Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) is a common (fourth most prevalent) yet underestimated mental disorder with a lifetime prevalence of 12.1%. Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters1 This excessive fear of being negatively judged, embarrassed or humiliated during social interactions has many consequences such as social isolation and functional impairment and often leads to psychiatric complications such as depression, addiction and suicidal ideation. Reference Ruscio, Brown, Chiu, Sareen, Stein and Kessler2,Reference Wang, Berglund, Olfson, Pincus, Wells and Kessler3 Paradoxically, despite its frequency, severity and the existence of effective treatments, SAD remains largely undertreated. Reference Ruscio, Brown, Chiu, Sareen, Stein and Kessler2,Reference Wang, Berglund, Olfson, Pincus, Wells and Kessler3 Lack of treatment-seeking by people with SAD may be linked to the nature of the disorder itself. Patients with SAD seem to avoid healthcare services like they do other social interactions. Reference Wang, Berglund, Olfson, Pincus, Wells and Kessler3,Reference den Boer4 They feel ashamed of their symptoms and fear discussing them with others, including healthcare professionals. Reference Olfson, Guardino, Struening, Schneier, Hellman and Klein5 Moreover, psychotherapy itself can be perceived as highly frightening or a threat to their need for privacy. Reference Heimberg and Becker6 Patients with SAD often wait many years while their symptoms evolve before consulting, by which time complications have already occurred. Reference Ruscio, Brown, Chiu, Sareen, Stein and Kessler2–Reference den Boer4

There are effective treatments for SAD that rely on medication or psychotherapy. Reference Blanco, Heimberg, Schneier, Fresco, Chen and Turk7–Reference Katzman, Bleau, Blier, Chokka, Kjernisted and Van Ameringen9 The consensus in the field of psychotherapy calls for cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) either in an individual or group format. Reference Katzman, Bleau, Blier, Chokka, Kjernisted and Van Ameringen9,Reference Rodebaugh, Holaway and Heimberg10 Although the group setting presents several advantages (for example group members readily available to conduct exposure, mutual support from group members, vicarious learning) it also has limitations. Reference Stangier, Heidenreich, Peitz, Lauterbach and Clark11 Because of the need to manage a whole group of people, treatment may be less individualised and exposure difficult to handle for the therapist. Therapy in an individual setting can be an alternative to the group format that overcomes those limits. Reference Stangier, Heidenreich, Peitz, Lauterbach and Clark11 However, in vivo exposure exercises (for example asking for the time on the street, browsing in a shop) raise the same issues regarding arousal and loss of privacy as CBT in a group format and may be cumbersome for therapists (for example requiring time to go outside the office for exposure, gathering staff in a room for exposure to public speaking, or planning and assisting patients in embarrassing situations). These drawbacks of standard CBT can be overcome with an alternative medium of exposure: virtual reality (VR) or in virtuo exposure (an expression coined by Tisseau Reference Tisseau12 by analogy to adverbial phrases from Latin such as in vivo and in vitro). Known since the 1990s, CBT with in virtuo exposure is now seeing a renewal of interest because of the current upsurge in virtual technologies and associated possibilities (such as 3D graphics, augmented reality, affordable head-mounted displays developed for video games, smartphone applications and VR using smartphones as head-mounted displays). These technologies have been used extensively with specific phobias (such as fear of flying) but their applications now extend to more complex disorders (for example obsessive–compulsive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder). Reference Bouchard and Wiederhold13 In specific phobias, it remains clinically meaningful to refrain from using CBT strategies other than plain exposure, the clinical cases are usually less complex, and the stimuli used for exposure are less complex and varied than for other anxiety disorders. Compared with phobias, using VR with SAD requires a larger range of scenarios, cues eliciting social fears and virtual environments.

In the case of SAD, CBT with in virtuo exposure could offer several advantages compared with traditional CBT. Reference Bouchard, Bossé, Loranger, Klinger, Wiederhold and Bouchard14 Therapists no longer need participants for social exposure, which can now be undertaken by virtual humans. The use of virtual scenarios allows for controlled, manageable and reproducible social exposure. Therapists also have the possibility of varying the context of immersion (for example shops, restaurants) without ever leaving the office, allowing for complete confidentiality and maximising the generalisation of inhibitory learning. Reference Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek and Vervliet15 In addition, according to patients, in virtuo exposure is considered less frightening than in vivo exposure. Reference Garcia-Palacios, Botella, Hoffman and Fabregat16 In sum, CBT with in virtuo exposure could be a particularly enticing form of therapy for the treatment of SAD to reduce patients' treatment avoidance and facilitate the task of planning out treatment for therapists. Given most previous studies have been encouraging, but have some limitations (considered more fully in the Discussion), Reference Owens and Beidel17–Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24 we propose that a full individual CBT treatment with in virtuo exposure is an effective, efficient and practical alternative to standard individual CBT in the treatment of SAD. Comparisons between individual CBT treatment using either in vivo or in virtuo exposure and a waiting-list control condition were conducted, with the hypothesis that CBT with in virtuo exposure would be more effective and more practical for therapists than CBT with in vivo exposure.

Method

This study was conducted at the Laboratoire de Cyberpsychologie de l'Université du Québec en Outaouais (Gatineau, Québec, Canada). Patients with SAD were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: individual CBT with in virtuo exposure, individual CBTwith in vivo exposure or a waiting list. After 12 weeks on the waiting list, participants in this condition were offered a combined treatment (not reported here). The institutional review board approved the protocol and all patients provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study. The trial was registered with ISRCTN: 99747069.

