Impact statement

This large population-based, cross-sectional study conducted in China offers critical insights into the correlation between childhood trauma (CT) and the self-reported prevalence of psychiatric disorders among young adults. It reveals that individuals with a history of CT are at a heightened risk of experiencing serious and persistent psychiatric disorders and symptoms, necessitating a targeted approach to mental health support. The research also emphasizes the role of demographic factors as potential risk indicators, suggesting the importance of considering these variables when designing interventions. The implications of these findings extend to the need for public health and academic sectors to collaboratively develop strategies aimed at improving mental health outcomes and overall quality of life for youth, with a particular focus on those who have experienced CT. Additionally, the study underscores the importance of an interdisciplinary approach, and the potential for future longitudinal research to further our understanding of the long-term effects of CT on mental health. This underscores the urgency for policy-makers and healthcare providers to prioritize and invest in comprehensive mental health services, especially for high-risk groups.

Introduction

Childhood trauma (CT), or childhood maltreatment refers to all forms of emotional and physical mistreatment, sexual abuse (SA), neglect and other traumatic experiences during childhood (World Health Organization, 2014), and has been internationally recognized as a serious and urgent public health problem. Moreover, exposure to CT has profound and lasting effects on an individual’s mental health and well-being, in terms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), personality disorders, substance use disorders (SUDs), sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and even suicidal behaviors (Zatti et al., Reference Zatti, Rosa, Barros, Valdivia, Calegaro, Freitas, Ceresér, Rocha, Bastos and Schuch2017; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Fairchild, Hammerton, Murray, Santos, Tovo Rodrigues, Munhoz, Barros, Matijasevich and Halligan2022). Thus, it is vital to investigate the lasting effects of CT and related risk factors, and apply early screening and intervention for young adults with CT experiences.

CT and childhood maltreatment raise significant mental health concerns on an international level. Specific prevalence rates can vary widely between countries and regions due to differences in culture, socioeconomic conditions and the availability and quality of data. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Massullo et al., Reference Massullo, De Rossi, Carbone, Imperatori, Ardito, Adenzato and Farina2023) suggest the prevalence of CT among young adults’ ranges from 13.4% to 64.7% depending on the country, such as 13.4% in Germany, 34.3% in Brazil, and 64.7% in China (Witt et al., Reference Witt, Brown, Plener, Brähler and Fegert2017; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Feng, Qin, Wang, Wu, Cai, Lan and Yang2018; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Fairchild, Hammerton, Murray, Santos, Tovo Rodrigues, Munhoz, Barros, Matijasevich and Halligan2022). There is a consistently high prevalence of child maltreatment in the East Asia and Pacific regions. Between one in 10 children experience physical abuse (PA) and 30.3% of children suffer from abuse according to a systematic review of data from the East Asia and Pacific regions (Fry et al., Reference Fry, McCoy and Swales2012). According to another report, the individual prevalence rates for PA, emotional abuse (EA), SA and neglect in China are 26.6%, 19.6%, 8.7% and 26.0%, respectively (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Fry, Ji, Finkelhor, Chen, Lannen and Dunne2015). It is important to note that these figures are estimated based on outdated data and that the actual prevalence may be higher, as well as due to other common factors such as underreporting. Regardless, these high rates highlight the extent of CT and underscore the urgent need for interventions and support systems to address this issue, particularly in China.

Exposure to CT has been shown to cause deleterious physical and psychological outcomes that can persist into adulthood (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Fairchild, Hammerton, Murray, Santos, Tovo Rodrigues, Munhoz, Barros, Matijasevich and Halligan2022). Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported that young adults exposed to any form of CT are at an increased risk of chronic psychological disorders (Read et al., Reference Read, van Os, Morrison and Ross2005; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Schairer, Dellor and Grella2010; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos2012; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton, Jones and Dunne2017; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021; Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Yoo, Kim, Ryu, Lee, Kim and Kim2021). For example, a meta-analysis using a longitudinal cohort study found that experiencing CT results in more than three times the odds of developing a psychiatric disorder (OR = 3.11, 95% CI: 1.36–7.14 McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021). Another cohort cross sectional and case controlled meta-analysis found significant associations between CT and depressive disorders, suicide attempts, SUDs and STIs (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos2012). Furthermore, several studies also reported that exposure to CT could increase the risk of depression, anxiety, PTSD, psychosis, SUDs, attachment disorder and suicidal behaviors (Read et al., Reference Read, van Os, Morrison and Ross2005; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Schairer, Dellor and Grella2010; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton, Jones and Dunne2017; Park et al., Reference Park, Park, Yoo, Kim, Ryu, Lee, Kim and Kim2021; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Fairchild, Hammerton, Murray, Santos, Tovo Rodrigues, Munhoz, Barros, Matijasevich and Halligan2022). Neurobiology studies of CT further suggested experiences of CT would cause long-term neurobiological changes that impact individual development brain function (Hesdorffer et al., Reference Hesdorffer, Rauch and Tamminga2009), such as brain circuits, hormonal systems and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, which affects the ability to modulate behavioral and cognitive responses to subsequent stress (Nemeroff, Reference Nemeroff2004; Assogna et al., Reference Assogna, Piras and Spalletta2020). Considering the serious mental health consequences of CT, it is crucial to investigate the risk factors of youth who have had CT experiences to implement effective measures to improve their quality of life and well-being.

