The sexual objectification of women’s bodies has been a salient topic for many years in both popular culture and in the academic literature. The #MeToo Movement has shed light on the way in which the objectification and dehumanization of women contribute to sexual assault and harassment. Women political candidates are not spared from this pervasive objectification. For example, when Sarah Palin ran for vice president in 2008, Time magazine called her a “sex symbol” and a nontrivial portion of media coverage was devoted to discussing her appearance and perceived attractiveness (Carlin and Winfrey Reference Carlin and Winfrey2009). More recently, junior congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has become the victim of objectifying rhetoric. Right-wing news and opinion website The Daily Caller published fake revenge porn photographs of the congresswoman. Since women entered the arena of national politics, they have been subject to objectification in a way that men have not.

Objectification is a form of dehumanization, in which an individual’s physical self is the focus rather than “appreciating the other’s mind (intent, thoughts, and feelings)” (Fiske Reference Fiske2009, 32.). To treat people in this way is to deny them of essential human traits and qualities. Psychologists have extensively studied the consequences of sexual objectification. Consumption of objectifying images of women is associated with conformity to masculine gender role norms, the acceptance of rape myths, gender-harassing behavior, and increased acceptance of interpersonal violence (Galdi, Maas, and Cadinu Reference Galdi, Maass and Cadinu2014; Lanis and Covell Reference Lanis and Covell1995). The social psychology literature finds that dehumanization is associated with increased tolerance for violence toward outgroup members as well as other negative intergroup attitudes and behaviors (Ellemers Reference Ellemers2017; Viki, Osgood, and Phillips Reference Viki, Osgood and Phillips2013).

We build upon the literature on objectification and dehumanization to explore whether exposure to objectifying portrayals of women impacts perceptions of women in politics. Using the dual model of dehumanization as a framework, we posit that objectification decreases perceptions of women’s warmth and morality, two essential humanizing characteristics, as well as decreases perceptions of competence and agentic qualities. Via these mechanisms, we expect exposure to objectifying portrayals will decrease voters’ overall positive evaluation and support for women in the political sphere. In particular, we are interested in how the objectification of women as a group and the attitudes that this objectification primes can transfer to the political realm and impact how people perceive women and how much they support the notion of more women in politics. Examining this connection has the potential to help us better understand the seemingly nonpolitical factors that influence our political dispositions, biases, and decision-making. With a historically high number of women running for public office (Dittmar Reference Dittmar2019), it is essential that we fully understand the effect of pervasive objectification on how individuals evaluate and perceive women candidates.

Using original experimental data, we present individuals with either neutral or women-objectifying imagery. We then measure attitudes about the dearth of women in political office, the competence of women politicians, and likelihood of voting for a woman for president. We also gauge support for well-known women politicians and the overall dehumanization of women as a group. We find no evidence that exposure to objectifying portrayals of women has an impact on support for women in politics, evaluations of women politicians, or the dehumanization of women. These results suggest that objectification, particularly when women in politics are not the direct target of the objectification, may not impact overall support for women in politics.

Objectification Theory

Sexual objectification occurs when people’s bodies or body parts are separated from their identity in some way (Bartky Reference Bartky1990). In other words, an individual becomes merely instrumental and stripped of their personhood when objectified. Objectification has been explored by many feminist theorists writing from a social constructivist framework (Bartky Reference Bartky1990; Young Reference Young1980). As Fredrickson and Roberts explain, “The common thread running through all forms of sexual objectification is the experience of being treated as a body (or collection of body parts) valued predominantly for its use to (or consumption by) others” (1997, pg. 174).

