Impact statement

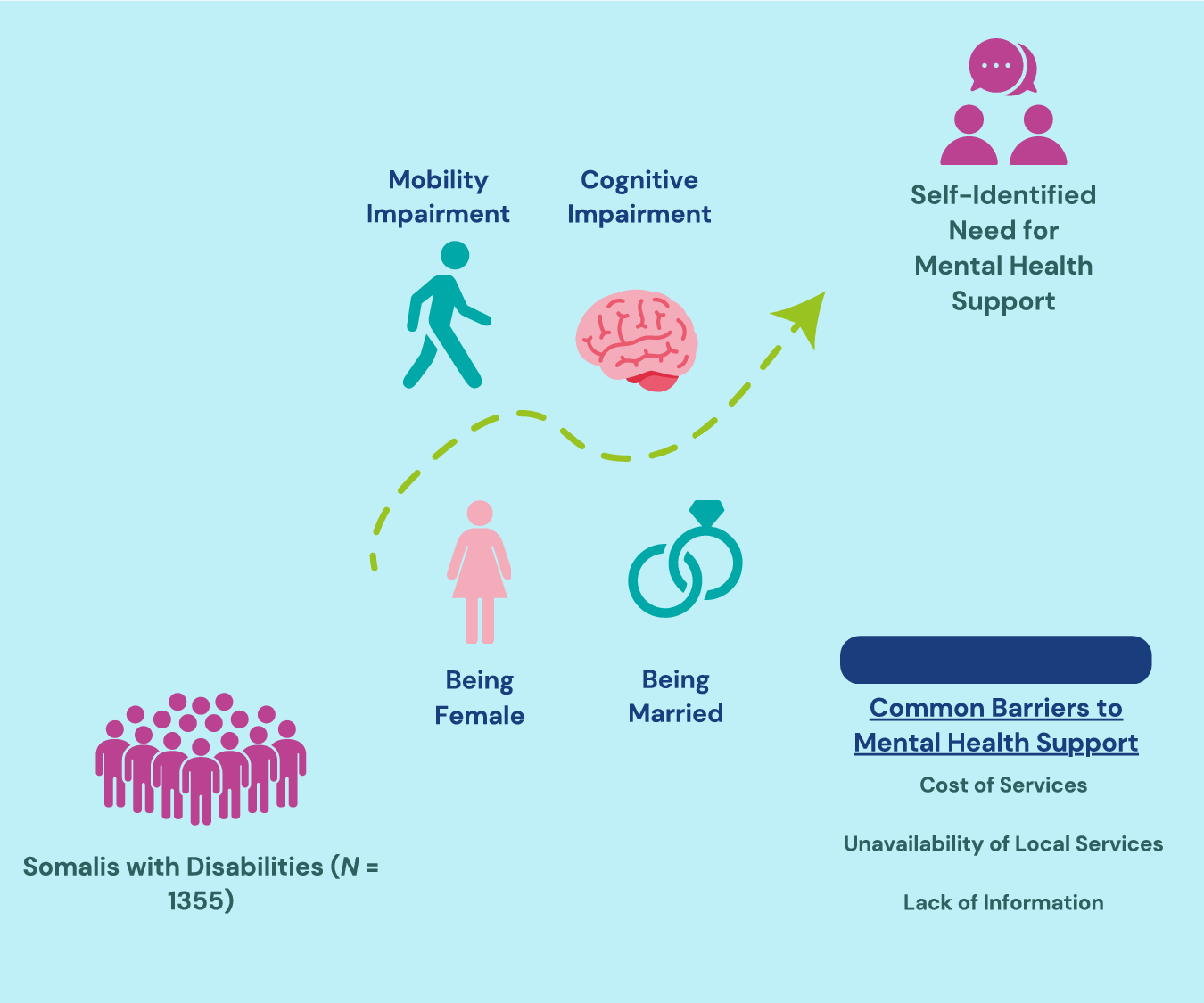

Disability and mental disorders are both pressing concerns in Global Health, particularly in low-to middle-income countries (LMICs), where the vast majority of the global population with a disability and/or mental disorder reside. Somalia stands out as an LMIC where the impact of disability and mental distress is likely especially felt, primarily due to its decades-long conflict and the resulting multitude of concurrent humanitarian crises. While previous research suggests that disability and mental distress are alarmingly common in Somalia, we are not aware of any studies that have explored both mental health- and disability-related factors in this context. We therefore aimed to determine how increasing levels of functional impairment reported across different disability domains (i.e., visual, hearing and cognition), number of concomitant disabilities, and other empirically supported variables (such as employment and sex) are associated with the likelihood of self-identifying the need for mental health support among Somalis with disabilities. In doing so, we identified certain subgroups among Somalis with disabilities who (i) may be more willing to participate in mental health and psychosocial support interventions and/or (ii) may warrant prioritisation for such intervention efforts. Additionally, we highlight the frequent barriers that Somalis with disabilities face when attempting to avail of mental health support. Findings are discussed in terms of their implications for mental health policy and mental health programming for persons with disabilities in Somalia, which is described as currently experiencing a ‘mental health crisis’.

Social media summary

Research reveals associations between disability and needing mental health support in Somalia, highlighting predictors and barriers.

Introduction

According to recent estimates, 16% of the world’s population – or 1.3 billion people – live with a significant disability (World Health Organization (WHO), 2022a), and 13% live with some form of mental disorder (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2023). Disability and mental health are often not independent, however, with evidence suggesting a well-supported relationship between the two (e.g., Sanderson and Andrews, Reference Sanderson and Andrews2002; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Lloyd and Taylor2006; Emerson et al., Reference Emerson, Honey and Llewellyn2008; Cree et al., Reference Cree, Okoro, Zack and Carbone2020; Augustine et al., Reference Augustine, Bjereld and Turner2022; IHME, 2023). According to the 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study, mental health disorders accounted for 14.95% of the total years lived with disability and 4.92% of total disability-adjusted life-years (IHME, 2023). These global statistics, however, fail to provide a comprehensive picture of the epidemiological landscape of disability and mental health, primarily through overlooking the regional differences that are revealed upon disaggregation. For example, 80% of the global population with disabilities resides in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs) (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2016; WHO, 2022a), as does 82% of the global population with mental disorders (WHO, 2022b). Somalia, a country whose protracted armed conflict since 1991 (Manku, Reference Manku2018) has made it home to some “of the worst humanitarian conditions in the world” (Ononogbu, Reference Ononogbu2018, 117), stands out as one such LMIC where disability and mental health are likely to converge significantly.

