Introduction

Research suggests that Hurricane Maria caused well over 1,000 deaths in Puerto Rico and that the U.S. federal government’s neglect was a contributing factor (Rivera and Rolke Reference Rivera and Rolke2018; Sales and Hansen Reference Sales and Hansen2020; Santos-Lozada and Howard Reference Santos-Lozada and Howard2018). The different response in Texas only months earlier suggests that the U.S. government—and the citizens it represents—may value individuals on the mainland more than they do those in the U.S. government’s overseas territories. Yet Puerto Ricans, just like Texans, are legal American citizens, so why does substantive inequality appear to remain so stubbornly persistent? Historical work on this topic points to the role that race and language play in Americans’ willingness to accept colonial territories as equal members of the union (see, e.g., Immerwahr Reference Immerwahr2019)Footnote 1 and thus deserving of an equitable distribution of resources. In this paper, I analyze how a theoretically race-neutral policy, disaster relief, becomes racialized and, in turn, affects substantive equality for ethnoracialFootnote 2 minorities.

I focus specifically on the formation of public opinion on the recovery stage of hurricane relief—the one-year period following a disaster that is characterized by repairing, rebuilding, and allocating resources (Fothergill, Maestas, and Darlington Reference Fothergill, Enrique and Darlington1999)—in Puerto Rico. I designed and administered an original experiment embedded in the nationally representative 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) to tease out the marginal and intersectional effects of hurricane victims’ skin tone and language on Americans’ preferences over hurricane relief and substantive equality for Puerto Ricans. Hurricane victims in Puerto Rico act as the source of information in this experiment. Respondents to the CCES are randomly assigned to watch one of four 30-second videos that explain the needs of disaster victims in Puerto Rico. The content of the four videos is exactly the same; the treatments are the skin tone and spoken language of the person delivering the message. By varying the actors’ skin tone (light or dark) and language (Spanish or English) in the videos, I am able to assess the ways in which these ethnoracial markers shape Americans’ preferences about a putatively race-neutral policy (disaster relief).

Dissecting public opinion on this issue offers three important contributions to the existing scholarship on Americans’ attitudes toward minorities as well as broader theories on (current or former) colonial countries’ policies toward individuals of their territories. First, this paper is one of the first to explore attitudes toward Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans living on the island. Despite having been American citizens for over 100 years, the 3.5 million Puerto Ricans who live on the island have less political influence over the island’s fate than those who live on the U.S. mainland (about 5 million). The former cannot vote in national elections,Footnote 3 do not have a voting member of Congress, and do not have access to certain economic support or protections provided to U.S. states. Due to the ongoing financial crisis and the damage caused by Hurricane Maria in 2017, the case of Puerto Rico has figured prominently in American media coverage as of late, but we know little about how the attitudes that shape U.S. policy toward Puerto Rico are formed. In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, many politicians and commentators have suggested that the inadequate response by the federal government to the disaster is a function of race, language, and Puerto Rico’s ambiguous status as belonging to, but not being part of, the American political community.Footnote 4 Do perceptions about the language and skin tone of Puerto Ricans indeed influence Americans’ support for disaster relief spending, as well as substantive political equality for Puerto Ricans?

Second, scholars have increasingly recognized that processes of ethnoracialization are multidimensional, a “bundle of sticks,” so to speak (Sen and Wasow Reference Sen and Wasow2016). Embracing the framework developed by Kim (Reference Kim1999; Reference Kim2000; see also Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017), this paper focuses on two particularly important dimensions: inferiority–superiority, operationalized by skin color, and foreignness–Americanness, operationalized by language (either English or Spanish). On the one hand, Puerto Ricans—having long been American citizens—are the archetypal group (along with Black Americans) that is thought to suffer from the cultural pathologies of an American, racial underclass (Lewis Reference Lewis1966). On the other hand, Americans have also perceived Puerto Ricans as a foreign or quasi-foreign, migrant group due to their linguistic and cultural differences, as well as the island’s territorial and political separation from the U.S. polity. Studies have traditionally explored the marginal role of one dimension or the other as potential bases of ethnoracial subordination. In this experiment, I parse not only the marginal effects of skin color and language but also the ways in which these two dimensions intersect in counterintuitive ways. Given the changing demographics of the United States (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2004), determining the ways in which both of these cross-cutting cleavages contribute to processes of ethnoracialization is essential.

Third, unlike policies related to, for example, affirmative action, reparations for slavery, or the racial integration of public schools, this paper focuses on a political issue that is not inherently racialized. Nevertheless, a policy need not be explicitly about race for that policy to become racially charged, as is evident from American public discourse about welfare spending, taxation, and police violence (Gilens Reference Gilens1995; Sears et al. Reference Sears, van Laar, Carrillo and Kosterman1997; Valentino Reference Valentino1999; Valentino, Hutchings, and White Reference Valentino, Hutchings and White2002), among others. At least since Hurricane Katrina (2005), disaster relief has also become a racialized policy issue (Iyengar and Morin Reference Iyengar and Morin2006; Johnson Reference Johnson2011) and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. This paper’s focus on the effects of racial and linguistic cues helps explain the process by which policies that are not inherently racialized nonetheless often become so. Given that ethnoracial minorities are likely to be disproportionately affected by climate change (Bolin and Kurtz Reference Bolin, Kurtz, Rodríguez, Donner and Trainor2018; Davidson et al. Reference Davidson, Price, McCauley and Ruggiero2013; Fothergill, Maestas, and Darlington Reference Fothergill, Enrique and Darlington1999), understanding how a theoretically race-neutral policy like disaster relief becomes ethnoracialized is likely to only grow in importance.

My findings suggest that the Spanish language has a negative marginal effect on Americans’ attitudes toward hurricane relief and substantive political equality for Puerto Ricans.Footnote 5 There is scant evidence for a marginal effect of the skin color treatment. The greatest insight emerges from analysis of heterogeneous effects by respondents’ party, race, and perceptions of Puerto Ricans’ Americanness. I show that the dark skin treatment causes less support for Puerto Rico among respondents who view Puerto Ricans as more American and among respondents more likely to harbor stereotypes about the cultural pathologies of an American underclass. In particular, the interaction effect, by party (Republicans versus non-Republicans) and race (white versus nonwhite), of the dark- versus light-skin treatment on support for Puerto Rico is negative. The same result obtains for the interaction effect by perceptions of Puerto Ricans’ Americanness (knowledge of Puerto Ricans’ American citizenship and whether Puerto Ricans speak mainly English or Spanish).