The defining feature of objectification is the degradation of another’s agency and autonomy. Often, objectifying images show women’s bodies or body parts as interchangeable with objects or disembodied (Bernard et al. Reference Bernard, Gervais, Allen, Campomizzi and Klein2012). Ultimately, psychologists proposed Objectification Theory to use as a framework for understanding the correlates associated with living in a culture that sexually objectifies the female body (Fredrickson and Roberts Reference Fredrickson and Roberts1997).Footnote 1 Objectification Theory focuses on the risks that objectification poses to women living in this culture. However, later work explored how objectification impacts the attitudes and behaviors of all people. As outlined in the introduction, exposure to objectifying portrayals of women can have negative consequences, such as the acceptance of interpersonal violence and harassment (Aubrey, Hopper, and Mbure Reference Aubrey, Hopper and Mbure2011; Galdi et al. Reference Galdi, Maass and Cadinu2014), rape myth acceptance (Lanis and Covell Reference Lanis and Covell1995), subscription to masculine gender norms (Galdi et al. Reference Galdi, Maass and Cadinu2014), and self-objectification (Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Kallen, Twenge and Fredrickson2006). Wright and Tokunaga (Reference Wright and Tokunaga2016) find evidence that exposure to objectifying depictions of women is associated with attitudes supportive of violence against women.

Images of objectified people, particularly women, pervade pop culture, media, advertisements, and pornography. Social media platforms have continued to increase the proliferation of women as objects (Feltman and Szymanski Reference Feltman and Szymanski2018). Women are displayed as sex objects in 50 percent of advertisements from 58 popular US magazines (Stankiewicz and Rosselli Reference Stankiewicz and Rosselli2008), and this increases to 70.9% when the focus is narrowed to men’s magazines only (Krassas, Blauwkamp, and Wesselink Reference Krassas, Blauwkamp and Wesselink2001).

Dehumanization

Dehumanization and the concept of “humanness” have received a considerable amount of attention from social psychologists.Footnote 2 The notion of dehumanization has most often been studied in relation to ethnicity and race. More specifically, scholars studied phenomena like immigration and genocide and how within intergroup conflict, some groups dehumanize other groups (Chalk and Jonassohn Reference Chalk and Jonassohn1990). Other work within the dehumanization literature has focused on the dehumanization of people with disabilities (O’Brien Reference O’Brien1999), in the medical field (Barnard Reference Barnard and Locsin2001), in technology (Montague and Matson Reference Montague and Matson1983), and on the dehumanization of women in pornography (MacKinnon Reference MacKinnon1987). Broadly, this literature explores the role that perceived humanity plays in intergroup relations and social cognition.

Haslam (Reference Haslam2006) proposed an integrative model of dehumanization that conceives of dehumanization as something that not only occurs in the context of violence and conflict but can also occur in an interpersonal, everyday encounters. This model builds from the research on “infra-humanization” (Leyens et al. Reference Leyens, Rodriguez, Rodriguez-Torres, Gaunt, Paladino, Vaes and Demoulin2001, Reference Leyens, Cortes, Demoulin, Dovidio, Fiske, Gaunt, Paladino, Rodriguez-Perez, Rodriguez-Torres and Vaes2003), demonstrating that people more frequently attribute “secondary” emotions to in-group members rather than out-group members. These secondary emotions can be thought of as essential to the “human essence.” More specifically, Haslam (Reference Haslam2006) purports that dehumanization falls into two categories: animalistic dehumanization, which is the denial of attributes that are unique to humans (e.g. cognitive capacity, civility, moral sensibility and rationality), and mechanistic dehumanization, which is the denial of human nature (e.g. emotionality, interpersonal warmth, and openness). This trait-based approach is a more subtle approach to dehumanization than past conceptualizations, and subsequent research has supported the idea that certain traits are perceived to be “essential” to humans (Haslam et al. Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2008). Those who are denied human uniqueness are stereotyped as lacking the civility and moral sensibility that distinguishes human from animals. Those who are denied human nature are seen as indistinguishable from inanimate objects or automatons. These two forms of dehumanization can operate in interpersonal and intergroup contexts either separately or at the same time (Haslam Reference Haslam2006).