Selection criteria

Participants were recruited through referrals from practitioners at the investigators' site and advertisements in local newspapers and university networks. Eligible participants were interviewed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams25 (all diagnoses were reviewed and confirmed by a second assessor) and had to meet the following criteria: French-speaking men and women aged 18 to 65 years with a primary DSM-5 diagnosis of SAD 26 for at least the past 2 years (all diagnoses were reviewed and met the criteria for DSM-5). If patients were on any current psychoactive medication and still met the diagnostic criteria of SAD, the medication had to: (a) be stable (same type and dosage) for at least 6 months and (b) remain unchanged throughout the study. Exclusion criteria included patients with dementia, intellectual disability, amnesia, schizophrenia, psychosis or bipolar disorder; SAD being secondary to a DSM-IV diagnosis; and patients receiving any form of concurrent psychotherapy or having a history of seizures. Random assignments were generated with a random numbers table prior to recruitment. Assignments were concealed until the first therapy session began.

Systematic assessment

Regarding clinical outcomes, self-administered assessments were conducted just before and immediately after treatment for each group and at the 6-month follow-up for the two CBT groups only. The primary outcome was identified before the study began as the total score on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-Self Reported version (LSAS-SR), Reference Heeren, Maurage, Rossignol, Vanhaelen, Peschard and Eeckhout27,Reference Mennin, Fresco, Heimberg, Schneier, Davies and Liebowitz28 which assesses fear and avoidance of a range of social interactions and performance situations. Secondary outcomes were the total scores of three social phobia scales: Social Phobia Scale (SPS); Reference Safren, Turk and Heimberg29 Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS); Reference Safren, Turk and Heimberg29 and Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE). Reference Watson and Friend30 Potential associated depressive symptoms were also measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). Reference Beck and Steer31 Moreover, a behavioural assessment task (BAT) was conducted before the first and after the last therapy sessions. Patients had to give an impromptu speech with the instruction for it to last as long as possible (6 min maximum). The speech was video recorded and the patients' behaviour was evaluated using the Social Performance Rating Scale (SPRS) Reference Fydrich, Chambless, Perry, Buergener and Beazley32 by three independent assessors, masked to hypotheses and treatment conditions. As in Kampmann et al's study, a measure of clinically significant change was used and defined as statistically reliable change index on either the LSAS-SR or the FNE. Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24

In order to study the practical and financial resources needed for exposure sessions, the Specific Work for Exposure Applied in Therapy (SWEAT) Reference Robillard, Bouchard, Dumoulin, Guitard, Wiederhold, Riva and Kim33 scale was completed by therapists after each therapy session where exposure was conducted. Items measured topics such as effort in terms of cost, time and planning needed to fine-tune and conduct exposure, and difficulties encountered (for example computer problems). The total score was averaged across the 294 exposure sessions. Treatment credibility Reference Borkovec and Nau34 and working alliance Reference Horvath and Greenberg35 were measured to assess potential differences between conditions and as predictors of treatment outcome. Unwanted negative side-effects induced by immersions in VR (commonly referred to as cybersickness) were measured with the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire (SSQ). Reference Kennedy, Lane, Berbaum and Lilienthal36 According to clinical guidelines suggested by Bouchard et al, Reference Bouchard, Robillard and Renaud37–Reference Bouchard, Robillard, Renaud and Bernier39 the SSQ was administered before and after the immersions in order to control for a priori symptoms that could be confounded with cybersickness, and raw scores are reported. The feeling of presence was also measured post-immersion with the Presence Questionnaire (PQ) Reference Witmer and Singer40 and the Gatineau Presence Questionnaire (GPQ), Reference Laforest, Bouchard, Crétu and Mesly41 a four-item measure rated on a 0 to 100 scale.

Therapy

The individual CBT treatment was adapted from the model and approach of Clark & Wells. Reference Tisseau12,Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier42,Reference Clark, Ehlers, McManus, Hackmann, Fennell and Campbell43 Standardised treatments were conducted for 14 weekly 60 min sessions. Therapists were graduate students experienced in CBT for anxiety disorders and had at least a full year of practical experience in in vivo or in virtuo exposure. Patients were assigned to one of four therapists based on matching schedules and availability. Overall, the distribution of treatment conditions was balanced among the therapists. CBT with in virtuo exposure followed the same methodology as CBT with in vivo exposure, with the only difference that it exclusively used VR immersion to conduct exposure (i.e. no in vivo exposure). Participants in the in virtuo condition were instructed not to engage in any exposure in vivo. No systematic exposure homework assignments were given to participants. In both conditions, exposure exercises were scheduled from the seventh to the fourteenth sessions and lasted about 20–30 min per session. The amount of time dedicated to exposure was set to limit the risk of cybersickness. In accordance with the inhibitory learning model, Reference Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek and Vervliet15 the focus of the exposure was to develop new, non-threatening and adaptive interpretations of feared social situations, negative evaluation, rejection, embarrassment, loss of social status or being perceived as inadequate. Thus, exposure to the same situation was not necessarily repeated frequently and habituation was not required. Other cognitive therapy strategies (delivered in the first six and the last therapy sessions) included: (a) building a therapeutic alliance; (b) developing a personal case conceptualisation model using patients' own thoughts, symptoms and avoidance/safety behaviours; (c) cognitive restructuring of dysfunctional assumptions and beliefs (for example about excessively high standards of performance, the consequences of behaving in certain ways in social situations, or unconditional negative beliefs about oneself); and (d) relapse prevention.