In contrast, the Spanish treatment yields greater support for Puerto Rican political equality—particularly Puerto Rican evacuees’ right to vote in Florida—among Republicans compared with non-Republicans, white compared with nonwhite respondents, and among respondents who perceive Puerto Ricans as more American. I marshal evidence to support the argument that the Spanish language treatment marks Puerto Ricans as “foreign” and thus less subject to stereotypes about the cultural pathologies of an American racial underclass. Therefore, even if the marginal influences of dark skin and the Spanish language were to lead to greater stigmatization, the effect of both attributes together would not necessarily render an individual “doubly stigmatized.” For already ethnoracialized groups—especially Puerto Ricans who, as American citizens, may not carry the stigma of “illegal migrants”—this experiment suggests that perceived foreignness can sometimes offset the negative stereotypes that Americans may hold about members of a racially subordinated group.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. The first section introduces the case of Puerto Rico and Hurricane Maria and synthesizes what we know about American public opinion on Puerto Rico. I then situate this case within the literatures on racial and linguistic stereotypes. The next section describes the survey experimental design and an MTurk pretest. Finally, I present the results of the experiment (with additional descriptive analysis in Appendix A) before concluding with a discussion of their implications.

The Case of Puerto Rico and Hurricane Maria

After 400 years under Spanish rule, Puerto Rico became an unincorporated territory of the United States in 1898 as a result of the Spanish–American War. Puerto Ricans born on or off the island were granted American citizenship in 1917; they have been subject to a U.S. military draft, but they cannot vote in federal elections, do not have voting representation in Congress, and are exempt from federal personal income taxes. It wasn’t until 1948, 31 years after they had been granted American citizenship, that Puerto Ricans elected their first governor. Until then, governors had been appointed by the sitting president of the US. Shortly after, in 1952, a constituent assembly drafted the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, which was approved by the U.S. Congress and by the Puerto Rican popular vote. Establishing the Commonwealth granted Puerto Rico some autonomy, but it did not solve the centuries-old debate over the political status of the island—the single most salient issue in the Puerto Rican political arena. Six nonbinding status referenda have been held on the island during the past fifty years: in 1967, 1993, 1998, 2012, 2017, and 2020. Given that Congress ultimately has the power to modify the status of the island territory, these referenda serve the purpose of gauging public opinion on the matter at best and of providing the ruling party with campaign-season propaganda at worst. With the exception of the most recent referendum, in each occasion Puerto Ricans have been asked whether the island should remain a territory of the US, become a U.S. state, or become an independent country. In 2020 the ballot presented a simple yes-or-no question for the first time (i.e., “Should Puerto Rico be immediately admitted into the Union as a state?”). The status quo option won a majority of votes in the first three referenda, but in the three most recent ones, Puerto Ricans rejected the status quo in favor of statehood. However, an important caveat is that the most recent referenda have been riddled with controversyFootnote 6 and dismal turnout rates (23% in 2017).

The territorial status of the island has implications for the economic, political, and social life of its residents. The Jones-Shafroth Act, the same one that gave Puerto Ricans American citizenship in 1917, established that interest payments from bonds issued by the government of Puerto Rico are “triple tax exempt,” meaning that they are exempt from local, state, and federal income taxes. This provision has historically made Puerto Rican bonds attractive to investors. During the 1970s, the Puerto Rican government began to issue bonds as a solution to its growing debt. Over 40 years later, in 2014, when it became evident that the government was unable to pay its debt, Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch—three major credit-rating agencies—downgraded some of these government-issued bonds to “junk status.” The government then resorted to using its savings to pay for its debt. This chain of events led to the congressional enactment of the PROMESA law, which appointed an oversight board that assumed fiscal control of the island and has since implemented a series of austerity policies (White Reference White2016).

Thus, Puerto Rico was already in dire straits in September 2017, when it was devastated by two back-to-back hurricanes: Irma and Maria. Irma, one of the strongest hurricanes ever recorded in the Atlantic, affected the Eastern coast of the island and left thousands without electricity. Two weeks later, on September 20, Hurricane Maria traversed the island diagonally, killing approximately 3,000 people, destroying 70,000+ homes, provoking the biggest blackout in U.S. history, leaving 95% of the island without cell service, and causing at least $90 million in damage, making it the third costliest Atlantic hurricane since the early twentieth century (Fink Reference Fink2018; Staletovich Reference Staletovich2018). The crises—the debt and the hurricane—have also led to the exodus of record numbers of Puerto Ricans. According to a recent study by the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, an estimated 200,000 Puerto Ricans fled the island in the year after the hurricane (Caribbean Business 2018). According to the Census, more Puerto Ricans live on the U.S. mainland (5.1 million) than on the island itself (3.5 million). In the months leading up to November 2018, the influx of Puerto Ricans to states like Florida sparked debates about whether or not these evacuees would “turn the tide” in the midterm election (Flores, Hugo-Lopez, and Krogstad Reference Flores, Hugo-Lopez and Krogstad2018; Hagen Reference Hagen2018; Heath Reference Heath2018; Hohmann Reference Hohmann2018; Wilson Reference Wilson2018) and even whether they should be allowed to vote in the first place (Foran Reference Foran2018).

Both Puerto Ricans and Cubans—primarily political exiles revolting against the Spanish crown—have maintained a presence in the US (and New York City in particular) since well before the onset of American imperial rule (Hoffnung-Garskof Reference Hoffnung-Garskof2019; Perez Reference Perez2015; Valdés Reference Valdés2017). Since the end of the Spanish-American War (1898) and especially after Puerto Ricans received American citizenship in 1917, Puerto Rican migration to the U.S. mainland has increased dramatically. By the 1920s and 30s, over 50,000 Puerto Ricans lived in at least 45 states (Sánchez Korrol Reference Korrol and Virginia1983). What is referred to as Puerto Rico’s “Great Migration” began in the post-World War II period, largely due to the advent of low-cost airfare, economic privation in Puerto Rico, and active encouragement by the Puerto Rican government (specifically its migration bureau located in New York). In 1947 Life magazine ran a profile of this migration entitled “Puerto Ricans Jam New York,” which referred to Puerto Ricans showing up in droves at American welfare offices as well as the “crowded slums” and “tenement homes” in which Puerto Ricans lived. In popular culture, Wenzell Brown’s novels, one of which was entitled Run, Chico, Run (1953), prominently featured Puerto Ricans as juvenile delinquents, as did the famous American musical West Side Story (1957), which later became an award-winning film in 1961. These depictions of Puerto Ricans through crude stereotypes as an American racial underclass are, as Immerwahr (Reference Immerwahr2019, 281) states, “the first point of reference for mainlanders thinking about Puerto Rico.”