Several researches have explored the risk factors (i.e., psychosocial, environmental and genetic) of psychiatric disorders among CT survivors. Systematic reviews reported that sex, race, ethnicity, educational level, lower social status could be moderators for CT and psychopathology (Jaffee and Maikovich-Fong, Reference Jaffee and Maikovich-Fong2011; Petruccelli et al., Reference Petruccelli, Davis and Berman2019; Kisely et al., Reference Kisely, Strathearn and Najman2020). Social support, self-esteem, self-reliance and lifestyle factor are associated with psychiatric disorders among those who have experienced CT (Horan and Widom, Reference Horan and Widom2015; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Murat Baldwin, Wong, Obsuth, Meinck and Murray2023). For instance, females report more CT than males and are more likely to have negative health outcomes. A non-white race/ethnicity, lower educational level and lower socioeconomic status have all been significantly associated with CT experiences (Petruccelli et al., Reference Petruccelli, Davis and Berman2019). Furthermore, tobacco use and increased alcohol consumption also have shown associations with CT in both adjusted and unadjusted models (Petruccelli et al., Reference Petruccelli, Davis and Berman2019; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Murat Baldwin, Wong, Obsuth, Meinck and Murray2023).

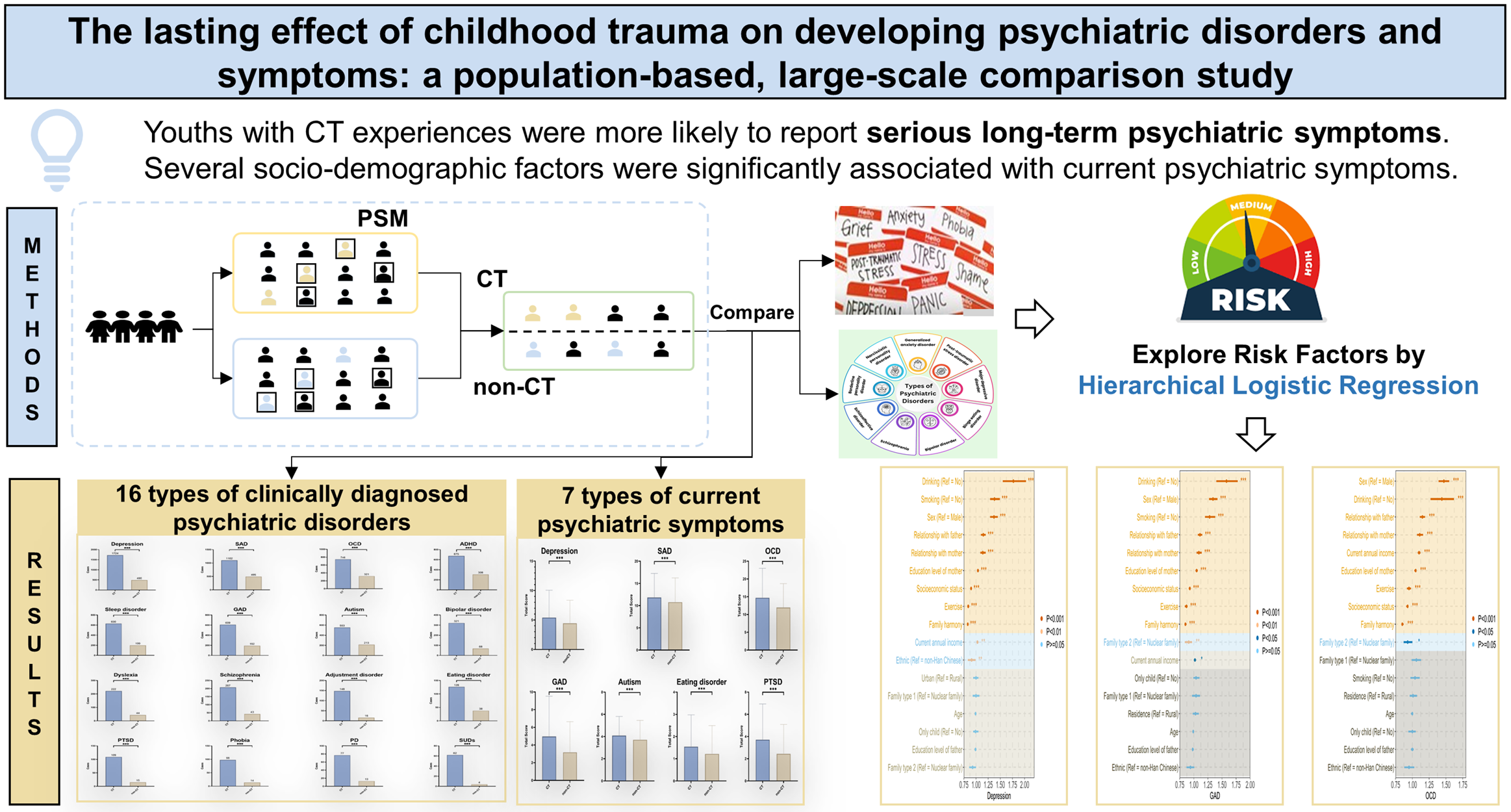

However, few studies utilized a large sample size and few studies control for confounding factors (i.e., some sociodemographic factors) when exploring the effects of CT among young adults, especially the combination of psychiatric disorders and current psychiatric symptoms. Therefore, this study conducted a large-scale survey covering more than 110,000 Chinese youth to investigate the long-term psychological consequences of CT as well as risk factors after controlling for confounding sociodemographic factors. The aims of this study were 1) to estimate the prevalence of CT among Chinese young adults; 2) to investigate 16 self-reported psychiatric disorders in CT youth compared with non-CT youth after controlling for confounding factors; and 3) to examine the risk factors for seven types of psychiatric symptoms among youth with CT experiences. The hypotheses of this study were 1) after controlling for confounding factors, there would be significant differences of prevalence and severity of psychiatric disorders between CT and non-CT groups; 2) several sociodemographic factors, such as age, sex, residence and current annual family income, are expected to demonstrate significant associations with an elevated risk of current psychiatric symptoms among youth with CT experiences.

