectively across the sites. Between 30.2% and 38.2% of respondents indicated that they had not adhered to treatment during the past 6 months. Personality disorder diagnoses ranged from 13% to 26% across sites. Between 47.6% and 63.3% of respondents reported four or more lifetime hospitalisations. Finally, between 25.5% and 47.6% of respondents reported recognising the need for mental health treatment, and between 43.4% and 54.4% of respondents reported positive benefits from recent mental health treatment.

Measures

Violence and other aggressive acts

We used the MacArthur Community Violence Interview (Reference Monahan, Steadman and RobbinsMonahan et al, 2000; Reference Steadman, Silver and MonahanSteadman et al, 2000; Reference MonahanMonahan, 2002) to measure violent and aggressive behaviour at three levels of severity:

-

(a) ‘serious violence’, corresponding to any assault using a lethal weapon or resulting in injury, and threat with a lethal weapon in hand or any sexual assault;

-

(b) ‘other aggressive acts’, corresponding to simple assault without injury or weapon use;

-

(c) ‘any physically assaultive behaviour’, denoting a violence composite capturing serious violence and other aggressive acts.

This operationalisation of community violence corresponds to the concept of violence employed in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study and to other studies of violence among people with mental illness (Reference Swanson, Swartz and Van DornSwanson et al, 2006).

Perceived treatment effectiveness

Commentators have noted two important and distinct dimensions of perceived treatment benefit (Reference PerkinsPerkins, 2002). The first is perceived treatment effectiveness, which was measured using the Consumer Satisfaction Questionnaire (Reference GanjuGanju, 1999) assessed with four items that were summed and dichotomised above the median; those responding in the negative to two or more of these four questions served as the reference group and were coded as 0. Items from this questionnaire included, ‘As a direct result of the services I received, (a) I deal more effectively with daily problems, (b) I am better able to control my life, (c) I am getting along better with my family, and (d) my symptoms are not bothering me as much’ (Reference GanjuGanju, 1999). Teague et al (Reference Teague, Ganju and Hornik1997) describe the reliable use of this scale to measure patients’ views of treatment effectiveness.

Perceived treatment need

A second facet of perceived treatment benefit is a patient's perceptions of treatment need, which in this study was measured using questions from the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study section on perceived barriers to care (Reference Blazer, George and LandermauBlazer et al, 1985). Participants were asked about reasons for not attending mental health treatment care via three items that were summed and dichotomised above the median; those responding in the affirmative to any of these three questions served as the reference group and were coded as 0. The questions were, ‘You think that going for help probably wouldn't do any good’; ‘You think the [mental health] problem might get better by itself’ and ‘You want to solve the [mental health] problem on your own’. Research on violence and arrests in mental disorders confirm good psychometric properties on employing the ECA study section on perceived barriers to care in order to measure patients’ beliefs about the need for psychiatric treatment (Reference Elbogen, Mustillo and Van DornElbogen et al, 2006).

Demographic characteristics

Demographic variables included: age (reference group 44 years or younger), education (reference group high school or beyond), married or cohabiting (reference group single), ethnic status (reference group White) and gender (reference group female).

Clinical factors

Psychiatric diagnosis was based on chart diagnoses at the mental health centres. This analysis compares psychotic disorder with affective disorders as well as the presence or absence of an Axis II personality disorder. The anchored version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Reference Woerner, Mannuzza and KaneWoerner et al, 1988) was used to assess current psychiatric symptoms and the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF; Reference Endicott, Spitzer and FleissEndicott et al, 1976; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) was used to score overall functioning, with low scores indicating more severe functional impairment. Treatment adherence was measured by the question, ‘In the past 6 months, were there times when you thought you should go to a doctor or clinic for mental health or alcohol or drug problems, but did not go?’ (0 nonadherent, 1 adherent). Age at onset of the disorder and the number of lifetime hospitalisations were included in the model as well. All of these factors were dichotomised above the median to capture non-linear associations.

