In the age of Donald Trump, women opposed to his presidency mounted a large-scale political resistance. From the historic Women's March held just one day after his inauguration in January 2017 to the record number of largely Democratic women who sought political office in 2018, women's activism in politics appeared to reach a record high in American political history. This apparent spike of political engagement among American women, especially those on the political left, spanned generations. For instance, studies show that among Generation Z, defined as those Americans born after 1996, young women were more engaged and enthusiastic about politics than young men (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2020; PRRI 2018), a pattern that defies historical norms (see, e.g., Verba, Burns, and Schlozman Reference Verba, Burns and Schlozman1997). Other studies also note that young women's voting turnout surged in 2018 compared with the 2014 midterm elections (CIRCLE 2020). One possible explanation for this apparent surge of political engagement among young women in Generation Z may involve the gendered role model effect.

Previous studies suggest that when female citizens are exposed to high-profile women running for or serving in political office, they are more engaged in politics and more likely to envision themselves as political actors (Atkeson Reference Atkeson2003; Atkeston and Carillo Reference Atkeson and Carrillo2007; Burns, Schlozman and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Liu and Banaszak Reference Liu and Banaszak2017). This role model effect may be especially pronounced and present for young women: awareness of women politicians can boost young women's intention to participate in politics, increase their attention to and discussion about politics, and make them more optimistic about democracy (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006, Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2020; Mariani, Marshall, and Mathews-Schultz Reference Mariani, Marshall and Lanethea Mathews-Schultz2015; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2019). Though these studies typically include older women as political role models, there is no reason to think that this effect is limited to older female role models. During the 2018 midterm elections, the media frequently highlighted the unprecedented number of younger women who ran for office, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, whose upset victory in her Democratic primary and savvy social media skills helped make her arguably the most famous newly elected member of Congress in 2019. The 2018 midterms saw the historic election of the first two Muslim American women, the first two Native American women, and the two youngest women to Congress (Zhou Reference Zhou2019). Record numbers of women, people of color, and LGBTQ candidates also won state legislative elections in 2018 (González-Ramírez Reference González-Ramírez2018), with Nevada becoming the first state to have a majority-female legislature in the United States. In short, one could make the case that in the United States, the public face of politics is becoming younger, more racially and ethnically diverse, and increasingly female. Empirically, however, the question remains whether seeing young women seeking political office has a gendered role model effect on Gen Z women when it comes to shaping their proclivity toward future political engagement. Moreover, we know little about whether seeing a larger diversity of candidates in terms of not just gender and age, but also race, will lead Gen Z women to express more intention to participate in politics.

Inspired by these two trends—the influx of more diverse and younger political women leaders and the apparent surge of Gen Z women's activism in American politics—we examine how exposure to young women and more diverse candidates running for office propels interest and engagement in politics among Generation Z women through a survey experiment. While Generation Z roughly encompasses young Americans born between 1997 and 2010, which in 2019—the year we conducted our study—represented Americans aged 9 to 22, our study focuses on Gen Z Americans between the ages of 18 and 22, the elder spectrum of Generation Z.Footnote 1 Notably, given that Gen Z is also the most diverse generation in terms of race and ethnicity (Dimock Reference Dimock2019), we consider how the demographic features of these young citizens interact with the demographic features of candidates to spur potential political activism. Our study exposes respondents to one of eight candidate treatments, all involving individuals running for state legislature but who differ based on age, race, and gender. Because respondents may infer partisanship from these characteristics, we label all the candidates in our experiments as Democrats.Footnote 2 We then ask them about their likelihood of future political engagement, ranging from less taxing forms, such as encouraging people to vote, following political news, discussing public affairs, or using social media for political purposes, to more demanding forms, such as attending a protest march or government meeting, volunteering for a campaign, or even running for office.

We find a somewhat complicated picture when it comes to the role model effect for young women in this generation. Among Gen Z women who strongly identify with their gender, seeing young women run for office does make them more interested in future political activity. However, this future mobilizing effect emerges for such women when they are exposed to all of the treatments involving young, minority, and female candidates, but not older white male candidates. And though all the politicians in the experiments are Democrats, we do not find that the effects are specific to Democrats but apply broadly to women high in gender identity. We found no such effects for either Gen Z men or among Gen Z women who do not strongly identify with their gender.

We show that the role model story among Gen Z women is not so much about age, gender, or race individually, as it is about seeing any politician who does not fit the stereotypical image of a political candidate (white, male, and somewhat older). As a result, we find that it is not a female role model effect per se, but rather a story about young women being motivated by the appearance of candidates who fit with the “coalition of the ascendant.”Footnote 3 Our findings are better situated within the group empathy literature and studies that find that exposure to more gendered and racially diverse political leaders can boost democratic legitimacy among citizens more broadly. These findings have important implications for the future of American politics, as they suggest that motivating a new generation of young women who strongly identify with their gender to get involved in politics has less to do with role models who represent them descriptively, and possibly more to do with recruiting slates of candidates that are generally more diverse than is common in American elections.