Dehumanization tends to decrease empathy and willingness to help members of outgroups and can even be a precursor to violence (Andrighetto et al. Reference Andrighetto, Baldissarri, Lattanzio, Loughnan and Volpato2014; Viki et al. Reference Viki, Osgood and Phillips2013). Objectification is one way in which dehumanization can manifest and result in negative consequences. For example, Bernard et al. (Reference Bernard, Gervais, Allen, Campomizzi and Klein2012) find that the cognitive process by which people recognize sexualized women is more closely related to analytical processing, a type of processing typically involved in object recognition rather than human recognition. Furthermore, another study identified that male participants more quickly associated sexualized women with first-person action verbs (“handle”) and clothed women with third-person action verbs (“handles”), suggesting that objectification decreases attributions of agency when a target is being objectified (Cikara, Eberhardt, and Fiske Reference Cikara, Eberhardt and Fiske2011).

Objectification and dehumanization in the political sphere

Psychologists have outlined the consequences of living in a culture in which the objectification of women is pervasive, but there is less work on politically relevant outcomes. Heflick and Goldenberg (Reference Heflick and Goldenberg2009) conducted a study in which participants were prompted to consider the appearance of then vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin. They found that focusing on Palin’s appearance reduced perceptions of her competence and humanness. Furthermore, those in the appearance-focused condition were less likely to express intentions to vote for the McCain/Palin ticket than those in the control condition, even when accounting for partisan identification. Objectifying commentary on social media also can impact the evaluation of women candidates, such that objectified women are rated as less credible and less suitable for office (Funk and Coker Reference Funk and Coker2016). To our knowledge, these are the only empirical studies linking objectification to perceptions of political candidates.

There is more recent research uncovering the connections between partisanship and dehumanization. Cassese (Reference Cassese2019, Reference Cassese2020) finds evidence that voters dehumanize opposition party candidates and party members in both blatant and subtle ways, with blatant dehumanization associated with perceptions of greater moral distance between parties. Dehumanization also can impact attitudes toward immigrants (Utych Reference Utych2018) and support for the NFL national anthem protests over police violence (Utych Reference Utych2022). This study makes several contributions to this literature. First, we integrate both the research on Objectification Theory and dehumanization to use both theories as a framework for understanding the mechanisms by which objectification may impact evaluations of women political candidates. The inclusion of the dual model of dehumanization allows us to distinguish between denial of human nature or mechanistic dehumanization and denial of human uniqueness or animalistic dehumanization.Footnote 3 The dual framework, used in recent work (see Cassese Reference Cassese2019), also taps into less blatant forms of dehumanization that occur in everyday life. Secondly, previous literature has focused on how objectification impacts evaluations of a specific candidate (Sarah Palin) or a fictionalized candidate. We examine how objectification could influence perceptions of actual women politicians as well as attitudes about women in politics generally. By assessing perceptions of real, relatively high-profile politicians, we believe this offers a more externally valid and more difficult test of our hypotheses. Thirdly, we seek to understand how the objectification of women can have downstream consequences for all women, even when they are not the direct target of the objectification. Previous work has looked at how objectification of a specific candidate, real or fictionalized, impacts evaluations. Our proposed design explores how objectification of women, in this case via objectifying imagery, can influence attitudes toward women in politics even if they are not the target of the objectification. We purport that objectification can prime dehumanizing beliefs about women as a group and that the objectification present in society seeps over into attitudes toward women in politics.

Using the framework of Haslam’s dual model of dehumanization, we posit that exposure to objectifying portrayals of women will impact how people evaluate women in politics. Objectification, as outlined by feminist theorists such as Nussbaum (Reference Nussbaum1995), involves the denial of autonomy, agency, individuality, and depth that is characteristic of dehumanization. Extant research provides evidence that objectifying portrayals of women decrease perceptions of morality and warmth, a form of mechanistic dehumanization (Haslam et al. Reference Haslam, Loughnan, Kashima and Bain2008; Heflick and Goldenberg Reference Heflick and Goldenberg2009; Heflick et al. Reference Heflick, Goldenberg, Cooper and Puvia2011). Furthermore, objectification decreases perceptions of competence and other agentic qualities, a form of animalistic dehumanization (Heflick et al. Reference Heflick, Goldenberg, Cooper and Puvia2011). For example, women are perceived as less competent when the focus is on their appearance (Heflick and Goldenberg Reference Heflick and Goldenberg2009) as well as when they are dressed provocatively (Loughnan, Haslam and Kashima Reference Loughnan, Haslam and Kashima2009; Vaes, Paladino and Puvia Reference Vaes, Paladino and Puvia2011).