Methods

Study design and settings

This large-scale cross-sectional study was undertaken by Jilin University, China, from October to November 2021, covering 63 colleges and universities in Jilin province. The study design followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline (Von Elm et al., Reference Von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2007), a convenience sampling method was used in this study. The quick response code (QR code) was linked to the web-based self-administered questionnaire and this was distributed to participants online via on the official accounts of each college and university. The inclusion criteria were: 1) currently enrolled in colleges and universities in Jilin province; 2) aged 15 years and older; 3) possess a satisfactory comprehension of the assessment content and the simplified Chinese language. This study received ethical approval from Jilin University (N020210929 [11 October 2021]) in accordance with the principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its 2013 amendments (World Medical Association, 2013). Electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants.

A total of 117,769 students participated and completed the questionnaire in this survey during the data collection period. Figure 1 provides an overview of the participant screening and exclusion process. Out of the 117,769 individuals, a total of 21,551 participants were excluded, including those who failed attention checks (21,541) and 10 with suspected abnormal data according to unreasonable age, height and weight values. This resulted in a final sample of 96,218 participants, representing a response rate of approximately 81.7%. In terms of questionnaire design, the relevant assessment scales were administered and the basic sociodemographic characteristics were collected, including age, sex at birth, residence, current annual family income, socioeconomic status, only child status, ethnicity, smoking status, consuming alcohol and exercise.

Figure 1. Flowchart of recruitment procedures.

Abbreviations: CT, childhood trauma; CTQ-SF, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form; EA, emotional abuse; EN, emotional neglect; PA, physical abuse; PN, physical neglect; SA, sexual abuse.

Measurements

Childhood trauma

CT experiences were measured using the Chinese version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF), a self-report inventory consisting of 28 items rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true; Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge, Ahluvalia, Stokes, Handelsman, Medrano and Desmond2003). The CTQ-SF is designed to assess five categories of CT, EA, emotional neglect (EN), PA, physical neglect (PN) and SA, identified by moderate to severe cutoff scores in each subscale. Specifically, cutoff scores of 13 or higher for EA, 15 or higher for EN, 10 or higher for PA, 10 or higher for PN and 8 or higher for SA (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Kirschbaum, Wankerl, Stauch, Stalder, Steudte-Schmiedgen, Muehlhan and Miller2018). Individuals with at least one type of abuse identified were divided into the CT group. The modified Chinese version of CTQ-SF has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79 among Chinese participants (He et al., Reference He, Zhong, Gao, Xiong and Yao2019).

Assessment of 16 psychiatric disorders

The 16 psychiatric disorders were to be diagnosed by psychiatrists, however, the psychiatric disorder was self-reported by the participants. Participants were asked the question, “Have you ever been diagnosed by a psychiatrist with any of the following psychiatric disorders? (You can select multiple).” With choices including: (1) autism; (2) attention-deficit hyperactivity-disorder (ADHD); (3) depression; (4) bipolar disorder; (5) generalized anxiety disorder (GAD); (6) obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD); (7) schizophrenia; (8) phobia; (9) PTSD; (10) panic disorder (PD); (11) SUDs; (12) learning disabilities/dyslexia; (13) sleep disorders; (14) adjustment disorders; (15) eating disorders; (16) social anxiety disorder (SAD); (17) other (fill in the blank); (18) none of the above.

Assessment of seven types of current psychiatric symptoms

The seven current psychiatric symptoms included: depression, GAD, eating disorders, OCD, autism, SAD and PTSD, and were measured by their respective self-report scales. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), has nine items, assessing depressive symptoms over the last 2 weeks using a cutoff value of 5 (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001). A higher score on this scale indicates a higher level of depressive symptoms. Participants choose the questions that have bothered them over the past 2 weeks, with responses ranging from one (not at all) to three (nearly every day). It has demonstrated good performance in the Chinese population, with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 86% (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Bian, Zhao, Li, Wang, Du, Zhang, Zhou and Zhao2014) The Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale assesses anxiety (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006), with a cutoff point of 5 to classify respondents as having high (5 or higher) or low (less than 5) levels. This scale has demonstrated excellent sensitivity and specificity (>85%) in its application within China (He et al., Reference He, Li, Qian, Cui and Wu2010). The Sick Control One Fat Food (SCOFF) questionnaire measures eating disorders, and a score of 2 or higher indicates a likely positive case (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Reid and Lacey1999). The scale exhibits a sensitivity of 97.7% and a specificity of 94.4% (Kutz et al., Reference Kutz, Marsh, Gunderson, Maguen and Masheb2020). The Dimensional Obsessive–Compulsive Scale-short Form (DOCS-SF) evaluates OCD providing a brief (five-item) measure of OCD symptoms and has a suggested cutoff score of 16 to diagnose negative or positive behaviors, while demonstrating a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 94% (Eilertsen et al., Reference Eilertsen, Hansen, Kvale, Abramowitz, Holm and Solem2017). The 10-item Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ-10) assesses autism symptoms through a specialist evaluation. A cutoff point greater than or equal to 6 indicates the presence of autism symptoms (Allison et al., Reference Allison, Auyeung and Baron-Cohen2012), and it has a sensitivity of 74% and a specificity of 85% (Leung et al., Reference Leung, Leung, Chan and Leung2023). The subscale of self-consciousness measured SAD, rates higher scores as associated with worse symptoms (Fenigstein et al., Reference Fenigstein, Scheier and Buss1975). The Chinese version of the subscale of self-consciousness has a reliable internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79 (Shek, Reference Shek1994). The Trauma Screening Questionnaire (TSQ, Chinese version) identifies the severity of potential PTSD, adapted from the PTSD Symptom Scale – Self-Report Version (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Riggs, Dancu and Rothbaum1993), which has been utilized in various samples across countries (Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge, Ahluvalia, Stokes, Handelsman, Medrano and Desmond2003; Walters et al., Reference Walters, Bisson and Shepherd2007; Wu, Reference Wu2014; Knipscheer et al., Reference Knipscheer, Sleijpen, Frank, de Graaf, Kleber, Ten Have and Dückers2020). It consists of five re-experiencing items (e.g., “upsetting dreams about the event”) and five arousal items (e.g., “difficulty falling or staying asleep”). Participants are asked to answer the question of whether they had experienced these items before, using “Yes” (scored 1) or “No” (scored 0). Six or more positive responses indicated that the respondent was at risk of PTSD. It shows good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.93) in Chinese university students (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Leung, Wong, Yu, Luk, Cheng, Wong, Wong, Lui and Ngan2019).