Substance misuse

Substance misuse was assessed with questions adapted from the CAGE questionnaire (Reference Allen, Eckard and WallenAllen et al, 1988). This consists of four questions asking whether people felt they needed to cut down on their drinking, were annoyed by people complaining about their drinking, felt guilty about drinking, and if they need an eye-opener in the morning. These same four questions were also asked in relation to drug use. For these analyses we combined alcohol and drug misuse into a single dichotomous variable, coded 1 for one or more substance misuse symptoms and 0 for no symptoms.

Statistical analysis

We used logistic regression to examine the associations between participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics and the likelihood of engaging in any physically assaultive behaviour, in addition to other aggressive acts and violence in the past 6 months. For the purpose of multivariable modelling, pooling the data across sites offered the advantage of greater statistical power, but also posed two problems that required adjustment in the analyses. First, we had to account for site effects and site-by-covariate interactions associated with violence. To examine and control for these site effects, we used Zelen's test of the homogeneity of odds ratios (Reference ZelenZelen, 1971; StatXact, 2003: pp. 511–517). The Zelen statistic allowed us to test the null hypothesis that the relative risk for the multiple measures of violence did not vary across the five sites, but represented a sampling distribution from a common population. If Zelen's test showed the sites’ odds ratios for a given variable were homogeneous, we then pooled the data for that variable and calculated a common odds ratio across sites. The second problem was that pooling the data could have distorted statistical inferences, insofar as the observations within each site were not independent. Without an adjustment for the clustered nature of the data, the standard errors around the pooled estimates would have been understated, leading to overly liberal tests of statistical significance. Accordingly, we used the same specialised statistical software (StatXact, 2003) to adjust significance tests and confidence intervals around the common (pooled) odds ratios.

For multivariable analysis we used a companion statistical package designed to conduct multivariable logistic regression with stratified data (LogXact, 2002: pp. 83–103). These techniques provided the appropriate correction of variance estimates, taking into account within-site correlation of observations. Specifically, the software uses the Cochran–Armitage method, as adapted by Rao & Scott (Reference Rao and Scott1992), to adjust the ‘effective sample size’ for design effects that occur with a clustered sample (LogXact, 2002: pp. 755, 774).

Finally, we dichotomised independent variables at the median to meet statistical assumptions of normal distribution and to allow a more informative classification of respondents in terms of the presence or absence of relevant characteristics of perceived treatment benefit that might be associated with violence. Along these lines, we appeal to the argument developed by Farrington & Loeber: ‘Dichotomized variables do not contain inherently less information than scales; it all depends on the relative number of variables of each type and on the accuracy of measurement’ (Reference Farrington and LoeberFarrington & Loeber, 2000: p. 107). These authors advocate dichotomising non-linear explanatory variables because this allows a risk- and protective-factor approach to the analysis, interpretation and presentation of data on crime and violence, which is consistent with the goals of our study.

RESULTS

Table 1 displays the prevalence of the various levels of violence by sample characteristics. Across the sites (pooled n=1011) the proportion of respondents engaging in other aggressive acts during the past 6 months ranged from 12.6% to 18.2% with an overall proportion of 14.1%, whereas the proportion of respondents engaging in serious violence ranged from 3.4% to 8.5% with an overall proportion of 5.5%. Finally, a composite of ‘any violence’ (i.e. other aggressive acts or serious violence) ranged from 18.3% to 21.0% with an overall proportion of 19.7%.

Table 1 Prevalence of violent and aggressive behaviour over preceding 6 months by sample characteristics

| n | Serious violence n (%) | Other aggressive acts n (%) | Violence composite n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1011 | 56 (5.54) | 143(14.14) | 199(19.68) |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age | ||||

| Below median (<44 years) | 485 | 38 (7.84) | 82(16.91) | 120(24.74) |

| Median or above (44 years or older) | 525 | 18 (3.43) | 60(11.43) | 78(14.86) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 313 | 20 (6.39) | 41(13.10) | 61(19.49) |