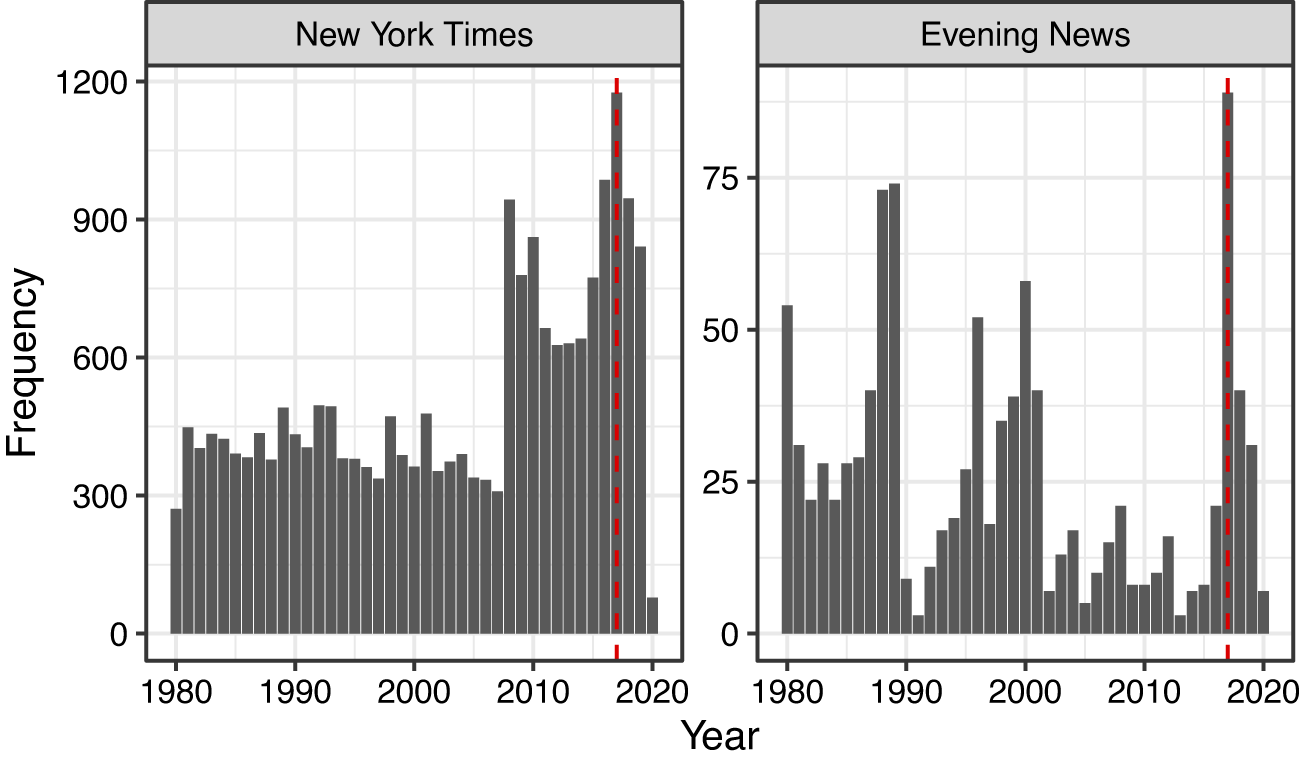

The debt crisis and the hurricane have once again brought questions about the governance of the island to congressional discussions and media headlines in the US. Media coverage of Puerto Rico has reached record highs in the past few years. Figure 1 shows fluctuations in media coverage of Puerto Rico over time as measured by the New York Times (left) and the Vanderbilt Television News Index (right). The panel on the left of Figure 1 shows that the peak level of New York Times coverage of Puerto Rico was in 2017, the year Maria struck the island. The panel on the right similarly shows that news coverage of Puerto Rico reached its highest point since 1990 in 2017. In the 15–20 years prior to the hurricane, Puerto Rico was mentioned sparingly on the national evening news. The New York Times, however, started to cover Puerto Rico more extensively around the time of the financial crisis (from 2008 onward).

Figure 1. Number of Times “Puerto Rico” Appeared on the New York Times and the Evening News, 1980–2020

Although, as mentioned above, Puerto Rico has long figured prominently in American public discourse and imagery, this heightened media attention might have contributed to increasing Americans’ awareness of the 120-year history binding Puerto Rico to the US.Footnote 7 A Morning Consult poll conducted a mere two days after the hurricane found that roughly half of Americans knew that people born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens (Dropp and Nyhan Reference Dropp and Nyhan2017).Footnote 8 Another poll conducted in October of the same year—around a month after the hurricane and likely at the height of the media boom on the topic—found that three-quarters (76%) of respondents knew that residents of Puerto Rico are indeed American citizens (DiJulio, Muñana, and Brodie Reference DiJulio, Muñana and Brodie2017).

In the months following the hurricane, scholars and journalists alike suggested that Trump’s “negligent response” in Puerto Rico, compared with the “all-hands-on-deck support seen by Harvey and Irma victims in Texas and Florida” only a few months prior, was driven by racial bias (Lluveras Reference Lluveras2017). Negrón-Muntaner (Reference Negrón-Muntaner2017), for instance, argues that, “when local leaders criticized him for [the slow response], Trump defended himself by invoking century-old racial stereotypes of Puerto Ricans as lazy and ingrates who ‘wanted everything to be done for them.’” These claims are reminiscent of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005. According to the Pew Research Center (Doherty Reference Doherty2015), “the tragedy had a powerful racial component” from the start. As Iyengar and Morin (Reference Iyengar and Morin2006) put it, “natural disasters are typically occasions for political unity; after witnessing widespread death and destruction Americans typically reach for their wallets rather than engage in rancorous debates over fixing responsibility and blame.” After Katrina, however, long-standing debates about poverty and race quickly rose to the surface. Iyengar and Morin (Reference Iyengar and Morin2006) conducted an experiment in which they exposed subjects to racial cues. In one intervention, they presented subjects with a typical story about a hurricane victim and varied the victim’s race. The findings of the experiment revealed that participants recommended lower levels of financial assistance for dark-skinned hurricane victims of different ethnicities (Black, Hispanic, and Asian)—compared with light-skinned victims of the same ethnic groups—and recommended the shortest period of assistance for African Americans. The authors conclude that “framing disasters in ways that evoke racial stereotypes can make people less supportive of large-scale relief efforts.”

In a national poll conducted in September 2005, one week after Katrina, 66% of African Americans said that “the government’s response to the situation would have been faster if most of the victims had been white,” whereas just 17% of whites agreed with this statement (Doherty Reference Doherty2015). Similarly, a nationally representative poll conducted about two weeks after Maria asked respondents whether ethnicity and poverty affected the recovery effort in Puerto Rico. Overall, respondents were split in their opinions: 46% said the federal government’s response would be moving faster if the hurricane had happened in a wealthier place with fewer Hispanic people, whereas 44% said that ethnicity and poverty had not affected the recovery effort. When broken down by partisanship, however, the poll revealed large disparities. A majority (69%) of Democrats thought that ethnicity and poverty played a role in the federal government’s response in Puerto Rico, whereas only 12% of Republicans felt the same.

These survey data suggest that disaster relief has become (or is becoming) a racialized policy issue. Although a large segment of the population perceives disaster relief for Puerto Rico as racialized, perhaps the strongest evidence for the racialization of disaster relief is the 83% of whites and 80% of Republicans who claim that it is not racialized. Consider, for example, one of the most racialized issues in the US today: police violence. Survey data suggests that a majority of Republicans believe that police violence is unrelated to race (Public Agenda 2020). The steadfast adherence of many Americans to a “colorblind” lens, much like the issue of police violence, illustrates how contentious the issue of race is for disaster relief in Puerto Rico and elsewhere.