We propose to test the following hypotheses:

H 1: Exposure to objectifying portrayals of women will decrease support for women in politics.

Based on previous research that has found men are more likely to objectify women (Cikara, Eberhardt and Fiske Reference Cikara, Eberhardt and Fiske2011), we also seek to test the hypothesis that exposure to objectifying portrayals of women will increase the dehumanization of women among men but not women. This is consistent with Objectification Theory and the notion that men and women have different reactions to objectification. Women tend to internalize objectifying portrayals and rhetoric, whereas men do not (Gapinski, Brownell, and LaFrance Reference Gapinski, Brownell and LaFrance2003; Quinn et al. Reference Quinn, Kallen, Twenge and Fredrickson2006).

H 2: Exposure to objectifying portrayals of women will decrease support for women in politics among men but not women.

We also seek to test whether exposure to objectification impacts evaluations of actual women who are either in political office or seeking political office.

H 3: Exposure to objectifying portrayals of women will decrease positive evaluations of women politicians.

Again, we might expect heterogenous treatment effects by gender:

H 4: Exposure to objectifying portrayals of women will decrease positive evaluations of women politicians among men but not women.

Finally, we will test whether exposure to the objectifying treatment impacts dehumanization.

H 5: Exposure to objectifying portrayals of women will increase dehumanization of women as a group.

We again expect potential heterogenous treatment effects by gender:

H 6: Exposure to objectifying portrayals of women will increase dehumanization of women as a group among men more than women.

Despite the progress that women have made in the political sphere, particularly within the last few years (Dittmar Reference Dittmar2019), gender-based prejudice and stereotypes that impact voter evaluations of women candidates persist (Ditonto, Hamilton, and Redlawsk Reference Ditonto, Hamilton and Redlawsk2014; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2014). Even in an era of party polarization where these effects can be small to nonexistent (Kalla and Broockman Reference Kalla and Broockman2018), subtle cues can still impact how voters evaluate candidates and politicians.

Experimental design

Sample

Participants were recruited among adults in the USA using the survey recruitment platform, Forthright by Bovitz Inc. on February 11 through February 14, 2022. Participants were invited to participate in a survey about advertisements, personality, and political candidates, and they were compensated $1.50 plus one loyalty credit through Forthright (valued at $0.67).Footnote 4 The age of participants in our subject pool ranged from 18 to 95 with a mean of 46.6. In terms of gender identity, 49.8% of our sample identified as men and 48.8% identified as women. A large majority of our sample identified as White (76.1%), and 33.9% of our sample had at least a bachelor’s degree or higher. Our sample skewed somewhat liberal and Democratic, with 43.8% of participants identifying as Democrats and 22.9% identifying as Republicans. In terms of ideology, 43.6% identified as liberal, 26.4% as moderate, and 30% as conservative. After removing participants who either did not complete the experimental portion (n = 1) or opted to have their data removed (n = 134), we were left with 1,017 respondents.