The relationship between mental health, disability, poverty and conflict is both dynamic and complex. Previous qualitative research indicates that most Somalis with disabilities are thought to have become disabled due to conflict (Amnesty International, 2015). Likewise, higher poverty levels, stemming from the prolonged humanitarian crisis, also contribute to the suggestion of elevated disability rates among Somalis (WHO, 2010). Poverty and disability are reciprocally related (Groce et al., Reference Groce, Kett, Lang and Trani2011; WHO and World Bank, 2011; Banks et al., Reference Banks, Kuper and Polack2018), particularly for those experiencing multidimensional poverty, which includes monetary, educational and access to basic infrastructure (Mitra et al., Reference Mitra, Posarac and Vick2013). In Somalia, an estimated 90% of the population lives in some form of multidimensional poverty (World Bank, 2022).

Similarly, the decades-long conflict and ongoing humanitarian crisis in Somalia have been described as largely responsible for a ‘collective distress’ among the Somali population and as a key risk factor for the development of mental disorders (WHO, 2010). Indeed, the detrimental effects of armed conflict on the mental health of a population are well documented (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019; Jain et al., Reference Jain, Prasad, Czarth, Chodnekar, Mohan, Savchenko, Panag, Tanasov, Betka, Platos, Swiatek, Krygowska, Rozani, Srivastava, Evangelou, Gristina, Bordeniuc, Akbari, Jain, Kostiks and Reinis2022). Taken together, these factors all likely contribute to what Ibrahim et al. (Reference Ibrahim, Rizwan, Afzal and Malik2022b) have called a ‘mental health crisis’ in Somalia, whereby Somalia’s ongoing conflict has likely led to a heightened demand for effective mental healthcare in a context almost completely devoid of resources for mental health.

Closing the substantial treatment gap for mental health disorders in Somalia, while not uncommon in LMICs (Petagna et al., Reference Petagna, Marley, Guerra, Calia and Reid2023), is likely impeded by additional factors. These include a severe dearth of mental health services, potentially harmful cultural beliefs that stigmatise mental illness (Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Rizwan, Afzal and Malik2022b) and minimal reliable data on the prevalence of mental disorders in the country. The limited data available nonetheless reflects Somalia’s mental health crisis. As of 2010, one in three Somalis suffered, or had suffered, from some sort of mental illness (WHO, 2010). A further situational analysis by the United Nations Human Rights and Protection Group (United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia Human Rights Protection Group (UNSOM HRPG), 2019) indicated high levels of harmful stereotyping of persons with disabilities. A narrow understanding of disability as being related exclusively to physical impairment risks further marginalisation of those with mental health (or other) disabilities with regard to access to services. Misconceptions and significant cultural and attitudinal barriers limit the full and meaningful participation of these citizens (National Disability Agency of Somalia (NDA), 2024).

Despite the well-established connection between disability and mental health and the increased likelihood of both disability and psychological distress in conflict settings, there remains a notable gap in research explicitly exploring the association between disability and mental health as well as the barriers impeding access to mental health services within the Somali context. A better understanding of this relationship has the potential to enhance the living conditions of individuals with disabilities (UNDESA, n.d.; Khaltarkhuu and Sagesaka, Reference Khaltarkhuu and Sagesaka2019; WHO, 2023a) and mental health disorders (Kilbourne et al., Reference Kilbourne, Beck, Spaeth-Rublee, Ramanuj, O’Brien, Tomoyasu and Pincus2018; Moukaddam et al., Reference Moukaddam, Sano, Salas, Hammal and Sabharwal2022; WHO, 2023b) as well as to inform stronger programming and policy.

Therefore, and to bridge these identified research gaps, this study first sought to describe a large sample of Somalis with disabilities in terms of key socio-demographic characteristics related to disability and mental health, specify the percentage of participants with disabilities reportedly needing mental health support but not receiving it, and identify common barriers to accessing mental health support. Next, we sought to investigate the effect, if any, that the level of functional difficulty across different disability domains, the number of disabilities, and other known correlates of mental health and disability have on the probability of Somalis with disabilities endorsing a need for mental health support.

Methods

Study design

This study was a secondary analysis of cross-sectional data collected by the National Disability Agency of Somalia (NDA) as part of their “Disability Data Collection and Needs Assessment Survey” (NDA, 2024). Born from the absence of nationwide disability data in Somalia (SIDA, 2014), the survey began in January 2022 with the aim of understanding the perceptions and priorities of persons with disabilities in Somalia across various service sectors. To gather this information, the NDA – with input from the Somalia Bureau of Statistics, different UN agencies, Organisations for Persons with Disabilities (OPDs) in Somalia and local experts by experience (persons with disabilities involved in the study team) – expanded on a survey tool that had previously been used in disability inclusion studies in South Sudan (The International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2021a) and internally displaced person (IDP) camps in Kismayo, Somalia (IOM, 2021b).

While the original study collected data across a multitude of sectors (e.g., health, housing, water, sanitation and hygiene), this study exclusively focuses on the relationships between disability and the reported need for mental health support. Therefore, a minimal number of variables measured in the original study were included in this study.

Participants

The data used in this study come from a sample of N = 1,367 adults (18 years of age or above) residing in the five regional administrative capitals of Somalia (excluding the country capital of Mogadishu): Kismayo (n = 301), Dhuusamareeb (n = 286), Jowhar (n = 281), Baidoa (n = 266) and Garowe (n = 233) (NDA, 2024). Somaliland was not included within the original study because the NDA’s current reach does not extend to Somaliland. Ultimately, data analyses were performed using (n = 1,355) cases from the original study, whereby the inclusion criteria included those (i) who were ≥18 years of age at the time of data collection and (ii) met the Washington Group on Disability Statistics’ (WG) standard threshold for disability (i.e., responding ‘a lot of difficulty’ or ‘cannot do at all’ to one of the domains in the short-set of questions, further described below). Participants were recruited in the original NDA study through non-probability sampling methods. Purposive sampling was first used via OPDs in each district, followed by snowball sampling to recruit more participants with disabilities. The exclusion criteria for the original NDA study included individuals not self-identifying as having a disability and being below the age of 18.