By randomly exposing survey respondents to two different types of hurricane victims, I am able to assess whether respondents’ preferences regarding relief efforts and Puerto Rican political equality are driven by the victims’ ethnoracialized characteristics (namely, skin tone and language). The case of Puerto Rico adds an interesting layer to this question. Puerto Ricans, like many Latinos, are majority Spanish-speaking in addition to being phenotypically heterogeneous. How do these two features together shape American public opinion?

The Effects of Skin Color and Language on Policy Preferences

Skin color and language are two of the main traits individuals draw upon to make sense of the social and political world (Kinzler et al. Reference Kinzler, Shutts, DeJesus and S. Spelke2009). In the context of the US, individuals draw on both traits as cues regarding one’s nationality, regional membership, ethnic group, and social status or class (Labov Reference Labov2006). Therefore, the skin color and language of a person sharing a message can be powerful social conveyors of information regardless of the content of the message itself. Yet, the intersectional relationship between these two identities as possible bases of discrimination is unclear. In the case of Hurricane Maria, are Americans’ opinions regarding relief policy and substantive political equality driven by the skin color and language of the victims who would benefit from such aid? How do the effects of these two traits intersect? This section addresses the theoretical expectations underlying these questions.

Theoretical Framework

In this paper, I conceive of racialization as a process that is multidimensional—that is, a “bundle of sticks” (Sen and Wasow Reference Sen and Wasow2016)—focusing specifically on the dimensions of skin color and language. By describing skin color as a dimension of racialization, I invoke the distinction between racism and colorism.Footnote 9 As Hunter (Reference Hunter2005; Reference Hunter2007) explains, racism refers to the systemic subordination of individuals who are marked as belonging to a racial group regardless of variation in group members’ physical appearances. Colorism, by contrast, is based solely on skin color, which often shapes the intensity of discrimination and subordination that members of a racial group experience (Hunter Reference Hunter2007). Historically, Americans have ascribed a social and political hierarchy on the basis of skin color. As Hunter (Reference Hunter2007, 238) writes, “dark skin represents savagery, irrationality, ugliness, and inferiority. White skin […] is defined by the opposite: civility, rationality, beauty, and superiority.” Among individuals racialized as Puerto Ricans (or as Latinos), in particular, a range of scholars argue that material privileges accrue to light-skinned (relative to dark-skinned) individuals, which in turn shape Latinos’ life outcomes and their own racial identifications (Golash-Boza and Darity Reference Golash-Boza and Darity2008; Hall Reference Hall2004, Reference Hall2018; Quiros and Dawson Reference Quiros and Dawson2013).

More abstractly, both skin color and language map onto the formal theoretical framework developed by Kim (Reference Kim1999; Reference Kim2000) and more recently expounded upon by Zou and Cheryan (Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). In this framework, racial and ethnic subordination exists along two dimensions: one is inferiority–superiority and the other is foreignness–Americanness. White Americans, for example, are marked as superior to other ethnoracial groups, as well as quintessentially American. In contrast, Asian Americans, for example, are marked as inferior to white Americans (although sometimes superior in specific domains (Cheryan and Bodenhausen Reference Cheryan, Bodenhausen, Caliendo and McIlwain2020) but superior to Black Americans; yet Asian Americans are simultaneously marked as foreign with respect to not only white but also Black Americans (Xu and Lee Reference Xu and Lee2013; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). Latinos, too, can be similarly positioned relative to others along these two axes. To be clear, there are other relevant dimensions that intersect with the inferiority–superiority and foreignness–Americanness dimensions such as gender, class, and sexuality (Bank Muñoz Reference Bank Muñoz2008; Fields and Fields Reference Fields and Fields2014; Glenn Reference Glenn2004); however, inferiority–superiority and foreignness–Americanness are the primary dimensions plausibly manipulated by the experiment’s skin color and language treatments.

The dimension of inferiority–superiority, operationalized via skin color, appears to have an effect, all else equal, on Americans’ policy preferences both within and between racialized groups. Such colorism manifests in the form of electoral support (or lack thereof) for Black candidates running for public office (Hochschild and Weaver Reference Hochschild and Weaver2007; Lerman, McCabe, and Sadin Reference Lerman, McCabe and Sadin2015; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993; Weaver Reference Weaver2012) and the punitiveness of prison sentences (Blair, Judd, and Chapleau Reference Blair, Judd and Chapleau2004; Eberhardt et al. Reference Eberhardt, Davies, Purdie-Vaughns and Johnson2006; Viglione, Hannon, and DeFina Reference Viglione, Hannon and DeFina2011), among a range of other outcomes. Skin color—and specifically how political elites portray (and manipulate) the features of individuals who would benefit from public policies—can therefore serve as a subtle cue that invokes latent stereotypes in the minds of Americans, without overt expressions of racism per se (Bobo and Kluegel Reference Bobo and Kluegel1993; Hurwitz and Peffley Reference Hurwitz and Peffley2005; Hutchings and Jardina Reference Hutchings and Jardina2009). Insofar as skin tone does, all else equal, activate latent stereotypes that Americans have about racial groups’ pathological behaviors, then one would expect the marginal effect of race to decrease support for Puerto Rico hurricane relief as well as for Puerto Rican statehood and the right for Puerto Rican evacuees to vote in Florida. In the context of former President Donald Trump’s widely publicized and inadequate response to the hurricane, which was justified via tropes commonly used to describe members of American racial underclasses—for example, laziness and corruption (Negrón-Muntaner Reference Negrón-Muntaner2017)—one would also expect that, all else equal, darker skin increases Americans’ support for Donald Trump’s response to Hurricane Maria.

One would also expect the dimension of foreignness–Americanness, operationalized via Spanish or English language, to have an effect, all else equal, on Americans’ policy preferences. As of 2016, 40 million U.S. residents ages five years and older speak Spanish at home (U.S. Census Bureau 2017). However, the English language remains a central component of American identity (Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2005; Reference Schildkraut2010). Native-born Americans have expressed particular concern with the public use of Spanish, and this concern, or even anger, is associated with negative views of immigration (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2014). In a recent poll, for example, 45% of respondents said that “people need to be more careful about the language they use to avoid offending people with different backgrounds” (Pew Research Center 2018a). In an earlier survey, when asked specifically about encounters with non-English speaking immigrants, 38% of respondents said they were bothered by such encounters (Pew Research Center 2018b).

In short, language—and the English language’s status as the quintessentially American language—is perhaps the strongest indicator of one’s foreignness or Americanness. Language also operates as perhaps the most common indicator of one’s degree of assimilation (Citrin Reference Citrin1990; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2011; Newman, Hartman, and Taber Reference Newman, Hartman and Taber2012), although other measures—such as food and clothing—are indicative too (Ostfeld Reference Ostfeld2017). Ostfeld (Reference Ostfeld2017) shows that immigrants who evince cultural and linguistic similarity with putative American culture will be less subject to discriminatory attitudes. English, even if accented, can increase support for pro-immigration policies (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2015). Insofar as Americans value the extent of Anglo-American assimilation of Puerto Ricans, then one would expect, all else equal, for the Spanish language treatment to decrease Americans’ support for Puerto Rican statehood and for Puerto Rican evacuees’ right to vote in Florida. For this same reason, one might expect the Spanish language to increase approval of Trump’s response to Hurricane Maria given his public and frequent invocations of a “Latino threat” (Chavez Reference Chavez2013). One would also expect the Spanish treatment to have a negative effect on support for hurricane relief, although potentially through a different mechanism—namely, Americans’ support for putatively domestic rather than foreign spending (Page and Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro2010).

