Research Aim and Background

In 1736, the Salvadori firm in Trento recorded in its main ledger a credit to Antonio Calavin for the sum of 75 florins, paid to Norsa of Mantua to redeem Antonio’s son, a soldier. While we have no further details about Calavin, he was most likely a common subject of the prince-bishopric. It is expected that Norsa belonged to a well-established family in the Jewish community of Mantua, which was known to be active in the redemption of prisoners; he may have indeed been the powerful banker Abraham Norsa.Footnote 1 Antonio’s debt would be transferred in 1747 to a newly established book of deposits, in which the lenders noted interest due at 5 percent per annum according to a notary’s scritto (written deed). In 1737, Salvadori had advanced 900 florins to the Reverend Cristoforo de Megliori to pay for a bequest in favor of a religious confraternity; the loan was granted through a notarial deed and secured by the mortgage of a piece of land. In 1752, Antonio Crivelli, an important patrician in Trento, received 5,000 florins from the Salvadori family, but there was no notarial intervention in this case as the lenders were satisfied with an obligo (IOU) signed by the borrower.Footnote 2

These are just a few examples of credit transactions entered into by the Salvadori firm, a family business based in Trento, the capital of a prince-bishopric in the central-eastern Italian Alps.Footnote 3 Although located in a mountainous region and based primarily on a rural economy, the prince-bishopric and the adjacent county of Tyrol enjoyed a strategic position at the crossroads of important trade routes linking Northern Italy, and particularly Venice, with Austria, Eastern Switzerland, and Southern Germany. The conditions were favorable in the early modern period for the development of a silk proto-industry centered on a group of enterprising merchants, who had their headquarters in Rovereto, south of Trento, in the Italian-speaking area of South Tyrol.Footnote 4 These and other long-distance merchants met every three months at the international trade and exchange fairs in Bolzano/Bozen, north of Trento, in German-speaking Tyrol, where they negotiated and settled payments with merchants from a wide area extending from Northern Italy to Central Europe.Footnote 5

Compared to Bolzano and Rovereto, Trento was a less dynamic center; however, in the 1740s, the bishopric’s capital and its district did have a relatively large population totaling some twenty thousand inhabitants. The Salvadori family owned one of the most important commercial houses in the region, as documented by their repeated election to the Merchant Court in Bolzano, the tribunal that settled disputes among merchants attending the fairs. By the mid-eighteenth century, after having amassed a fortune from trading in olive oil, snuff, and other goods, the Salvadori family was already engaged in the lucrative silk trade.Footnote 6 They epitomized the typical preindustrial firm that diversified its business portfolio by combining trade, manufacturing, and lending activities, often making it difficult to distinguish the financial from the commercial entrepreneur.Footnote 7 Thus, it is no surprise that in 1785, a letter from Paris was addressed to “messieurs les freres Salvadori banquiers.”Footnote 8

As is well known, merchant-bankers emerged in Central and Northern Italy in the late Middle Ages when a group of merchants who engaged in long-distance trade and attended the most important fairs gained supremacy in international banking and finance. They operated as partnerships employing their own capital and, to a lesser extent, funds contributed by a small circle of relatives, friends, and clients to invest in commercial, manufacturing, and financial activities.Footnote 9 In some periods, and in places like Florence, Genoa, and Venice, some merchant-bankers made lending their core business, while many others engaged in lending as a secondary pursuit, as indeed was the case with the Salvadori family.

Our study focuses on the local lending activities of these merchant-bankers in order to improve our understanding of how early modern credit markets functioned in a “less-developed” economy. In recent decades, there has been a growing interest among economic historians in credit markets in rural regions, which has provided much evidence about how credit markets functioned in institutional, social, and economic contexts different from those of highly commercialized societies in England, France, or the Low Countries.Footnote 10 The systematic recording of loans by Salvadori allows us to investigate the operation of credit in a region that, although predominantly rural, could take advantage of the presence of merchant-bankers with available liquidity to meet the financial needs of different social strata. Drawing on the plentiful business records, we can situate the financial strategies of these merchants in the broader context of social relations, which is essential to understanding how the larger framework in which the Salvadori family operated, and their standing within it, influenced the nature of private lending, and to what extent the firm’s liquidity “trickled down” to the local community. For this study, we do not consider sales credit but only interest-bearing loans, and in particular those granted (with some exceptions) outside the financial circuits of the Bolzano fairs.

Private lenders, like Salvadori, were joined in the credit market in Trento by other types of actors. A monte di pietà (nonprofit pawn bank) had been founded in 1523 to meet the small credit needs of the “lesser poor”; like many similar institutions in Italy, its purpose was to combat usury.Footnote 11 By the eighteenth century, the pawn bank had opened its doors to wealthier customers, as evidenced by the fact that among the items allowed as collateral were also jewelry and precious metals.Footnote 12 In addition, other nonspecialized lending institutions, such as religious bodies and charitable foundations called ospedali, practiced lending as a secondary activity to invest their wealth.Footnote 13

Formal and informal channels of credit coexisted in the bishopric, as elsewhere in Italy. Credit often took the form of peer-to-peer lending, with people in search of liquidity turning to relatives, friends, and neighbors to meet their financial needs, while studies of large cities, such as Milan, have shown that notaries played an increasingly important role in the eighteenth century in facilitating credit, securing debts, and easing the transfer of information between lenders and “more distant” borrowers.Footnote 14 Unfortunately, there is almost no literature on the credit market in early modern Trentino-Tyrol, except for some research on civil debt trials, the credit activities of local welfare institutions, and a comparative study of notarial loans in Trento and Rovereto.Footnote 15 The latter, in particular, shows that the credit market in Trento was less dynamic than in Rovereto, but we cannot fully appreciate the extent to which notarial loans are representative of local credit activities. The Salvadori case provides an opportunity to investigate the financial strategies of a family business that operated at the intersection of formal and informal credit by engaging in peer-to-peer lending with and without notarial intervention.

Thus, our work straddles two main strands of the literature concerning the social embeddedness of credit relationships and the role of notaries. Social ties can influence lending in several ways: a strong lender-borrower relationship, based on belonging to the same social group or having the same business connections, reduces information asymmetries and increases the generation of trust that supports credit extension. However, a closer relationship could create a feeling of obligation on the part of the lender to a counterparty in need of money. Far from being perfectly rational actors eager to maximize their economic return, economic agents followed multiple logics in their decisions.Footnote 16 Social affiliations and aspirations could profoundly influence lending decisions, in line with Laurence Fontaine’s assertion that “merchants’ portfolios of debt did not escape the complexity of their social roles and the contradictions these forced on them: on one hand, they had to meet their obligations as members of immediate and wider family groups, of networks of ‘friends’ and as providers of work, and on the other, they had to invest in the various centres of power to realize their strategies for upward mobility and market conquest.”Footnote 17 This connection of credit transactions to social hierarchies and power relations is not new. In their study of interpersonal credit ties among elite families in Renaissance Florence, McLean and Gondal observed that the core participants belonged to the inner circles of the most commercially and politically active Florentines, with a close intertwining of economic and social motivations.Footnote 18 In his study on early modern Venice, Shaw found a “network of patronage and favour” of which trusted notaries were an integral component.Footnote 19