Upon consenting to participate in the study, participants first completed a set of demographic questions. We measured age, gender, race, education, evangelical identification, ideology, and partisan identification. Given our hypotheses about the potential heterogenous treatment effects across gender, we included a measure beyond binary male/female to include a self-placement on two dimensions – masculinity and femininityFootnote 5 (Bittner and Goodyear-Grant Reference Bittner and Goodyear-Grant2017; McDermott, Tingley and Hatemi Reference McDermott, Tingley and Hatemi2014; Wangnerud, Solevid, and Djerf-Pierre Reference Wangnerud, Solevid and Djerf-Pierre2018). Following Wangnerud et al. (Reference Wangnerud, Solevid and Djerf-Pierre2018), we included a categorical measure of gender identity as well as sex assigned at birth. We included items about media consumption, adapted from Wright and Tokunaga (Reference Wright and Tokunaga2016), to gauge participant self-reported exposure to objectifying content.

Participants were randomly assigned to the objectification treatment condition (n = 514) or the control condition (n = 503). In both conditions, participants viewed a series of eight images for 5 seconds each. A portion of these photos were taken from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS), a large and widely used collection of images that are pretested for arousal and valence (Bradley and Lang Reference Bradley, Lang, Coan and Allen2007). For the objectification condition, we chose four erotica images featuring women’s bodies from the database to use as stimuli photos as well as four photos from actual advertisements that were pretested in a previous MTurk study in March 2018.Footnote 6 For all of the stimuli photos, we applied the Sex Object Test (Heldman Reference Heldman2012) to ensure the presence of sexual objectification. Similar erotica images from the IAPS have been used in other studies (see Friesen, Smith, and Hibbing Reference Friesen, Smith and Hibbing2017). In the control condition, participants viewed a series of eight photos drawn from the IAPS that featured household objects like furniture. After viewing the images, participants were offered an open-ended question asking what items were being advertised in the previous photos. We included this new addition from our pre-analysis plan to further the deception that the study was about advertising, making it less obvious the image viewing was leading directly into questions about women.

In previous studies, researchers have opted to have participants directly objectify or be exposed to the objectification of a specific person. For example, Funk and Coker (Reference Funk and Coker2016) presented participants with a political candidate and in the treatment group, they were instructed to read a Facebook feed that included objectifying comments about the politician. Because we are interested in how the dehumanization and objectification of women generally impact all women, even when they are not the direct target, we seek to prime the dehumanization and objectification of women and demonstrate how these phenomena can transfer to perceptions of women as a group, including women in politics.

Posttreatment, participants were asked to gauge support for women in politics generally. They were asked how much they agree or disagree, on a five-point scale, with the following statements- “There are too few women in high political office in the country today.”, “More women in political office would be a benefit to this country.”, “Women are just not as competent in political office as men are.”, and “I would vote for a woman for the presidency.” The first two statements are modified from a 2018 “Women in Leadership” Pew survey. A mean composite score was generated by averaging responses across the items. After answering these questions, participants evaluated several different women politicians, including Elizabeth Warren, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Nancy Pelosi, Nikki Haley, and Kamala Harris. We chose these politicians because they either recently ran for national office (Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris) or are very well known on a national level according to various polls. Respondents saw a photo of each woman with their name underneath and were asked how positively they would evaluate each political leader. Response categories ranged from 0 to 10 or from “Very Negatively” to “Very Positively.” A mean composite score was generated by averaging responses across the items.Footnote 7 Finally, participants completed a modified version of the dual model of dehumanization scale (Haslam Reference Haslam2006; Haslam et al. Reference Haslam, Bain, Douge, Lee and Bastian2005), evaluating women, as a group, on 10 mechanistic traits and 10 animalistic traits. Response categories were on a four-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely well.” A mean composite was created for the overall dehumanization scale, as well as the mechanistic and animalistic subscales.

Analysis

For the analyses, we follow our pre-analysis plan, registered with Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/4sdwf/. In all our models, we controlled for participant gender, age, race, education, partisanship, and media consumption.Footnote 8 We expected exposure to the objectifying treatment to decrease support for women in politics, decrease evaluations of women politicians, and increase the overall dehumanization of women. We also hypothesized that the relationship between the treatment and the outcomes of interest would be conditional on participant gender. To test the first set of analyses, we regressed mean composite scales for support for women in politics, evaluations of women politicians, and dehumanization on a treatment indicator variable with our control group serving as the reference and including our covariates. In the second set of analyses, we interacted our treatment indicator with our binary gender variable.

