Introduction

Archaeological research on Islamic sites in Ethiopia, and more generally in the Horn of Africa, has been limited. This is a significant omission, as Ethiopia was in contact with the earliest Islamic communities in western Arabia from the early seventh century AD, and Muslims were soon established in the Horn of Africa (see Insoll Reference Insoll2003, Reference Insoll2021a). Excavations at Harlaa in eastern Ethiopia, completed as part of the Becoming Muslim project (ERC-2015-AdG BM694254), have begun to redress this lack of research, establishing occupation and material sequences, reconstructing the chronology of Islamisation and assessing its material markers. In so doing, these new data challenge assumptions of cultural heterogeneity and teleological accounts of the Islamic conversion process. Rather, the results indicate cosmopolitanism, perhaps best defined as a willingness to engage with “the other” (Hannerz Reference Hannerz1990: 239). As such, the Harlaa excavations contribute to the emerging image of wider medieval Ethiopia as being similarly cosmopolitan and less constrained by the religious, ethnic and territorial particularism than perhaps once thought (see Insoll Reference Insoll2021a).

Harlaa

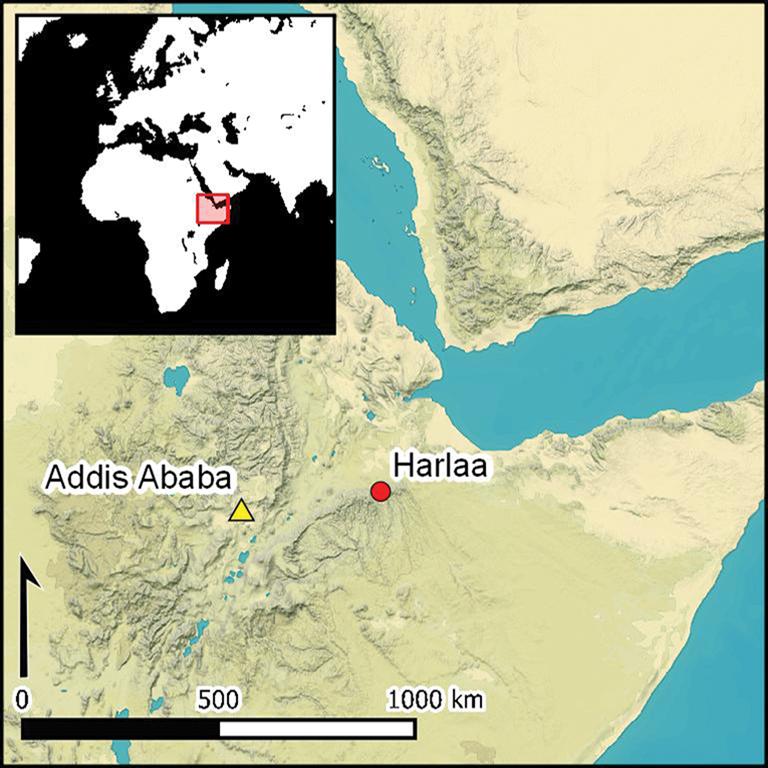

The investigations at Harlaa (9°29′10.22″ north, 41°54′36.96″ east) have provided the first significant evidence for medieval Islamic settlement, commerce and manufacturing in Ethiopia. The site is located at 1700m asl, on the edge of the main fault escarpment of the southern Afar margin, approximately 40km north-west of Harar and 15km south-east of Dire Dawa (Khalaf & Insoll Reference Khalaf and Insoll2019) (Figure 1). The accepted archaeological name, Harlaa, relates to the common appellation ‘Harla’ given to ruined stone-built towns and funerary monuments in the region. These sites are ascribed by the current inhabitants—the Oromo—to legendary ancient giants (Chekroun et al. Reference Chekroun, Fauvelle-Aymar, Hirsch, Ayenachew, Zeleke, Onezime, Shewangizaw, Fauvelle-Aymar and Hirsch2011: 79) who previously occupied the region (Joussaume & Joussaume Reference Joussaume and Joussaume1972: 22) in the mid sixteenth century (all dates herein are AD, unless otherwise specified). Only limited survey, and no excavation, had been undertaken at Harlaa prior to 2015 (Chekroun et al. Reference Chekroun, Fauvelle-Aymar, Hirsch, Ayenachew, Zeleke, Onezime, Shewangizaw, Fauvelle-Aymar and Hirsch2011; Insoll et al. Reference Insoll, Maclean and Engda2016). Survey conducted as part of the current project indicates that the settlement was built in a series of terraced blocks running north over two main and several smaller hills and slopes (Figure 2). Harlaa comprises several elements, including a central settlement area, workshops, at least three early mosques, wells, lengths of fortification wall and cemeteries to the north, east and west (Insoll et al. Reference Insoll, Maclean and Engda2016, Reference Insoll, Khalaf, Maclean and Zerihun2017) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. The location of Harlaa within Ethiopia (map prepared by N. Khalaf).

