We knew. There was no need to hurry. It was too soon to generalize. First of all, we must see as much as possible.

Every detail of the adventure sounds implausible. In 1935, two Soviet humorists undertook a 10,000-mile road trip from New York to Hollywood and back, accompanied only by their guide, a gregarious Russian Jewish immigrant, and chauffeur, his Russian-speaking, American-born wife. That the Soviet Union under Stalin even had humorists will come as a surprise to many. But Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov were genuine Soviet funnymen, the coauthors of two beloved satirical novels, The Twelve Chairs (1928) and The Little Golden Calf (1931). Even more surprising for those looking back through the prism of Cold War hostility, neither the FBI nor the Soviet political police (the NKVD) seems to have restricted the freewheeling trip.Footnote 1

Ilf and Petrov arrived in the United States at a moment of hopeful transition. The famine and shortages caused by the collectivization of agriculture and Stalin’s crash industrialization program (the First Five-Year Plan, 1928–1932), had eased. During the “three good years” of the decade, 1934–1936, life for Soviet citizens was better if not quite, as Stalin famously asserted, more joyous.Footnote 2 The booming Soviet economy offered an optimistic contrast to the West suffering through the Great Depression. In the arts, the method of socialist realism had yet to be rigidly codified. In the realm of foreign affairs, the Soviet state’s 1933 establishment of diplomatic ties with the United States appeared to presage more open relations with the West. Indeed, the trip seemed designed to promote friendly cultural exchange.

By the time Ilf and Petrov published their account of their American travels, the good years had ended. The August 1936 show trial of Stalin’s political opponents produced more than a dozen death sentences and a paroxysm of xenophobia. The Great Purges of 1937–1938 often targeted cultural and political elites, who accused each other of ideological failings and participation in vast and far-fetched conspiracies involving foreign intelligence agencies. Supposedly implemented to root out hidden enemies who might organize a lethal fifth column in the event of war, the purges coincided with mounting distrust of friendly, or indeed any relations with the capitalist world.

Thus, the most mindboggling feature of Ilf and Petrov’s adventure is the fact that in 1937, at the height of the Stalinist terror, when any sort of connection to foreigners raised suspicions of treason or espionage, their American travelogue was published in both the Soviet Union and the United States.Footnote 3 Despite the grim political climate, their photo essay “American Photographs” and their book Odnoetazhnaia Amerika (Low-Rise America, literally One-Story America) reached a wide and appreciative Soviet audience. The title referred to the writers’ interest in finding the “real” America of low-rise buildings beyond the skyscrapers of New York. To capitalize on the American success of The Little Golden Calf, the US publisher substituted Little Golden America for the clunky “one-story America.” Under the circumstances, the American title with its golden spin on the land of capitalism was unfortunate. But it was not wholly inaccurate. The America Ilf and Petrov described was at once the spiritually impoverished antithesis of the socialist utopia under construction in the USSR and, even during the Great Depression, a phenomenally rich model of efficiency and modernity.

Taking Ilf and Petrov’s adventure as a point of departure, this book tells the story of Soviet–American relations as a road trip. While there is a vast historical literature on the interwar “pilgrimage to Russia” that Michael David-Fox deems “one of the most notorious events in the political and intellectual history of the twentieth century,” historians have paid relatively little attention to travel in the opposite direction.Footnote 4 Interwar trips to Russia came to seem particularly “notorious” because they were managed and monitored by the Soviet state with the apparent aim of persuading – if not “duping” – Western visitors, especially intellectuals, into supporting the Soviet system. Not incidentally, the state’s role in cultural diplomacy has left historians a vast and centralized archive from agencies such as VOKS (the All-Union Society for Cultural Ties Abroad) that offers a window into the Soviet side of these exchanges.

By contrast, in the interwar years, the United States government had little involvement in cultural diplomacy beyond the basic regulatory task of issuing visas. For the historian, this situation offers an opportunity to push the history of cultural diplomacy beyond its traditional focus on state initiatives (such as VOKS) by exploring how a variety of nonstate actors shaped cultural relations. However, the fact that the US government did not guide or systematically track Soviet visitors also means that the archival records of their activities are fragmented and incomplete.