The theoretical framework I describe above enables one to assess the marginal effects of the inferiority–superiority and foreignness–Americanness dimensions. However, I conceive of ethnoracial subordination along these two dimensions through an intersectional lens. In the context of this study, intersectionality, a term coined by Crenshaw (Reference Crenshaw1989; Reference Crenshaw1991), posits that both skin color and language need not combine additively to shape Americans’ attitudes toward ethnoracial minorities (Glenn Reference Glenn1992). Instead, the degree of foreignness–Americanness (operationalized via Spanish or English language) may depend on the degree of perceived inferiority–superiority (operationalized via skin color) and vice versa. As Dávila (Reference Dávila2008, 1) writes, Latinos are (often simultaneously) represented in public discourse as “illegal, tax burden” but also as “family-oriented, hard working.” The specific stereotypes that emerge in the minds of Americans will likely depend on the interaction between skin color and language. For example, an individual with Afrocentric features who speaks English might be marked as more American, which may, in turn, attract stereotypes (laziness, stupidity, criminality, sexual promiscuity) associated with the “dark ghettos” (Shelby Reference Shelby2007; Reference Shelby2016) of the American racial underclass. In contrast, speaking Spanish might mark an individual with Afrocentric features as less American and thus render such features less associated with the perceived pathologies of a racial underclass. Even if the marginal effects of dark skin and Spanish language lead to greater stigmatization, overall stigmatization may not be simply skin color plus language.

Within this theoretical framework, Puerto Rico presents itself as a theoretically rich case. On the one hand, as Grosfoguel (Reference Grosfoguel1999, 244) writes, “Puerto Ricans and African-Americans [sic] are not simply migrants or ethnic groups, but rather colonial/racialised subjects in the USA.” Rodríguez Domínguez (Reference Domínguez and Victor2005) traces this ethnoracialization of Puerto Ricans as a domestic underclass to the period from the 1890s (right after the US’s occupation of Puerto Rico) to the 1930s. Since this period, Puerto Ricans, much like Black Americans, have been ethnoracialized according to cultural pathologies of the “dark ghetto” (see Ramos-Zayas Reference Ramos-Zayas2003; Reference Ramos-Zayas2004). The canonical book by Oscar Lewis, La Vida (Reference Lewis1966), which would go on to win a National Book Award in 1967, presents Puerto Ricans in both New York and San Juan as the archetypal group that suffers from a “culture of poverty” (Lewis Reference Lewis1966). Although Puerto Ricans have been ethnoracialized in ways similar to those of Black Americans (Grosfoguel Reference Grosfoguel1999), many Americans also interpret Puerto Ricans as a foreign migrant group owing to Puerto Rico’s political status, as well as Puerto Ricans’ language and culture, which differ from those of the majority of Americans.

Indeed, ever since the US’s occupation of Puerto Rico in 1898, Puerto Rico has remained absent from the American “logo map” (Anderson Reference Anderson2006) that is reproduced in official government documents, school textbooks, and other media. Puerto Ricans occupy an ambiguous position as both a racialized underclass and a foreign (potentially migrant) group in the minds of Americans. Therefore, Puerto Rico is an ideal case for assessing the marginal and interactive effects of inferiority–superiority and foreignness–Americanness in the racialization of putatively race-neutral policies.

Survey Experimental Design

To estimate the causal effects of skin color and language on white Americans’ attitudes toward Puerto Rico, I designed and implemented a survey experiment (N = 1,000) within the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study. I had two actors portray hurricane victims and give general information about the damage the storm caused and the island’s needs one year after the disaster.Footnote 10 A videographer recorded the actors’ message in an area that had been visibly affected by the hurricane. Figures 1 and 2 in Appendix C show still images from the videos.

Survey respondents were randomly assigned to watch one of four 30-second videos that explain the needs of Hurricane Maria victims in Puerto Rico. In this 2 × 2 factorial design, I define treatment conditions on two dimensions: skin tone and language. Both treatments are binary contrasts, which (as is particularly relevant for the skin tone treatment) do not account for finer gradations that often serve as markers of social difference. Table 1 shows the four treatment conditions. The two actors who delivered the treatments share the same sex, age, clothing, accent, and level of English fluency.

Table 1. Treatment Conditions

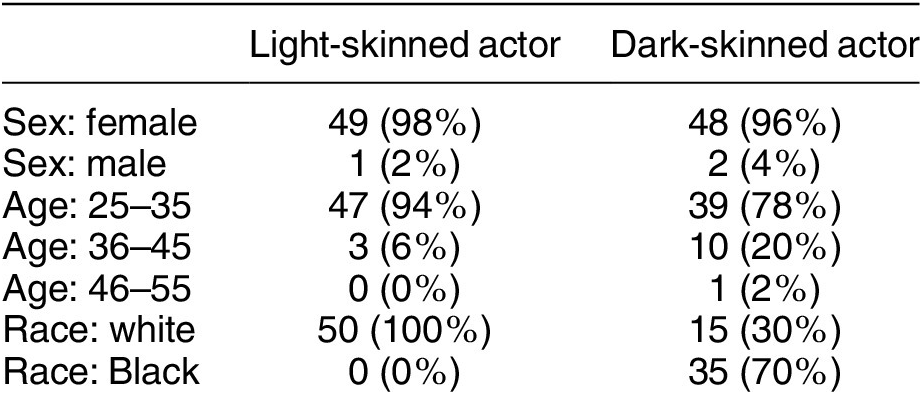

To ensure that the only appreciable difference between the two actors is skin tone—one of them has dark skin and the other has light skin—I conducted a pretest on Mechanical Turk. In this pretest, I provided no information other than the two actors’ photos; the pretest contained no mention of Puerto Rico, Hurricane Maria, or other such information. I then randomly assigned 100 respondents to view a picture of one of the two actors from the video intervention. I asked the respondents to describe the actors in the pictures in terms of their sex, age, and race. The results in Table 2 show that the overwhelming majority of respondents correctly classified both actors as “female” and described the light-skinned actor as “white.” A smaller percentage, but still a large majority (70%), of respondents described the dark-skinned actor as “Black.” There is also a 16 percentage-point difference in the perceived ages of the actors: respondents perceived the light-skinned actor to be slightly younger than the dark-skinned actor, although both actors were of the same age. Overall, the largest perceived difference between the two actors is their race.