In vivo exposure

Exposure consisted of role-playing and guided exposure either inside or outside the therapist's office (for example asking for the time in a coffee shop, making mistakes in a public place, being video recorded, wearing two socks of a different colour in public, asking strangers on a date, giving an awkward impromptu speech to an audience of staff members, making improper requests in boutiques and stores) with active modelling from the therapist in early sessions. Laboratory staff members were called upon to conduct exposure (for example constituting a mock audience). In vivo exposures did not match in virtuo scenarios in order to adjust exposures to patients' needs within the standardised treatment protocol.

In virtuo exposure

For CBT with in virtuo exposure, patients were immersed using an eMagin z800 head-mounted display and an InterSense Inertia Cube motion tracker. There were eight exposure scenarios using virtual environments from Virtually Better Reference Anderson, Price, Edwards, Obasaju, Schmertz and Zimand21 and Klinger et al: Reference Klinger, Bouchard, Légeron, Roy, Lauer and Chemin23 speaking in front of an audience in a meeting room (two scenarios); having a job interview (two scenarios); introducing oneself and having a talk with supposed relatives in an apartment; acting under the scrutiny of strangers on a coffee shop patio; and facing criticism or insistence in two situations (meeting unfriendly neighbours, refusing to buy goods from a persistent seller at a store). There was also a neutral scenario without virtual characters used during the first immersion to familiarise patients with VR. The choice of scenario was decided by the patient and the therapist at the beginning of each session depending on the patient's needs. Some scenarios were in the participant's native language (French), and some were in English, if relevant to the patient (i.e. a patient who is bilingual or afraid of speaking in English). The patient had to navigate in VR using the head-mounted display and a wireless computer mouse held in their hand while interacting and speaking aloud to the virtual characters who replied using preformatted answers triggered by the therapists. Patients could be sitting down or standing up during the immersions, depending of what was happening in the virtual scenarios.

Therapist intervention adherence and quality

Treatment standardisation was maximised using treatment manuals Reference Roy, Klinger, Légeron, Lauer, Chemin and Nugues44 and treatment fidelity was maximised through weekly supervisions from the principal investigator. Adherence to research protocols was also assessed by independent raters who reviewed videos of therapy sessions based on a grid used in previous CBT studies. Reference Bouchard, Gauthier, Laberge, French, Pelletier and Godbout45