Data collection

The data reported in this article were collected via household questionnaires administered in-person by local enumerators. The enumerators who collected data were Somali and were trained by the IOM using the WG training materials that had been translated into Somali. Despite efforts by the NDA to recruit enumerators with disabilities, none of them were able to participate in the data collection for the five regions included in the current study. Participant data were collected digitally using Kobo Toolbox.

Instruments and variables

Level of functional difficulty

The WG Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS) was used to assess the level of functional difficulty across six disability domains: vision, hearing, mobility, cognition (remembering), self-care and communication, originally selected for their “simplicity, brevity, universality and comparability” (WG, 2023, para. 7). Developed by a UN Statistics Commission City Group, the WG-SS was designed to facilitate cross-country comparisons of disability data and allows for the disaggregation of outcome indicators based on disability status. Although its validation in the Somali context is not yet established, the WG-SS has undergone extensive testing and validation worldwide (Groce and Mont, Reference Groce and Mont2017) and, as of 2021, is included in the national census of 111 countries (WG, 2022a). The WG-SS was translated for use in the original NDA study by individuals who are fluent in both English and Somali and who have familiarity with the design and aim of the WG-SS questions.

The WG-SS contains six questions – one for each disability domain – that assess the level of difficulty experienced by respondents. Sample items administered directly to the individual include: “Do you have difficulty seeing, even if wearing glasses?” and “Do you have difficulty walking or climbing steps?” (WG, 2022b, 2). Responses are scored on a scale of 1–4, with a greater score indicating a greater level of functional difficulty, ranging from 1 indicating ‘no difficulty’ to 4 indicating ‘cannot do at all’.

Disability status

Aligned with the WG’s recommended criteria (WG, 2020), a score of 3 (‘a lot of difficulty’) or 4 (‘cannot do at all’) on any of the six domains of the WG-SS was used as indicative of disability. A new variable, ‘disability status’, was thus created to determine the percentage of total participants who met this criterion. To determine participant disability status for particular domains, six additional new variables were created within the participant dataset – one for each disability domain – coded as either 1 (i.e., reaching the threshold for disability in that domain of functioning) or 0 (absence of disability in relation to that domain of functioning).

Number of disabilities

The number of disabilities a participant had was then assessed by summing the number of disability domains (vision, hearing, mobility, cognition [remembering], self-care and mobility) present for each participant, with a possible score ranging from 0 to 6.

Need for mental health support

Participants’ need for mental health support was measured dichotomously by asking them “Have you needed psychosocial support like counselling or psychological therapy?” The question was translated with input from local team members familiar with the cultural–linguistic context and the disability and human rights context of the country. Although counselling and psychological therapy is not the typical ‘first-line’ of assistance sought, the terms used were deemed familiar and culturally appropriate by the local experts and experts by experience (persons with disabilities involved in the study team). As such, the translated question was aligned with a common lay understanding in Somalia of the concept of professional counselling or psychological therapy, which did not include spiritual or traditional healing practices. Participants could respond with either ‘yes’ or ‘no’, coded as ‘1’ and ‘0’, respectively.

Barriers to accessing mental health support

Participants who initially responded ‘yes’ to the question “Have you needed psychosocial support like counselling or psychological therapy?” were also asked the question: “Have you been able to get the services you needed?” If they answered ‘no’ to the latter, barriers to accessing mental health support were assessed by asking participants if they had experienced any of the following obstacles to receiving psychosocial support: unavailability of local services, a lack of information, distance, cost of services, a lack of physical access, a lack of safety, discrimination and/or harassment, communication barriers or other. Participants could select multiple options or specify their own options if they chose ‘other’.

Covariates

Consistent with a biopsychosocial model of both health and disability, the strength and direction of the relationship between disability and mental health depend on several interdependent socio-demographic factors. These include, but are not limited to, age (Cree et al., Reference Cree, Okoro, Zack and Carbone2020), gender (Caputo and Simon, Reference Caputo and Simon2013; Noh et al., Reference Noh, Kwon, Park, Oh and Kim2016), marital status (Caputo and Simon, Reference Caputo and Simon2013; Cree et al., Reference Cree, Okoro, Zack and Carbone2020) and employment status (Cree et al., Reference Cree, Okoro, Zack and Carbone2020). Likewise, the literature indicates an association between education and both disability (Kuper et al., Reference Kuper, Monteath-van Dok, Wing, Danquah, Evans, Zuurmond and Gallinetti2014; Houtenville et al., Reference Houtenville, Shreya and Rafal2022) and mental health (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Lu and Xie2020; Kondirolli and Sunder, Reference Kondirolli and Sunder2022). Therefore, the following socio-demographic variables were selected as covariates:

Age

Age was recorded as a continuous variable. Participants were asked their age (in years) during data collection interviews.

Sex

Biological sex at birth was recorded as a dichotomous variable, with males being coded as ‘0’ and females as ‘1’. Participants were asked whether they were male or female during data collection interviews.

Marital status

Marital status was originally recorded as a categorical variable, assessed by asking participants about their marital status during data collection interviews. Possible responses included ‘single’, ‘married’, ‘divorced’, ‘widowed’ or ‘other’. If participants responded with ‘other’, they were asked to specify. For this study, participants who responded with ‘single’, ‘divorced’ or ‘widowed’ in the original study were recoded as ‘0 – no’, while those who responded with ‘married’ were recoded as ‘1 – yes’.

Employment status

Employment status was originally recorded as a categorical variable, assessed by asking participants the question “Are you doing any work that earns you money?” The response options included ‘unemployed’, ‘work sometimes’, ‘employed’ or ‘other’. If participants responded with ‘other’, they were asked to specify. For this study, participants who responded with ‘unemployed’ were recoded as ‘0 – no’, while those who responded with ‘work sometimes’, ‘employed’ or ‘other’ in the original study were recoded as ‘1 – yes’.