The role of notaries constitutes the second stream of literature that forms the background of this study. Social ties affected not only the decision to make a loan but also the type of instrument used. Hierarchies and social proximities in the lender-borrower relationship were reflected in the different means used to register a debt; for example, loans to a relative or friend were usually recorded on a private note or in a ledger because taking them to notary would signify a lack of trust.Footnote 20 Scholarly interest in the “shadow” credit market that pivoted on notaries was particularly stimulated by the pioneering studies of Hoffman, Postel-Vinay, and Rosenthal.Footnote 21 As these authors documented for Paris, and more recently for France as a whole, notaries contributed to the expansion of credit by acting as brokers between lenders and borrowers. They did not simply make and keep legal records, for which they provided the publica fides (public faith) as was typical in countries influenced by Roman law but also exploited their informational advantage to act as intermediaries. By connecting those in need with those who had money available, and by providing lenders with information about borrowers and their collateral, notaries helped overcome the problem of asymmetric information, increased trust, and reduced transaction costs in a credit market that was growing ever more impersonal.Footnote 22 In a “priceless market” in which a lender’s decision to make a loan depended more “on personal information about borrowers and extra-market relationships with them” than on interest rates,Footnote 23 notaries expanded opportunities to grant and receive credit beyond the circle of relatives and acquaintances, freeing credit from social ties and opening it up to all social classes.

As other scholars have shown, however, notaries did not assume the same role in all places. In the Netherlands, aldermen and notaries were active in the drafting of loans, but the requirement that all transactions involving real estate be publicly recorded deprived them of the informational advantage enjoyed by their Parisian counterparts. As a result, they did not act as financial intermediaries like French notaries did. Gelderblom, Hup, and Jonker argue that, in large commercial cities, merchants made little use of notaries; even business ledgers and privately written obligations were allowed as legal evidence, reducing the need for notaries. Because registering contracts cost time and money, lenders and borrowers turned to notaries and aldermen when they needed their professional expertise to draft the formalized contract or were “unsure about their counterparty,” while preferably resorting to private agreements with relatives, friends, and business associates.Footnote 24

Other studies focusing on rural contexts have highlighted the pervasiveness of informal credit. Investigating some small rural communities in southern Alsace, Elise Dermineur argued that the high degree of social proximity reduced the need for notarial credit. In the Parisian credit market, notaries could use their privileged position to reduce information asymmetries between lenders and borrowers: “in small rural communities with strong bonds, individuals could easily overcome this asymmetry of information, which in turn explains the vitality of the non-notarised lending channel.”Footnote 25 Indeed, by investigating formal and informal liabilities through notarized records and probate inventories, Dermineur estimates a similar volume of transactions in notarized and nonnotarized credit markets.Footnote 26 The importance of “mutual trust and an intimate knowledge of the creditworthiness of borrowers” in small communities was also emphasized by Lindgren with regard to the Norra Möre district in rural Sweden. Here, the role of notaries in registering debts never became established, but this did not prevent the development of a vibrant informal credit market based on private promissory notes and dominated by a few “parish bankers.”Footnote 27 Notaries did not record loans in Wildberg, but Ogilvie, Küpker, and Maegraith portray a different picture for this locality in rural Württemberg. They document a diverse credit market that was based less on personalized credit relationships than might be assumed and had no local moneylenders monopolizing it. The authors speculate that communal and state officials there may have played the “debt recording and brokerage role” that notaries had in France, but the need to obtain communal or state authorization for borrowing and the costly fees for permits reduced the use of formal debt certificates.Footnote 28 In contrast, in the Saar-Moselle region after the French Revolutionary period, notaries were active in certifying loan contracts, and yet many debt certificates were still issued informally.Footnote 29

Against the backdrop of these studies, the Salvadori case allows us to address some key questions: What types of credit instruments did this family of merchant-bankers use, and what was their position in the local credit market? Who were the main beneficiaries of their lending activities? More importantly, what were the social underpinnings of the Salvadori credit network, and to what extent did the latter reflect the social structure of the local community? Finally, what role did notaries play? To answer these questions, we draw on business records that provide a complete picture of the firm’s loans, including notarized loans and private agreements. They also provide detail on the duration of the loans, repayment terms, and interest rates, which often do not appear in probate inventories. In addition, we can track loans from origin to extinction and identify actors connected to the credit relationship other than borrowers and notaries, such as guarantors, payers, and previous or subsequent debtors or creditors.

Unfortunately, analysis of motives is necessarily based on indirect evidence since in only a few cases are they specified in the ledgers, and correspondence cannot be useful in investigating local credit, as this was usually negotiated face-to-face. Nonetheless, the wealth of data in the archives provides detailed knowledge of the relationships between the Salvadori family and their clients; this knowledge is vital to explore the social dimension of credit and the role of notaries, thus helping to shed light on the functioning of a credit market somewhat remote from the highly commercialized economies of Northwest Europe.

Our analysis is structured as follows. After briefly describing the Salvadori firm and introducing the main source, we use descriptive statistics to provide initial evidence on the lending activities of these merchants by examining the characteristics of loans. To investigate the social dimension of credit, we then examine the characteristics of borrowers in relation to their geographic and social proximity to the Salvadori family, and apply social network analysis to visualize the “extended” credit network and to identify the most prominent figures by position of centrality and influence. Among these, we find both notaries and nonnotarial figures, primarily borrowers belonging to the local elite whose role in the Salvadori credit network is explored in more detail. Finally, we focus on notaries and their function. After comparing the main characteristics of notarized and nonnotarized loans, we investigate how the degree of social proximity between lenders and borrowers affected the use of formal agreements.

The Deposit Ledger and the Salvadori Standing in the Local Credit Market

The origins of the Salvadori firm date back to the 1660s, when two brothers, Valentino (1641–1692) and Isidoro (1645–1701), moved from Mori, a locality in the bishopric, to Trento, where they started a retail store. Another store soon followed in Pergine, east of the principality’s capital. The two brothers and their offspring maintained joint ownership until 1747, when the Salvadori family in Trento separated from the family branch in Pergine (which had only one descendant) and retained control of the business. By that time, the retail store in Trento had ceased operation, the management of the store in Pergine had been entrusted to a nonkin partner, and the business portfolio included the manufacture of silk at the firm’s reeling and throwing mills in Trento and Calliano, a village south of Trento. The silk trade fueled exports, further consolidating the Salvadori relationship with their counterparts across the Alps.Footnote 30

The division between the two branches of the family required the compilation of a complete inventory of the assets and liabilities of the firm. On that occasion, Salvadori drew up a list of all the interest-bearing credits, which were transcribed from the main ledger into a new book of deposits for a total amount of some 50,000 florins.Footnote 31 All loans belonged to the Salvadori as a family and as a business unit, making it impossible to distinguish between personal and commercial loans. The loans represented a smaller but substantial share of the value of the business (which was 230,000 florins), exceeding that of the family’s real estate. Financial activities were on the rise, thus increasing the need to keep careful track of payments for interest and installments; this is most likely why the Salvadori family created a separate deposit book.