Retracing Ilf and Petrov’s American road trip offers an innovative and fruitful means of locating the widely scattered individuals engaged in building friendly relations. To a degree unacknowledged in their published accounts, the writers relied on immigrants, communists, and fellow travelers as hosts, guides, and translators. Following the clues in their notes and letters, I identified many of these intermediaries. Their stories not only open new perspectives on Ilf and Petrov’s American adventures, they also illuminate the understudied question of how Soviet travelers in the United States interacted with immigrant communities and allow us to understand how ordinary people became creative actors in cultural exchanges.

Because Ilf and Petrov were famous writers who met with prominent American authors, artists, and critics, many of their exchanges involved “culture” in the narrow sense. Investigating their adventures, I was able to flesh out cultural studies scholars’ references to the transnational networks that linked Soviet and American modernists.Footnote 5 My reconstruction of Ilf and Petrov’s encounters with American cultural producers, including the novelists John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway, as well as Russian and Jewish immigrants working in Hollywood, reveals the personal, multidirectional, and contingent nature of cultural exchange.

The book also examines culture in the broader sense, addressing the fundamental question of whether and how cross-cultural understanding happens. Under what conditions can interactions with other cultures and other people become mutually transforming experiences? Work on Western travelers in the Soviet Union proposes that their visits “triggered a process of intense mutual appraisal.”Footnote 6 By contrast, much of the scholarship on Russian travelers in the United States suggests that such contacts produced little self-reflection, let alone transformation. The historian Meredith Roman argues that Soviet visitors were more concerned with signaling their “superior racial consciousness” than in questioning their stereotypes of African Americans as “naturally gifted dancers, musicians, and performers.”Footnote 7 Literary studies of Russian American travelogues, including Ilf and Petrov’s, emphasize that they relied less on “firsthand impressions” than “the framework imposed by literary tradition.” Quoting Ilf and Petrov’s assertion that they “glided over the country, as over the chapters of a long, entertaining novel,” Milla Fedorova concludes that “the travelers read America rather than saw it.” They were less interested in making discoveries than in confirming their view of their own country and themselves in the mirror of a mythical Other.Footnote 8 Without minimizing the power of the literary, ideological, and cultural preconceptions that prompted a particular “reading” of America, I focus on the complex task of translating American people, places, and practices into Soviet terms.Footnote 9 Drawing on sources from both sides, I examine specific encounters between the Soviet tourists and the “natives” as a means of assessing the process and possibility of questioning or even reshaping presuppositions about the Other.

Ilf-and-Petrov

Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov shared roots in Odesa, a bustling, cosmopolitan port on the Black Sea. The only city in the empire to which Jews could move without special permission, Odesa had a reputation for rogues, wit, and irreverence.Footnote 10 Ilf, born Ilya Arnoldovich Fainzilberg in 1897, was Jewish, the son of a bank clerk. Petrov, born Evgeny Petrovich Kataev in 1903, came from more elevated circumstances as the son of a lycée teacher. He took the pen name Petrov to distinguish himself from his older brother Valentin Kataev, already an established writer. In 1923, Ilf and Petrov moved separately to Moscow, where both eventually became writers at Gudok (The Steam Whistle), the railway workers’ newspaper that employed Kataev and other writers who became major literary figures: Isaac Babel, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Yuri Olesha.Footnote 11

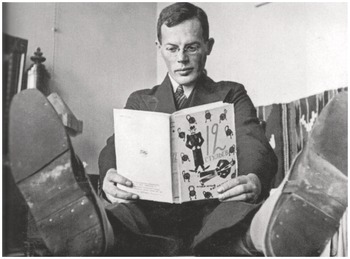

The writers began their partnership in 1927. According to Kataev, he proposed the treasure hunt story that became their first collaboration, The Twelve Chairs, a cross-country search for diamonds hidden in one of twelve dining room chairs dispersed by the Revolution. Ilf and Petrov, writing each sentence together, quickly finished the novel. It was an immediate success among readers, who took to its hero, the “smooth operator” Ostap Bender. Out to make a fortune in the not fully socialist Russia of the 1920s, Bender got his throat cut at the end of the story. But the con man proved so popular that Ilf and Petrov resurrected him for their second novel, The Little Golden Calf, which took Bender on another road trip. This time he and his sidekicks stalked an underground Soviet millionaire, whose riches Bender hoped to appropriate. (Figures 0.1 and 0.2)

Figure 0.1 Ilya Ilf reading the book The 12 Chairs, c. 1930.