Education status

Education status was recorded as a dichotomous variable, assessed by asking participants the following question: “Have you had access to education services?” Participants could respond with either ‘no’ (coded as ‘0’) or ‘yes’ (coded as ‘1’).

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 27.

To achieve the first objective of this study, multiple descriptive analyses were performed. Continuous socio-demographic variables were summarised as a mean, standard deviation and range. Categorical socio-demographic variables were summarised as counts and sample percentages. Likewise, participant’s need for mental health support, ability to access mental health support and the assessed barriers to mental health support were all summarised as counts and sample percentages.

For the second objective of this study, binary logistic regression was chosen to determine the predictive effects of independent variables on the probability of belonging to the self-identified category of needing mental health support. Violations of assumptions of linearity between continuous independent variables (including covariates) and minimal multicollinearity for binary logistic regression were tested using the Box–Tidwell transformation test and by checking variance inflation factor scores, respectively (Harris, Reference Harris2021).

Two binary logistic regressions were performed. The first regression was used to investigate the effect of each of the independent variables – the level of functional difficulty for each WG-SS disability domain and the number of disabilities – on the probability of a participant self-identifying the need for mental health support. A second adjusted model was then used to investigate the same effects while also accounting for the following covariates: age, sex, marital status, employment status and education status. The reference categories for the categorically measured covariates were female for sex, married for marital status, employed for employment status and educated for education status.

Ethics

Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by the NDA and the UN Human Rights. Approval for the use of the anonymised data for the purposes of this secondary analysis was obtained via the School of Linguistic, Speech and Communication Sciences at Trinity College Dublin.

Results

Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics of the selected sample (n = 1,355).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants with disabilities

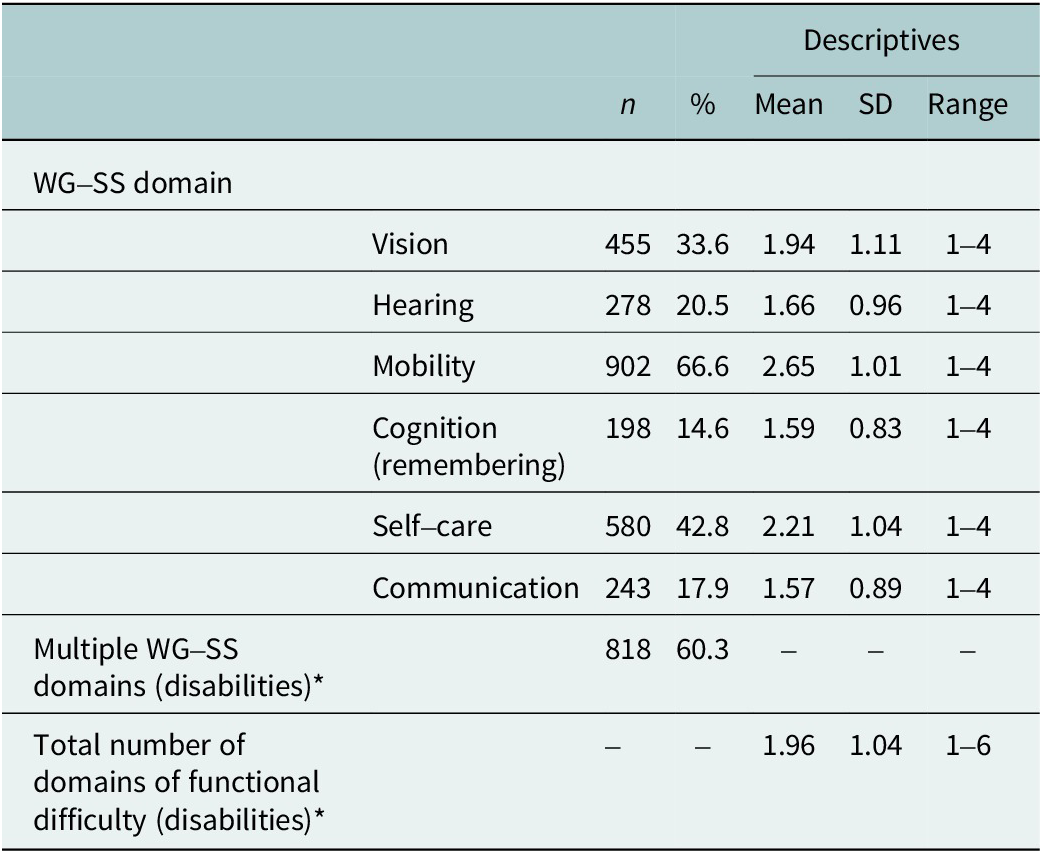

Table 2 summarises the number (n) and percentage (%) of participants with disabilities who met the criteria for each of the WG’s six disability domains and those with disability status in more than one domain, as well as the descriptive statistics for the independent variables in both regression models.

Table 2. Number (n) and percentage (%) of participants’ disability status per disability domain and multiple domains (disabilities) and descriptives of level of functional difficulty for each WG-SS disability domain and the total number of domains of functional difficulty (disabilities) per participant

Note: *participants can report more than one domain of functional difficulty.