Figure 2. Harlaa survey plan and excavation locations (figure prepared by N. Khalaf).

Excavations and architecture in Harlaa

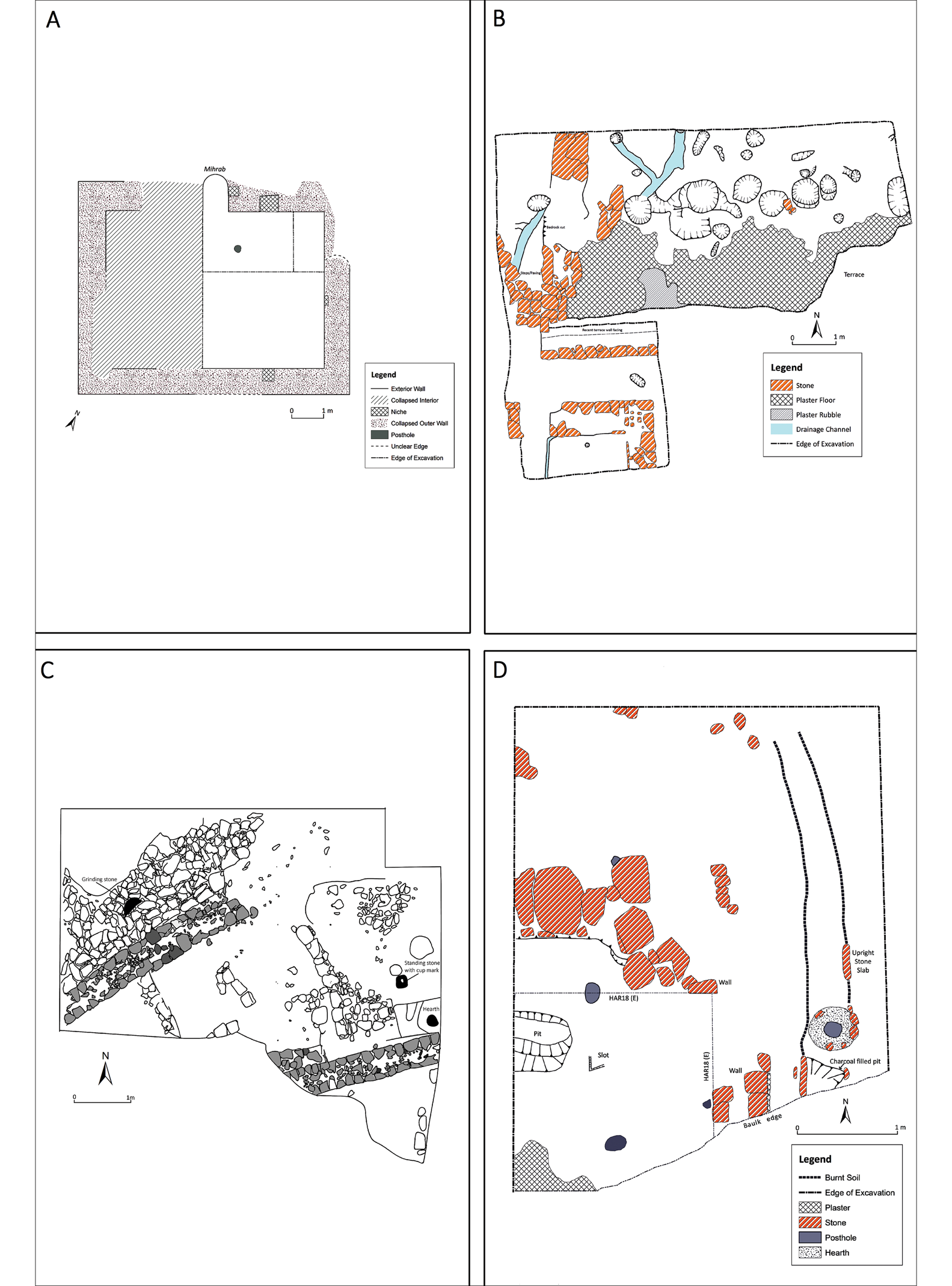

Since 2015, excavations over five fieldwork seasons have revealed a mosque (area A), a workshop complex (area B, except labelled A in 2016), cemeteries (areas C and D), a house with an associated industrial/kitchen facility (area E) and part of an extensive building complex—probably with a civic function (area F) (Figure 2). Twenty-seven AMS dates have so far been obtained from six areas of the site (Table 1), indicating occupation between the mid sixth and fifteenth centuries AD. There was a notable highpoint in trade and manufacturing, attested by both ceramic and radiocarbon dates, between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Table 1. Cumulative AMS radiocarbon dates from the Harlaa excavations. Dates calibrated in BetaCal 3.21 by Beta Analytic, using the IntCat13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2013).

¹ Dates from charcoal; 2 dates from bone collagen.