| High school or beyond | 697 | 36 (5.16) | 102(14.63) | 138(19.80) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 828 | 43 (5.19) | 107(12.92) | 150(18.12) |

| Married, cohabiting | 182 | 13 (7.14) | 36(19.78) | 49(26.92) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Black and minority | 446 | 26 (5.83) | 70(15.70) | 96(21.52) |

| White | 565 | 30 (5.31) | 73(12.92) | 103(18.23) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 509 | 33 (6.48) | 57(11.20) | 90(17.68) |

| Female | 502 | 23 (4.58) | 86(17.13) | 109(21.71) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Treatment adherence | ||||

| Yes | 655 | 23 (3.51) | 61 (9.31) | 84(12.82) |

| No | 355 | 33 (9.30) | 81(22.82) | 114(32.11) |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Psychotic | 455 | 16 (3.52) | 43 (9.45) | 59(12.97) |

| Non-psychotic | 556 | 40 (7.19) | 100(17.99) | 140(25.18) |

| Substance use | ||||

| Abstinent | 797 | 28 (3.51) | 103(12.92) | 131(16.44) |

| Abuse/dependece | 214 | 28(13.08) | 40(18.69) | 68(31.78) |

| BPRS score | ||||

| Below median (<31) | 471 | 17 (3.61) | 51(10.83) | 68(14.44) |

| Median or above (≥31) | 539 | 39 (7.24) | 92(17.07) | 131(24.30) |

| GAF score | ||||

| Below median (<48) | 486 | 30 (6.17) | 80(16.46) | 110(22.63) |

| Median or above (≥48) | 524 | 26 (4.96) | 63(12.02) | 89(16.98) |

| Onset of mental illness | ||||

| <16 years of age | 346 | 27 (7.80) | 61(17.63) | 88(25.43) |

| ≥16 years of age | 664 | 29 (4.36) | 73(11.58) | 102(15.36) |

| Personality disorder | ||||

| No | 807 | 43 (5.32) | 99(12.25) | 139(17.22) |

| Yes | 203 | 13 (6.40) | 39(19.21) | 51(25.12) |

| Number of lifetime hospitalisations | ||||

| Below median (<4) | 460 | 20 (4.35) | 63(13.70) | 83(18.04) |

| Median or above (≥4) | 545 | 36 (6.61) | 78(14.31) | 114(20.92) |

| Perceived treatment benefit | ||||

| Perceived treatment effectiveness | ||||

| No (below median) | 521 | 39 (7.49) | 92(17.66) | 131(25.14) |

| Yes (above median) | 490 | 17 (3.47) | 51(10.41) | 68(13.88) |

| Perceived treatment need | ||||

| No (below median) | 467 | 38 (8.12) | 83(18.59) | 121(25.91) |

| Yes (above median) | 543 | 18 (3.31) | 51 (9.39) | 69(12.71) |

We first examined bivariate associations between the three levels of violence and a range of salient demographic and clinical variables. Next, multivariable associations were tested using logistic regression procedures. The multivariable models were conducted in three stages: first, the domain of demographic characteristics was assessed; then the clinical characteristics were combined with the demographic characteristics; finally, the factors assessing perceived need for and benefits from recent treatment were added to the model along with the other two domains. All models also controlled for site and the clustering of observations within site.

Table 2 displays the results for the composite measure of any physically assaultive behaviour. In the demographic domain there was a significant and negative bivariate relationship between age and any physically assaultive behaviour (OR=0.52, P<0.001), whereas marital status (OR = 1.69, P<0.01) was positively related to any physically assaultive behaviour. In the clinical domain, significant and negative bivariate associations were present for treatment adherence (OR=0.31, P<0.001), psychotic diagnosis (OR=0.44, P<0.001) and GAF score (OR=0.67, P<0.05), whereas substance misuse (OR = 2.42, P<0.001), personality disorder (OR=1.59, P<0.01) and BPRS score (OR=1.90, P<0.001) were positively associated with any physically assaultive behaviour. Finally, both perceptions of the effectiveness of treatment (OR=0.48, P<0.001) and the need for treatment (OR=0.33, P<0.001) were negatively associated with any physically assaultive behaviour.