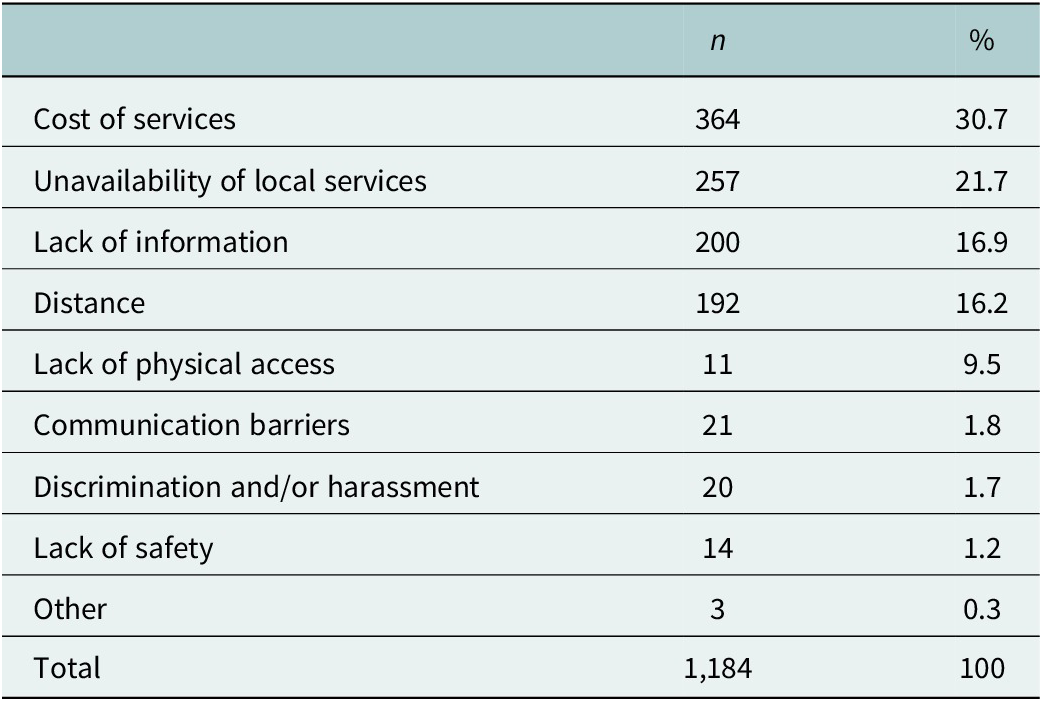

Slightly over half of the participants with disabilities self-identified the need for mental health support (51.7%, n = 695). Among these participants, a significant majority reported not being able to access the mental health support they needed (84.9%, n = 590). Table 3 details the frequency with which each barrier to receiving mental health support was endorsed.

Table 3. Reported barriers to mental health support

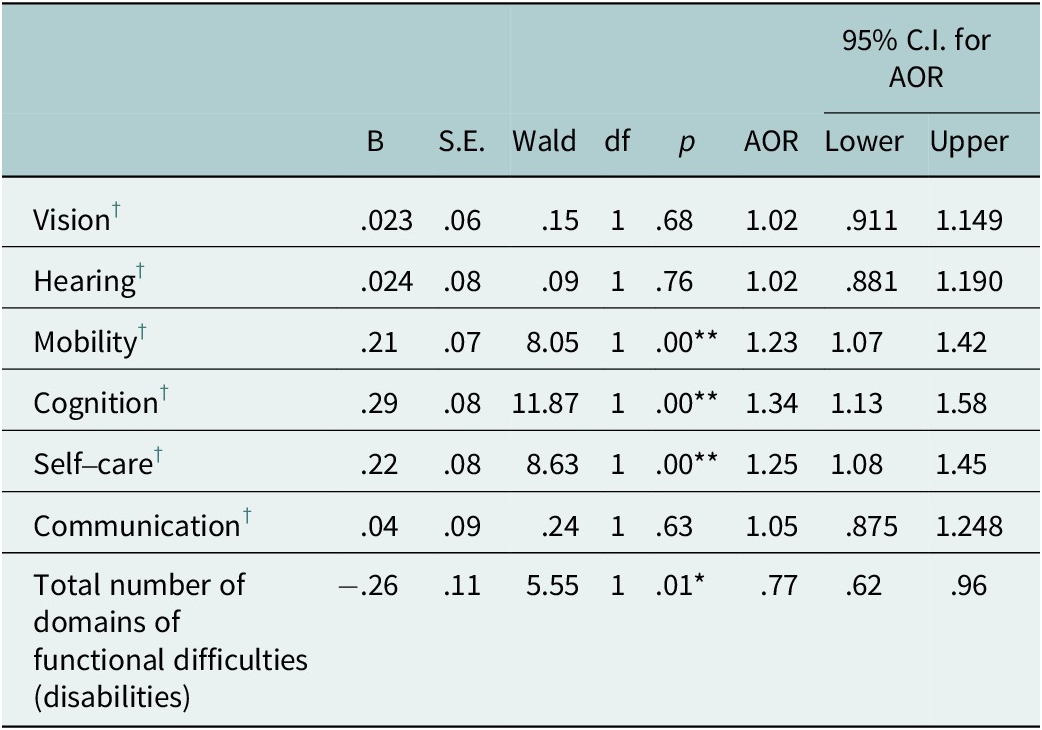

Results – regression (without covariates)

The first regression model was statistically significant (χ2 (7) = 38.38, p < .001) indicating its ability to distinguish between participants with disabilities who self-identified needing mental health support and those who did not. The model explained between 2.8% (Cox and Snell R square) and 3.8% (Nagelkerke R square) of the variance in self-identifying the need for mental health support and correctly classified 56.5% of the total cases. A non-significant Hosmer and Lemeshow test value (p = .524) suggests that the model was a good fit for the data. As shown in Table 4, multiple statistically significant predictors of the likelihood of self-identifying the need for mental health support – compared to not self-identifying such a need – were found: the level of functional difficulty in the mobility (OR = 1.23, 95% C.I. = 1.07–1.42), cognition (OR = 1.13, 95% C.I. = 1.13–1.58) and self-care (OR = 1.25, 95% C.I. = 1.08–1.45) WG-SS domains all significantly increased the likelihood, while only the number of disabilities (OR = .77, 95% C.I. =.62–.96) significantly decreased the likelihood.

Table 4. Logistic regression (without covariates) predicting the likelihood of self-identifying the need for mental health support

Note: *p < .05 and **p < .001, denoting statistically significant thresholds.

† Each of the six domains of functional difficulty in the WG-SS.

Results – regression (adjusted model)

The second regression model was statistically significant (χ2 (12) = 64.291, p,.001), indicating its ability to distinguish between participants with disabilities who self-identified needing mental health support and those who did not. In a slight improvement over the first model, the second model explained between 4.7% (Cox and Snell R square) and 6.2% (Nagelkerke R square) of the variance in self-identifying the need for mental health support and increased the rate of correctly classified cases to 60%. A non-significant Hosmer and Lemeshow test value (p = .163) suggests that the model was a good fit for the data. Table 5 demonstrates the effect of each independent variable and covariate on the probability of self-identifying the need for mental health support, compared to not self-identifying such a need. Similar to the first model, statistically significant predictors of an increased likelihood of self-identifying the need for mental health support were found in the level of functional difficulty in the mobility (AOR = 1.25, 95% C.I. = 1.07–1.45), cognition (AOR = 1.39, 95% C.I. = 1.17–1.65) and self-care (AOR = 1.26, 95% C.I. = 1.09–1.47) WG-SS domains, while the number of disabilities (AOR = .76, 95% C.I. =.61–.95) significantly decreased the likelihood. Additionally, the adjusted regression results indicated that being male (AOR = .69, 95% C.I. = .55–.87) and unmarried (AOR = .63, 95% C.I. =.50–.79) were significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of self-identifying the need for mental health support compared to being female and married (respectively).