The style of architecture varies little across the site. Walls are constructed from locally sourced limestone block faces with a rubble fill. Blocks, varying in size from approximately 0.10 × 0.10m to 0.30 × 0.30m, were cut to shape and their external face(s) finished (Figure 3A). The mosque (A) provides an exception (Figure 4A) in that its walls were built of limestone blocks, and the mihrab from cut travertine blocks (Figure 3B). While this choice of stone may have been to facilitate the requisite curvature, it also suggests Red Sea and Swahili coastal influences as it resembles, for example, the eleventh- to twelfth century mosque at Kilwa Kiswani in southern Tanzania (Pradines & Blanchard Reference Pradines and Blanchard2016: 14), or the undated “mosque with two mihrabs” at Zeyla, Somaliland (Fauvelle-Aymar et al. Reference Fauvelle-Aymar, Hirsch, Champagne, Fauvelle-Aymar and Hirsch2011: 46). This is significant for the exploration of both cosmopolitanism and Islamisation, as it suggests intra-African relationships that may have contributed both to Islamic practice and population diversity at Harlaa.

Figure 3. Architectural elements at Harlaa: A) cut limestone blocks used on a corner and inner wall face; the external face is a recent Oromo field-terrace wall (HAR-F); B) mihrab made from cut travertine blocks (HAR-A); C) defensive wall made from large stone blocks; D) decorative plaster fragment (HAR-E); E) section of stone slab floor (HAR-B); F) travertine slabs used to construct tombs (HAR-C) (photographs by T. Insoll).

Figure 4. Plans of the excavated buildings: A) the mosque (HAR-A); B) the civic building (HAR-F); C) the workshop complex (HAR-B); D) the domestic building (HAR-E).

Other architectural techniques are also recorded at Harlaa. A mixture of larger (up to 1m in length), partially worked and unworked stones were used in the defensive wall (Figure 3C). Mortar was generally not used in wall construction, but plaster was sometimes applied, as it was on the interior of the civic building (HAR-F). Two fragments of decorated wall plaster incised with a geometric or vegetal pattern were recovered from the domestic building (HAR-E) (Figure 3D). Some floors were also plastered (Figure 4B); others comprised stone slabs (Figure 3E), including schist blocks in the workshop complex (HAR-B). Earthen floors laid over packing layers of faunal remains, hearth pits and hearth stones, anvils (including one with a carved cupule), and postholes were found inside the four small, cell-like rooms recorded in the south of the workshop complex (Figure 4C). The presence of postholes suggests the use of wooden pillars to support roofs (HAR-A, HAR-B, HAR-E), and stone-lined pits possibly for column bases (HAR-F). In addition to simple burials, some tombs were demarcated by large, flat travertine slabs laid on edge to form cell-like structures (HAR-C) (Figure 3F). Numerous pits across the site were employed for storage and waste disposal (Figure 4B & 4D).

Trade and other contacts

Harlaa was an entrepot receiving and supplying goods and materials via both maritime and land-based trade networks over a large geographic area. Archaeological material attests contacts—direct and indirect—with the Red Sea, the western Indian Ocean, China, South and Central Asia, Egypt, the Ethiopian interior, the East African coast and the Persian/Arabian Gulf. These networks presumably served to create and maintain local and transnational social relationships, contributing to the development of Harlaa as a locus of cosmopolitanism.