Figure 0.2 Evgeny Petrov reading the English edition of The Little Golden Calf, c. 1930.

Thus, the writers became the much-loved single entity Ilf-and-Petrov. By the early 1990s, print runs of their novels ran to over 40 million copies.Footnote 12 In the 1930s, English translations found enthusiastic readers in the United States. When Ilf and Petrov met Upton Sinclair, he told them that “he had never laughed harder than when reading The Little Golden Calf.”Footnote 13 In the United States, the two writers were sometimes referred to as the “Soviet Mark Twain.” They seemed to appreciate the irony of the nickname and played up their kinship with the American funnyman.Footnote 14 Via an interpreter, Petrov told reporters from the New Yorker that “It is because life is so tragical that we write funny books.” His mention of the pair’s visit the previous day to the Mark Twain house in Hartford, Connecticut, prompted a grinning Ilf, the more reserved and sardonic of the two, to chime in with the assertion “that Mark Twain had a very tragical life. Dark, gloomy.”Footnote 15

By the time Ilf and Petrov came to America, the heyday of Soviet satire was passing.Footnote 16 When the reporters from the New Yorker, Harold Ross and A. J. Liebling, wondered whether the Second Five-Year Plan “had anything to say about humor,” Petrov responded, “it hasn’t.” At the same time, Ross and Liebling reported that both authors were “somewhat concerned” by Commissar of Enlightenment Anatoly Lunacharsky’s warning that at some point there would be no “imperfections” left to satirize in the Soviet Union. To the question of what the writers would do then, “Petrov said that there would always remain some material: standard stuff like mothers-in-laws.” But America was a different story. In the United States they could describe “rogues, swindlers, and other raffish characters” to their hearts’ content.Footnote 17

As it turned out, Ilf and Petrov’s American road trip was their last major collaboration. Ilf, whom the New Yorker profile described as “gaunt,” was ill with tuberculosis. He died in April 1937, just as the first edition of Low-Rise America was published. In 1942, Petrov, working as a war correspondent, died in a plane crash. Their untimely deaths helped to shield them and their work from political attacks. Such attacks were certainly possible in the toxic atmosphere of the Stalinist purges, as the authors well understood. Nonetheless, the travelogue remained a popular Soviet guide to all things American and, with a hiatus during the so-called anti-cosmopolitan campaign of the late 1940s, widely available.Footnote 18

Fiction and Fact

In early October 1935, Ilf and Petrov, traveling as reporters for Pravda, arrived in New York City in style but on a budget. They sailed from Le Havre on the Normandie, at the time the largest, fastest, and swankiest ship afloat. Because it was the off season, the cruise line upgraded them from tourist to first-class accommodation. In letters to their wives, Ilf and Petrov described their cabin as “luxurious,” paneled in highly polished wood, with two wide wooden beds, two “huge wall closets with a million hangers” for their meagre wardrobes, armchairs, and a private bath.Footnote 19 Their first night in New York, the authors paid $5 (the equivalent of about $110 in 2023) for an “old-fashioned” room at the Prince George Hotel. Conveniently located on Twenty-Eighth Street between Fifth and Madison Avenues, the hotel attracted many Soviets doing business in the United States. The next day, after meeting with the Soviet consul in New York, they moved to what Petrov described as a “very fashionable area” of Midtown Manhattan near Park Avenue, Radio City, and the Empire State Building. From their room on the twenty-seventh floor of the Shelton Hotel at Lexington and Forty-Ninth Street (three stories below Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1920s studio) they had an “enchanting” view of Manhattan’s “most famous skyscrapers,” Brooklyn, and two bridges over the East River, which Petrov mistook for the Hudson.Footnote 20 It is not clear who picked up the bill. Ilf, who brought $999 to New York, carefully kept track of expenses down to a ten-cent cup of tea. But he did not specify the cost of the room overlooking New York.Footnote 21