Collection of sociodemographic variables

Our study collected sociodemographic variables through self-report measures, including current annual family income and socioeconomic status. To assess the variable “current annual family income,” participants were asked the following question: “What is your household’s current annual income?” This question sought to determine the average amount available for expenditure and savings per person in their household. To assess the variable “socioeconomic status,” participants provided self-reported data, rating their perceived socioeconomic status using the Chinese version of the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Socioeconomic Status (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Epel, Castellazzo and Ickovics2000; Xiaona and Xiaoping, Reference Xiaona and Xiaoping2018). This scale involves participants selecting a number from 0 to 10, using a ladder figure, with higher numbers indicating a higher perceived socioeconomic status.

Statistical analysis

Propensity score matching

The propensity score matching (PSM) method was utilized to balance the potential confounding factors between the CT and non-CT groups. Propensity scores were calculated by a logistic regression model, minimizing the influence caused by a set of unmatched sociodemographic characteristics, including sex, age, ethnicity, residence, only-child (yes or no), current annual family income and socioeconomic status. Based on the propensity scores, participants were paired 1:1 using the nearest neighbor method, with a caliper width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score (Austin, Reference Austin2011). In addition, the standardized mean difference (SMD) was computed to assess balance after PSM, where a SMD less than 0.1 indicated a substantial balance (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Kim, Lonjon and Zhu2019). Furthermore, the independent sample t-test and chi-squared test were performed before and after the PSM procedure, using the aforementioned sociodemographic characteristics among the two groups, CT and non-CT. The PSM procedure was conducted with the “MatchIt” package in R. After balancing the confounding factors, the prevalences of self-reported psychiatric disorders were compared with the chi-squared test between the CT and non-CT groups, while the total score of current psychiatric symptoms were compared with the independent sample t-test between the two groups. All analysis procedures were performed with R software, with the significance level (α) preset at 0.05 for all two-tailed tests.

Hierarchical regression model

In order to identify risk factors of current psychiatric symptoms from sociodemographic characteristics and family-related factors in the youth with CT experiences, a hierarchical regression procedure was conducted by assigning the above covariates to different blocks. The hierarchical logistic regression method was selected for the six types of psychiatric symptoms, which corresponds with the scales used in this study that had definite cutoff values, and the psychiatric symptoms were taken as the response variable. For SAD, without a clear cutoff value, the hierarchical linear regression method was used to explore the risk factors. Both the hierarchical logistic regression and the hierarchical linear regression were performed with SPSS version 26. All null hypothesis significance testing was conducted at the two-tailed level with significance of 0.05.

Results

Control for confounding factors

Following the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 96,218 participants were enrolled, including 68,547 in non-CT group and 27,671 in CT group. The PSM procedure was then performed to balance the distribution of all baseline covariates (i.e., age, sex, residence, current annual income, socioeconomic status, only-child status, ethnicity) between the CT and non-CT groups, ensuring the accuracy and robustness of subsequent analysis results. Summary statistics for the baseline characteristics of CT and non-CT groups before and after PSM are shown in Table 1. After matching, SMDs for all characteristics were <0.10, indicating no significant difference between these two groups. After balancing confounding factors, the CT and non-CT groups comprised 27,671 samples, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of CT and non-CT groups, before and after PSM (N total = 96,218)

Note: The numbers in parentheses denote “% of the sample for the corresponding subpopulation (CT and non-CT).” P 1 represents P-value of t-test or chi-squared test comparing non-CT to CT samples before PSM. P 2 represents P-value of t-test or chi-squared test comparing non-CT to CT samples after PSM.

Abbreviations: CT, childhood trauma; PSM, propensity score matching; SD, standard deviation; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Comparison of self-reported psychiatric disorders

As reported in Table 2, there was a significant higher prevalence of the 16 types of self-reported psychiatric disorders in youth with CT experiences than those without CT experiences (Table 2; P < 0.001). Figure 2 demonstrates the differences of participants with the 16 types of self-reported psychiatric disorders between the CT and non-CT groups.

Table 2. Differences between CT and non-CT groups in self-reported psychiatric disorders

Note: χ2 tests for between-category differences.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder; CT, childhood trauma; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PD, panic disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder; SUDs, substance use disorders.

Figure 2. Comparison the number of cases with 16 types of clinically diagnosed psychiatric disorders between the CT and non-CT groups.