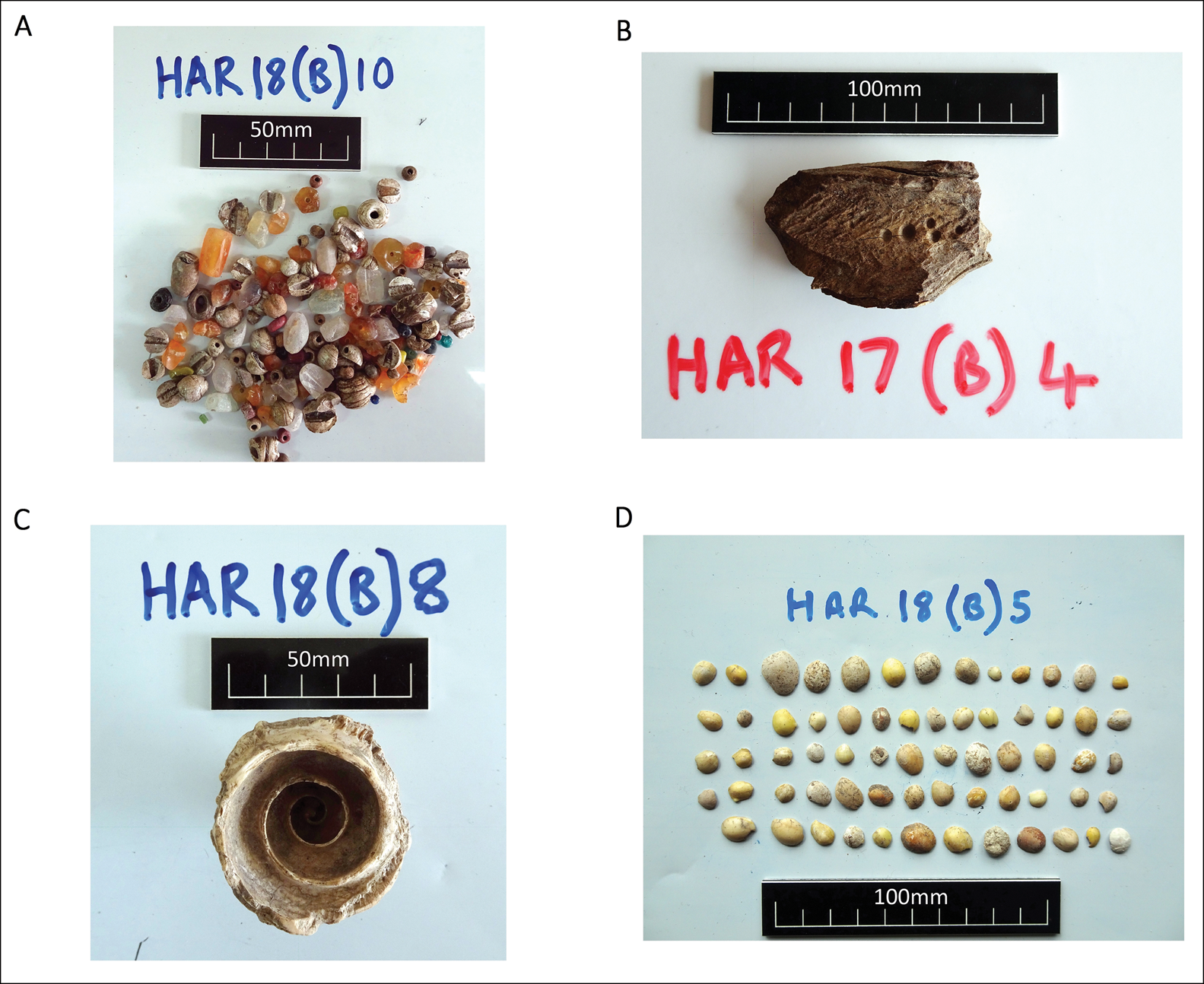

Imported materials are well represented. Beads appear to have been an important commodity at Harlaa, with evidence for agate, glass and shell bead-making, evidenced in particular in the workshop complex, from which 1952 of a site total of 2441 beads were recovered (Table 2). The majority of the beads (approximately 2000) are made of glass (Figure 5A). Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) analysis of four beads from the workshop complex indicates the importation of some beads from Central Asia, the Middle East (possibly Mamluk Egypt) and Sri Lanka/South India (Dussubieux Reference Dussubieux2018). Others may have been locally made, as suggested by the presence of possible glass-bead wasters, but this awaits confirmation. Initial portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis of four crucible fragments (of a total of 216) from the workshop complex demonstrates that one contained traces of a copper-based colourant, possibly resulting from the processing of blue glass beads (Santarelli & Rehren Reference Santarelli and Rehren2018). Glass beads, including blue glass, are extensively found in medieval non-Muslim contexts in eastern, southern and central Ethiopia, such as at Koticha Kesi, which was abandoned c. 1550, eighth- to twelfth-century Nora, Raré and Sourré-Kabanawa, and ninth- to fourteenth-century Meshalä Maryam and Tätär Gur (Joussaume Reference Joussaume1980, Reference Joussaume2014; Fauvelle-Aymar & Poissonnier Reference Fauvelle-Aymar and Poissonnier2012, Reference Fauvelle and Poissonnier2016; Kinahan Reference Kinahan2013; Fauvelle-Aymar et al. Reference Fauvelle-Aymar, Hirsch and Chekroun2017). Some of these glass beads may have been from Harlaa, and our next phase of research will focus on the analysis of their composition to assess whether they match the known beads from this site.

Table 2. Distribution of examples of luxury materials from Harlaa (beads can be both locally made and imported; all other materials listed are imported).

Figure 5. Beads and shell: A) examples of glass, quartz and agate beads; B) bow-drill hand-guard made from a large equid femur; C) Strombus tricornis end whorl, cut off during bangle manufacture; D) dorsa from Monetaria moneta and Monetaria annulus cowry shells (photographs by T. Insoll).

Approximately 400 other beads found at Harlaa were of agate and quartz (Figure 5A). The agate bead-making traditions resemble those of Gujarat in western India (see Kenoyer et al. Reference Kenoyer, Vidale and Bhan1991; Roux Reference Roux2000; Bhan et al. Reference Bhan, Kenoyer, Vidale and Kanungo2017), in their use of heat-treated carnelian, bow drilling and diamond drill bits (see Kenoyer Reference Kenoyer and Kanungo2017). The heat treatment of agate at Harlaa is indicated by both orange and red (treated) and white (untreated) agate in debitage, part-finished beads and finished bead forms. LA-ICP-MS analysis of four samples of agate debitage and bead fragments from Harlaa indicates varied sources, with two from Mandek Bet and Ratanpur in Gujarat, one from Shahr-i-Soktar in Iran and the other from an unknown source (Dussubieux Reference Dussubieux2018). Bow-drill use is directly attested by a discarded hand-guard made from part of a femur of a large equid, with five holes (2.20–4.30mm in diameter) on its underside made by the drill spindle (Figure 5B). Double diamond drill-bit use is also confirmed by dental-moulding paste impressions of drill holes in part-finished and discarded agate beads (J.M. Kenoyer pers. comm.).