At that time, the main figures were Isidoro’s sons, Angelo (1681–1756), who was unmarried, and Valentino (1694–1768), married to the only daughter of a wealthy merchant, Francesco Mozer. On the death of Valentino, the Mozer real estate holdings were divided among Valentino’s children, who acquired individual ownership for the first time while retaining the assets of the business as undivided family property. In addition, Mozer left a share in a partnership—Mozer, Kloz & Co.—which was liquidated in the mid-1760s, and the sum deposited by Mozer’s heirs in the main firm. A combination of factors—the election of Valentino’s son, Isidoro (1721–1787) to the Merchant Court in Bolzano, Valentino’s move to Calliano, and a change in business strategies—must have contributed to shifting the center of gravity of the firm’s financial activities to the Bolzano fairs, causing a scaling back of the local lending activity by the 1760s.Footnote 32

The deposit ledger is the central source for this study. The ledger shows the accounts of borrowers kept in the Venetian system, which means the Dare and Avere sections were placed on two facing pages. These, respectively, record the amounts due for principal and interest and the amounts actually paid (Figure 1). In 1747 Salvadori transcribed all outstanding loans dating back to 1724, and later recorded other loans.Footnote 33 The deposit book documents 152 credit transactions undertaken with 104 distinct borrowers, with a total value of 168,397 florins. Except for one in 1786, most of the loans were issued in the late 1740s and early 1750s, when financial activity of the firm peaked, and the remainder issued by 1767 (Figure 2).Footnote 34 It is worth noting that more than two-thirds of the credit transactions, totaling 130,000 to 140,000 florins, involved the actual disbursement of money; in other cases, the credit was received from a third party or was a sales credit turned into an interest-bearing loan.

Figure 1. Account held by Giacomo Antonio Bortolazzi in the Salvadori deposit ledger.

Source: Photo from deposit ledger 2473, c. 8, AS, AST. Used with permission.

Figure 2. Total amount and number of outstanding loans at the end of year (1747–1767).

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on data from deposit ledger 2473, AS, AST.

The deposit book—combined with main ledgers and other business papers—provides a wealth of information on loans that helps identify the Salvadori role in the local credit market and covers the type of credit instrument, size, expected maturity (if available), actual duration, and interest rate.Footnote 35

Of all the loans made, three out of five were nonnotarized transactions (Table 1). They were usually backed by an obligo—a private IOU in which the borrower promised to pay a specified sum of money within a specified period and at a fixed rate of interest—that was returned to the borrower or the person paying on the borrower’s behalf when the loan was repaid.Footnote 36 Only occasionally was a guarantee from a third person or the signature of witnesses required in addition to the borrower’s personal bond. In contrast, notarized loans took the form of scritto di credito (written credit), which consisted of a loan made for a specified period of time and secured by personal surety, real estate, or all of the borrower’s assets, present and future.Footnote 37 The credit instruments used by Salvadori were thus different from those employed by pawn banks and, to some extent, by nonspecialized credit institutions. We find almost no mention of pawn loans or of redeemable sales and other types of mortgage credit such as censi, which were widely used by local ospedali, along with scritti di credito.Footnote 38

Table 1. Features of loans recorded in the deposit ledger

Source: Compiled by the authors based on research database. *Data concern loans for which a fixed duration is specified.

Censi had become particularly widespread in Central and Northern Italy during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 39 The most common annuity contract was the census consignativus, which had been legalized with the issuance of Pope Pious V’s bull Cum onus (1569). With this type of contract, the debtor borrowed a sum of money by securing the loan with real estate and was free to repay the loan at any time; thus, the loan duration was not specified, but usually extended into the long-term. To comply with usury laws, the contract had to be drawn up by a notary, the real estate had to consist of income-producing property, and the interest rate could not exceed the legal ceiling. The redeemable sale, called compra cum recupera, had traditionally been used to disguise an interest-bearing loan. Under this contract, the borrower sold a piece of real estate in exchange for a sum of money, usually for a fixed period, and could buy the property back on the condition that the loan was repaid at maturity.Footnote 40

Comparing the Salvadori loan portfolio with that of other private lenders studied in the literature, we find both similarities and differences. Merchants in sixteenth-century Antwerp and wealthy farmers in nineteenth-century rural Sweden had in common with the Salvadori an extensive use of private IOUs (or promissory notes), although the Salvadori portfolio also included a considerable amount of notarized debt.Footnote 41 In contrast, we do not find evidence of short-term credit backed by securities, as in the Low Countries, nor do we find extensive use of mortgages in the form of perpetual annuities, as documented for some merchant-planters in the British Atlantic.Footnote 42

The loan amount was extremely variable, ranging from 42 florins to about 14,000 florins, with a mean of 1,100 and a median of 415, implying that borrowers had relatively large financial needs.Footnote 43 Because the loans were frequently renewed, we find substantial differences between expected and actual maturities. Nearly 60 percent of loans with a specified term (about two-thirds of all loans) were supposed to last up to two years, and seven years was the agreed-upon maximum term; however, less than 30 percent of all loans matured before two years, and more than half of the loans lasted longer than seven years, with an effective maximum term of more than fifty years.Footnote 44

There were no significant differences in the interest rates charged on loans. It is worth noting that interest-bearing loans were no longer stigmatized in the eighteenth century, and restrictions on usury took the form of a legal interest ceiling set by law or custom.Footnote 45 In the prince-bishopric of Trento, as elsewhere in Europe, the legal interest rate was set at 5 percent by midcentury,Footnote 46 but exceptions were made for irredeemable annuity contracts secured by real estate and for loans granted by merchants attending the Bolzano fairs, for which an interest rate of 6 percent was allowed.Footnote 47 Salvadori fully met the legal requirements by charging 5 percent on most loans, and interest was even lower for some debts dating back to the 1730s (when the legal interest was lower); some loans granted to relatives were charged at 4 percent to 4.5 percent. Only in one case did the interest drop to 3 percent: a debt originated by the sale of a piece of land with delayed payment. The uniformity of the interest rates charged confirms the idea suggested by Hoffman and colleagues of a “priceless market.”Footnote 48 Indeed, when dealing with debt made riskier by a lack of information about the borrower or the size of the loan, Salvadori did not charge a risk premium, which was limited by the legal cap, but rather sought to make the loan safer by asking for additional collateral and/or entering into a notarized transaction. This contrasts sharply with Puttevils’s findings for sixteenth-century Antwerp, where merchants’ ledgers show a wide range of variations in interest rates dependent on the borrower and the duration of the loan.Footnote 49