Table 5. Adjusted logistic regression predicting the likelihood of self-identifying the need for mental health support

Note: *p < .05 and **p < .001, denoting statistically significant thresholds.

† Each of the six domains of functional difficulty in the WG-SS.

Discussion

This study first sought to describe a large sample of Somalis with disabilities in terms of key characteristics, investigate the prevalence of their self-identified need for mental health support and identify the most endorsed barriers to accessing such support. Particularly noteworthy were the significant levels of unemployment and lack of education among the participants with disabilities. Results also demonstrated that most participants with disabilities self-identified the need for mental health support. This finding is consistent with previous research, which found that 31% of IDPs with disabilities in Kismayo, Somalia expressed mental health concerns (IOM, 2021b). However, as mental health is heavily stigmatised in Somalia (Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Rizwan, Afzal and Malik2022b), it seems possible that participants in this study underreported the need for mental health support.

Concerningly, only a small proportion of those who identified the need for mental health support reported being able to access the required services. This aligns with previous research from sub-Saharan Africa, where the treatment gap for mental disorders is estimated to range from 75% to 90% (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Alem, Schneider, Hanlon, Ahrens, Bandawe, Bass, Bhana, Burns, Chibanda, Cowan, Davies, Dewey, Fekadu, Freeman, Honikman, Joska, Kagee, Mayston, Medhin, Musisi, Myer, Ntulo, Nyatsanza, Ofori-Atta, Petersen, Phakathi, Prince, Shibre, Stein, Swartz, Thornicroft, Tomlinson, Wissow and Susser2015). The profound scarcity of mental health resources in Somalia (Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Malik and Noor2022a,Reference Ibrahim, Rizwan, Afzal and Malikb) was further reflected by ‘unavailability of local services’ being a frequently mentioned barrier to care noted by participants with disabilities. To address this barrier, task-sharing, a practice involving the redistribution of care from specialists to non-specialist health workers (NSHWs) (van Ginneken et al., Reference van Ginneken, Tharyan, Lewin, Rao, Romeo and Patel2011; Le et al., Reference Le, Eschliman, Grivel, Tang, Cho, Tay, Li, Bass and Yang2022), provides a promising approach, as it allows for an increase in the availability of human resources (Singla et al., Reference Singla, Kohrt, Murray, Anand, Chorpita and Patel2017). Previous research has advocated for the expansion of task-sharing programmes within Somalia, highlighting the precedent of the Marwo Caafimaad program – a task-sharing initiative to address maternal health issues in the country (Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Malik and Noor2022a). While task-sharing has been shown to be effective in ameliorating mental distress in LMICs (Kakuma et al., Reference Kakuma, Minas, van Ginneken, Poz, Desiraju, Morris, Saxena and Scheffler2011; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Kohrt, Murray, Anand, Chorpita and Patel2017), there are likely several barriers to its implementation for mental health in Somalia (e.g., Le et al., Reference Le, Eschliman, Grivel, Tang, Cho, Tay, Li, Bass and Yang2022).

One such barrier may be the general acceptability and feasibility of these interventions (Padmanathan and De Silva, Reference Padmanathan and De Silva2013). A task-sharing programme that could address this challenge is ‘Islamic Trauma Healing’ (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, Feeny, Dolezal, Klein, Marks, Graham and Zoellner2021). Developed in collaboration with Somali refugees, this group-based, lay-lead intervention integrates Islamic principles into evidence-based psychotherapies. Previous research demonstrates its feasibility, acceptability and preliminary effectiveness in reducing psychological distress among Somali Muslims (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, Feeny, Dolezal, Klein, Marks, Graham and Zoellner2021; Zoellner et al., Reference Zoellner, Bentley, Feeny, Klein, Dolezal, Angula and Egeh2021). Given Somalia’s predominantly Muslim population (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, Feeny, Dolezal, Klein, Marks, Graham and Zoellner2021), there is significant potential for further investigations into the efficacy of Islamic Trauma Healing as a community-based programme to ameliorate mental distress among Somalis with disabilities.

Enhancing task-sharing for mental health services within Somalia could also be achieved through implementing the WHO’s Mental Health Action Gap (mhGAP) programme, as highlighted by Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Rizwan, Afzal and Malik2022b. Indeed, the mhGAP is embedded in the ‘2019–2022 Somali Mental Health Strategy’, which emphasises its implementation as an essential activity and highlights positive outcomes from previous mhGAP training sessions for Somali health workers (Federal Ministry of Health and Human Services, 2019). These implementation efforts, however, may be hindered by the lack of a “coherent, consolidated human resource development plan” (Federal Ministry of Health and Human Services, 2019, 14). To address this, the ‘C4 Framework’ (Bolton et al., Reference Bolton, West, Whitney, Jordans, Bass, Thornicroft, Murray, Snider, Eaton, Collins, Ventevogel, Smith, Stein, Petersen, Silove, Ugo, Mahoney, el Chammay, Contreras, Eustache, Koyiet, Wondimu, Upadhaya and Raviola2023) is worth exploring. Drawing from the mhGAP guide, this framework offers a comprehensive, collaborative and community-based (C4) care model that provides detailed guidance on how to bolster human resources for the delivery of sustainable and feasible task-sharing mental health services in low-resource settings. Continued research into how these task-sharing initiatives can be optimally integrated into the Somali healthcare system is essential, as – due to the disruption of health services caused by humanitarian emergencies – there is substantial opportunity for sustainable improvements in mental healthcare provision (Epping-Jordan et al., Reference Epping-Jordan, van Ommeren, Ashour, Maramis, Marini, Mohanraj, Noori, Rizwan, Saeed, Silove, Suveendran, Urbina, Ventevogel and Saxena2015).

