In spite of decades of research into the Terracotta Army of the First Emperor of China, many questions remain about how, where, and by whom these famous sculptures were made. Recently Patrick Quinn, Shangxin Zhang, Yin Xia, and Xiuzhen Li compared the results of microscopic analyses of the larger than life-sized clay statues and other ceramic artefacts recovered from the mausoleum [Reference Quinn1]. All ceramic specimens were prepared as 30 μm sections and were analyzed by transmission polarized microscopy with magnifications up to 400×. Petrographic analysis focused on the nature of particulate inclusions, clay matrix, and voids. Quantitative analyses were also performed.

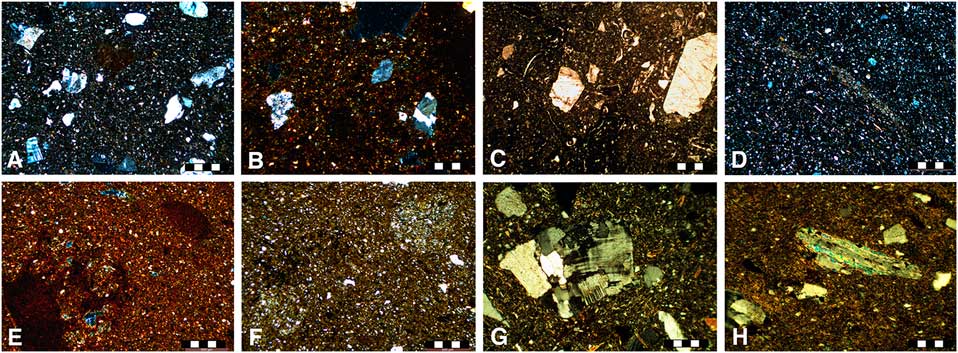

All sections of the samples appear to have been produced with a clay paste that did not contain calcium carbonate but did include many angular, silt-sized inclusions of quartz and dark mica derived from igneous and metamorphic rocks (Figure 1). The clay used to manufacture the ceramics may have been procured from deposits of wind-blown silt that is abundant in northwest China, including around Xi’an where the Terracotta Army is located. The clay paste of the terracotta warriors was prepared by the addition of sand (referred to as temper), which helps control shrinkage and improves resistance to thermal shock. Bricks lining the floor of a pit where warriors are located and rammed-earth samples from another pit were also analyzed. They seemed to have been fashioned from untempered clay. Sand temper could have been added to control the plasticity or “stickiness” of the fine clay and make it more suitable for shaping. The composition of the sand also indicated that it was collected in a loose form, rather than being produced by crushing sandstone. The possible source might have been alluvial sand found in the region.

Figure 1 Thin-section photomicrographs of petrographic fabric groups and specific features detected within ceramic artefacts. A) Sand-tempered terracotta warrior statue; B) sand-tempered terracotta acrobat fragments; C) sand-and-plant-tempered core sample from bronze waterfowl; D) untempered silty brick sample; E) dark clay-rich plastic inclusion that may indicate intentional clay mixing; F) light-colored plastic inclusions in sample that may indicate the intentional mixing with the material in the previous image; G) granite rock fragment within sand temper; H) phyllite metamorphic rock fragment within sand temper. Image width = 0.5 mm, except G and H where the width = 0.25 mm. Images taken under crossed polars, except C and F, which were taken in polarized light.

The firing technology used on the statues has been debated extensively. Were they simply left to dry, fired openly such as in a bonfire, or fired in an enclosed structure such as a kiln? The presence of birefringence in the clay matrix of the samples suggests that they were not subjected to a sustained temperature above 850°C. Common clay minerals lose their crystalline structure at temperatures higher than this and would not be birefringent. Firing probably took place in a kiln-like structure due to the slow rate of temperature increase that would have been required to drive water from the thick (up to 10 cm) walls of the statues without catastrophic failure, as well as the sustained high temperature needed to harden them throughout. This could not have been controlled in an open fire or by air-drying.

The uniformity of the specimens suggests that the raw materials were obtained from a single source. A dedicated department responsible for the supply of clay would lead to less variability in composition than if this was left to individual production units. Such centralization would also help ensure a constant supply of large quantities of raw material that would have been required to produce over 7,000 statues in less than 40 years. Additional evidence supports the theory that the clay was then distributed to various ceramic workshops.

Quinn et al. have answered many important questions about how the Terracotta Army was created. They also pointed out that this surely would have required a high degree of organization on many levels. This characteristic may have laid the foundations for imperial China!