Table 2 Cross-site multivariable models for violence composite (any physically assaultive act)

| Independent variables | Bivariates | Stage 12 | Stage 23 | Stage 34 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR1 | (95% CI) | OR1 | (95% CI) | OR1 | (95% CI) | OR1 | (95% CI) | |

| Demographic variables | ||||||||

| Age >44 years | 0.52 | (0.38-0.73)*** | 0.54 | (0.39-0.74)*** | 0.57 | (0.40-0.81)** | 0.58 | (0.41-0.84)** |

| Less than high school education | 0.99 | (0.69-1.40) NS | 0.97 | (0.69-1.39) NS | 1.00 | (0.69-1.46) NS | 0.97 | (0.66-1.42) NS |

| Married | 1.69 | (1.14-2.50)** | 1.56 | (1.06-2.31)* | 1.29 | (0.85-1.97) NS | 1.31 | (0.86-2.02) NS |

| Black and minority ethnic group | 1.24 | (0.89-1.74) NS | 1.26 | (0.90-1.76) NS | 1.38 | (0.96-1.98) NS | 1.42 | (0.99-2.05) NS |

| Male | 0.76 | (0.54-1.05) NS | 0.74 | (0.53-1.04) NS | 0.70 | (0.49-1.02) NS | 0.71 | (0.49-1.02) NS |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||||

| Treatment adherence | 0.31 | (0.22-0.43)*** | 0.43 | (0.30-0.62)*** | 0.51 | (0.35-0.73)*** | ||

| Psychotic disorder | 0.44 | (0.31-0.63)*** | 0.47 | (0.32-0.70)*** | 0.47 | (0.32-0.70)*** | ||

| Substance misuse | 2.42 | (1.67-3.48)*** | 2.04 | (1.37-3.02)*** | 1.97 | (1.31-2.93)*** | ||

| BPRS score ≥31 | 1.90 | (1.36-2.67)*** | 1.22 | (0.85-1.77) NS | 1.09 | (0.75-1.60) NS | ||

| GAF score ≥48 | 0.67 | (0.47-0.95)* | 0.68 | (0.45-1.00) NS | 0.71 | (0.48-1.07) NS | ||

| Onset of disorder < 16 years | 1.85 | (0.53-1.04)*** | 1.32 | (0.92-1.90) NS | 1.31 | (0.91-1.90) NS | ||

| Personality disorder | 1.59 | (1.10-2.29)** | 1.34 | (0.89-2.02) NS | 1.25 | (0.83-1.91) NS | ||

| Hospitalised ≥4 times | 1.20 | (0.86-1.67) NS | 1.40 | (0.97-2.01) NS | 1.38 | (0.96-1.98) NS | ||

| Perceived treatment benefit | ||||||||

| Perceived treatment effectiveness | 0.48 | (0.34-0.67)*** | 0.69 | (0.48-1.00)* | ||||

| Perceived treatment need | 0.33 | (0.22-0.50)*** | 0.59 | (0.41-0.85)** | ||||

In the final multivariable model (stage 3), age was negatively associated with any physically assaultive behaviour (OR=0.58, P<0.01). Clinically, treatment adherence (OR=0.51, P<0.01) and having a psychotic diagnosis (OR=0.47, P<0.001) were negatively associated with the outcome, whereas substance misuse (OR = 1.97, P<0.001) was positively associated with the same. With respect to perceived treatment benefit, violence was negatively associated with both perceived treatment effectiveness (OR=0.69, P<0.05) and perceived treatment need (OR=0.59, P<0.01).