Interestingly, discrimination and/or harassment was only mentioned 20 times as a barrier to accessing mental health support. This finding is inconsistent with a meta-synthesis of 41 qualitative studies that found that discrimination often discouraged persons with disabilities in LMICs from seeking healthcare (Hashemi et al., Reference Hashemi, Wickenden, Bright and Kuper2022). In a context like Somalia, where both disability (Manku, Reference Manku2018) and mental health (Manku, Reference Manku2018; Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Rizwan, Afzal and Malik2022b) are heavily stigmatised, one would anticipate discrimination against persons with disabilities seeking mental healthcare to be a frequent occurrence. This discrepancy may stem from a hesitancy to report experiences of discrimination, a common cross-contextual occurrence (e.g., Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Kim, Chung, Park, Sorensen and Kim2021; Perone, Reference Perone2023). Likewise, Somalis with disabilities may underreport discrimination due to “internalised oppression” – wherein marginalised groups acknowledge their secondary status and view their unfair treatment as nondiscriminatory (Krieger, Reference Krieger1999, 324). Nevertheless, the unexpected nature of these findings within the context of previous research (e.g., Hashemi et al., Reference Hashemi, Wickenden, Bright and Kuper2022) calls for further exploration. A more qualitative approach may be needed to better understand the experiences of discrimination that persons with disabilities in Somalia encounter, and how these experiences affect their ability to access mental health services. This study also sought to explore the independent impact of different disability domains, the number of disabilities and related covariates on the probability of self-identifying a need for mental health support. The results indicate that an increasing level of functional difficulty in the cognitive domain of disability was associated with the greatest odds of self-identifying the need for mental health support, consistent with what previous research suggests (e.g., Horner-Johnson et al., Reference Horner-Johnson, Dobbertin, Lee and Andresen2013; Cree et al., Reference Cree, Okoro, Zack and Carbone2020). However, our results differ from those of Horner-Johnson et al. (Reference Horner-Johnson, Dobbertin, Lee and Andresen2013) regarding the impact of mobility disabilities. While Horner-Johnson et al. found that persons with a mobility disability had lower odds of reporting poor mental health compared to those with a hearing disability, this study’s results demonstrate that Somalis with a mobility disability had increased odds of acknowledging the need for mental health support, whereas those with a hearing disability did not. This difference could be due, in part, to divergent methodological characteristics between this study and that of Horner-Johnson et al. (Reference Horner-Johnson, Dobbertin, Lee and Andresen2013). Contextual differences, such as potentially greater infrastructural and societal accommodations for Americans with a mobility disability than their Somali counterparts, may also contribute to this observed discrepancy.

Being female was also associated with greater odds of self-identifying the need for mental health support. This may be accounted for by a greater likelihood of females experiencing internalised mental health problems – such as anxiety and/or depression – compared to men (Seedat et al., Reference Seedat, Scott, Angermeyer, Berglund, Bromet, Brugha, Demyyttenaere, de Girolamo, Haro, Jin, Karam, Kovess-Masfety, Levinson, Mora, Ono, Ormel, Pennell, Posada-Villa, Sampson, Williams and Kessler2009; Riecher-Rössler, Reference Riecher-Rössler2016; Otten et al., Reference Otten, Tibubos, Schomerus, Brähler, Binder, Kruse, Ladwig, Wild, Grabe and Beutel2021) with the greatest disparity in sub-Saharan Africa (Yu, Reference Yu2018). Furthermore, more females receive mental health care than males (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2023), suggesting that women may be more willing to seek support than men. While the data from the NIMH (2023) is from the United States – and thus, not representative of Somalia – it nonetheless offers a potential explanatory mechanism for the results found in this study. The findings of this study also support those of Moodley and Graham (Reference Moodley and Graham2015), who found that the intersection of gender and disability has particularly negative outcomes for women. Therefore, in addition to those with a cognitive or mobility disability, Somali females with a disability may be especially interested in, or especially benefit from, participating in mental health interventions.

Surprisingly, an increasing number of disabilities was associated with a lower likelihood of self-identifying the need for mental health support in this study. This contradicts the findings by Horner-Johnson et al. (Reference Horner-Johnson, Dobbertin, Lee and Andresen2013), who discovered that having more than one disability significantly increased the odds of an individual reporting poor mental health. Similarly, Cree et al. (Reference Cree, Okoro, Zack and Carbone2020) highlight how participants who had more than one disability had the highest prevalence of frequent mental distress and diagnosed depressive disorders. Differences in the applied criteria for being considered to have a disability between this study and those of Horner-Johnson et al. (Reference Horner-Johnson, Dobbertin, Lee and Andresen2013) and Cree et al. (Reference Cree, Okoro, Zack and Carbone2020) may contribute to this discrepancy. Indeed, there are several distinct conceptual models of what disability is, each of which can have different implications for how it is measured (Palmer and Harley, Reference Palmer and Harley2012).

Given the extreme dearth of mental health resources in Somalia (Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Malik and Noor2022a), it seems crucial to prioritise certain individuals for intervention. The results of this study indicate Somalis with cognitive or mobility disabilities and Somali females with disabilities (or an intersection of the two) may be particularly receptive to practical interventions targeting the amelioration of mental distress.

This study is not without limitations. First, the cross-sectional data collection method used in the original NDA study hinders this study’s ability to establish any causal dimension to the relationship between disability and the self-identified need for mental health support. Nonetheless, the results of this study indicate a weak, largely positive association between the two variables in the Somali context, suggesting the potential for a future longitudinal study to explore causality further. A second limitation of this study is the exclusion of an explicit intellectual disability variable from the regression models. This is, in part, due to the lack of a WG-SS question that specifically targets intellectual disability. While people with intellectual disabilities may respond with significant functional difficulties in multiple of the WG-SS domains – such as self-care, communication and cognition – the WG-SS may not fully capture the suggested complexity and heterogeneity of intellectual disability (Zhang and Holden, Reference Zhang and Holden2022). Given the highest regional prevalence rates of intellectual disabilities are found in LMICs (Nair et al., Reference Nair, Chen, Dutt, Hagopian, Singh and Du2022), especially in sub-Saharan Africa (Olusanya et al., Reference Olusanya, Kancherla, Shaheen, Ogbo and Davis2022), and the significant co-occurrence of intellectual disabilities and poor mental health (Emerson and Hatton, Reference Emerson and Hatton2007; Munir, Reference Munir2016; Totsika et al., Reference Totsika, Liew, Absoud, Adnams and Emerson2022), it is essential to explicitly include them in investigations into the relationship between disability and mental health going forward. Future research should build on these results by incorporating the measurement of intellectual disability in the Somali context to better understand its impact on mental health outcomes.