The pair’s first big purchase in the United States was a “splendid typewriter” ($33), on which they immediately began documenting their journey.Footnote 22 Like many Soviet writers, Ilf and Petrov had experience as journalists, novelists, playwrights, and screenwriters. The work they produced during and after their trip to the United States attests to this flexibility. They published feuilletons in Pravda while still in the United States and sent numerous letters home. Ilf kept a journal and took hundreds of photographs. In 1936, Ogonek, something like a Soviet Life magazine, serialized their photo essay “American Photographs,” which featured Ilf’s photos and their collaborative text.Footnote 23 Low-Rise America itself defies classification. Literary critics have variously identified it as a book-sketch, literary reportage, a novel, a satire, a picaresque, and a travelogue.Footnote 24

Clearly grounded in fact, Ilf and Petrov’s literary production blurred the border between documentary and fiction. Their published work often hews closely to notes made and letters sent during the trip. My research in American archives and published sources largely corroborates their tales. Nonetheless, Ilf and Petrov took many liberties with chronology, names, and identifications. In addition to obscuring many of their contacts’ roots in the Russian empire, Ilf and Petrov left quite a bit out of their published work – notably Ilf’s uncles and cousins in Hartford and the writers’ efforts to sell a screenplay. Such “refashioning of factual material” was common in Soviet newspaper sketches, which aimed not only or primarily to inform readers but to persuade and activate them.Footnote 25

While Ilf and Petrov’s published work left out and reworked a great deal, it was not straightforward anti-capitalist propaganda. As reporters for Pravda, the writers’ remit was highlighting the “distance” that separated “the world of socialism” from the “the capitalist world.”Footnote 26 But they were always astute observers, attuned to, and willing to include, the perspectives of people who straddled the divide between “ourselves” and the Other. Having received a $300 advance from their American publisher, which bankrolled their brand-new Ford Fordor Sedan ($260 down and $312 due in two months), Ilf and Petrov collected their impressions with the expectation that their travelogue would have audiences in both the Soviet Union and the United States.Footnote 27 Certainly, they included many condescending generalizations about Americans: they are loud and always laughing; they lack curiosity; they prefer trashy movies to good books. Yet Ilf and Petrov also found much to admire and described plenty of Americans who did not fit the stereotypes.Footnote 28 The very forms in which they told their tale – the photo documentary and the picaresque – connected them to modernist literary experiments in both the Soviet Union and the capitalist West that challenged simplistic ways of seeing the world.Footnote 29

On the Road

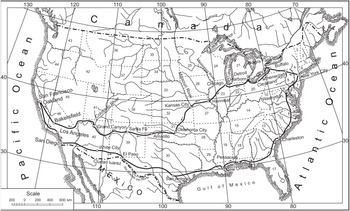

From their first days in New York, Ilf and Petrov started planning an American road trip. Initially, their plans were modest. In early October, Ilf wrote his wife, Maria Nikolaevna, that they would undertake a two-week trip with the Soviet consul to Chicago and Detroit, then to Canada and back to New York City.Footnote 30 Within two weeks, their plans became grander: a “colossal journey” of more than 15,000 kilometers (9,300 miles) to begin in early November. Doing some calculations in his notebook, Ilf figured the two-month journey would set them back about $2,000. Petrov sketched the proposed route for his wife, Valentina Leontevna: “New York, Buffalo, Niagara Falls, across Canada to Detroit, Chicago, Kansas City, Santa Fe, then … to San Francisco. That’s already California. Then – Los Angeles (including Hollywood), San Diego, a bit of Mexican territory, Texas, Mississippi, Florida, Washington, New York.” Upon returning in January 1936, Ilf and Petrov planned to take a twelve- or fourteen-day trip by “banana boat” to Cuba and Jamaica before sailing for home via England. The eight-week road trip largely followed this ambitious itinerary; the pair decided to skip the “tropics,” likely out of growing concern for Ilf’s health (Figure 0.3).Footnote 31