Only in a few cases—all concerning loans to borrowers operating in the silk sector—did Salvadori take advantage of the opportunity granted to merchants who participated in the Bolzano fairs, applying an interest rate of 6 percent. This privilege may have been intended not to discourage lending by merchants who would otherwise have received higher returns by lending through depositi di fiera or dépôts en foire (fair deposits), a common means of investing excess liquidity at fairs.Footnote 50 These were short-term loans granted through a bill of exchange until the next fair (i.e., for three months) and could be renewed. In the eighteenth century, they yielded up to 1.5 percent interest on a quarterly basis, but the Salvadori fair books show that this was the exception rather than the rule; the quarterly interest rate was usually 1.25 percent, and sometimes 1 percent.Footnote 51 Fair deposits possibly yielded equal or less interest than loans in the prince-bishopric, but they had the advantage of greater liquidity because it was easier to raise or employ funds at fairs, where a system of brokers facilitated the transfer of information between merchants.Footnote 52

Salvadori resorted more frequently to fair deposits in the 1750s; and financial transactions at fairs intensified further in the 1760s, when increased investment in the silk business exacerbated seasonal fluctuations in the firm’s finances, requiring a more flexible means of investing excess liquidity. A huge amount of money was required each June to purchase cocoons for processing into raw and thrown silk, which was then sold to foreign correspondents with a six-month delay in payment. Fair deposits must have proven the most suitable instrument for short-term investment. Combined with the lowering of the legal interest rate in the bishopric, this must have contributed to making local deposits less attractive, helping to explain the decline in loans recorded in the deposit ledger.Footnote 53

In terms of size, duration, and interest rate, the Salvadori loans show much higher values than those issued by the pawn bank—which catered to poor people in need of small amounts of money and wealthy clients in temporary distress—thus highlighting a complementarity of their lending activities. According to the statutes of the pawn bank, the amount of a loan could not exceed 90 florins, while larger loans were allowed only under certain conditions and with prior authorization; in most cases, however, the size of the loan was probably much smaller. Available data for the 1790s prove that the loan amount usually did not exceed 4 florins—the two-week income of an unskilled male laborer. As for the interest rate, in the 1740s it was 1.66 percent for loans up to 18 florins, and 2.5 percent for larger loans. The maximum term was two years, after which the bank could dispose of movable property received as collateral.Footnote 54 On the other hand, the Salvadori lending activity is more like the operation of local ospedali, which advanced larger sums at higher interest rates for longer periods of time.Footnote 55

The Social Dimension of Credit

To investigate the social dimension of credit, it is useful to look at the features of actors in terms of location and type of relationship with Salvadori. Most of the lending activity documented in the deposit ledger took place within the prince-bishopric: half the number of loans and two-thirds of the total amount went to borrowers from Trento and its immediate surroundings. Most of the remaining debts were owed by debtors from other localities in the principality, especially in Calliano, Pergine, and Mori, where the Salvadori family had business agents and/or family contacts (Table 2). These connections facilitated access to information about debtors, who sometimes were family relatives or firm agents, thus lessening the impact of geographic distance. Only a small number of loans were made to foreign borrowers, mainly in neighboring Tyrol.

Table 2. Distribution of loans according to borrower features

Source: Compiled by the authors based on research database.

A large, diverse group of borrowers were involved and classified according to the strength of their relationship with the Salvadori family and their social standing. We found relationship strength to be high for relatives, business associates, business agents, and employees; average for borrowers with accounts in the main ledger or with evidence of repeated contact; and low for all others.Footnote 56 What emerges is that only one in six loans went to people with whom the Salvadori family had a close relationship but they accounted for almost a third of the loan volume: six went to Giacomo Gottardelli of Mori, a vicario (bishop’s official), and four loans to Dr. Francesco Antonio Carli of Pergine, and both men were married to Valentino Salvadori’s daughters.Footnote 57 The marriage to Carli consolidated the bond already established between the two families in previous decades and may justify the better conditions applied on two of his loans, from a normal interest rate of 5 percent to 4.5 percent. That different terms were applied to the same borrower suggests a relevance of the loan size and purpose. The low-interest loans did not exceed 500 florins, while the higher interest loans were for 1,000 and 1,300 florins, and, as noted in the ledger, the largest sum was intended for silk manufacture. Evidence scattered throughout the deposit ledger shows that when a sum of money was to be invested in the silk business, Salvadori felt entitled to demand a higher remuneration.

Along with the circle of relatives, borrowers with strong ties included the agents and employees of the Salvadori firm, including the supervisor of silk manufacturing in Trento, agents in Calliano, and the manager of the retail store in Pergine.Footnote 58 Two small amounts were loaned to the family that managed a farm owned by the Salvadori family on a hill above Trento, and another to an employee for money received in excess of his salary.

Compared with borrowers with strong ties, those who had recurring relationships with the Salvadori overall borrowed more frequently, but the total value of loans they received was lower. These included relationships with merchants and petty traders, shippers, artisans, professionals, silk producers, clerics from the lower and upper ranks of society, and aristocrats. Loans to actors without regular contacts were higher in both florin amount and number of loans, but this can be easily explained if we consider that business correspondents had an open account in the firm’s main ledger, so that they usually benefited from interest-free overdrafts.

In terms of actors’ standing in the social milieu, we have a distinct category with all institutions and collective bodies, including the magistrato consolare (city council), the Tyrolean government, local churches, and communities. Two public-private partnerships established to foster silk manufacturing are also classified among institutions because of the prominent role of the urban government. We divided all other actors into three groups defined in relation to the social position of the Salvadori family.Footnote 59 Thus, we identified an upper social group comprising members of the local elite (nobles and patricians), an intermediate group consisting of those with a similar social position (i.e., merchants and professionals such as notaries and physicians), and a lower social group comprising small landowners, local shopkeepers, artisans, peasants, wage earners, and those about whom information is not available. The members of the third group, defined as such, did not necessarily belong to the lowest social stratum in absolute terms but were simply of a lower social level than the Salvadori family.

This classification shows that some of the loans made to institutional borrowers weighed heavily on the firm’s credit portfolio. As we shall show, the most significant were those to the City of Trento and to public-private partnerships, but Salvadori did not refrain from supporting other local and superior authorities. For example, the village of Calliano took out three notarized loans for a total of 850 florins, and the Tyrol Chamber in Innsbruck borrowed 1,500 florins in 1741 destined for Maria Theresa of Habsburg, at that time hard-pressed by the financial needs of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748).Footnote 60 Nonetheless, it was the upper class that borrowed the highest amounts, with the noble Wolkenstein family borrowing some 10,000 florins, and the Crivelli family almost twice that amount, while the lower social group was more prominent in terms of the number of loans. Overall, transactions with borrowers from the same social group as the Salvadori family, or “horizontal” credit relationships, approached one-quarter of loans by number and value, while “vertical” credit relationships predominated, highlighting the importance of loans that crossed social boundaries.