Third, our regression analyses had a limited scope, as only some of the theoretically supported covariates were included in the adjusted model. The original study contained additional social determinants of mental health variables that may influence the self-identified need for mental health support among Somalis with disabilities – such as their ability to access public areas (Libertun de Duren et al., Reference Libertun de Duren, Salazar, Duryea, Mastellaro, Freeman, Pedraza, Rodriguez-Porcel, Sandoval, Aguerre, Angius, Ariza, Artieda, Bonilla, Cabrol, Guerra, La Forge, Chacón-Martínez, Mitchell, Pineda, Pinzon-Caicedo and Poitier2021), water and sanitation facilities (Simiyu et al., Reference Simiyu, Bagayoko and Gyasi2021) and food sources (Na et al., Reference Na, Miller, Ballard, Mitchell, Hung and Melgar-Quinoñez2018). Future research should expand the number of theoretically supported variables as covariates to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships between disability and mental health in Somalia.

Finally, the use of non-probability sampling techniques in the original NDA study from which this study’s data originates introduces the potential for selection bias (Andridge et al., Reference Andridge, West, Little, Boonstra and Alvarado-Leiton2019) and thus “inaccurate estimations” of the discovered associations (Shringarpure and Xing, Reference Shringarpure and Xing2014, 902). Furthermore, such sampling techniques restrict the ability to generalise the study’s findings to the entire population of Somalis with disabilities (Alvi, Reference Alvi2016). Future research should attempt to investigate the relationship between disability and mental health in Somalia using more probability-based sampling techniques.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations, this study provides valuable insight into the concerning mental health condition of persons with disabilities in Somalia. This study reveals priority areas for practical interventions, including females, individuals with cognitive or mobility disabilities and individuals experiencing an intersection of these factors. However, further research is essential to gain a more detailed understanding of the mental health challenges that Somalis with disabilities face and how to effectively support this population. In particular, research that investigates the feasibility of delivering established low-resource mental health interventions within the Somali disability context is recommended. In sum, this study serves as an important steppingstone, highlighting the pressing need for future research and practical efforts aimed at ameliorating the mental health outcomes of persons with disabilities in Somalia.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.66.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.66.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author M.A.J. (upon reasonable request), as an employee of the NDA of Somalia, which originally collected the data.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the collaborators and individuals who made this work possible. Specifically, the authors would like to thank those staff members of the NDA of Somalia and the UN Human Rights and Protection Group Somalia who were involved in both the original data collection and the analysis that is this study. The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to the Somali participants who donated their valuable time and energy to kindly participate in the original NDA of Somalia study from which this current study is born.

Author contribution

M.A.J., K.Y. and C.J. conceived the study. A.H.A. supported data collection. C.Z., F.V. and C.J. analysed the data. C.Z. was the principal author in drafting this manuscript, supervised by F.V. and C.J. All authors contributed to the interpretation, editing of the paper and approval of the version for submission.

Financial support

Data collection costs were supported by funding from UN agencies in Somalia. The analysis costs were covered in part through pro-bono contributions and in part funded by the SADIE Network (Strengthening evidence-based Action on Disability and Inclusion in Emergencies).

Competing interest

M.A.J. is employed by the National Disability Agency of Somalia; A.H.A and K.Y. are employed by the UN Human Rights and Protection Group Somalia. C.Z., F.V. and C.J. declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics standard

All authors declare to adhere to the publishing ethics of Global Mental Health. The ethics for original data collection were granted by the National Disability Agency of Somalia and the UN Human Rights and Protection Group Somalia (SLSCS TT87). Participant consent was verbal and recorded by each enumerator in the Kobo toolbox system prior to proceeding with data collection.

Comments

Dear Professors Bass and Chibanda,

We are pleased to submit our manuscript “The unmet need for mental health support among persons with disabilities in Somalia: principal correlates and barriers to access” to be considered for publication in Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health.

While previous research indicates concerningly high rates of disability and mental health in Somalia, we are not aware of any previous studies that have simultaneously explored both disability and mental health-related factors in the Somali context. This study marks the first such exploration, analysing data collected by the National Disability Agency of Somalia to identify how increasing levels of functional impairment, reported across different disability domains (i.e., visual, hearing, cognition), number of concomitant disabilities, and other empirically supported variables (such as employment and sex) are associated with the likelihood of self-identifying the need for mental health support among a sample (N = 1355) of Somalis with disabilities, as well as identify how prevalent this need is among the sample and the common barriers to such mental health support.

Results indicate that the majority of participants expressed a need for mental health support, but that only 15% reported being able to access it. The most frequently cited barriers that inhibited their access were the cost of services, the unavailability of local services, and a lack of information. We also found that increasing levels of functional impairment in the cognitive, mobility, and self-care domains of disability were associated with an increased likelihood of a participant self-identifying the need for mental health support, as were being female, and being married. Interestingly, an increasing number of disabilities was associated with a lower likelihood of the same.

The results of this study point to potential areas of prioritisation for mental health interventions in Somalia, a country that has limited mental health resources. It is our hope that the results of this study will be useful in informing future research endeavours, as well as informing policy and mental health programming within Somalia. For this reason, it is our belief that this manuscript could be of particular interest to the readership of Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health.

The manuscript is an original piece of research and has been prepared in accordance with the journal style. The manuscript is 4,999 words long (excluding title page, abstract, references, and 5 tables and their captions/notes). The manuscript has not been previously published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere. I have assumed the role as corresponding author and all co-authors have agreed to the order of the author list. I look forward to hearing back from you regarding this submission.

I greatly look forward to hearing back from you regarding this submission.

With thanks for consideration,

Chad Zemp

Centre for Global Health, Trinity College Dublin