Statistics

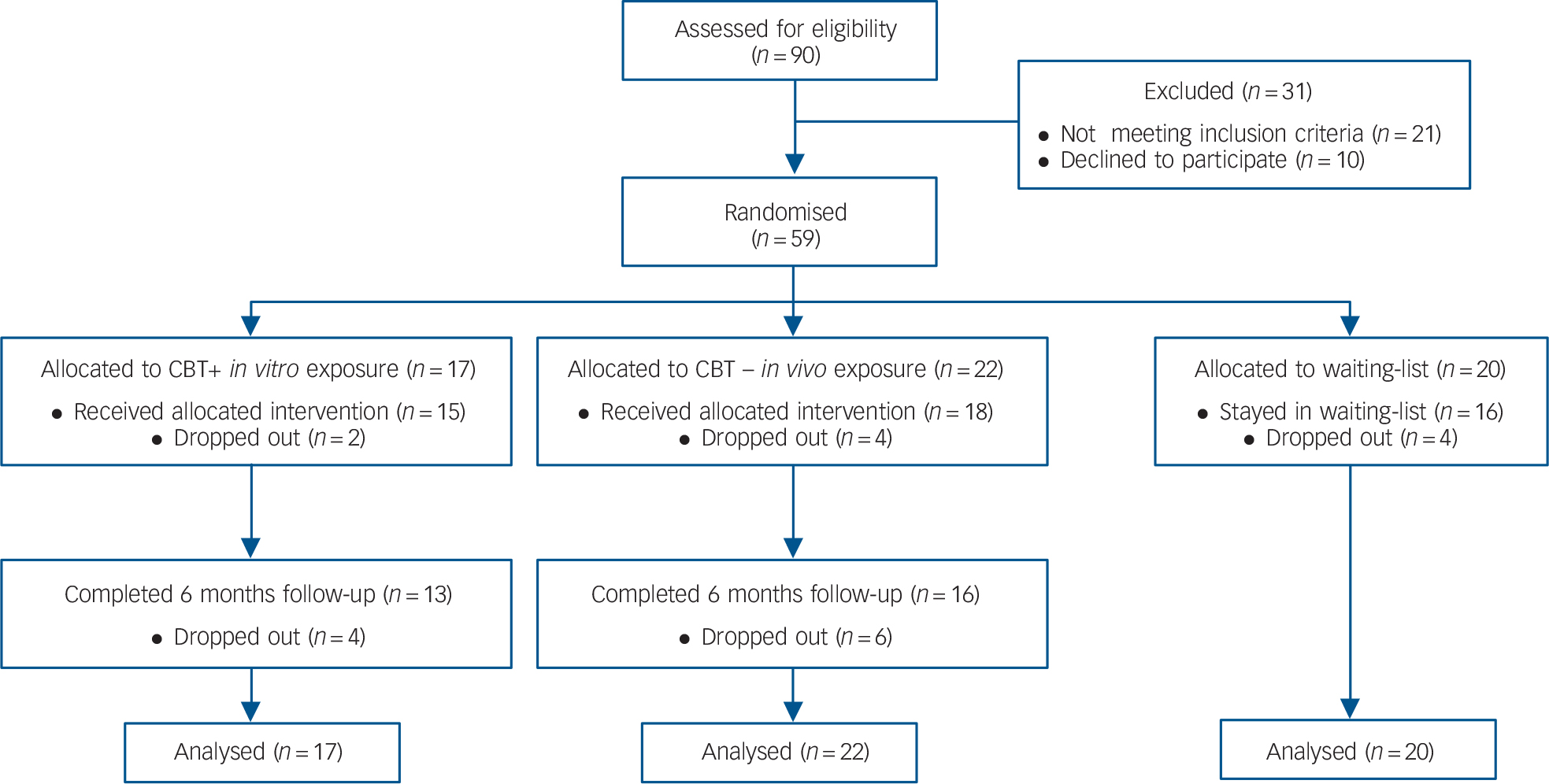

Conditions were compared in pre-treatment using ANOVAs and chi-squared tests. Intent-to-treat analyses based on data from all participants who completed the baseline assessment (Fig. 1) were conducted using the last-observation carried-forward for those who did not complete treatment. Regarding treatment outcome, analyses were performed separately for the pre-/post-treatment comparisons and pre-/post-/follow-up comparisons. Each analysis was conducted using repeated ANOVAs followed by planned orthogonal contrasts. The first analysis compared the two active treatments with the waiting list. The first contrast compared waiting list v. the two CBT conditions, set one-tailed, with the hypothesis that CBT would improve outcomes compared with waiting list. The second contrast compared the two CBT conditions and was set two-tailed. The second analysis compared each CBT format at the three measurement points. The first set or planned orthogonal contrasts compared pre-treatment with follow-up improvements, set one-tailed, with the hypothesis that both outcomes would be improved compared with the baseline. The second set focused on post-treatment to follow-up changes and was set two-tailed. Comparisons for the SWEAT were performed with t-tests, set one-tailed, with the hypothesis that in virtuo exposure would be more practical. Normality of distribution and homoscedasticity were confirmed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Box's M statistics, except for minor deviation from normality on the BDI at post-treatment and follow-up. Significance levels were set at P<0.05 for analyses regarding LSAS-SR and the SWEAT, and family-wise Bonferonni corrected for the secondary measures: BAT, SPS, SIAS, FNE, BDI (P<0.05/5). When planning the study, a power analysis was conducted using effect sizes from previous studies. Reference Stangier, Heidenreich, Peitz, Lauterbach and Clark11,Reference North, North and Coble18,Reference Klinger, Bouchard, Légeron, Roy, Lauer and Chemin23 With an alpha of 0.05 and a power of 0.80, we estimated the effect sizes for the statistical interactions to be very large for the comparisons with the waiting-list condition (i.e. Cohen's f of 0.6, for a total n of 30), and large with the gold-standard condition (i.e. Cohen's f of 0.4, for a total n of 78).

Fig. 1 CONSORT flow diagram of progress through the study.

Results

Recruitment and attrition

The sample size was initially established at 60. Of the 90 individuals that contacted our clinic, 10 refused to participate in the study. The remaining 80 underwent a structured clinical interview (SCID) and 21 people were excluded for not fulfilling the study's criteria. In total, 59 adults were eligible for the study and were randomly assigned to CBT with in virtuo exposure (n = 17), CBT with in vivo exposure (n = 22) or the waiting-list control group (n = 20). There were no differences between conditions regarding sociodemographic or clinical variables (Table 1), including credibility and working alliance. The reasons reported for dropping out were: (a) not wanting to be exposed (n = 1, in vivo); (b) not interested in therapy anymore (n = 2, in vivo); and (c) unknown (remaining participants). There were no statistical differences in the attrition rate between the two groups (Fisher's exact test P = 0.67). For descriptive purposes, Table 2 reports on the feeling of presence experienced and unwanted negative side-effects. Paired t-tests were conducted for each session and none suggested a significant increase in SSQ scores (statistics not reported, all P>0.2).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics for the sample

| Total sample (n = 59) |

CBT+in virtuo

exposure (n = 17) |

CBT+in vivo

exposure (n = 22) |

Waiting list (n = 20) |

Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | F | t | |||||

| Sociodemographic | |||||||

| Female, n (%) | 43 (72.9) | 15 (88.2) | 17 (77.3) | 11 (55.0) | 5.09 | ||

| White, n (%) | 55 (94.8) | 17 (100.0) | 21 (95.5) | 17 (85.0) | 5.88 | ||

| Single, n (%) | 30 (50.8) | 7 (41.2) | 12 (54.5) | 11 (55.0) | 12.15 | ||

| University degree, n (%) | 38 (64.4) | 10 (58.8) | 13 (59.1) | 15 (75.0) | 4.2 | ||

| Low income, n (%) | 16 (21.1) | 4 (23.5) | 5 (22.7) | 7 (35.0) | 2.93 | ||

| Medication, n (%) | 9 (16.7) | 2 (11.8) | 3 (13.6) | 4 (20.0) | 1.58 | ||

| Age, mean (s.d.) | 34.5 (11.9) | 36.2 (14.9) | 36.7 (11.1) | 30.6 (9.1) | 0.2 | ||