This varied composition of participants is even more evident when we look at the “extended” credit network, which includes all the actors with whom Salvadori came into contact in their lending activities, such as guarantors, those related to the origination of the loan, those who played a role in repayment, and persons mentioned in connection with the credit transactions such as witnesses, agents for Salvadori, and members of the borrowing companies. In addition to 104 borrowers and 19 notaries, dozens of other actors were involved, sometimes in different roles (Table 3). People other than borrowers and notaries appear in two-thirds of the loans, with a notable difference depending on the type of credit instrument: four-fifths of notarial loans have other actors mentioned, compared to just over half of nonnotarized loans. All of these actors formed a “chain of trust and information” that provides a snapshot of local society to which we can apply social network analysis (SNA) to identify key figures.

Table 3. Number of actors and frequency of citation

Source: Compiled by the authors based on research database. *The total number of actors cited is smaller than the sum of previous numbers (253) because of multiple citations of the same actors with different roles. **The total number of citations is smaller than the sum of previous numbers (401) because actors associated with the same loan but in two separate roles have been counted as one citation.

SNA is now an established methodology in the analysis of data from historical archives.Footnote 61 This technique is useful for describing and evaluating the role of social relationships in economic decisions and behaviors, and has gained momentum even among economic historians interested in investigating past commercial and financial networks.Footnote 62 Ego-networks are often used to visualize and describe the structure and evolution of a principal actor’s connections. However, to explore the Salvadori credit network, we used a different approach; instead of focusing on the connections between the lender and the borrowers, we analyzed the links between the loans (as an expression of the Salvadori financial and social commitment) and the actors involved in the transaction. As mentioned above, we consider not only borrowers and notaries but all actors involved.Footnote 63

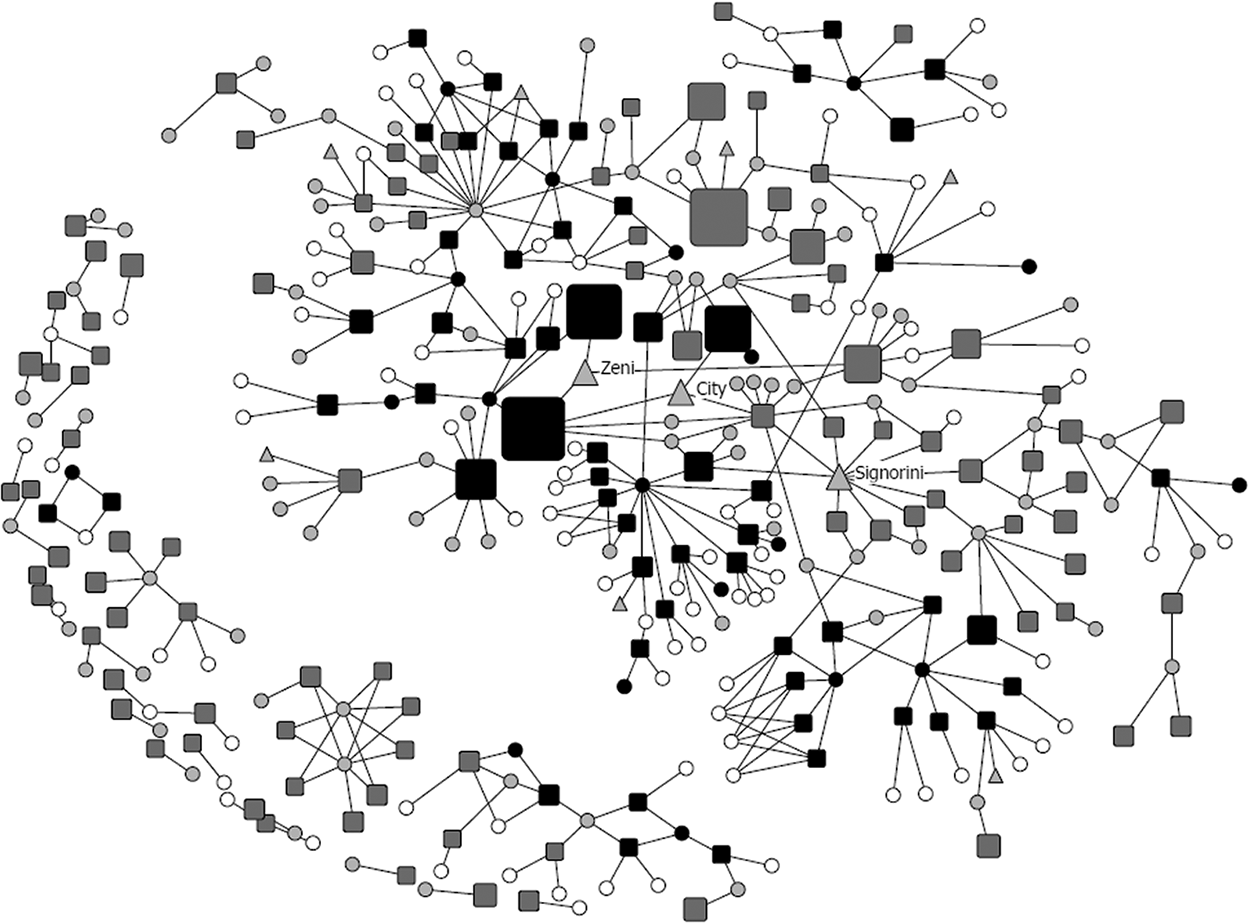

The structure of this “extended” network is characterized by a number of isolated components at the periphery and a core component with particularly dense ties as a result of the participation of multiple actors in the same transactions (Figure 3). The participation of actors from the lower social group (white dots) is frequent in all components, but if we apply SNA techniques,Footnote 64 we find that they are not among the most important actors for centrality (Table 4). We do not even find borrowers who are relevant in terms of citations and for their membership in the upper group (these include, for example, Giacomo Gottardelli, mentioned above, and Count Antonio Wolkenstein, who received seven loans for over 2,000 florins).

Figure 3. The extended credit network.

Source: Elaborated by the authors. Squares are loans (black for notarized loans, gray for nonnotarized loans), square size is based on loan amount; triangles are institutions; circles are other actors (white for actors of lower social standing than Salvadori; gray for actors of same or higher social standing; black for notaries).

Table 4. Centrality position of top 10 actors

Source: Compiled by the authors based on research database.

To identify the top actors by centrality position, we use a combination of centrality measures providing different information about the actors’ relevance. For this part of the analysis, we used the 1-mode weighted actors-by-actors matrix. Degree centrality reflects the number of ties an actor has, which depends on the number of actors involved in the same transactions; betweenness centrality represents an actor’s control and influence over the network related to position among nodes, while 2-local eigenvector centrality signals an actor’s connection with the most relevant nodes.