Figure 1 demonstrates how the objectifying treatment influences attitudes on women in politics and the overall dehumanization of women as a group. We see no statistical difference between the objectification and control groups on any of the three dependent variables. Contrary to our expectations, individuals in the treatment group did not differ from the control group in their support for women in politics, their evaluation of women politicians, or their overall dehumanization of women as a group. With respect to the covariates, women showed more support for women in politics and higher evaluations of women politicians than men. Higher education and media consumption levels were also significant and positive predictors of support for women in politics and evaluations of women politicians. Identifying as a Republican was negatively related to support for women in politics and evaluations of politicians, and identifying as White was negatively related to evaluations of women politicians.Footnote 9 Full regression results can be found in the Appendix.

Figure 1 Effect of Dehumanization.

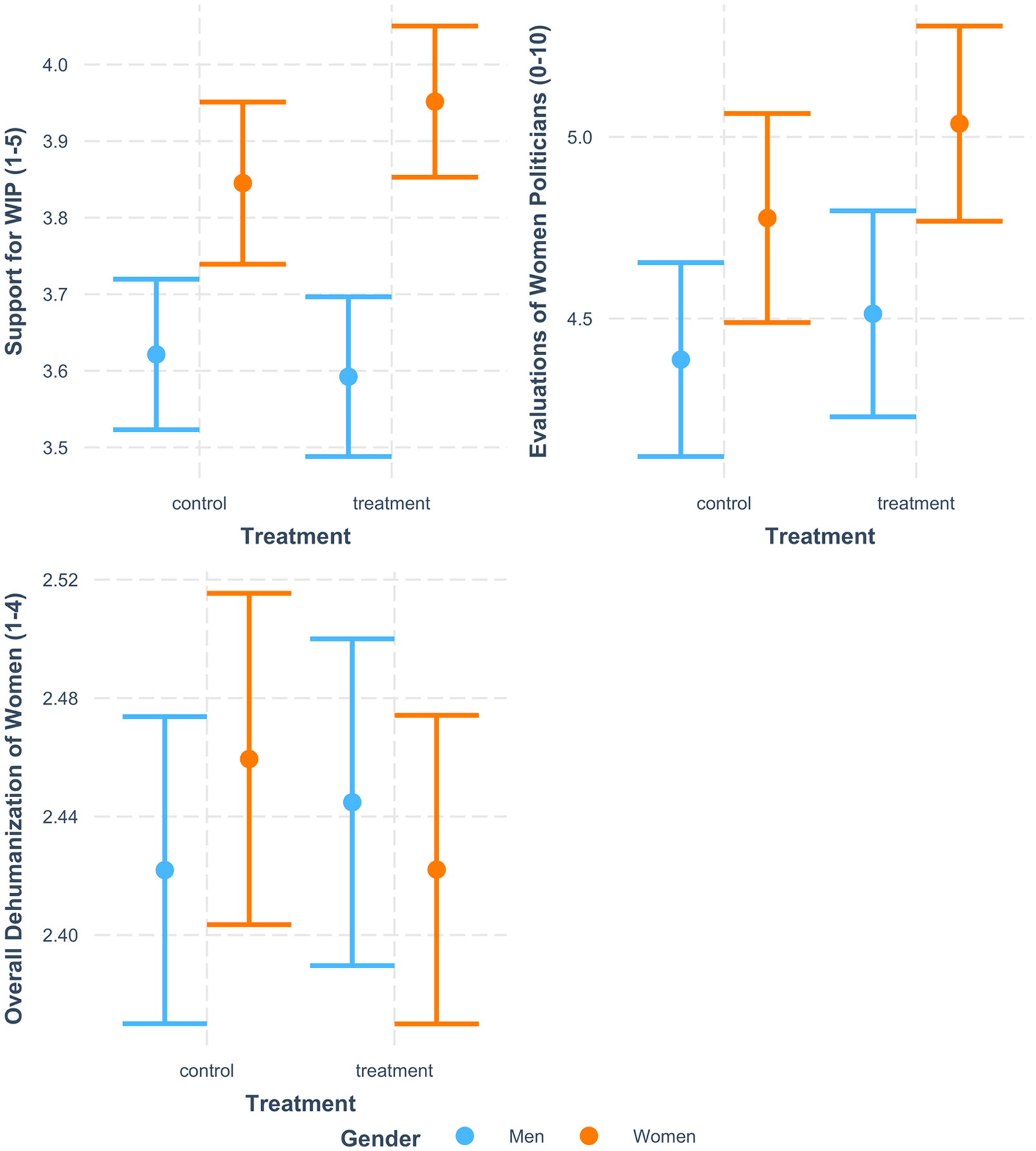

Turning to our second set of analyses in which we predicted that the effect of the treatment would be conditional on participants’ gender, we expected exposure to the objectifying treatment to decrease support for women in politics, decrease positive evaluations of women politicians, and increase the dehumanization of women, among men but not women. To test this second set of hypotheses, we regressed the same three scales on the treatment indicator interacted with our binary gender variable, with the control group and men serving as the reference groups. Figure 2 shows the results. We see no statistical difference between the objectification and control groups on any of the three dependent variables for men or women. Interestingly, although the interaction between gender and the treatment did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance, there does seem to be a gap between women in the treatment group and women in the control when it comes to the support for women in politics measure. Women in the treatment group were slightly more supportive than women in the control group, suggesting that perhaps there was some backlash to the objectifying treatment, though again, the difference did not reach statistical significance, and our measures cannot speak to a backlash mechanism.

Figure 2 Effect of Dehumanization by Gender.

Discussion and conclusion