Table 2. Pretest Results: Demographics of the Two Hired Actors

To estimate the effects of skin tone and language, both actors impart the same message in every video, but each of them acts out one version in English and one (otherwise identical) version in Spanish. The videos were all filmed in the same location at the same time, and they were edited to include English subtitles. Even though both English and Spanish videos have subtitles, the cognitive task in the Spanish language video is different, which is, in many ways, a feature rather than a bug that constitutes the Spanish (foreign) language treatment. The actors were similarly dressed and trained to give the same statement using similar body language and accent. The treatments, then, are the skin tone of the actors and the language in which they share information about Hurricane Maria. Table 3 shows the script the actors followed in the intervention videos.

Table 3. Script Used in Video Intervention

The CCES Common Content (N = 60,000) provides information on respondents’ demographic characteristics as well as their partisan affiliation. A subset of 1,000 respondents participated in this experiment and were exposed to the video intervention described above. In addition to respondents’ race and party identification, this portion of the survey includes three pretreatment questions that measure respondents’ knowledge about Puerto Ricans’ citizenship status and the main language spoken in the island.

I asked respondents, “To the best of your knowledge, are people born in Puerto Rico citizens of the United States or not?” The response categories were simply “Yes” or “No.” Finally, respondents answered the following question: “To the best of your knowledge, what is the main language spoken in Puerto Rico?” The potential answers were “Mostly English,” “Mostly Spanish,” or “Both English and Spanish.” The survey also includes four outcome measures related to Puerto Rico, as detailed in Table 4. All of the outcomes are measured on a binary scale.

Table 4. Measurement of Outcomes

In addition to the outcome variables described above, I also measured a battery of baseline demographic (e.g., age and family income) and political participation (e.g., voting in 2016 election) variables. The 2018 CCES Team Module respondents resemble those of the 2018 American National Election Studies in terms of age, sex, educational attainment, race, region of residence, family income, participation in the 2016 presidential election, and vote choice in 2016. See Table 5 for a detailed comparison of the two survey samples.

Table 5. Comaprison of CCES and ANES Samples

Two pretreatment covariates are of special interest for descriptive analysis: respondents’ knowledge of Puerto Ricans’ language and citizenship. Only 31.5% of respondents correctly identified Spanish as the main language spoken in Puerto Rico. Most respondents identified Puerto Rico as largely bilingual, but in reality only about 20% of the island’s residents report that they speak English proficiently. That number drops to around 5% in rural areas (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Most respondents (81%), on the other hand, were correct in noting that Puerto Ricans are American citizens. This number is surprisingly high, considering that polls on the matter placed that percentage between 43% and 52% (Dropp and Nyhan Reference Dropp and Nyhan2017; Frankovic Reference Frankovic2016). However, this increase in knowledge is consistent with more recent, posthurricane polls (DiJulio, Muñana, and Brodie Reference DiJulio, Muñana and Brodie2017) and can therefore plausibly be attributed to the increased salience of Puerto Rico in media headlines following the hurricane.

Results

In this section, I present two sets of results: the estimated marginal effects of the race and language treatments on support for Puerto Rico and the heterogeneous effects of each treatment by partisanship, race, knowledge of Puerto Ricans’ citizenship, and beliefs about the primary language that Puerto Ricans speak.

Marginal Effects of Skin Color and Language

For the marginal effects of each treatment, the targets of interest are the average difference in outcomes if respondents were exposed to (1) the dark-skinned informant versus the light-skinned informant and (2) the Spanish-speaking informant versus the English-speaking informant. I first rescale the observed potential outcomes as a linear function of a set of baseline covariates. This method reduces variance of potential outcomes that is uninformative about the causal effect and thereby increases the power to detect effects (Rosenbaum Reference Rosenbaum2002).

I rescale the observed outcomes for all

![]() $ i\hskip0.35em =\hskip0.35em 1,\dots, \mathrm{1,000} $

respondents in the experiment as follows:

$ i\hskip0.35em =\hskip0.35em 1,\dots, \mathrm{1,000} $

respondents in the experiment as follows:

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{y}_i-\Big({\hat{\beta}}_0+{\hat{\beta}}_1{x}_{i, age}+{\hat{\beta}}_2{x}_{i, female}+{\hat{\beta}}_3{x}_{i, educ}+{\hat{\beta}}_4{x}_{i, White}\\ {}+{\hat{\beta}}_5{x}_{i, south}+{\hat{\beta}}_6{x}_{i, republican}+{\hat{\beta}}_7{x}_{i, trump}+{\hat{\beta}}_8{x}_{i, income}\\ {}+{\hat{\beta}}_9{x}_{i, citizen}+{\hat{\beta}}_{10}{x}_{i, language}\Big)\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{y}_i-\Big({\hat{\beta}}_0+{\hat{\beta}}_1{x}_{i, age}+{\hat{\beta}}_2{x}_{i, female}+{\hat{\beta}}_3{x}_{i, educ}+{\hat{\beta}}_4{x}_{i, White}\\ {}+{\hat{\beta}}_5{x}_{i, south}+{\hat{\beta}}_6{x}_{i, republican}+{\hat{\beta}}_7{x}_{i, trump}+{\hat{\beta}}_8{x}_{i, income}\\ {}+{\hat{\beta}}_9{x}_{i, citizen}+{\hat{\beta}}_{10}{x}_{i, language}\Big)\end{array}} $$

where

![]() $ {\hat{\beta}}_0,\dots, {\hat{\beta}}_{10} $

are fit via ordinary least squares regression.Footnote

11 By using covariates only to rescale and thus reduce variance in potential outcomes, standard errors and p-values remain based on the random assignment of treatment. Tables 6 and 7

Footnote

12 present the results for the marginal effects of the race and language treatments, respectively.

$ {\hat{\beta}}_0,\dots, {\hat{\beta}}_{10} $

are fit via ordinary least squares regression.Footnote

11 By using covariates only to rescale and thus reduce variance in potential outcomes, standard errors and p-values remain based on the random assignment of treatment. Tables 6 and 7

Footnote

12 present the results for the marginal effects of the race and language treatments, respectively.

Table 6. Effect of Skin Tone on Attitudes toward Puerto Rico

Note: lwr = lower p-value, and upr = upper p-value. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 7. Effect of Language on Attitudes toward Puerto Rico

Note: lwr = lower p-value, and upr = upper p-value. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

The estimated treatment effect of the dark-skinned informant is close to zero for the outcomes of support for Puerto Rican statehood and approval of Trump. For the federal aid outcome, the average outcome in the dark-skinned condition is 2.8% higher than in the light-skinned condition. Support for voting in Florida, however, is 1.7% smaller in the dark-skinned condition relative to the light-skinned condition, but it is still relatively consistent with the sharp null hypothesis of no effect. Only for the outcome of federal aid would one be able to reject the sharp null hypothesis of no effect in favor of the alternative of a positive effect at the 10% level.