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||||||

| Depression | 6 (10.1) | 2 (11.8) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (5.0) | |||

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 6 (10.1) | 1 (5.9) | 5 (22.7) | 0 (0) | |||

| Panic disorder | 5 (8.5) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (10.0) | |||

| Specific phobia | 5 (8.5) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (13.6) | 1 (5.0) | |||

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.0) | |||

| Addiction | 5 (8.5) | 1 (5.9) | 2 (3.4) | 1 (5.0) | |||

| Social anxiety disorder only | 36 (61.0) | 12 (70.6) | 13 (59.0) | 11 (55.0) | |||

| Treatment credibility, mean (s.d.) | |||||||

| Pre-treatment | – | 42.19 (6.4) | 41.7 (6.3) | – | 0.22 | ||

| Post-treatment | – | 43.5 (6.1) | 45.7 (4.7) | – | 1.2 | ||

| Working alliance, mean (s.d.) | |||||||

| After session 2 | – | 220.1 (19.5) | 215.4 (18.8) | – | 0.71 | ||

| After session 7 | – | 219.6 (21.6) | 221.4 (13.8) | – | 0.25 | ||

| Post-treatment | – | 213.9 (58.5) | 223.7 (20.2) | – | 0.66 | ||

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy.

a. Low income <20 000 Canadian dollars.

b. Multiple concurrent comorbidity was common.

Table 2 Unwanted negative side-effects induced by immersions in virtual reality (VR) and the feeling of presence experienced by participants after each exposure session a

| In virtuo exposure session, mean (s.d.) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | |

| Simulator Sickness Questionnaire b | ||||||||

| Before | 3.79 (2.55) | 3.13 (3.2) | 2.13 (2.11) | 1.45 (1.15) | 2.0 (2.17) | 1.92 (2.22) | 1.0 (1.8) | 0.43 (0.79) |

| After | 4.64 (4.81) | 3.27 (3.71) | 1.79 (1.96) | 1.45 (1.15) | 2.73 (2.45) | 1.62 (2.22) | 1.11 (1.17) | 0.57 (0.79) |

| Presence Questionnaire | 78.31 (14.77) | 77.22 (16.95) | 78.71 (20.44) | 82.20 (15.88) | 83.67 (18.37) | 85.23 (18.94) | 82.00 (21.00) | 93.71 (15.22) |

| Gatineau Presence Questionnaire | 51.41 (21.87) | 51.83 (24.55) | 56.17 (25.80) | 64.45 (19.84) | 65.28 (21.78) | 65.73 (23.29) | 57.36 (32.71) | 62.29 (34.77) |

a. Data collected only for patients using VR.

b. Raw scores from the Simulator Sickness Questionnaire, administered before and after each session.

Clinical outcome measures

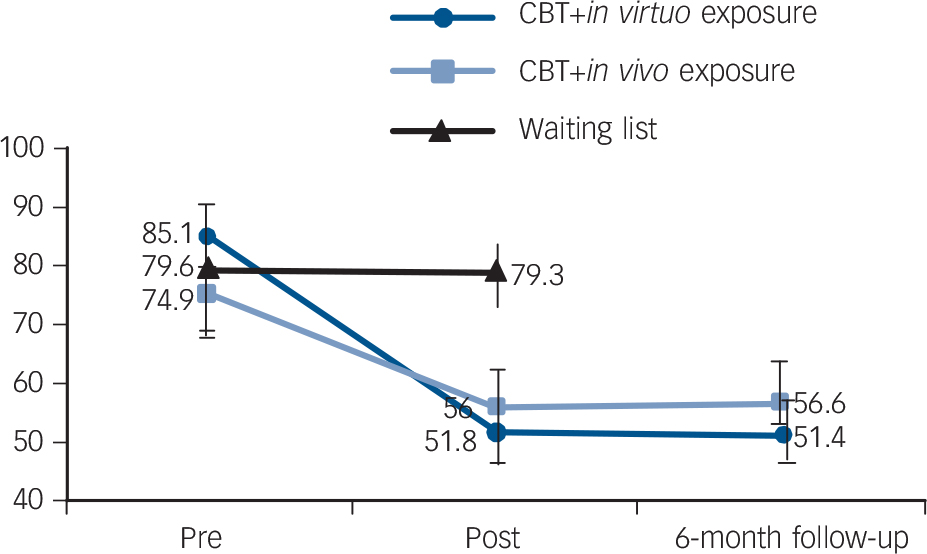

Analyses with the waiting-list condition revealed statistically significant effects of time and time×condition interaction across all outcome measures (Table 3). Planned contrasts revealed significantly decreased scores in the active treatment conditions compared with the waiting list, and no differences between CBT conditions across all outcomes except the LSAS-SR and the SPS, where CBT with in virtuo exposure was more effective than CBT with in vivo exposure. As regards the 6-month follow-up analyses, there was a significant time effect across all outcomes from pre-treatment to follow-up, and no significant change between post-treatment and follow-up (Table 4). The time × conditions interactions and contrasts revealed that CBT with in virtuo exposure was more effective at follow-up on the LSAS-SR only (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 The results on the main outcome measure (Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-SR) comparing cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) with exposure delivered in virtual reality (in virtuo), without virtual reality (in vivo) and a waiting list.