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder; CT, childhood trauma; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PD, panic disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder; SUDs, substance use disorders. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Comparison of current psychiatric symptoms

Table 3 shows that the CT group reported a significantly worse current symptom status regarding seven types of psychiatric symptoms than the non-CT groups (P < 0.001). Figure 3 depicts the comparison of total scores in the seven types of current psychiatric symptoms between the CT and non-CT groups.

Table 3. Differences between CT and non-CT groups and current psychiatric symptoms

Note: The numbers out and in parentheses, respectively, denote “mean and standard deviation of the sample for the corresponding subpopulation (CT and non-CT).” Mean and standard deviation are provided for the scores on scales of current psychiatric symptoms above.

Abbreviations: CT, childhood trauma; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder.

Figure 3. Comparison of total scores of seven current psychiatric symptoms in the CT and non-CT groups.

Abbreviations: CT, childhood trauma; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder.

Risk factors of current psychiatric symptoms

Table 4 presents the summary results of all hierarchical regression models, and total results are presented in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material. The overall outcomes of forest plot are presented in Figure 4.

Table 4. Exploring risk factors for current psychiatric symptoms by hierarchical regression analysis among the CT group

Note: Hierarchical logistic regression was performed to find risk factors for six diseases: Depression, GAD, OCD, autism, eating disorder and PTSD according to the cutoff values of the corresponding scales. Since the scale of SAD has no definite cutoff value, hierarchical logistic regression cannot be performed, so hierarchical linear regression is adopted here. This table only presents the results of the second layer of regression. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Bold values refer to significant associations between the independent and dependent variables at α = 0.001.

Abbreviations: b, standardized regression coefficient; CI, confidence intervals; CT, childhood trauma; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; OR, odds ratios; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder.

Figure 4. Forest plots for the results of hierarchical logistic regression.

Abbreviations: GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder; Family type 1: More than three generation; Family type 2: Others.

In the final hierarchical regressions, family-related factors in the CT groups (i.e., family type, relationship with father, relationship with mother, family harmony, education level of mother, education level of father) improved the goodness of fit of the sociodemographic model. Table 4 illustrates that the sociodemographic characteristics, including sex, socioeconomic status, smoking, alcohol consumption, exercise, as well as family factors, specifically, relationship with father, relationship with mother, family harmony and father’s education level, were significantly associated with the prevalence of current psychiatric symptoms among the CT population. Females were more likely to display current psychiatric symptoms, other than autism (i.e., depression, GAD, OCD, eating disorders, PTSD, SAD), particularly eating disorders (OR = 2.09, 95% CI = 1.98–2.21, P < 0.001). Participants with a higher socioeconomic status were also less prone to current psychiatric symptoms. Among the lifestyle variables, smoking status, consumption of alcohol and lack of exercise were established as risk factors for these current psychiatric symptoms in CT populations. In terms of family variables, both education level of the father and a poor relationship with parents were significantly associated with current psychiatric symptoms. Family harmony was a protective factor for six types of current psychiatric symptoms outside of autism (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.02–1.05, P < 0.001).

Discussion

This large cross-sectional study explored the lasting effects of CT by combining the self-reported psychiatric disorders and current psychiatric symptoms among Chinese young adults. Moreover, this study investigated the risk factors of current psychiatric symptoms among those with experiences of CT. The results showed that the prevalence of both self-reported psychiatric disorders and current psychiatric symptoms were significantly higher in youth with CT experiences. Furthermore, several sociodemographic factors (i.e., females, family disharmony and low socioeconomic status, lifestyle factors) were significantly associated with current psychiatric symptoms. These findings are crucial to better understand the effect of CT and ply appropriate interventions.

In this study, the prevalence of CT was 28.76% (95% CI: 28.47–29.04%) among Chinese young adults. This figure is lower than Brazil (34.3%; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Fairchild, Hammerton, Murray, Santos, Tovo Rodrigues, Munhoz, Barros, Matijasevich and Halligan2022) and the meta-analysis from China (64.7%; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Feng, Qin, Wang, Wu, Cai, Lan and Yang2018), but higher than in Germany (13.4%; Witt et al., Reference Witt, Brown, Plener, Brähler and Fegert2017). In Brazil, the prospective birth cohort study reported that 1,154 (34.3%) of 3,367 children at age 11 years had been exposed to trauma (including CT and other traumas; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Fairchild, Hammerton, Murray, Santos, Tovo Rodrigues, Munhoz, Barros, Matijasevich and Halligan2022). In China, based on a meta-analysis of nine articles, the pooled prevalence of CT was 64.7% (95% CI: 52.3%–75.6%) among Chinese college students (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Feng, Qin, Wang, Wu, Cai, Lan and Yang2018). A large review of a series of meta-analyses, including 244 publications and 551 prevalence rates reported a prevalence of 127/1,000 for SA, 226/1000 for PA and 363/1,000 for EA (Stoltenborgh et al., Reference Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Alink and van IJzendoorn2015). This study focused on additional experiences of CT among young adults, including EA, EN, PA, PN and SA. Due to the lack of comprehensive studies, research exploring broader adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), childhood maltreatment and early life adversity (Boullier and Blair, Reference Boullier and Blair2018) can provide additional insight. These experiences would encompass any adverse or stressful experiences encountered during childhood, including maltreatment and other forms of adversity such as poverty, parental separation or divorce, chronic illness, natural disasters or exposure to community violence (Merrick et al., Reference Merrick, Ford, Ports and Guinn2018; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wu, Liu, Li, Hu and Li2021; Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Racine, Vaillancourt, Korczak, Hewitt, Pador, Park, McArthur, Holy and Neville2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of 206 studies reported the pooled prevalence of ACEs in young adults to be: 39.9% (95% CI: 29.8–49.2) experienced no ACE and 22.4% of youth did (95% CI: 14.1–30.6), everyone ACE for half a million adults (Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Racine, Vaillancourt, Korczak, Hewitt, Pador, Park, McArthur, Holy and Neville2023), while another meta-analysis found the lifetime prevalence of four or more ACEs was 53.9% (95% CI: 45.9–61.7) among unhoused individuals (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wu, Liu, Li, Hu and Li2021), suggesting a strong link to poverty. In 2011–2014, the prevalence of ACEs in a sample of 214,157 adult respondents, using eight categories of maltreatment, across 23 states, was 61.55% (Merrick et al., Reference Merrick, Ford, Ports and Guinn2018). However, considering the various definitions of ACEs, CT and childhood maltreatment, the pooled prevalence of these experiences should be compared with uniform definitions and standards, especially in different countries.

