Dear Editor,

A recent focus has been placed on prescribing practices, particularly of antipsychotic medication, in Irish CAMHS services, by the Maskey Report (Reference Maskey2022) and subsequent Mental Health Commission Report (2023). This has led to high profile discussions at a national level within the health service, government and media. The issues raised regarding safety of clinical care in CAMHS are likely to have significantly impacted confidence and trust in CAMHS for many young people and families attending these services. In order to improve clinical care and restore public confidence in CAMHS services, it is essential that appropriate prescribing and monitoring guidelines, protocols and frameworks are developed and implemented at both local and national levels. The CAMHS Connect Team based in CHO2 (Co. Galway, Co. Mayo & Co. Roscommon) wish to share with your readers their experience of introducing a nurse-led physical health monitoring service.

A steering group was established across CHO2 CAMHS services to review antipsychotic prescribing and monitoring practices.

Investigations and monitoring (including blood tests and ECGs) have typically been completed by GPs at the request of the prescribing doctor in CAMHS. In the absence of an integrated electronic record system, this communication is largely paper based and is hampered by high clinical workloads in both CAMHS and primary care.

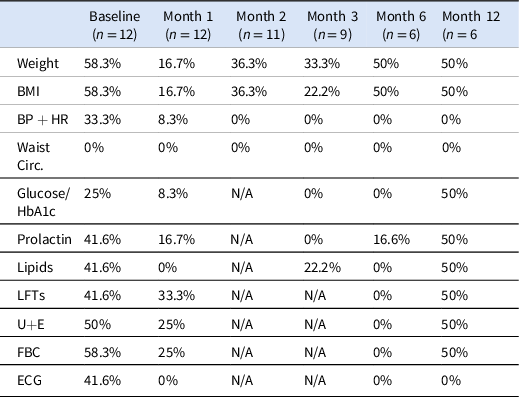

An initial audit of antipsychotic monitoring was completed within one community CAMHS team. The rate of prescribing within this team was low with only 12 patients (1.7%) prescribed antipsychotic medication from a total caseload of approximately 700. Overall compliance with monitoring was poor (Table 1).

Table 1. Audit of compliance with physical monitoring (before physical health clinic)

A survey of prescribing doctors in CHO2 community CAMHS services identified time constraints and communication with other services as the most frequent barriers to compliance with monitoring. Feedback from prescribers indicated a consensus that physical health monitoring of young people prescribed antipsychotic medications by CAMHS teams is the responsibility of the CAMHS service.

The steering group proposed a plan to establish a nurse-led, centralised physical health monitoring clinic within the CAMHS Connect, Day Hospital Service. This clinic, based across two sites, would be offered to all young people attending the six community CAMHS teams in CHO2 prescribed antipsychotic medication.