These results are consistent with extant research, which finds the absence of a strong relationship, on average, between skin color and preferences toward immigrants (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Soroka, Iyengar and Valentino2012; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2015; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Jackman, Messing, Valentino, Aalberg, Duch and Hahn2013; Sniderman et al. Reference Sniderman, Piazza, Tetlock and Kendrick1991). Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2015) in particular finds small and statistically indistinguishable effects of skin tone manipulations on policy preferences (attitudes toward immigration, in his case). He concludes that the skin tone cue may influence perceptions about where a person is from but that cue does not translate to shifts in policy preferences. At least in terms of the marginal effect of skin tone, this null finding provides further support for the claim that the primacy of skin tone in shaping attitudes toward immigration is overstated (Harell et al. Reference Harell, Soroka, Iyengar and Valentino2012; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2015; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Jackman, Messing, Valentino, Aalberg, Duch and Hahn2013).

The positive effect of the skin color treatment on the federal aid outcome (but not others) may reflect the role that skin color plays in Americans’ perception of neediness. For example, Americans’ conceptions of dark-skinned Africans as in need of American paternalism makes Americans more likely to support redistributive aid to Africans than to Europeans (Baker Reference Baker2015). If indeed such a mechanism were at play, then we would expect an effect of the skin color treatment on only the federal aid outcome, not the other outcomes pertaining to substantive political equality for Puerto Ricans.

For the language treatment, I find that, relative to subjects who saw the English-language video, respondents who saw the Spanish-language video were 2.8 percentage points less likely to support increased federal spending on disaster relief for Puerto Rico. Similarly, respondents who saw the Spanish-language video were 4.1 percentage points less likely to think that Puerto Rico should become the 51st state of the Union and 3.8 percentage points less likely to agree that Puerto Ricans who were displaced to Florida by the hurricane should be allowed to vote in that state. When I test the sharp null hypothesis of no effect of the language treatment—that is, that all respondents would have given the same answer if shown the English or Spanish videos—I am able to reject the sharp null hypothesis in favor of the alternative of a negative effect at the 0.10 level for all three outcomes. However, this effect does not appear to extend to approval for President Trump’s handling of the disaster.

These results are consistent with expectations in much of the extant literature. The literature on linguistic stereotypes suggests that individuals are more likely to be persuaded by arguments made by in-group members (Mackie and Cooper Reference Mackie and Cooper1984) and that Americans in particular are more likely to support spending on domestic as opposed to foreign affairs (Page and Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro2010). Hearing about the hurricane in Spanish might have made respondents view the crisis in Puerto Rico a foreign one. These results—especially the negative effect of the Spanish-language treatment on respondents’ support for Puerto Rican statehood and Puerto Rican evacuees’ right to vote in Florida—are also consistent with the literature on the primacy of English as a marker of American identity. These estimates are small and are not all statistically significant at the 0.05 level; yet it is worth noting that they represent the effect of being exposed to the Spanish language treatment for only 30 seconds. Prolonged or repeated exposure over time could result in larger shifts in opinion.

Overall, the marginal effect of language is greater than that of race. One likely reason for this finding, which I will clarify further in the immediately succeeding section, is that Puerto Ricans are an already racialized group in the minds of many Americans. Respondents are aware of Puerto Ricans’ status as American citizens but far less aware of the primacy of the Spanish language in Puerto Rico. Therefore, the Spanish language treatment likely leads to greater shifts on the foreignness–Americanness dimension than the skin color treatment yields on the inferiority–superiority dimension.

Heterogeneous Effects of Skin Color and Language

In this section, I focus on the heterogeneous effects of skin color and language by four primary baseline covariates: (1) belief about the primary language in Puerto Rico (“both English and Spanish” and “mostly English” versus “mostly Spanish”), (2) knowledge of Puerto Rican citizenship (“yes” or “no”), (3) party identification (either Republican or non-Republican), and (4) race (either white or nonwhite). Given this paper’s intersectional framework, I now describe expectations about the heterogeneous effects of skin tone and language on support for Puerto Rico—namely, support for federal aid, Puerto Rican statehood, voting rights for Puerto Rican evacuees in Florida, and disapproval of President Trump’s handling of the disaster.

Covariates (1) and (2) approximate the extent to which a respondent views Puerto Ricans as American or foreign. The dark-skin treatment should lead to less support for Puerto Rico among respondents who view Puerto Ricans as more American (and thus more subject to stereotypes about the cultural pathologies of an American racial underclass). However, insofar as perceived foreignness can offset such stereotypes, the Spanish treatment should yield more support for Puerto Rico among respondents who perceive Puerto Ricans as more American.

Covariates (3) and (4) do not approximate the extent to which Puerto Ricans are perceived as American or foreign. Indeed, as the descriptive statistics show, perceptions of Americanness and foreignness are similar across party and race subgroups. However, given survey data that suggest as much, covariates (3) and (4) do plausibly approximate the extent to which a respondent harbors negative stereotypes about an American racial underclass. Thus, the dark-skin treatment should lead to less support for Puerto Rico among respondents who harbor such negative stereotypes relative to those who do not. In contrast, the Spanish-language treatment, insofar as perceived foreignness can offset stereotypes about a racial underclass, should increase support among respondents who harbor these stereotypes relative to respondents who do not. The logic is the same for covariate (4): insofar as white respondents harbor stereotypes about a racial underclass more than do nonwhite respondents, the dark-skin treatment ought to yield less support and the Spanish-language treatment ought to yield greater support for Puerto Rico among white compared with nonwhite respondents.

Focusing first on the heterogeneous effects of skin tone, Table 8 presents the results across the four aforementioned covariates.

Table 8. Heterogeneous Effects of Skin Tone

Note: lwr = lower p-value, and upr = upper p-value. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

As Table 8 shows, among respondents who perceive Puerto Ricans as English-speakers, the dark-skin treatment induces greater support for Trump compared with respondents who perceive Puerto Ricans as speaking Spanish. Likewise, the estimated effect of dark skin on support for Trump is greater among respondents who perceive Puerto Ricans as American citizens compared with those who do not. In other words, the estimated effect of dark skin on support for Trump’s handling of the disaster, which translates to less support for Puerto Rico, is greater among respondents who perceive Puerto Ricans as more American—and thus characterized by the tropes of laziness and corruption that Trump used to justify his administration’s lackluster response to the hurricane—as opposed to more foreign. Dark skin also produces less support for Puerto Rico among respondents who perceive Puerto Ricans as American citizens for the outcomes of support for federal aid, statehood, and voting rights in Florida.

The negative effect of dark skin on support for Puerto Rican statehood and voting in Florida is significantly greater among Republicans than among non-Republicans. This significant result is unsurprising given that survey data suggest Republicans hold more negative stereotypes about Black Americans. These heterogeneous effects are likely driven primarily by such differences in stereotypes rather than non-Republicans’ harboring greater racial paternalism (see Baker Reference Baker2015, referred to above). The estimated effect of dark skin on support for federal aid—the most plausible outcome for which the mechanism of racial paternalism would be at work—is small but positive for both Republicans and non-Republicans. The significant heterogeneous effects of the other outcomes are driven by large negative effects among Republicans and negligible effects among non-Republicans. If the mechanism of racial paternalism were the primary driver of this result, then we would presumably be more likely to observe a negligible effect among Republicans and a larger positive effect among non-Republicans.

I now turn to heterogeneous effects of the Spanish language treatment across the four primary covariates described above. Table 9 above presents these results.