Table 3 Clinical outcomes in post-treatment for participants with social anxiety disorder (SAD) assigned to cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) with in virtuo exposure, CBT with in vivo exposure or waiting-list conditions

| CBT+in virtuo

exposure, mean (s.d.) (n = 17) |

CBT+in vivo

exposure, mean (s.d.) (n = 22) |

Waiting list, mean (s.d.) (n = 20) |

ANOVA | Contrasts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition, F(1,56) |

Time, F(1,56) |

Interaction condition × time, F(2,56) |

Active treatments v. waiting list, t(56) |

CBT+in virtuo

v. CBT+in vivo exposure, t(56) |

||||

| LSAS-SR | 2.16 | 36.82*** | 10.42*** | 4.23*** | 2.02* | |||

| Pre | 85.1 (29.5) | 74.9 (24.5) | 79.6 (24.9) | |||||

| Post | 51.8 (23.3) | 56.0 (26.9) | 79.3 (22.0) | |||||

| BAT | 0.02 | 23.79*** a | 4.16* | 2.78*** a | 0.55 | |||

| Pre | 5.9 (4.1) | 5.4 (4.3) | 6.9 (2.9) | |||||

| Post | 8.4 (4.0) | 8.5 (3.8) | 7.3 (2.6) | |||||

| SPS | 3.2* | 24.09*** a | 15.17*** a | 4.99*** a | 2.69** a | |||

| Pre | 39.0 (16.1) | 30.9 (17.5) | 33.4 (13.9) | |||||

| Post | 19.2 (12.5) | 22.4 (15.7) | 38.9 (14.6) | |||||

| SIAS | 2.98 | 25.37*** a | 9.13*** a | 3.95*** a | 1.90 | |||

| Pre | 49.2 (17.6) | 45.8 (16.9) | 48.6 (13.4) | |||||

| Post | 29.8 (13.9) | 35.4 (17.4) | 49.6 (10.2) | |||||

| FNE | 2.64 | 21.59*** a | 8.12*** a | 3.86*** a | 1.42 | |||

| Pre | 25.6 (5.5) | 23.6 (6.0) | 24.5 (4.8) | |||||

| Post | 18.1 (8.5) | 18.9 (7.2) | 25.2 (4.5) | |||||

| BDI-II | 0.71 | 6.37 a | 6.96** a | 3.72** a | 0.57 | |||

| Pre | 13.5 (9.4) | 14.8 (13.1) | 12.4 (6.9) | |||||

| Post | 6.8 (9.8) | 9.7 (11.1) | 15.5 (11.9) | |||||

LSAS-SR, Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; BAT, Behavior Avoidance Test; SPS, Social Phobia Scale; SIAS, Social Interaction Anxiety Seale; FNE, Fear of Negative Evaluation; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II.

a. Significant when Bonferroni correction applied to the secondary outcome measures.

* P<0.05,

** P<0.01,

*** P<0.001.

Table 4 Clinical outcomes at follow-up for participants with social anxiety disorder (SAD) assigned to cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) with in virtuo exposure or CBT with in vivo exposure

| CBT+in virtuo

exposure, mean (s.d.) (n = 17) |

CBT+in vivo

exposure, mean (s.d.) (n = 22) |

ANOVA | Contracts, pre v. follow-up | Contracts, post v. follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition F(1,37) |

Time, F(2,74) |

Interaction condition, a F(2,74) |

Time, T 1 v. T 3, F(1,37) |

Interaction T 1 v. T 3, F(1,37) |

Time, T 2 v. T 3 | Interaction, T 2 v. T 3 | |||||

| F(1,37) | η2 | F(1,37) | η2 | ||||||||

| LSAS-SR | 0.001 | 43.43*** | 3.54 | 55.03*** | 4.78* | 0.001 | 0.00 | 0.074 | 0.002 | ||

| Pre | 85.1 (29.5) | 74.9 (24.5) | |||||||||

| Post | 51.8 (23.3) | 56.0 (26.9) | |||||||||

| Follow-up | 51.4 (23.3) | 56.6 (29.1) | |||||||||

| SPS | 0.012 | 33.72*** b | 5.05*** | 43.88*** b | 6.37* | 0.61 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.001 | ||

| Pre | 39.0 (16.1) | 30.9 (17.5) | |||||||||

| Post | 19.2 (12.5) | 22.4 (15.7) | |||||||||

| Follow-up | 18.1 (11.6) | 21.6(16.4) | |||||||||

| SIAS | 0.22 | 31.31*** b | 2.23 | 39.03*** b | 2.21 | 1.23 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 0.01 | ||

| Pre | 49.2 (17.6) | 45.8 (16.9) | |||||||||

| Post | 29.8 (13.9) | 35.4 (17.4) | |||||||||

| Follow-up | 29.3 (13.3) | 33.6 (17.4) | |||||||||

| FNE | 0.002 | 23.79*** b | 1.22 | 32.36*** b | 1.15 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Pre | 25.6 (5.5) | 23.6 (6.0) | |||||||||

| Post | 18.1 (8.5) | 18.9 (7.2) | |||||||||

| Follow-up | 17.2 (8.4) | 18.2 (8.4) | |||||||||

| BDI-II | 0.47 | 16.45*** b | 0.24*** | 24.26*** b | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.002 | ||

| Pre | 13.5 (9.4) | 14.8 (13.1) | |||||||||

| Post | 6.8 (9.8) | 9.7 (11.1) | |||||||||

| Follow-up | 7 (9.7) | 9.4 (11.1) | |||||||||

T 1, pre-treatment; T 2, post-treatment; T 3, follow-up; LSAS-SR, Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; BAT, Behaviour Avoidance Test; SPS, Social Phobia Scale; SIAS, Social Interaction Anxiety Scale; FNE, Fear of Negative Evaluation; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II.

a. Interaction condition: (CBT with in virtuo exposure and CBT with in vivo exposure) × time.

b. Significant when Bonferroni correction applied to the secondary outcome measures.