Although the prevalence of CT found in this study was different from the several studies mentioned, this is due to different assessments of CT (CTQ VS. questions), ages of participants (young adults vs. children) and different cultural contexts across the studies. Additionally, individuals who experience CT may be reluctant to discuss their past experiences, leading to a lower reported prevalences of the condition (Pasupathi et al., Reference Pasupathi, McLean and Weeks2009). Besides, in Jilin Province, which is primarily an agricultural region in China, some individuals may not be aware that they have experienced CT. In China’s cultural context, these youth might perceive occasional parental discipline as a normal occurrence. This lack of awareness may contribute to a certain degree of reduced report rates for CT.

The results showed that after controlling for confounding factors, the prevalence rates of self-reported psychiatric disorders and total scores of current psychiatric symptoms were significantly higher among the CT group. These results further demonstrated the sustained damage of CT upon mental health among young adults, which is consistent with previous researches. For example, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate a significant association between childhood exposures (EA, PA and trauma exposure) and adult psychiatric disorders (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021), between CT and lifetime suicide attempts risk (Zatti et al., Reference Zatti, Rosa, Barros, Valdivia, Calegaro, Freitas, Ceresér, Rocha, Bastos and Schuch2017), between CT and anxiety, depression and substance disorders (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Kilmartin, Meagher, Cannon, Healy and Clarke2022), as well as sleep disorders, PTSD, ADHD, SUDs and other psychiatric disorders (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Murad, Paras, Colbenson, Sattler, Goranson, Elamin, Seime, Shinozaki, Prokop and Zirakzadeh2010; Mironova et al., Reference Mironova, Rhodes, Bethell, Tonmyr, Boyle, Wekerle, Goodman and Leslie2011; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos2012; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer, Read, van Os and Bentall2012; Lindert et al., Reference Lindert, von Ehrenstein, Grashow, Gal, Braehler and Weisskopf2014; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton, Jones and Dunne2017; Thabet, Reference Thabet2017). Notably, prospective cohort studies also have found that after adjusting for childhood risk factors, cumulative CT exposure is still related to higher rates of adult psychiatric outcomes, including anxiety, depression and SUDs (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Hinesley, Chan, Aberg, Fairbank, van den Oord and Costello2018; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Fairchild, Hammerton, Murray, Santos, Tovo Rodrigues, Munhoz, Barros, Matijasevich and Halligan2022). Our results support the associations between CT experiences and psychiatric disorders to some extent. The extant literature has suggested exposure to CT would cause neurological, physiological and psychological disruptions (Varese et al., Reference Varese, Smeets, Drukker, Lieverse, Lataster, Viechtbauer, Read, van Os and Bentall2012; Massullo et al., Reference Massullo, De Rossi, Carbone, Imperatori, Ardito, Adenzato and Farina2023). Experiences with CT could induce neurodevelopmental changes, such as dysregulation of the functioning of HPA, which plays a central role in the body’s response to stress (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Cannon, Chambers, Conroy, Coughlan, Dodd, Healy, O’Donnell and Clarke2021). Several studies have found that adults with a history of childhood abuse demonstrate persistent sensitization of the pituitary–adrenal and autonomic stress response, which might increase the risk of psychiatric disorders among CT survivors (Lindert et al., Reference Lindert, von Ehrenstein, Grashow, Gal, Braehler and Weisskopf2014). Secondly, according to psychological theories, CT experiences might affect a child’s cognitive schema of themselves, others and the world, which leaves them vulnerable to negative beliefs (Dannlowski et al., Reference Dannlowski, Stuhrmann, Beutelmann, Zwanzger, Lenzen, Grotegerd, Domschke, Hohoff, Ohrmann, Bauer, Lindner, Postert, Konrad, Arolt, Heindel, Suslow and Kugel2012). These negative cognitions may affect the individual’s later susceptibility to psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, PTSD and OCD, as well as sensitivity to rejection and abandonment, unstable relationships and difficulty with trust (Lindert et al., Reference Lindert, von Ehrenstein, Grashow, Gal, Braehler and Weisskopf2014). More seriously, CT has been found to affect the young person’s quality of life, and increase the risk of suicidal behaviors (Lindert et al., Reference Lindert, von Ehrenstein, Grashow, Gal, Braehler and Weisskopf2014; Zatti et al., Reference Zatti, Rosa, Barros, Valdivia, Calegaro, Freitas, Ceresér, Rocha, Bastos and Schuch2017). Several studies have found that young adults who report a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts have experienced SA and PA (Hesdorffer et al., Reference Hesdorffer, Rauch and Tamminga2009). Considering the devastating effect of CT experiences on young adults, the mental health status of these individuals requires further attention and effective strategies are required to improve their quality of life.