Table 9. Heterogeneous Effects of Language

Note: lwr = lower p-value, and upr = upper p-value. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

The results in Table 9 suggest that perceived foreignness can offset stereotypes about the cultural pathologies of an American racial underclass. Although falling just shy of the statistical significance threshold, the effect of the Spanish treatment yields less support for Trump (i.e., more support for Puerto Rico) among respondents who perceive Puerto Ricans as English speakers compared with the effect of the Spanish treatment among respondents who already perceive Puerto Ricans as Spanish speakers. The same logic appears to be at work for the results among respondents who perceive Puerto Ricans to be American citizens compared with those who do not. The estimated effect of the Spanish treatment yields greater support for Puerto Rico—federal aid, statehood, and voting rights for Puerto Rican evacuees in Florida—among respondents who perceive Puerto Ricans as American citizens.

There are two interlinked explanations for these results. First, Puerto Ricans are already legible in the minds of respondents as an American (or at least quasi-American) group that is potentially subject to racial stereotypes. To buttress this claim, note that only 73% of respondents perceived the informant with light skin as white and only 23% of respondents perceived the informant with dark skin as Black. This finding is in direct contrast to those from the the pretest in which 100% of respondents perceived the same informant with light skin as white and 73% perceived the same informant with dark skin as Black. In the pretest, however, only the photos of the two informants were presented to respondents without any mention of Puerto Rico. When the context of Puerto Rico is explicit, respondents perceive the informants as white and Black at much lower rates, which suggests that Puerto Rican is an already racialized group unto itself.

The perceived cultural pathologies of Puerto Ricans as a domestic racial group, as clearly laid out by Grosfoguel (Reference Grosfoguel1999), are in direct opposition to cultural traits of industriousness and strong work ethic often associated with “immigrant values” (Lapinski et al. Reference Lapinski, Peltola, Shaw and Yang1997) of which Cuban-Americans (perceived as predominantly white, but Spanish speaking) are the apotheosis in the minds of many Americans (Barrios Reference Barrios2011; Duany Reference Duany1999). Thus, given the cultural pathologies associated with Puerto Ricans, much like Black Americans, the Spanish-language treatment may render Puerto Ricans more foreign and thus less subject to such pathologies. Even if not yet assimilated, foreign migrants are in principle more assimilable to “American values” relative to an already racialized American underclass.

Second, foreignness can also signal stereotypes of illegality. However, after measuring beliefs about Puerto Ricans’ perceived Americanness, the script of the intervention informs all respondents that Puerto Ricans are legally American citizens.Footnote 13 Thus, Puerto Ricans’ perceived foreignness—and its signals of positively viewed cultural traits relative to those of an American underclass—may not come with the associated baggage of illegality that often plagues other ethnoracial groups (e.g., Mexican Americans).

This logic above also explains the heterogeneous effects of the Spanish treatment by party (Republican versus non-Republican). Insofar as Afrocentric features and the Spanish language are both stigmatized, then one might expect Spanish to yield lower support for Puerto Rico among Republicans than among non-Republicans. Yet the Spanish treatment makes Republicans more likely to support voting in Florida, as Table 9 above shows. However, the same heterogeneous effects by party do not exist for the Puerto Rican statehood outcome. The crucial distinction between the statehood and voting rights for Puerto Rican evacuees outcomes is that the latter pertains specifically to migrants who have traveled from Puerto Rico to the U.S. mainland. The extension of rights to specifically Puerto Rican migrants suggests a desire to assimilate foreign but still assimilable Puerto Ricans. In contrast, granting statehood to Puerto Rico—without and not in the context of concomitant migration from Puerto Rico to the mainland US—potentially suggests a Hispanicizing and so-called “browning of America” (Sundstrom Reference Sundstrom2008) rather than the assimilation of a foreign migrant group into a predominantly white, Anglophone American polity.

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper studies the effects of racial and linguistic stereotypes on attitudes toward hurricane relief in Puerto Rico. It advances previous studies by being the first to (a) explore attitudes toward Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans on the island and (b) disentangle the effects of race- and language-based stereotypes on preferences over a putatively race-neutral policy, which in turn sheds light on how such policies become racialized. I describe the events that transpired in the aftermath of the hurricane and contextualize the natural disaster within the ongoing fiscal crisis and the 120-year-old colonial relationship with the US. After situating this case in the literature on the effects of stereotypes on policy preferences, I explain the design of the survey experiment in which I had two actors, demographically identical save for skin complexion, portray hurricane victims and give information about the needs of the island in either English or Spanish.

From this randomized experiment, I have shown that the marginal effect of the Spanish language on American public opinion toward Puerto Rico is negative. Receiving information about Hurricane Maria from a Spanish-speaking victim led to decreased support for federal aid, statehood, and voting rights. The estimated treatment effects on the full sample are small, but they represent the effect of being exposed to the Spanish language for only 30 seconds. However, most importantly, I show how race, skin-color, and language intersect in ways that a focus on their marginal effects alone would miss.

There are, of course, many limitations of this study: first, this paper provides only one contrast of comparatively lighter versus darker skin tone. Although skin color—and the meanings Americans ascribe to it—are best conceived as a continuum, the experimental design considers only a binary contrast between one informant with light skin and another with darker skin. Such a contrast does not address skin tone as a continuum or the range of phenotypic features among Puerto Ricans in particular and Latinos in general.

Second, the survey measures respondents’ beliefs about Puerto Ricans’ citizenship and primary language, but it does not gauge respondents’ knowledge of Puerto Rico’s economic situation in 2017. Although I do present evidence that Puerto Rico’s economic crisis was salient in the lead-up to Hurricane Maria, as measured through news coverage, the survey experiment is unable to assess the ways in which beliefs about poverty in Puerto Rico condition the effects of the skin color and language treatments.

Third, this paper takes an intersectional approach, but only along two of many dimensions, which include gender, sexuality, class, and others. Both informants in the experiment identified (and were identified by respondents) as female. Yet the results could very well have been different had the informants been male, especially because stereotypes about inferiority–superiority and foreignness–Americanness may operate differently depending on gender. Although the role of gender does not impugn the internal validity of the experiment, it is an important scope condition to keep in mind. Future research will hopefully unravel the ways in which other social identities interact with skin color and language, perhaps also in counterintuitive ways.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000971.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DSCREK.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Thomas Leavitt, Robert Y. Shapiro, Justin H. Phillips, Fredrick C. Harris, Yamil Vélez, and David Jones for their invaluable advice in the many stages of this project. I am also grateful to the audiences at the University of Illinois–Urbana-Champaign, the University of California–Berkeley, the University of Chicago, and the APSA and MPSA annual meetings, as well as the editors and anonymous reviewers of this journal, for their critical comments and suggestions.

FUNDING STATEMENT

I thank Columbia University’s Center on African American Politics and Society, Division of Social Sciences, and Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy for providing funding for this research.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

Ethical Standards

The author declares the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by Columbia University’s Institutional Review Board and certificate numbers are provided in the appendix. The author affirms that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.