Shell-working was another major activity at Harlaa. An assemblage of 2385 worked and unworked marine shells and shell fragments, and six shell beads, was recovered from Harlaa, with the majority—comprising 1748 worked and unworked marine shells and shell fragments, and four shell beads—coming from the workshop complex. All the shell species found were available from the Red Sea, approximately 120km east of Harlaa, suggesting that a hitherto largely unrecognised supply source was available (Insoll Reference Insoll2021b). The shell was worked in several ways: into short and long bicone beads from Strombus tricornis; pierced for adornment (Monetaria moneta, Monetaria annulus, Oliva bulbosa and Engina mendicaria); cut into fragments (O. bulbosa, Conus erythraeenis and Anadara antiquata); and made into bangles (S. tricornis) (Figure 5C) (Insoll Reference Insoll2021b). The bangle-manufacturing is similar to that recorded in sixth- to twelfth-century contexts at Mantai in Sri Lanka, with the same sawing of the shell ends to remove circular sections and the discarding of broken, sawn shell rings (see Waddington & Kenoyer Reference Waddington, Kenoyer, Carswell, Deraniyagala and Graham2013: 386), although Turbinella pyrum was used at Mantai, not S. tricornis. The piercing of the predominantly cowry material at Harlaa relates to a ubiquitous, sub-Saharan method of processing such shells for stringing and sewing (e.g. Haour & Christie Reference Haour and Christie2019: 305–306). At Harlaa, however, this appears to have been achieved using an Indigenous technology—obsidian blades—with the 1352 dorsa recovered from the site indicating this process (Figure 5D).

Access to raw materials seems to have been crucial at Harlaa and may explain the location of the settlement. Extensive mines have been identified at the top of the mountain opposite Harlaa, Gara Harfattu (1888m asl; 9°29′46.212″ north, 41°54′22.68″ east). These mines comprise both vertical and horizontal shafts, a technique for following mineral veins known in other contemporaneous Islamic contexts (al-Hassan & Hill Reference al-Hassan and Hill1992: 236). The vertical shaft entrances appear to have been reinforced with stone blocks. The horizontal gallery entrances may have been similarly reinforced, but this awaits confirmation pending specialist analyses of the mining complexes. The material mined is also currently unknown. Ceramic sherds collected from the surface suggest that the mining complex was potentially contemporaneous with Harlaa at its zenith between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Other types of imported finished goods were also recovered. Glass-vessel fragments are generally small, monochrome and undecorated, and in various colours, including clear, blue, green, brown, purple and yellow. LA-ICP-MS analysis of five fragments suggests a possible Central Asian provenance, based on their v-Na-Al, high alumina soda plant-ash glass composition (Dussubieux Reference Dussubieux2018). The assemblage of 171 sherds of Middle Eastern ceramics (Table 2) also features varied types. Those that can be more precisely identified date to the eleventh/twelfth to fourteenth/fifteenth centuries and include: 22 sherds of white, purple, red, light green and yellow, lustrous silvery grey, black, and turquoise glaze wares—all likely from bowls, and probably of Yemeni/southern Red Sea provenance (S. Priestman pers. comm; see Cuik & Keall Reference Cuik and Keall1996) (Figure 6A); 25 sherds of black-on-yellow or ‘mustard’ ware bowls of Yemeni provenance (see Lankester Harding Reference Lankester Harding1964: pl. V.10; Horton Reference Horton1996: 291) (Figure 6B); three sherds of silver lustre-glazed frit, and one turquoise monochrome-glazed frit sherd—all of Iranian provenance (Figure 6C). Additionally, four sherds of Indian Red Polished ware were found (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Imported Middle Eastern and South Asian ceramics: A) degraded lustrous white-glazed rim of probable Yemeni origin (HAR19-B-10.2) (not drawn); B) black-on-yellow Yemeni rim (HAR15-B-8.5); C) off-white lustrous-glazed scalloped rim fragment, Iranian frit (HAR19-E-25.4); D) Indian Red Polished-ware rim (HAR19-E-24.1) (photographs by N. Tait).