According to these results, females with CT were more likely to report current psychiatric symptoms, which is consistent with previous studies (DeWit et al., Reference DeWit, Chandler-Coutts, Offord, King, McDougall, Specht and Stewart2005; Afifi et al., Reference Enns, Cox, Asmundson, Stein and Sareen2008; Tolin and Foa, Reference Tolin and Foa2008; Sweeney et al., Reference Sweeney, Air, Zannettino, Shah and Galletly2015; Pruessner et al., Reference Pruessner, King, Vracotas, Abadi, Iyer, Malla, Shah and Joober2019; Tsapenko, Reference Tsapenko2021; Bhattacharya and Sharan, Reference Bhattacharya and Sharan2022). Particularly, a near-term study suggested females with ACEs (e.g., SA, domestic violence) appeared to have more complex patterns of social and emotional difficulties, incurring mental health issues across the lifespan (Haahr-Pedersen et al., Reference Haahr-Pedersen, Perera, Hyland, Vallières, Murphy, Hansen, Spitz, Hansen and Cloitre2020). Several suggestions might explain these results. First, compared to males, females appear more vulnerable to acute emotional responses (Olff et al., Reference Olff, Langeland, Draijer and Gersons2007; e.g., intense fear, helplessness, horror, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, panic and anxiety) as well as acute dissociative responses, they are more likely to fall into rumination. These female youth would build a negative cognitive schema of repetitively and passively ruminating and reflecting on symptoms of distress, which increased the risk of psychiatric symptoms and disorders developing (Hesdorffer et al., Reference Hesdorffer, Rauch and Tamminga2009). Moreover, sex differences in coping styles exist when it comes to trauma, with males inclined to exhibit more problem-focused reactions to CT experiences, while females present with emotion-focused coping strategies (Sigurdardottir et al., Reference Sigurdardottir, Halldorsdottir and Bender2014). Furthermore, sex hormones particularly progesterone (female dominant), might facilitate the development of anxiety and PTSD, especially as most youths experiencing puberty during the episode(s) of CT. All these factors could potentially explain why females were more likely to report current psychiatric symptoms when they have experienced CT.

In accordance with previous studies (Trinidad et al., Reference Trinidad, Chou, Unger, Anderson Johnson and Li2003; Tylka and Kroon Van Diest, Reference Tylka and Kroon Van Diest2015; Thabet, Reference Thabet2017), young adults with CT experiences who were from harmonious family environments were less likely to suffer from current psychiatric symptoms. Substantial studies have found the important role of family harmony in a child’s development, particularly in the Chinese cultural context (Alink et al., Reference Alink, Cicchetti, Kim and Rogosch2009; Nursalam et al., Reference Nursalam, Ni Ketut Alit and Rista2009; Balistreri and Alvira-Hammond, Reference Balistreri and Alvira-Hammond2016; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Ma, Yu, Ye, Li, Lu and Wang2021). The perception of support and encouragement from family and the high levels of intimacy are particularly important for improving self-confidence and self-esteem and reducing negative emotions. For example, Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Ma, Yu, Ye, Li, Lu and Wang2021) explored the mediating roles of family functioning between CT and general distress, reporting that good family functioning could predict better emotional states. Additionally, studies also discovered that higher family social support brings higher self-esteem and more optimistic views, which is conducive to coping with problems positively. Furthermore, the study found that higher socioeconomic status is related to a lower risk of current psychiatric symptoms. The higher socioeconomic status usually is related to the higher educational levels of parents (Bradley and Corwyn, Reference Bradley and Corwyn2002), which is associated with higher empathy and providing familial support to their children when they experience CT. Higher socioeconomic status also comes with the resources to pay for professional help, given the high treatment fee in China and shortage of practitioners. All these factors could help young adults cope better with CT experiences and reduce the risk of psychiatric disorders and symptoms.

Apart from the above factors, lifestyle factors, including exercise, smoking status and alcohol consumption, are further associated with current psychiatric symptoms among those who have experienced CT. The advantage of exercise for improving mental health status has been well established, such as antidepressant effects and anxiolytic neurobiological effects (e.g., improved HPA axis functioning, increased monoamine neurotransmission), which are beneficial for adolescents to develop life skills (e.g., initiative, teamwork, self-control). Moreover, exercise provides a distraction from stressors, keeping individuals away from constant worry thereby reducing depression and anxiety (Salmon, Reference Salmon2001; Motta et al., Reference Motta, McWilliams, Schwartz and Cavera2012; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Moyen, Lawson, Rappaport, Yousif, Fleurent-Grégoire, Lalonde-Bester, Brazeau and Chevalier2023). Smoking status and alcohol consumption have been suggested as harmful to the mental health of younger adults (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Sherritt and Knight2005; Giannakopoulos et al., Reference Giannakopoulos, Tzavara, Dimitrakaki, Kolaitis, Rotsika and Tountas2010; Barry et al., Reference Barry, Jackson, Watkins, Goodwill and Hunte2017; Tembo et al., Reference Tembo, Burns and Kalembo2017; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Jardim, Sousa, Rosa and Jardim2019). Furthermore, youth with CT experiences would be more likely to smoke and drink as coping methods to relieve the negative effects of CT, with the associations between psychiatric symptoms, smoking or/and drinking strengthened in turn. Therefore, to improve the quality of life and mental health of youth with CT experiences, suitable lifestyle guidance should be recommended, such as more exercise, less smoking and less units of alcohol.