* P<0.05,

*** P<0.001.

Reliable change from pre- to post-treatment was observed in 76.5% (n = 13/17) of participants who had received CBT with in virtuo exposure, 68.3% (n = 15/22) who had received CBT with in vivo exposure, and 30.0% (n = 6/20) in the waiting-list condition (χ2(2) = 9.78, P<0.01). The difference between both active conditions did not approach statistical significance (χ2(1) = 0.33, not significant). How practical and effortless it was for therapists conducting the exposure, as measured with the SWEAT, was rated at 15.24 (s.d. = 3.96) for CBT with in virtuo exposure and 24.46 (s.d. = 9.85) for CBT with in vivo exposure. The Student t-test for unequal variances revealed that using VR was significantly more practical for therapists than traditional exposure (t (22.83) = 3.66, P<0.001).

A multivariate regression analysis was conducted to assess the contribution of treatment modality, treatment credibility and working alliance assessed at session seven on residualised change scores on the LSAS-SR. The regression equation was significant (F (4,27) = 9.22, P<0.001, adjusted R 2 = 0.55), with treatment modality (t = −2.26, P<0.05, semipartial correlation (sr) = −0.29) and working alliance (t = −4.15, P<0.001, sr = −0.54) being the two statistically significant predictors. Conducting the regression separately for each treatment modality revealed that working alliance was a strong and significant predictor of change in LSAS-SR in the CBT with in virtuo exposure condition (t = −2.52, P<0.05, sr = −0.52) and the CBT with in vivo exposure condition (t = −2.8, P<0.05, sr = −0.42), while treatment credibility was not a significant predictor.

Discussion

Main findings

The aim was to document the efficacy of using VR with people with SAD to conduct exposure to a broad spectrum of social situations and report on advantages for therapists in terms of cost and effort of delivering the treatment. The exclusion criteria were kept at a minimum (for example accepting strong comorbidity) to increase generalisability, the manualised treatments did not call for self-exposure homework, the treatment integrity was ensured, and the design included waiting-list and gold-standard treatment conditions with similar treatment except for the delivery of exposure. Results confirmed both hypotheses: conducting CBT with in virtuo exposure was effective and more practical for therapists than CBT with in vivo exposure. All gains were maintained at the 6-month follow-up.

At post-treatment, VR was more effective than traditional exposure on the main outcome measure (LSAS-SR) and one of the five secondary outcome measures (SPS, a global assessment of social anxiety). The latter difference did not reach the corrected significance level at follow-up. VR was neither more nor less effective than traditional exposure on the behavioural measure and on the measures of fear of social interactions, fear of negative evaluation and depressive mood. The success rate in terms of reliable change index was high and similar in both active treatment conditions. These results support what has been found with other anxiety disorders Reference Bouchard and Wiederhold13 and show that CBT combined with exposure in VR is an effective and efficient alternative to classical individual CBT, acutely and in the long term.

Findings from previous studies and comparison with our findings

Previous studies have shown that giving a speech in front of a virtual audience can elicit distress and physiological arousal in patients with SAD. Reference Owens and Beidel17 Numerous studies have also shown the efficacy of in virtuo exposure for treating fear about public speaking. Reference North, North and Coble18–Reference Wallach, Safir and Bar-Zvi20 However, in these studies it was not always clear whether participants' fear of public speaking met the criteria for a SAD diagnosis. In a randomised trial comparing individual CBT with in virtuo exposure to public-speaking situations with group CBT using in vivo exposure for people diagnosed with SAD, Anderson et al Reference Anderson, Price, Edwards, Obasaju, Schmertz and Zimand21 found no differences in treatment outcomes between the two conditions. Patients improved significantly with treatment and improvements were maintained after 1 year. Furthermore, the quality of the working alliance was not different in the two treatment conditions. Reference Ngai, Tully and Anderson22 Even though these results were promising, exposure situations were limited to the fear of public speaking and did not address the broad spectrum of feared social situations and interactions. With DSM-5, 26 specificity was added to describe individuals with the performance-only type of SAD, when fear is restricted to speaking or performing in public. Non-performance social situations often feared in SAD include social interactions (such as having a conversation, meeting unfamiliar people) and being observed (for example eating or drinking in public). 26