American women have made great strides in educational attainment, diversifying occupations, and increasing numbers in halls of power. But this progress is countered by a constant onslaught of objectification and dehumanization across social media, mainstream media, product advertisements, and entertainment mediums. Previous research demonstrates women can be reduced to less than the sum of their parts, and this can have consequences for viewing women as agentic, competent humans. We sought to understand whether exposure to everyday objectifying media would bleed into evaluations of women as a group and specifically, women politicians. The good news is at least from this initial study, participants are able to separate objectified women images from how they think of women as agents. Perhaps our participants understood the task and reacted accordingly, but there was still variance in the candidate evaluations and other leadership scales to suggest a minor experimental treatment was not moving the needle in this case. Given the findings about specific politicians like Sarah Palin (Heflick and Goldenberg Reference Heflick and Goldenberg2009), our study suggests that political candidates may need to be the target of objectification and dehumanization for there to be negative effects. Another possible treatment would be to prime an objectifying/control image immediately before each evaluation question rather than show a series of images in a block preceding the question series.

In the end, like many studies based in the US context, partisanship eclipsed other factors in shaping candidate evaluations. Democrats rated their politicians (Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, etc.) more favorably and reported more support for women in leadership, as compared to Republicans. It would be helpful to replicate this study in a less polarized setting or multi-party system to determine whether objectifying exposure could shift attitudes in the absence of strong partisan identities. Although our null results suggest that the indirect objectification of women may not permeate the political sphere, other work finds that women’s objectification of their own bodies, known as self-objectification, is associated with decreased political engagement (Gothreau Reference Gothreau2021; Calogero et al. Reference Calogero, Tylka, Donnelly, McGetrick and Leger2017). More research should be done to advance our understanding of the way in which pervasive objectification may or may not relate to politics.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2022.15

Data availability

Support for this research was provided by Western University Samuel Clark Research Grant. The data, code, and any additional materials required to replicate all analyses in this article are available at the Journal of Experimental Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BZAW8R

Acknowledgements

We thank the Faculty of Social Science at Western University for the generous funding of this research. We also thank Bert Bakker for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this pre-registered report.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.