Research and practical implications

Recognizing the lasting effects of CT on mental health, future interventions for young adults should adopt a comprehensive and tailored approach. First, programs should offer evidence-based therapeutic interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT; Cohen and Mannarino, Reference Cohen and Mannarino2019), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Choi-Kain et al., Reference Choi-Kain, Wilks, Ilagan and Iliakis2021) and trauma-informed therapies, to address the complex interplay of trauma-based symptomology as well as additional mental health disorders. Moreover, interventions should prioritize early identification of CT and special attention should be given to at-risk children as a preventive measure to mental health issues later in life. This could involve implementing screening protocols in primary care settings, educational institutions and community organizations to identify children who may be experiencing CT. Furthermore, holistic support services should be established to address the diverse needs of young adults affected by CT later in life. This includes providing access to counseling services, psychiatric care, peer support groups and other resources aimed at promoting resilience and recovery in youths. Additionally, interventions should incorporate psychoeducation components to enhance young adults’ understanding of CT and its impact on mental health, empowering them to seek help and advocate for their needs. Collaboration between healthcare providers, educators, policymakers and community stakeholders is essential to ensure the successful implementation of these interventions. By working together, they can create a supportive and inclusive environment that promotes healing, resilience and holistic well-being for young adults affected by CT.

Limitations of the study

Although this is a large-scale study to investigate the psychiatric impact of CT experiences among more than 110,000 college students in China, several limitations should be noted. First, CT experiences and previous psychiatric disorders were trusted as reported accurately by participants in terms of if they were actually diagnosed by psychiatrists, and the self-report by participants would have caused recall bias to some extent. In addition, the comorbid diagnoses of psychiatric disorders failed to be captured in this study. Longitudinal studies should be conducted to reduce recall bias and comorbidity needs to be considered in the design measures. Furthermore, due to the study design, several important moderators such as social support, self-esteem, self-reliance were not measured. The association between CT and psychiatric disorders required thorough exploration. Due to the cross-sectional design, causality between variables and psychiatric symptoms cannot be determined. Additionally, due to the general call for participants among college students, there may be an over- or underrepresentation of those with CT experiences, as individuals may be more or less likely to enroll in the study. Moreover, appropriate psychological counseling information is not enough to help participants mitigate mental health risks when collecting data from a large sample size. In the future, a supportive school environment is required to alleviate potential mental health challenges associated with traumatic experiences and prevent these from occurring in the first place. Finally, this large-scale study was conducted in Jilin province, thus, the generalization of results should be cautious and may not apply to other areas outside of China.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this is the largest population-based, cross-sectional study that compared the status of self-reported psychiatric disorders and current psychiatric symptoms between young adults with and without CT experiences in China. The results indicated that individuals exposured to CT more likely to report serious long-term psychiatric symptoms among young adults. Several demographic factors should be considered risk factors for psychiatric symptoms among those with experiences of CT, which were being female, having a lower socioeconomic status, family disharmony, poor relationship with parents, lower father’s education level and unhealthy lifestyle factors (i.e., smoking status, consumption of alcohol and lack of exercise). The implications of these findings necessitate the development of targeted strategies by public health entities and academic institutions aimed at enhancing the mental health and overall quality of life for youth, with particular attention to those who have experienced CT.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.100.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.100.

Data availability statement

All requests should be sent to the corresponding author. Based on the scientific rigor of the proposal, the study authors will discuss all requests and decide whether data sharing is appropriate.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants and staff involved in this study.

Author contribution

Y.J. and S.X. have contributed equally to this work. Conception and design of the study: Y.W., S.X.; Critical comments: Y.W., A.W.; Data analysis and all figures: Y.J., Z.S., X.L.; Data collection: S.X.; Data quality control: S.X.; Manuscript write-up: Y.J., Z.S., J.L.; Study supervision: Y.W., S.X.

Financial support

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; Gant No. 82201708) and the Striving for the First-Class, Improving Weak Links and Highlighting Features (SIH) Key Discipline for Psychology in South China Normal University.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The ethical approval of this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of Jilin University (N020210929 [11 October 2021]), following the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its amendments in 2013. Electronic informed consent was provided by all participants, with consent that their answers could be applied to any additional analyses.

Comments

Dear Professor Judy Bass and Professor Dixon Chibanda,

We write this cover letter on behalf of all authors in support of submitting the enclosed article titled, “The lasting effect of childhood trauma on developing psychiatric symptoms: a population-based, large-scale comparison study”, for a potential publication in Global Mental Health. This is an original manuscript and it is not being considered for publication elsewhere.

This is the largest population-based, cross-sectional study to compare the status of previously clinical-diagnosed and current psychiatric disorders between younger adults with and without childhood trauma (CT) experience in China, combined with propensity score matching and hierarchical regression analyses. Results showed 27,671 participants out of 117,749 young college adults (23.5%, 95% CI=28.5-29.0%) experienced CT. Meanwhile, the results indicated that exposure to CT would more likely result in serious long-term psychiatric disorders among those with CT. In addition, socio-demographic factors, including being female, family disharmony, low socioeconomic status, and lifestyles, including exercise, smoking, and alcohol consumption were significantly associated with current psychiatric symptoms among youth with CT experiences.

We deeply appreciate your favorable consideration of our manuscript and look forward to receiving comments or editorials from reviewers and editors. We strongly believe that our results are of clinical importance, have a broad public impact, and would benefit from publication in Global Mental Health.

Sincerely yours,

Dr Yuanyuan Wang

Professor, School of Psychology, Center for Studies of Psychological Application, South China Normal University, China