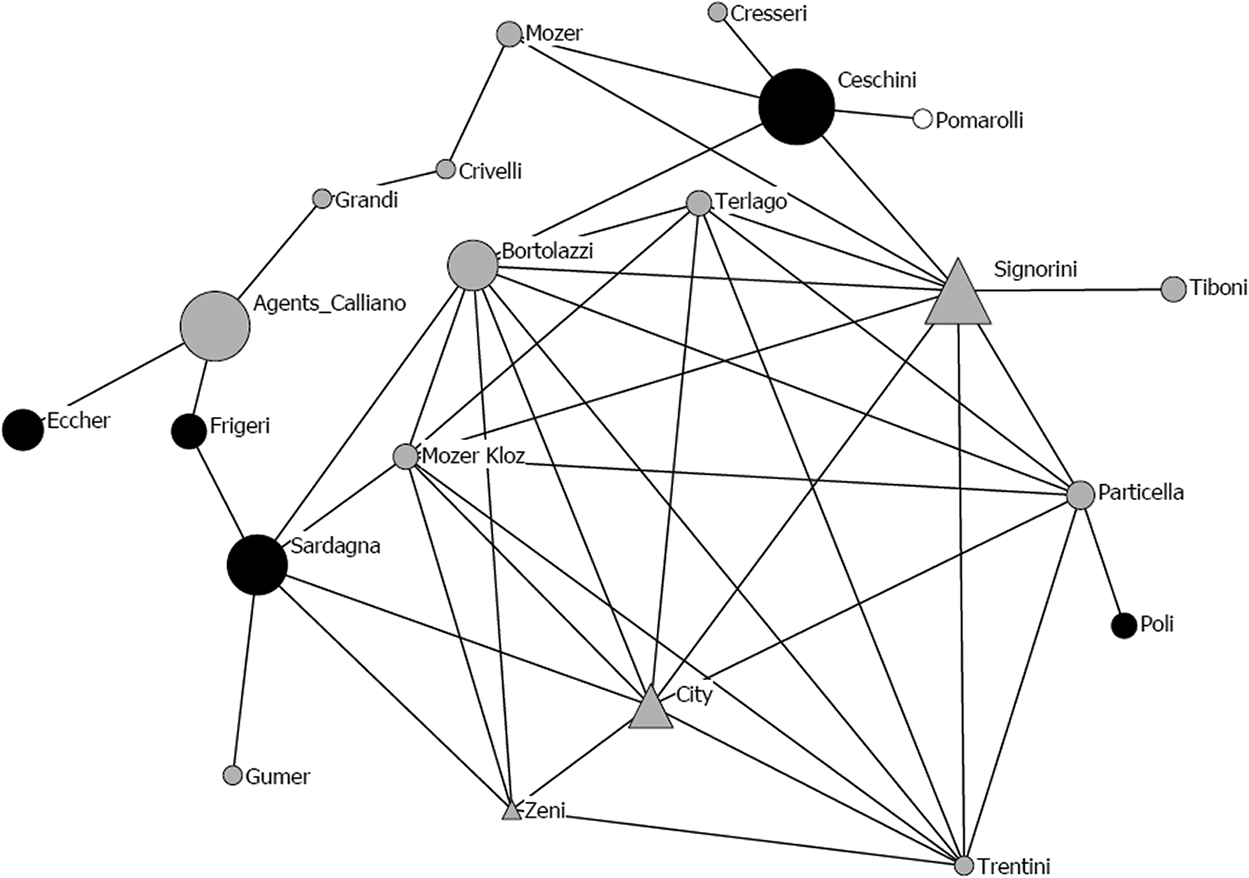

Focusing on a select group of actors with the highest centrality according to the three dimensions, there appears to be a dense network of ties linking important institutions—the Trento City Council and the two public-private partnerships, Signorini & Co. and Zeni & Co.—with prominent patricians (Bortolazzi, Terlago, and Particella) and merchants (Trentini & Co. and Mozer, Kloz & Co.) (Figure 4). The Salvadori themselves appear disguised in the network through their agents in Calliano and as Mozer heirs, who participated as such in Mozer, Kloz & Co. Several notaries are also key figures; all notaries who appear at the center of the network were trusted notaries of the Salvadori family. The prominence of members of the political and economic elite in the network core corresponds to some extent to what McLean and Gondal found in their study of interpersonal credit ties among elite households in Renaissance Florence. Interestingly, they find no mediation by notaries,Footnote 65 even though notaries routinely drafted loan documents by manipulating formal contracts to conceal illegal interest payments. As Goldthwaite argues, however, these notarized loans were mostly for small amounts, since, by about 1300, “businesses had replaced the notary with their own account books as the official record of larger credit transactions.”Footnote 66 Similar to Shaw’s finding for Venice, the core composition of the Salvadori network supports the idea of a “network of patronage and favour,” in which trusted notaries were an integral component.Footnote 67

Figure 4. Core of the credit network with relevant actors.

Source: Elaborated by the authors. Black circles are notaries; gray circles are actors other than notaries, upper and middle social standing; white circles are actors with a lower social standing; triangles are institutions. Size of nodes is based on degree centrality. Two actors have a tie when they are linked to the same credit transaction.

Among the key figures, we find a small circle of borrowers with strong ties to the Salvadori family, including institutions and members of the upper class—the City, its capoconsole (chief consul), and the two public-private companies—with the Salvadori firm as a partner. Loans to this group were few but amounted to no less than 39,000 florins.

It is extremely difficult to distinguish the role played in the granting of the loan by purely economic-financial considerations as opposed to social or political motivations. Because we lack direct evidence, we can only deduce from the choices and behaviors of the Salvadori family. One can reasonably assume that for a family in rapid economic and social ascendancy in the prince-bishopric, it was important to establish appropriate connections with the local political and social elite. The main authorities—the prince-bishop and his courtly council, the cathedral chapter, and the city council—were dominated by a small group of families belonging to the old nobility and patriciate. This closed local elite hindered homines novi (new men) access to power, and the Salvadori themselves were no exception.Footnote 68 Although they had been living in Trento since the 1660s and had gained citizenship in 1729, it was not until the end of the century that they were elected to the Trento City Council, thus gaining access to the patriciate. This happened only after acknowledgment by the prince-bishop of the title of Barons of the Holy Roman Empire, granted to the family in 1766 by Emperor Joseph II.Footnote 69

The attention to serving the interests of the governing elite is exemplified by the credit extended to the city and the head of its council. In 1751, Salvadori granted a notarized loan of 8,500 florins to the urban government at 5 percent interest, to be repaid at will with six-months’ notice. The same year, Chief Consul Sigismondo Adamo Terlago borrowed two sums for a total of 1,400 florins on similar terms but secured by a privately written IOU.Footnote 70 In both cases, the lack of a fixed repayment date is indicative of a patron-client relationship characterized by mutual obligations between the parties.Footnote 71 This is further supported by the fact that when Terlago repaid the loans two months later, the Salvadori firm exempted him from paying the interest amount of 10 florins and a half per gratitudine (as an expression of their gratitude to him).Footnote 72 We found another ten examples of open-ended loans, mostly granted to borrowers strongly connected to Salvadori and/or belonging to the highest ranks of local society. This was also the case of the loan to Giovanni Giuseppe Gentilotti, canon of the cathedral chapter, who in 1734 borrowed 1,260 florins against his obligo and repaid the sum in 1765.Footnote 73