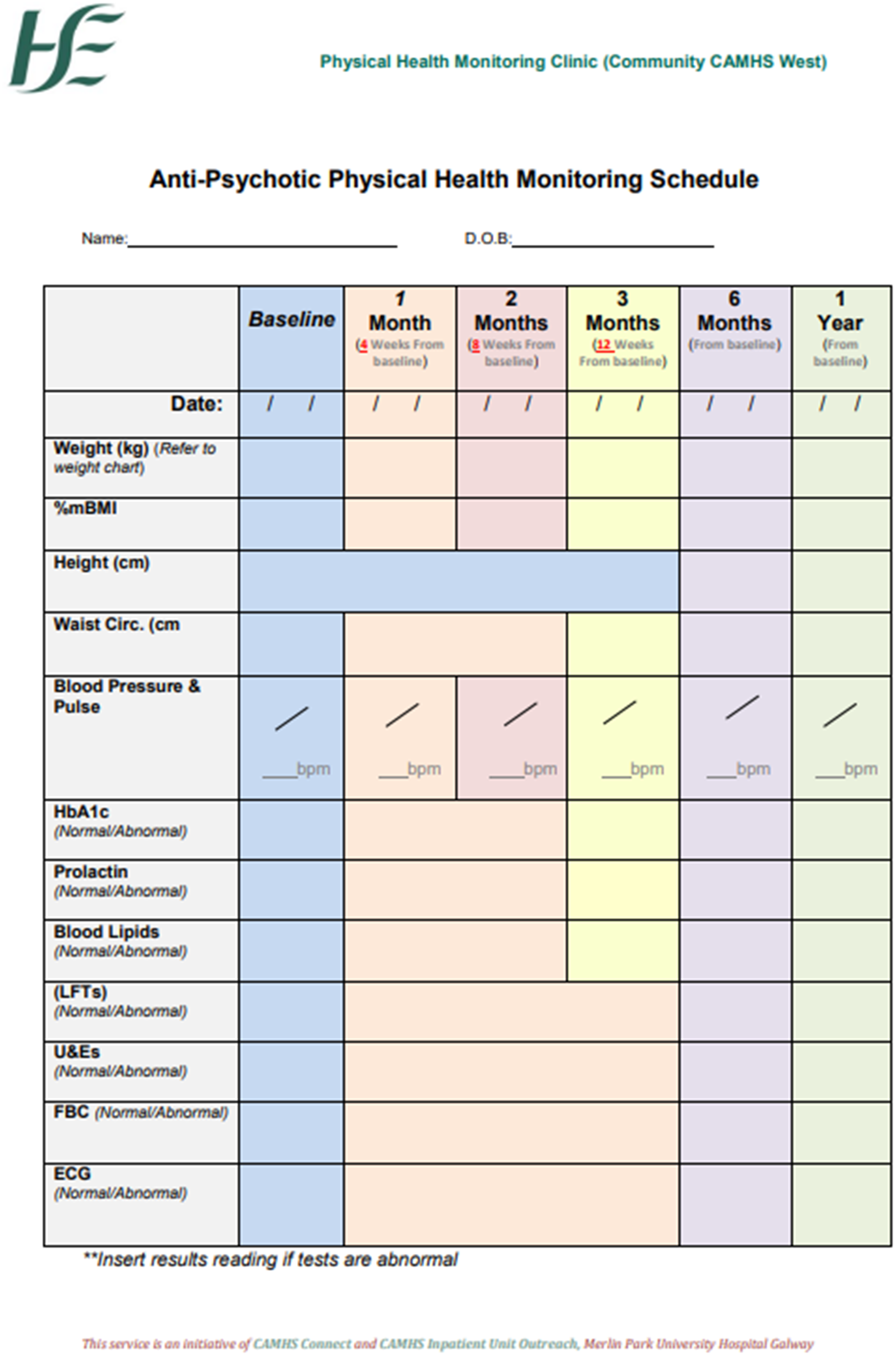

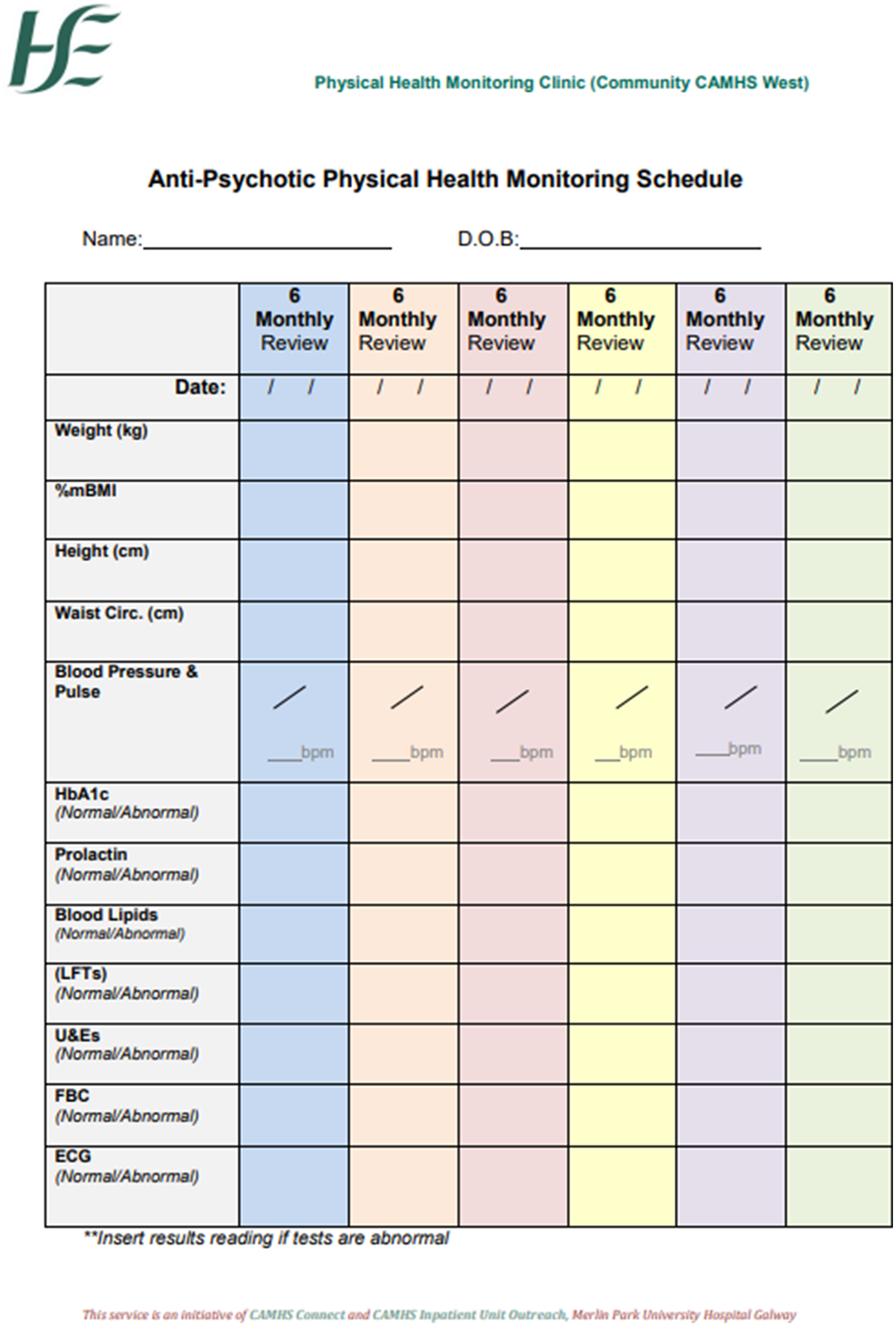

There was no established local protocol for monitoring of antipsychotic medications in community CAMHS. A protocol had been developed and was in use within the local CAMHS inpatient unit. This protocol was reviewed against the NICE guidelines by the steering group to ensure compliance with evidence based, international best practice. For all parameters, the monitoring recommended by this protocol was at least as frequent as the NICE guidelines. As research has demonstrated that children and adolescents are at increased risk of side effects, it was decided to err on the side of more frequent monitoring as set out in this protocol (Libowitz and Nurmi Reference Libowitz and Nurmi2021). An adapted version of the inpatient protocol was agreed for use in the clinic, supporting equity of care between young people prescribed medication in the community and those receiving treatment in an inpatient setting.

Initial assessment appointments included completion of side effect rating scales, blood tests, ECG and physical parameters. Patients were also provided with psychoeducation on antipsychotic medication and side effects. Follow-up appointments were offered in line with the monitoring protocol. By completing all monitoring during one point of clinical contact, the service minimised the number of appointments that families need to attend, removed any ambiguity regarding responsibility for monitoring and minimised and streamlined communication between clinicians and services.

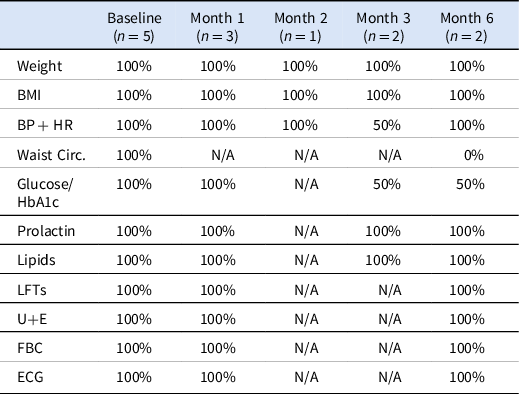

Since the clinic commenced, there was a steady rate of referrals with 51 patients attending in total. The clinic experienced a high rate of non-attendance with 28 missed appointments in total, with most of these accounted for by a small number of attenders. The clinic did not implement a policy of discharge based on non-attendance. Following a missed appointment, parents were contacted to arrange a new appointment time. Following two missed appointments, the treating team were informed and requested to encourage attendance. This policy resulted in monitoring being facilitated for all patients referred within the time frame set out by the clinics protocols. While requiring considerable input of time, the benefit of this has been captured in our re-audit of compliance which has indicated a substantial improvement in monitoring, with most parameters being recorded with 100% compliance (Table 2).