To assess the constancy of these findings across different levels of violence severity, we also modelled both serious violence and other aggressive acts. Bivariate associations were virtually identical to those described above for any physically assaultive behaviour. In the multivariable model assessing serious violence, age (OR=0.39, P<0.05), having a psychotic diagnosis (OR=0.44, P<0.05) and perceiving the need for treatment (OR=0.44, P<0.05) were negatively associated with violence. In the multivariable model assessing other aggressive acts, age (OR=0.62, P<0.05), treatment adherence (OR=0.53, P<0.01), having a psychotic diagnosis (OR=0.43, P<0.001) and substance misuse (OR=1.91, P<0.01) were significantly associated. Additionally, there was a significant and negative association between other aggressive acts and perceived treatment need (OR=0.45, P<0.01).

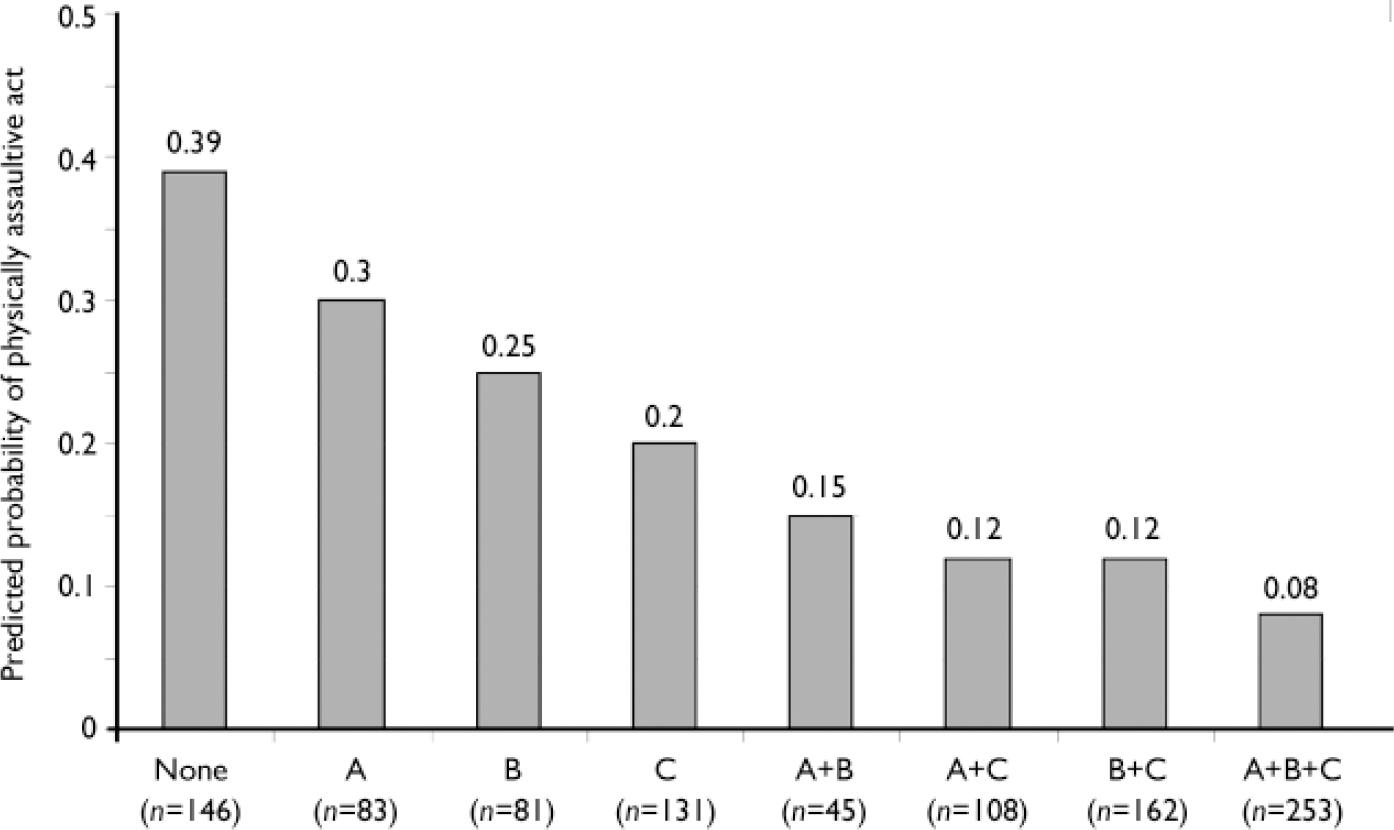

Figure 1 illustrates the odds of any physically assaultive behaviour as a function of level of treatment engagement, as measured by perceived treatment need, perceived treatment benefit and treatment adherence. With respect to violence risk, these findings show that in the absence of these three factors the predicted probability of any physically assaultive behaviour was 0.39. However, the presence or endorsement of these factors was associated with a greatly decreased probability of any physically assaultive behaviour (0.08). It should be noted that probabilities were calculated controlling for all other variables in the model; thus, even individuals in the A+B+C group may in fact possess characteristics increasing odds of violence (e.g. substance misuse or young age).

Fig. 1 Predicted probability of violence composite as a function of level of treatment engagement. A, perceived treatment effectiveness (above median); B, perceived treatment need (above median); C, treatment adherence reported in past 6 months.

Interestingly, most participants’ data were clustered in the ‘none’ and ‘all’ groups, suggesting connection between adherence behaviour and perceived treatment benefit. Correspondingly, there were fewest participants when treatment adherence was present and perceived treatment need or effectiveness was absent (and vice versa). Spearman correlations confirmed treatment adherence was significantly associated with perceived treatment need (r=0.27, P<0.0001) and with perceived treatment effectiveness (r=0.18, P<0.0001).

We additionally examined whether treatment engagement was related to psychiatric diagnosis. We found that people with affective disorders were more likely to report treatment non-adherence than people with psychotic disorders (41% v. 28%; χ2=19.02, d.f.=1, P<0.0001).