Ceramics from farther east include 160 sherds of Chinese and Southeast Asian/Chinese origin (Table 2). Fifty-seven of these sherds are from ‘Martaban’ storage jars (Figure 7A), with 51 recovered from the domestic building and six from the workshop complex. At least two different jar types are present at Harlaa, potentially suggesting multiple sites or dates of manufacture (eighth to late fourteenth centuries). Of the remaining 103 sherds, 93 are green-glazed, the majority are classic celadon types from the Longquan kilns in Zhejiang, south-eastern China (eleventh to late fourteenth centuries). Others include Yaozhou ware from the Yaozhou kilns, Shaanxi, northern China (tenth to twelfth centuries), possible Yue ware from Shanglinhu, Zhejiang, southern China (tenth to eleventh centuries) and Guangdong Celadon Group 1 (GDC.1 after Priestman's (Reference Priestman2013: 666) classification) from Guangdong, southern China (Figure 7B) (late thirteenth to fifteenth centuries). Four sherds are probably from the Dehua Kilns, Fujian, southern China (Figure 7C) (eleventh to thirteenth centuries); three white glazed and one grey glazed are as yet uncategorised. All identified forms are from dishes, predominantly bowls and some plates (0.11m–0.27m diameter), apart from the ‘Martaban’ sherds, which are from jars. Unusually, 55 of the 160 sherds exhibit clear evidence of modification, and a further 15 are possibly modified. This modification is principally in the form of sherds being shaped into rounded discs or into polygons (Figure 7D), potentially intended to be set in jewellery, as bezels, or sewn into clothing (Insoll et al. Reference Insoll, Khalaf, Maclean and Zerihun2017: 38). Thus, imported Chinese ceramics were being modified to suit local tastes.

Figure 7. Imported Far Eastern ceramics: A) Martaban storage jar (HAR18-E-7a); B) Guangdong celadon (HAR17-B-10a); C) possible Dehua whiteware (HAR15-B-8d); D) celadon disc (HAR19-E-6a) (photographs by H. Parsons-Morgan).

Other imported artefacts, such as glass wares, were consumed, unaltered, at Harlaa. Still other categories of object were being manufactured to meet (presumably) regional demand, such as Indian-style agate beads, South-Asian-style shell beads and bangles, and, possibly, glass trade beads. Harlaa was a cosmopolitan hub with merchants, carriers, consumers, craftspeople from different regions, ethnicities and traditions. These individuals serviced varied tastes and exchanged not only goods and commodities, but also knowledge and beliefs.

Islam, Islamisation and other religions

Muslim belief was a key part of this cosmopolitan interchange. The establishment of a Muslim community at Harlaa, the earliest in eastern Ethiopia, can be reconstructed on the basis of the AMS dates from the mosque and burials, the former in existence by the mid twelfth century. Additional confirmation is provided by Arabic inscriptions, with one exhibiting a date of 657 AH (AD 1259–1260) (Bauden Reference Bauden2011: 296), and another featuring the partial date of 44x AH (Schneider Reference Schneider1969: 340), calculated as AD 1048–1057 (Chekroun et al. Reference Chekroun, Fauvelle-Aymar, Hirsch, Ayenachew, Zeleke, Onezime, Shewangizaw, Fauvelle-Aymar and Hirsch2011: 79). A further nine undated Arabic inscriptions have been recorded during recent fieldwork. Eight appear to be funerary inscriptions, as indicated by the choice of Qur'anic verses cited on some examples, a common occurrence in funerary settings (J. Loiseau pers. comm.) (Figure 8). The ninth Arabic inscription, as yet undecipherable, was incised into a soft-stone jewellery mould.

Figure 8. Funerary inscription with part of Qur'an 55: 27. This is usually quoted with Qur'an 55: 26 to read, “Everyone on earth perishes; all that remains is the Face of your Lord, full of majesty, bestowing honour” (Qur'an 55: 26–27) (photograph by T. Insoll, translated by J. Loiseau).

The early evidence for Islam at Harlaa suggests that the settlement was a context for conversion, and from here Islam spread throughout the wider region via trade and other interactions. Harlaa was seemingly abandoned by the early fifteenth century, and Harar, the most important extant Islamic city in Ethiopia, was founded, or at least Islamised, after this date by the descendants of the people of Harlaa. Excavations in settlement areas (e.g. Gey Hamburti and the Amir's Palace) and mosques in Harar (e.g. Abdal mosque, Aw Abadir shrine, Aw Meshed mosque, Dine Gobena mosque, Fakhredine mosque and shrine, Jami mosque) indicate that they were all established after the late fifteenth century (Insoll & Zekaria Reference Insoll and Zekaria2019). The results from Harar suggest a direct chronological link with Harlaa and affirm the continued importance of the urban environment as a context for Islamic conversion, as the city was to have a significant impact in furthering the Islamisation of the surrounding Oromo population (Insoll Reference Insoll2017; Insoll & Zekaria Reference Insoll and Zekaria2019).