Table 2. Audit of compliance with physical monitoring (following physical health clinic)

Feedback forms were provided to parents and young people attending the clinic. Feedback indicated that all parents had a high level of satisfaction in terms of accessibility, clarity of communication and information as well as perceived benefit for their child and confidence in the service provided. Young people were equally likely to feel that they had benefited from attending the clinic and most reported improved knowledge of side effects and confidence in recognising these, as well as improved understanding of the importance of managing their physical health.

In this pilot project, we have implemented a framework for physical health monitoring of young people prescribed antipsychotic medication across CHO2. Our preliminary review suggests that this service is feasible and acceptable to clinical staff, patients and families as well as improving compliance with best practice of side effect monitoring.

The team has commenced data collection for an outcome study exploring detection of side effects and clinical outcomes for young people attending the service.

The service continues to expand in both its remit and the geographical area serviced. A new satellite clinic is planned in Co. Mayo to increase accessibility for patients and families, and the service will begin to offer lithium monitoring for young people attending CAMHS across the CHO2 area.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our gratitude to the parents and young people who participated in this pilot project. We also acknowledge the work of the Merlin Park CAMHS inpatient team who developed the monitoring guidelines on which the protocols in this project are based. Additionally, we acknowledge the contribution of all members of the steering group who contributed to the design and development of the physical health monitoring clinic.

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1