However, However, there was no relationship between treatment adherence and personality disorder. Interestingly, although perceived treatment need was not related to either Axis I or Axis II disorders, perceived treatment effectiveness was significantly related to both: specifically, people with a psychotic disorder (52%) were somewhat more likely to perceive their treatment as effective than people with an affective disorder (45%; χ2=4.9, d.f.=1, P=0.02), and people with a personality disorder (39%) were less likely to perceive treatment as effective than people without a personality disorder (51%; χ2=7.46, d.f.=1, P= 0.0063). Thus, although ‘perceived treatment need’ and ‘perceived treatment effectiveness’ are conceptually related, they appear to tap into two distinct facets of treatment engagement.

DISCUSSION

The data revealed significant bivariate associations between different levels of violent behaviour and both the dimensions of perceived treatment benefit measured: perceived treatment effectiveness and perceived treatment need. Other findings were consistent with past research on the relationship between violence and age (Reference Monahan and SteadmanMonahan & Steadman, 1994), cohabitation (Reference Estroff, Swanson and LachicotteEstroff et al, 1998), personality disorder (Reference Moran, Walsh and TyrerMoran et al, 2003; Reference Walsh, Moran and ScottWalsh et al, 2003), substance misuse (Reference Steadman, Mulvey and MonahanSteadman et al, 1998), psychiatric symptoms (Swanson et al, Reference Swanson, Holzer and Ganju1990, Reference Swanson, Swartz and Van Dorn2006) and poor functioning (Reference Swanson, Swartz and EstroffSwanson et al, 1998). Multivariate analyses controlling for these and other covariates demonstrated that perceived treatment need was related to significantly reduced odds of all three levels of violence severity analysed.

Clinical implications

Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, there are several ways to interpret the connection between perceived treatment need and violent behaviour among people with mental disorder. First, one could conjecture that people who do not perceive they need treatment are less likely to attend treatment and take their medications. These individuals may instead ‘self-medicate’ by misusing alcohol or illicit drugs to stave off psychiatric symptoms. Such lack of engagement in services may therefore lead to relapse and increase the chances of violent behaviour. This interpretation is consistent with sociocognitive theories of behaviour change, such as the health belief model (Reference Norman, Abraham and ConnerNorman et al, 2000), self-determination theory (Reference Ryan and DeciRyan & Deci, 2000) and the transtheoretical model (Reference Prochaska and DiClementeProchaska & DiClemente, 1983), which posit that perceptions about treatment benefit predict treatment adherence. To the extent this causal pathway exists, interventions that address perceived treatment need, such as motivation interviewing (e.g. Reference Ruesch and CorriganRuesch & Corrigan, 2002), may be warranted as means of managing – and potentially reducing – violence risk among people with mental disorders.