At Harlaa, Islam co-existed with Indigenous religions that were followed by the majority of the local population. The nature of these religions is little understood, as they left no historical records and have only been partially investigated archaeologically with reference to their most tangible aspect: funerary practice. No evidence for Indigenous religion has yet been found in Harlaa, unless dietary remains indicate such. Some of the non-Muslim funerary monuments—the stone cairns or tumuli (Daga Tuli), sometimes with circular burial chambers—that are found in the Tchercher Mountains, however, are contemporaneous, as is Sourré-Kabanawa, 40km to the south-west of Harlaa, where two such tombs have been radiocarbon dated to cal AD 980–1180 (monument one), and cal AD 770–950 and cal AD 930–1080 (monument three) (Joussaume Reference Joussaume1980: 102). To the east of Harar, non-Muslim burials persisted even later, with an AMS date of cal AD 1275–1385 (2σ calibration; Beta-421104) obtained from charcoal from a burial mound excavated at Sofi, near Ganda Harla (Insoll et al. Reference Insoll, Maclean and Engda2016: 30).

It is unknown whether Christians also formed part of the cosmopolitan population at Harlaa, although there are suggestions that contacts were maintained with Christian communities at Harlaa, and, historically, Muslims were traders in Christian areas (Ahmed Reference Ahmed1992: 20). A copper coin, a Byzantine trachy of the Emperor Theodore Komnenos Doukas (1224–1230) minted at Thessaloniki, was recorded as a surface find at Harlaa (Figure 9). No such coins have previously been found outside of the southern Balkans, southern Greece, southern Italy or western Anatolia, and it is possible that this example reached Ethiopia via Egypt (J. Baker pers. comm.). Another surface find from Harlaa is a single sherd of Egyptian Red Slip ware—a variant of African Red Slip Ware, manufactured at Aswan, and of possible fifth-century date (D. Mattingly pers. comm.). This suggests much earlier contacts with an area of Africa that was then Christian.

Figure 9. Byzantine trachy of the Emperor Theodore Komnenos Doukas (1224–1230): A) obverse; B) reverse (photographs by T. Insoll, identification courtesy of J. Baker).

Towards understanding the population of Harlaa

The population of Harlaa was probably part Muslim and part non-Muslim, with both groups comprising local and non-local components. The identities of the non-local individuals are currently unknown, but it can be suggested, based on the evidence discussed above, that these could have included Arabs, Indians, Persians and any number of groups from the wider region, such as Somali and perhaps Swahili. Strontium isotope analysis of human teeth from three Muslim burials from Harlaa suggest varied origins. The upper burial from a double grave (HAR-C)—a child aged 2.5–3.5 years at death—has strontium isotope ratios in deciduous teeth that are indistinguishable from the general Harlaa range (Pryor et al. Reference Pryor, Insoll and Evis2020), indicating that the infant and pregnant mother had lived in the area. The lower burial, a child aged 4.5–6.5 years at death, has strontium isotope ratios that are also indistinguishable from the local Harlaa range. A third single burial (HAR-D), another child aged 2.5–6.5 years at death, has a different strontium isotope ratio, suggesting that they were non-local (Pryor et al. Reference Pryor, Insoll and Evis2020).

It is likely, however, that the majority of the population at Harlaa came from the local area. The ceramic data suggest interaction with the local population or, more likely, the presence of a local population at Harlaa using ceramics with which they were familiar. Some 20 534 sherds of locally made pottery have been recovered, compared with 331 sherds of imported pottery (Tait Reference Tait2020). All the local ceramics are handmade and appear to have been fired in open bonfires. They have a similar fabric composition, with poorly sorted, coarse inclusions up to 1mm in size, and rarer larger inclusions up to 5mm. While a source has yet to be identified, these ceramics appear to have been produced using local clays. Earthenware/plainware (Figure 10A), usually red, comprise the largest proportion of wares (9725 sherds; 77.8 per cent), with black/brown burnished wares also relatively common (2250 sherds; 18 per cent), followed by light brown (369 sherds; 3 per cent) (Figure 10B). Other wares include black slipped with a red fabric (58 sherds; 0.5 per cent) and light brown slipped with a black fabric (nine sherds; 0.1 per cent) (Tait Reference Tait2020). Only 380 sherds (2.46 per cent) are decorated. Incised decoration (125 sherds; 32.9 per cent of decorated sherds) of simple horizontal lines or rows of dashes, or punctate (dot) decoration (73 sherds; 19.5 per cent) feature on all ware types. The most common decorative style (140 sherds; 36.8 per cent) is roughened line decoration, consisting of straight or zig-zag lines added to burnished wares after burnishing, but prior to firing (Figure 10C). The significance of this technique is unclear.

Figure 10. Examples of locally made ceramics: A) large red/brown earthenware/plainware storage vessel with flat in-turned rim (HAR17-B-6-27); B) light brown burnished carinated bowl with simple rim (HAR17-B-18-8); C) black/brown burnished simple rim with roughened line decoration (HAR17-B-14-2); D) earthenware/plainware stand base (HAR15-A-2-6); E) black/brown burnished bowl with simple rim and grooved decoration (HAR17-B-5-8) F) black/brown burnished out-turned flat-lipped rim with roughened line decoration (HAR17-B-8-6) (photographs by N. Tait).