The largest amount of capital went, however, to one of the two public-private partnerships promoted by the city council to foster the silk business. Both were limited partnerships financed by the urban government and a few wealthy citizens as capitalist partners, and managed by another partner who contributed his labor and gave the firm its name. The first company, Giuseppe Signorini & Co., was founded in 1745 and had among its financiers the aforementioned chief consul; some patrician families; and the most notable Trento merchants, including the Salvadori family and Mozer, Kloz & Co. Salvadori contributed 1,500 florins directly and 500 florins on behalf of Francesco Mozer, who remained a “hidden” investor. Although the sums were recorded in the deposit book, they were risk capital remunerated with a share of the profits. Unfortunately, the Salvadori family lost part of their investment, but they were able to profit from the silk commissions from the Signorini firm, their most important client in the late 1740s. Following the death of Giuseppe Signorini, the Trento City Council promoted a new public-private partnership, Luca Zeni & Co., in 1754: Salvadori contributed a sum of 14,000 florins as risk capital and a deposit of around 12,000 florins with an interest of 6 percent. Within a few years, the partnership ceased to make a profit and, in 1760, Salvadori withdrew from it. The interest-bearing deposit was repaid, but as far as can be judged from the deposit book, their risk capital was not recovered. The financial losses must have been offset by gains from the sale of silk, although the “social rewards” of strengthening relations with the urban ruling elite must also be considered when evaluating the transaction. The withdrawal from the partnership coincided with a change in the commercial strategies of the Salvadori firm that greatly increased shipments of silk to foreign customers.Footnote 74

Among the core figures in the Salvadori network were Dr. Antonio Crivelli and Giacomo Antonio Bortolazzi, both of whom belonged to the richest and most powerful families in Trento. The Salvadori lent 12,000 florins to each in the mid-1730s, in gold coins and through remittances to third parties. The interest rate was fixed at 4 percent, and later increased to 5 percent when credit market conditions changed. Both borrowers could pay in installments, provided they gave three-months’ notice—sufficient time for Salvadori to find alternatives to reinvest such large sums of money. Despite an agreed duration of six to seven years, both credit relationships lasted for much longer periods, with Crivelli’s debt lasting the longest. Bortolazzi’s debt was partially reduced and finally transferred in 1749 to Signorini & Co.; Crivelli’s debt passed to his heirs and was discharged in 1790.Footnote 75

It should be kept in mind, however, that all the borrowers mentioned above were relevant not merely as recipients of loans but also as the backbone of the credit activity because of their position in the network. Even so, we also find nonborrowing figures as core participants, such as the Venetian merchant-banker Antonio Maria Tiboni, who was responsible for receiving or making payments on behalf of Salvadori and their borrowers; and Councillor Particella, a member of the Trento Courtly Council, who intervened as an arbitrator in the settlement of a debt owed by an insolvent patrician to his debtors, including Salvadori.Footnote 76

The Role of Notaries

Among the nineteen different notaries who drafted loan agreements for Salvadori, three appear most often in Trento: there was Ceschini (twelve loans), Poli & Son (seven loans), and Sardagna (six loans), who all also drafted wills, marriage contracts, and other important deeds for the family. In Calliano, the most active notaries were Eccher (six loans) and Forrer (six loans) (Figure 5). Four of these notaries appear among the core in the Salvadori network.

Figure 5. The Salvadori credit network, borrowers and notaries only.

Source: Elaborated by the authors. Squares are loans (black for notarized loans, gray for nonnotarized loans), square size is based on loan amount; triangles are borrowing institutions; circles are other actors (white for borrowers of lower social standing than Salvadori; gray for borrowers of same or higher social standing; black for notaries). Included are borrower ties to transactions in which they participated in different roles.

Although most loans were not authenticated, notaries played an important function in supporting the Salvadori lending activities. But if, as in sixteenth-century Antwerp, merchants preferred not to spend time and money on the public registration of contracts,Footnote 77 then the questions are: How can we explain the almost 40 percent of debts recorded at a notary? Why use the notary for some loans but private agreements for others? Is it true, as the literature suggests, that the greater the social distance, the more frequent notarial intervention was required to compensate for reduced trust and information asymmetries?Footnote 78

In comparing the main features of notarized and nonnotarized loans granted by Salvadori, we find no meaningful differences (see Table 1). In contrast to the data for rural France, where Dermineur found that nonnotarized loans were used for smaller amounts,Footnote 79 we find no such evidence. The values of the first, second and third quartiles are lower for notarial loans; the average amount appears higher for notarial loans only because of two large loans with the Zeni partnership. In fact, notarial loans were used when large amounts were involved. For example, Salvadori granted several nonnotarized loans to Count Antonio Wolkenstein and Count Gaudenzio Wolkenstein, in amounts between 100 and 1,000 florins, but a notarized loan of 7,500 florins granted jointly to the counts.

The loan of 12,000 florins to Bortolazzi was also authenticated. At the time of the loan, the Bortolazzi family had amassed a fortune as merchants and had recently been ennobled. Giacomo Antonio Bortolazzi was still engaged in the manufacture and trade of silk, and would later contribute an interest-bearing deposit to Zeni & Co. His real estate holdings in the urban district made him Trento’s wealthiest citizen;Footnote 80 nonetheless, Salvadori stipulated a notarized loan with him. However, that the size of the loan was not the most significant factor is documented by the fact that Salvadori accepted an obligo from Crivelli for a loan of equal value.Footnote 81 What we can deduct from this is that Salvadori counted on the considerable reputation enjoyed by Crivelli, an old Trento family whose members had been elected to the city council for centuries.Footnote 82

Data on loan duration suggest that Salvadori preferred to go to a notary for long-term loans. For example, there were more notarized loans that were expected to last longer than two years. Even so, it was much more common in nonnotarized transactions to have an unlimited duration. In terms of actual duration, notarial loans lasted longer on average, but there was no significant difference in maximum duration, which exceeded fifty years for both notarized and nonnotarized credit. Therefore, the size and duration of the loans cannot provide conclusive evidence as to the reasons for using different credit instruments. The credit instrument used was sometimes related to the nature of the transaction and the borrower. When it came to property transfers on real estate, a notary certified the loan, and the same was true for loans to institutions or women. There are only four female borrowers in our dataset, three of whom were widows. Combined, they took five loans and in only one case—a loan granted to a widowed noblewoman—did the Salvadori family not use a notary.

In all other cases, we must consider the lender-borrower relationship to explain the type of credit instrument. It is worth noting that, although private writs were allowed as legal evidence in court cases in Trentino-Tyrol,Footnote 83 and notarized loans per se did not give the creditor any priority right over the debtor’s assets,Footnote 84 the creditor had a preferential claim when a specific piece of real estate was mortgaged, and public registration made contracts more easily enforceable since notarized loans benefited from a simplified procedure. This also applied to privately written obligations signed by three witnesses (which is not the case here, however), as established by the statutes of the City of Trento, which applied to the entire territory of the bishopric.Footnote 85 Thus, the greater the uncertainty and the less reliable the counterparty, the greater the incentive to register with a notary.