Another possibility is that violent behaviour might lead to a patient feeling less confident about the benefits of the treatment he or she may have been receiving. Specifically, if a person has been violent and then arrested or involuntarily detained in hospital, the often circuitous process of accessing services (even if the patient tries to do so) after incarceration or hospitalisation may colour people's assessment of the value of these services or their effectiveness, compared with people who have not recently been violent.

This would be accentuated by more difficult access associated with public health insurance-related barriers and low income, certainly characteristic of a sample of patients in the public mental health system in the USA. Thus, violent behaviour may affect a patient's attitudes about the benefits and needs for treatment, rather than the other way around.

However, there is a final interpretation of the data: the statistically significant association between perceived treatment need and violence may indicate that both of the aforementioned causal pathways are present, and are perhaps reinforcing one another. To illustrate, one could imagine a patient with a mental disorder who is violent and arrested and then has difficulty reconnecting to services in the community. Thus, this patient might very well become sceptical about the benefits of treatment, which in turn could lead to poor adherence to prescribed medications, substance misuse to self-medicate and increased psychiatric symptoms – each of which elevate the risks of violence. The findings in this study may thus indicate a cycle in which patients’ perceptions of treatment benefit and violence influence one another reciprocally.

Limitations

Although this study is a first step into exploring the link between perceived treatment benefit and community violence among people with mental disorders, it does have limitations that need to be considered. The overall effect of mental disorder per se cannot be examined using these data, since treatment for mental disorder was a requirement for study participation, and no comparison group without treated mental illness was included. Despite use of sample weighting and robust variance estimation techniques to improve generalisability, it is difficult to define with precision the population with treated major mental disorders to which our results should generalise. In particular, the study surveyed patients connected with mental health services in the USA, who may be different from patients with psychiatric disorders in other countries.

Additionally, it should be noted that the study examines patients’ perceptions of treatment need, as opposed to whether patients’ need for treatment was actually met. If a patient has a need for treatment and the treatment is not provided, or is provided but is inappropriate, then one might anticipate that ‘unmet need’ would be positively associated with violence. Correspondingly, whereas 99% of patients in the sample were actively receiving pharmacological treatment, we did not measure the amount of psychosocial treatment obtained. Thus, future research needs to examine the interconnections between the quality and type of treatment provided, patients’ perceptions of treatment benefit, and violent behaviour.

Finally, our study relied only on self-report to obtain sensitive personal information about committing violent acts. Recent studies using composite indices of violence with multiple informants and record reviews have found higher rates of violence in psychiatric populations than those in our study (Reference Steadman, Mulvey and MonahanSteadman et al, 1998; Reference Swanson, Borum and SwartzSwanson et al, 1999). Further, it is possible that because our sample involved many patients over 40 years old (i.e. past the peak age of violent behaviour), violence rates might have been further influenced. This implies that our findings are probably conservative estimates of the true prevalence of violent behaviour in people with mental disorders.

Future research

The findings provide empirical support for the assertion that perceived treatment need is associated with reduced levels of violence among patients with mental disorders. Future research is needed to replicate findings, using longitudinal data measuring violence from multiple sources. Systematic examination of dynamic, malleable variables such as perceived treatment benefit is needed in scientific literature (as well as in clinical practice) because information on these variables can point to potential risk management strategies. At the very least, the results from this survey of over a thousand patients with mental disorders appear to support the clinical intuition that treatment engagement is important to consider in the context of violence risk assessment. Indeed, the findings also suggest that clinical consideration of patients’ perceived need for treatment can help enhance violence risk assessment in psychiatric practice settings.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.