Figure 0.3 The route of Ilf and Petrov’s road trip as mapped in Low-Rise America

While working out their route, Ilf and Petrov traveled around the East Coast, visiting Washington, DC, Hartford, and the General Electric (GE) headquarters in Schenectady, New York. They made the last of these trips on 28 October 1935 with Solomon Trone, a retired engineer who had worked for GE in the Soviet Union, and his wife Florence. In early November, the Trones agreed to guide Ilf and Petrov on their journey through the “real” America of small towns and low-rise buildings.Footnote 32 Florence did the driving. In Low-Rise America, Ilf and Petrov turned the couple into Mr. and Mrs. Adams, retaining his connection to GE and her skill as a chauffeur.

Eighty-four years later, with Ilf and Petrov’s copious notes as my guide, I undertook my own Soviet American road trip. Each stop along their route became a discrete research problem, and each vignette required its own, often creative, sourcing solution. I tracked down a wide range of characters who had interacted with Ilf and Petrov: diplomats, journalists, anthropologists, artists, poets, novelists, filmmakers, engineers, jokers, dockworkers, revolutionaries, and a few scoundrels. In some cases, I was able to corroborate their stories. When I found no direct trace of Ilf and Petrov’s visit, I investigated their contacts’ wider connections to Soviet visitors and Soviet culture. In addition to personal papers, the book makes extensive use of institutional, governmental, and corporate archives to establish the conditions under which personal and cultural exchanges occurred. The most challenging problem was finding the ordinary people with whom Ilf and Petrov interacted. I drew on community oral history projects, including a remarkable series of life history interviews collected in 1935–1936 as part of a survey of San Francisco’s ethnic minorities. In addition to archival sources, I have employed published sources including newspapers, memoirs, and contemporary anthropological research to get a sense of how individuals participated in and understood cultural exchanges.

My road trip through the past begins with a review of the rules of the road and lay of the land: visa regulations, travel restrictions, and must-see attractions. But I focus on the process of travel, the planned and chance encounters that transform an itinerary into a journey. My purpose in excavating the archival traces of Ilf and Petrov’s trip was less to judge their accuracy than to locate their informants’ perspectives. Read against Ilf and Petrov’s notes and narratives, the American stories illuminate the shared concerns as well as the preconceptions and misconceptions that shaped and sometimes limited efforts to understand the Other.

I also retraced Ilf and Petrov’s road trip more literally. Following their abundant clues, I was able to rephotograph many of Ilf’s subjects from virtually the same spots from which he shot them in 1935. Rephotography can be a powerful means of documenting social change. For sociologists, it involves producing photographs of a particular place, social group, or phenomenon over time and reviewing the resulting photographs for evidence of change.Footnote 33 Ilf’s photographs are well suited to this technique as he was explicitly interested in documenting the social reality of the Depression. But I was less concerned with establishing what was/is in front of the lens than what the photographer cropped. Locating Ilf’s vantage point, standing almost literally in his shoes, allowed me to see how he framed his shots and constructed his view of “real America.”

In undertaking my own Soviet American road trip, I tried, like Ilf and Petrov, to travel and observe unhurriedly, striving to see as much as possible. Like the Soviet visitors, I made the trip always aware of the difficulty of leaving my own world behind. For Ilf and Petrov, the American highways over which they traveled were always “in our thoughts” Soviet highways. Similarly, for the historian traveling the highways of the past, the present is never far away. The travelers’ investigations of American modernity, inequality, racism, and immigration inevitably call to mind current problems. Imagining present-day landscapes as the subject of the Soviet author and photographer’s gaze opens unexpected alternatives to our own ingrained ways of seeing Russia, America, and ourselves.Footnote 34