Only two previous studies have been published addressing both performance and non-performance social situations in the treatment of SAD with VR. Reference Klinger, Bouchard, Légeron, Roy, Lauer and Chemin23,Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24 Klinger et al Reference Klinger, Bouchard, Légeron, Roy, Lauer and Chemin23 completed a pilot study comparing 12 sessions of group CBT v. individual CBT with in virtuo exposure. The VR exposure scenarios addressed a much broader range of social situations than just speaking in public. Results showed significant improvements in both conditions, with no condition being superior to the other. However, several limitations (lack of control group, exclusion of individuals with severe cases and absence of follow-up assessment) prevent us from drawing firm conclusions. In 2016, Kampmann and colleagues Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24 published a randomised controlled trial comparing CBT with in virtuo exposure to CBT with in vivo exposure for SAD to a waiting list. In order to focus on the effect of exposure, they removed the cognitive components of traditional CBT protocols in both active conditions. Their virtual environments depicted multiple social situations and relied essentially on social interactions and dialogues with virtual humans. Reference Klinger, Bouchard, Légeron, Roy, Lauer and Chemin23 Results revealed that participants in both treatment conditions improved from pre- to post-assessment on social anxiety, avoidance, speech duration during a behavioural assessment task, perceived stress, and avoidant personality disorder related beliefs when compared with the waiting-list control group. Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24 However, CBT with in vivo exposure was found superior to CBT with in virtuo exposure on multiple variables (such as social anxiety, personality disorder related beliefs). In sum, the authors concluded that CBT using only exposure conducted in virtuo can be effective for the treatment of SAD, but stated that VR was less effective than in vivo exposure. Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24 Although these results are interesting, the impact of in virtuo exposure was not as conclusive as in other studies. Limiting exposure to talking to virtual characters and the absence of a cognitive component that facilitates how exposure is mentally processed by patients may explain why in virtuo exposure was less effective than in other published trials. Moreover, Kampmann's team did not evaluate the practical aspects (such as costs, burden for therapists) of using both types of exposure, which is an important factor when considering treatment delivery.

The superiority of in virtuo exposure that we observed on some of the measures has not been found in these previous studies on SAD Reference Anderson, Price, Edwards, Obasaju, Schmertz and Zimand21,Reference Klinger, Bouchard, Légeron, Roy, Lauer and Chemin23,Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24 and the success rates were much higher and consistent with other studies on SAD than those found by Kampmann et al. Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24 Differences in how exposure was conducted might explain this discrepancy. First, results on the SWEAT revealed that conducting exposure was simpler in VR, making it possible to exploit the exposure experiences more. Second, the importance of the therapeutic alliance in predicting outcome highlights the importance of the therapists in conducting exposure. Indeed, in Kampmann et al's study, Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24 patient and therapist were in two separate rooms during exposure exercises with VR. The absence of direct support from the therapist might have had a negative impact on the therapeutic alliance and thus might have reduced the efficacy of in virtuo exposure. Finally, exposure exercises based solely on dialogues with virtual humans raise technical challenges that might make exposure more complicated. Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24

Limitations

Our results should be interpreted within the context of the study's limitations. First, the lack of clinical evaluations by independent assessors masked to the study raises the potential issues of the objectivity of clinical assessments using questionnaires. Behavioural assessments were chosen instead and support results found with self-reports. Second, we studied individual CBT, although the group format is equally effective and widely used. This decision was made for methodological reasons in order to have both treatment conditions differing only in the format of exposure. Individual CBT with in virtuo exposure has been compared with traditional group CBT Reference Anderson, Price, Edwards, Obasaju, Schmertz and Zimand21,Reference Klinger, Bouchard, Légeron, Roy, Lauer and Chemin23 and no differences were found, but their results must be kept in the context of the limitations raised earlier (such as individual v. group format, VR scenarios allowing only exposure to public speaking situations). However, individual exposure with VR may be more enticing to patients disinclined from social exposure or sensitive to strict confidentiality concerning their disorder. Third, replication of this study with a larger sample is still needed, the addition of physiological measures, detailed analyses of presence and maybe the use of d-cycloserine, would allow us to better understand the mechanisms of exposure in VR. Finally, the in vivo exposures did not exactly match the in virtuo scenarios. Therefore, the differences found might be explained by subtle differences in stimuli used and not only the exposure modalities. Emmelkamp and his team Reference Emmelkamp, Krijn, Hulsbosch, De Vries, Schuemie and Van der Mast46 have conducted a study were the virtual scenarios were replicating the stimuli used in the in vivo exposure programme. However, this was a study on the specific phobia of heights, the exposure scenarios were limited to three situations, CBT trials for SAD do not usually replicate exposure tasks (for example Stangier et al Reference Stangier, Heidenreich, Peitz, Lauterbach and Clark11 ), pairing participants on the basis of specific social stimuli would limit how therapists can tailor their interventions to each patient, and our goal was to actually test a broad range of stimuli. Nevertheless, conducting an RCT with all stimuli perfectly matched between conditions would increase the validity of the trial.

Implications

One important contribution of this study is the use of a measure assessing the burden, challenges and costs of conducting exposure. Researchers are encouraged to develop similar measures to replicate our findings. Therapists may be reluctant to use VR, but Bertrand & Bouchard Reference Bertrand and Bouchard47 have shown that the best predictor of intention to use VR is its perceived usefulness. Results on the SWEAT are now providing this information. Because conducting exposure in VR is less cumbersome and rapidly becoming more affordable, there should be an increase in acceptance of this technology. New virtual environments can now depict more complicated social interactions Reference Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek and Vervliet15 and rely on virtual characters with promising artificial intelligence. Reference Kampmann, Emmelkamp, Hartanto, Brinkman, Zijlstra and Morina24 Indeed, researchers should continue refining virtual environments and exposure protocols to further exploit the potential of VR for addressing more complex social interactions and push exposure to allow even more inhibitory learning and disconfirmation of dysfunctional mental representations of social situations.

Funding

The study was conducted with financial support obtained through research grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (grant no. ) and the Canada Research Chairs (grant no. ).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.