By examining notarized and nonnotarized loans separately, we observe some differences in the distribution of loans according to the distance of borrowers from lenders (Table 5). Information on location suggests that the Salvadori preference for nonnotarial instruments was weaker when it came to loans for actors outside the prince-bishopric. Contrarily, it did not matter much whether the borrower lived in the area around Trento or in other locations within the bishopric, perhaps because in some locations where Salvadori engaged in lending more frequently, they had agents or relatives who reduced the impact of geographic distance. Instead, both the social standing of the borrower and the strength of the relationship with the Salvadori family seem much more important. They made little use of notaries for loans to borrowers of similar social level; the preference for notaries was strongest when loans were made to borrowers of lower social position, but notarial loans were not the preferred instrument in the case of nobles and patricians. There may be several explanations for this. First, families from the higher ranks of society were known to have larger assets and thus a greater ability to meet their obligations; second, the extra-economic motivations for starting a credit relationship with members of the political elite could outweigh the interest in securing the debt; and third, taking an aristocrat or patrician to a notary would have meant a lack of trust unless the loan was of a significant amount.

Table 5. Distribution of loans according to borrower features: notarized and nonnotarized loans compared

Source: Compiled by the authors based on research database.

For all loans to borrowers with strong ties, the Salvadori firm was satisfied with an obligo, with two exceptions. One concerns the loan of 42 florins granted to an employee for money received in excess of his wage, for which a notary drew up the contract; another is the first loan granted to Giacomo Gottardelli. In this case, Gottardelli’s recent entry into the family circle, which took place in 1747 with his marriage to Caterina Salvadori,Footnote 86 and the size of the 4,000 florin loan possibly explain why the sum received in July 1747 was guaranteed by a notarial deed, unlike subsequent loans not exceeding 1,000 florins each.

Similarly, financial transactions with borrowers who had recurring relationships with Salvadori were usually not notarized, whereas notarization was more common for loan agreements with borrowers with weak ties. Nonetheless, those with weak relationships did receive a substantial number of loans and, not surprisingly, such borrowers mostly belonged to the lower classes.

The joint analysis of the two main indicators of social proximity—namely, social standing and strength of tie—helps to better investigate the role of trust. Among borrowers who belonged to lower social groups and had weak relationship status, we find a particularly high incidence of notarial loans (Table 6). However, a reputation effect and higher levels of trust appear as we move from lower class to middle-high class, and as the relationship status moves from weak to medium to strong. Analysis of the Salvadori loans thus confirms that the reputation gained through repeated exchanges or kinship reduced the need for the formal guarantees provided by a notarial deed. Significantly, borrowers with similar or higher social standing and a medium or strong relationship with the family received nonnotarized loans, with the exception of the aforementioned case of Gottardelli.

Table 6. Number of notarized loans for borrower social group and share of notarized loans on total loans granted to the group

Source: Compiled by the authors based on research database.

Therefore, social distance mattered. Compared to the Parisian credit market, information flowed more easily in a smaller community, but social distance—the result of the societal hierarchical structure and weak relationships among people from different social groups—made notarial intervention important to expand the reach of credit to the lower socioeconomic strata.

Concluding Remarks

The Salvadori case shows how in a region somewhat distant from the most dynamic commercial centers, merchant liquidity “trickled down” to the local economy and society and contributed to vitalizing the credit market. The Salvadori firm met the financial needs of various people in need of credit, including merchants, artisans, professionals, aristocrats and patricians, clergymen, widows, and local institutions. The characteristics of loans show that their lending activity was complementary to that of pawn banks, but more like that of the local ospedali. While the monte di pietà catered to poor people in need of small sums of money and wealthy clients in temporary distress, Salvadori advanced larger sums for longer periods at higher interest rates, albeit within the legal ceiling. Vertical relationships far outweighed horizontal relationships in the Salvadori loan portfolio; more precisely, upward relationships were prevalent in the amount of loans while downward relationships were predominant in the number of loans. Although people from lower socioeconomic echelons accounted for a smaller share of the loan volume, many of them turned to the Salvadori firm to meet their financial needs.

The composition of the loan portfolio suggests that, to understand the lending practices of these merchant-bankers, we must apply “an analytic framework that takes into account both the economic rationale of doing business and the broader societal context within which this occurred.”Footnote 87 Indeed, a combination of economic rationality and social motivations appears to have guided this family’s financial strategies, revealing an overlap and tension among commercial interests and social constraints and aspirations. The evidence of the firm’s lending activities supports Fontaine’s thesis that debt portfolios were influenced by the merchants’ obligations to their relatives and close associates while, on the other hand, their financing strategies must have supported their aspirations for upward mobility as the large share of the volume of loans to local institutions and patricians seems to indicate.Footnote 88 Although it is extremely difficult to disentangle the economic and social underpinnings of credit, the loans presumably helped the Salvadori family strengthen their ties to the narrow oligarchy that controlled urban government and paved the way for their eventual acceptance into the local governing elite.

The Salvadori firm’s “extended” credit network provides a portrait of the social structure of the local community. Applying SNA to identify key figures, we find that members of the local commercial and political elite were prominent figures in terms of position of centrality and influence, together with a few trusted notaries. This is in line with Shaw’s finding for Venice, which highlights the prevalence of relationships of power and favor over a system of market exchange based on impersonal relationships.Footnote 89 We have no direct evidence that notaries really acted as brokers, but they certainly played an important function in reducing uncertainty and making debts more easily enforceable when dealing with less reputable debtors. The mixture of formal and informal agreements in the Salvadori loan portfolio supports the thesis that loans made outside of notarial circuits contributed to a large share of the credit market, and makes our results similar to those reached for rural France. Although the Trento district had a larger and less socially homogeneous population than the rural villages investigated by Dermineur, in both cases information circulated more easily than in the Parisian credit market, and lower information asymmetries reduced the need to resort to notaries.Footnote 90

Nonetheless, social distance—the result of the societal hierarchical structure and weak relationships among people from different social groups—made notarial intervention important to expand the reach of credit to the lower socioeconomic strata. Through notarial credit, the merchants’ liquidity reached those belonging to the lower echelons of society, most of whom had weak ties to the Salvadori family. In contrast, taking a family member or business associate to the notary would have meant a lack of trust, and the same was true for aristocrats and patricians, unless recourse to a formal agreement was justified by the size of the loan.

Unquestionably, the Salvadori deposit ledger provides only a snapshot of the local credit market from the perspective of one merchant-banker family, perhaps emphasizing the importance of some actors and types of credit instruments while underestimating or neglecting that of others. Expanding the research to include other types of sources, such as probate inventories, could help shed further light on the workings of the credit market in this “less-developed” economy.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Andrea Bonoldi, Marina Garbellotti, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. We have presented earlier drafts of our work at the Paul Bairoch Institute of Economic History in Geneva, the European Conference on Social Networks 2017 in Mainz, the SISEC 2020 conference in Turin, and the HNR+ResHist Conference 2021. We are grateful to all the participants for their comments. The usual disclaimer applies.