Vessel forms included carinated bowls (Figure 10B), bowls, jugs and jars with ring bases, large storage vessels (Figure 10A) and bowls with multiple legs attached to a flat plate or ring—so-called ‘stand bases’ (Figure 10D). Nine broad-rim categories have been identified, with simple (656 sherds; 40.9 per cent) (Figure 10C & E) and flat (459 sherds; 28.6 per cent) rims (Figure 10A & F) being the most common (Tait Reference Tait2020). Affinities exist with ceramic assemblages from both non-Muslim and Islamic sites. Carinated bowls and globular-bodied jars from Harlaa are of types also found at the Raré and Sourré-Kabanawa burial tumuli in the Chercher Mountains (Joussaume Reference Joussaume1980: 102, Reference Joussaume2014: 103–104), and pierced lug handles and grooved- and pricked-rim decoration resemble local ceramics from medieval Islamic town-sites in Somaliland, on the trade route from Harlaa to the Red Sea coast (see Curle Reference Curle1937; González-Ruibal et al. Reference González-Ruibal, de Torres, Franco, Ali, Shabelle, Barrio and Aideed2017).

The edible crops identified at Harlaa, such as Hordeum sp. and Triticum sp., are suggestive of further population complexity. Crop remains that are local to Ethiopia, such as Teff (Eragrostis tef) and finger millet (Eleusine coracana), are notably absent. This situation is comparable with cultural development in northern Ethiopia, where the contemporaneous agricultural system was dominated by the cultivation of wheat, barley, legumes (e.g. Pisum abyssinicum, Lens culinaris, Cicer arietinum) and oil crops (e.g. Sesamum indicum, Linum usitatissimum), all of Middle Eastern origin (Beldados et al. Reference Beldados, Zewdu and Insoll2019). Zooarchaeological evidence also supports the existence of a cosmopolitan religious community or religious non-observance; warthog (Phacochoerus sp.) or bushpig (Potamochoerus sp.) would not likely have been consumed by observant Muslims. At Harlaa, the proportions of goat, cattle and sheep elements, along with the butchery evidence, resemble those found at multiple Islamic-period sites in Arabia, Mesopotamia and Iberia (c. eleventh to sixteenth centuries). This also suggests the presence of individuals at Harlaa who followed a more orthodox Muslim diet (Gaastra & Insoll Reference Gaastra and Insoll2020).

Conclusions

The evidence from Harlaa, be it glass, burials, faunal remains, inscriptions, architecture, technology or ceramics, confirms the emergence of cosmopolitanism through a translation of cultural difference. As Richard (Reference Richard2013: 44) has described for Senegambia in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, such translation occurs through

regular economic, social, and interpersonal encounters with people who were culturally foreign; the habitual adoption and circulation of far-away goods and distant ideas; and the development of new cultural forms and material practices in the realm of architecture, foodways, and religion.

The newly acquired archaeological data may enable recognition of cosmopolitanism, but it remains difficult to identify Harlaa within the possible descriptions and references in the limited corpus of medieval Arabic sources. These texts range from al-Ya‘qūbī (d. 897) to al-Maqrīzī (fourteenth century) (e.g. Vantini Reference Vantini1975; Huntingford Reference Huntingford and Pankhurst1989: 76–77), but are mostly based on second-hand observations, which are repetitive and concerned with the Red Sea coast, rather than the Ethiopian interior (Ahmed Reference Ahmed1992: 23; Insoll Reference Insoll2021a). These challenges notwithstanding, the most probable conclusion is that Harlaa was Hubät/Hobat, the capital of the Hārlā sultanate. Hubät/Hobat was described by Stenhouse (Reference Stenhouse2003: 69) as a “small tributary territory east of Šawā (Shoa), affiliated to Ifat”, one of the much larger medieval Ethiopian, Islamic polities (c. 1286–1435/36). Topography appears key in the identification of Harlaa. Said Shihad Hussein (pers. comm.) has made the inspired deduction that the Somali word hoobat and the Arabic hubuut could refer to the location of Harlaa, as both of these words mean to descend a slope from an upland point; that is, a reference to the mid-point between the highland and the lowland—exactly where Harlaa is located. Thus, the move from the recognition of cosmopolitanism to “identifiable histories” (Richard Reference Richard2013: 59; emphasis in original) can be made, with the archaeological evidence indicating that Harlaa/Hubät/Hobat was central within the complex processes of identity negotiation both within medieval Ethiopia and the wider Islamic and non-Muslim worlds.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Authority for Research and Conservation of Cultural Heritage, Addis Ababa, the authorities in Dire Dawa and the administrators and community in Ganda Biyo for approving the research; to Seth Priestman, Stéphane Pradines and Robert Mason for initial comments on the glazed ceramics; to Brunella Santarelli, Thilo Rehren and J. Mark Kenoyer for undertaking aspects of the archaeometric and material analyses; and to Said Shihad Hussein for sharing his observation on Harlaa.

Funding statement

The European Research Council is thanked for funding the project (grant ERC-2015-AdG BM694254).