REPRESENTATION THEORY, THE ROLE MODEL EFFECT, AND GENDER IN THE UNITED STATES

The causal mechanism underlying the role model effect for women is multifaceted and hinges, in part, upon the nature of representation in government and politics. One form of representation in a democracy is descriptive representation, or the idea that those serving in or running for political office should closely match the citizenry in terms gender, race/ethnicity, or other traits (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). Some political theorists posit that historically lower levels of political engagement among women and racial minorities can be linked to low levels of external efficacy brought about by a lack of descriptive representation in government (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999). Relatedly, many scholars have noted that politicians who do not belong to one of these disadvantaged groups may not take their concerns as seriously (Atkeson Reference Atkeson2003; Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001), making these groups feel increasingly disaffected and alienated. By contrast, experimental research shows that when citizens are exposed to government bodies that are gender balanced—as opposed to all male—democratic legitimacy is enhanced among those citizens (Clayton, O'Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019), again reinforcing the importance of descriptive representation to political behavior.

Another facet of political representation theory is symbolic representation, which involves, in the words of political theorist Suzanne Dovi (Reference Dovi2007), “an emotional response” between the represented and the representative. As applied to women, having more women play prominent roles as political leaders and candidates signals to other women that the political system is receptive to their involvement despite men being overrepresented in those capacities. Both the descriptive and symbolic representational aspects of having more women in the public sphere signals to women that their involvement in the political system is welcome, legitimate, and important. It stands to reason, then, that seeing more women run for office may be inspiring to the political choices of Gen Z women given that the vast majority of political leaders remain men.

The connection between seeing more women as visible political leaders and increased political engagement has been demonstrated in a large number of studies that find that women who run for elected office or who serve as leaders in public office often spur women citizens to talk about and participate in politics more frequently (Atkeson Reference Atkeson2003; Burns, Schlozman and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Koch Reference Koch1997)—not just in the United States, but in other nations as well (Alexander and Jalalzai Reference Alexander and Jalalzai2020; Barnes and Burchard Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Gilardi Reference Gilardi2015; Liu and Banaszak Reference Liu and Banaszak2017; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007). Exposure to more women in elected and appointed positions also makes women more confident in the ability of other women to govern (Alexander Reference Alexander2012) and promotes higher values of external efficacy, or faith in democracy's ability to meet the needs of its citizenry, among women (Atkeson and Carillo Reference Atkeson and Carrillo2007). Similarly, research suggests that the role model effect applies for other underserved minorities in elected office, not just women. For instance, minority representation can boost political empowerment, knowledge, and voter turnout among minority groups such as Latinos (Barreto, Segura, and Woods Reference Barreto, Segura and Woods2004; Pantoja and Segura Reference Pantoja and Segura2003) and African Americans (Banducci, Donovan, and Karp Reference Banducci, Donovan and Karp2004; Bobo and Gilliam Reference Bobo and Gilliam1990; but see Gay Reference Gay2001).

This is not to say that there are no potential limitations on the role model effect. Some studies find that greater descriptive representation among candidates, at least when it comes to gender, does not necessarily increase intention to vote among women voters (Dolan Reference Dolan2006; Lawless Reference Lawless2004; Wolak Reference Wolak2015) or result in more participation in political campaigns among women (Lawless Reference Lawless2004)—though Wolak's (Reference Wolak2020) longitudinal analysis from 2006 to 2014 finds that living in districts with female representatives increases levels of political knowledge for both women and men. Other studies find that the role model effect is most powerful when situated within larger political contexts in which gender themes are prominent. For instance, Hansen (Reference Hansen1997) found that living in a congressional district in which women were on the ballot increased women's propensity to discuss politics during the so-called Year of the Woman in 1992, when a record number of women ran for Congress, but not in congressional elections in 1990 or 1994. There is also likely a novelty concern involved, as seeing the first high-profile woman win public office in their district or state may have a large effect on the political engagement of women initially; once women's participation in electoral politics becomes more commonplace, the effect of any new women entering the political arena on the political behavior of women citizens is likely to be minimal (Gilardi Reference Gilardi2015; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2017).

Considering the gendered role model effect on Gen Z women, we believe, merits examination for several reasons. First, examining the political behavior of younger Americans is especially crucial given that political socialization studies show that younger adults develop their participation and political habits in late adolescence and early adulthood (Denny and Doyle Reference Denny and Doyle2009; Michelson, Garcia Bedolla, and McConnell Reference Michelson, Bedolla and McConnell2009; Niemi and Jennings Reference Niemi and Jennings1991; Wattenberg Reference Wattenberg2015)—at the age when they are likely the most susceptible to a role model effect. Not surprisingly, then, the role model effect for women is greatest on adolescent girls and young women, both in the United States (Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006, 2017; Mariani, Marshall, and Mathews-Schultz Reference Mariani, Marshall and Lanethea Mathews-Schultz2015; Wolak and McDevitt Reference Wolak and McDevitt2011) and abroad (Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2007).

Second, although younger adults may be more receptive to socializing forces more generally than older adults, we believe a study that considers the unique circumstances impacting Generation Z is warranted. Given the rebirth of the women's movement after Trump's election and the record number of women who sought political office in 2018, which was highly touted in the media and included many candidates who ran with the express theme of promoting the inclusion of more women in politics (Hook Reference Hook2018), we believe that Gen Z women may be particularly susceptible to a gendered role model effect. Analyses conducted in wake of the historic 2018 midterm elections continue to show a powerful role model effect on girls. For instance, political scientists Christina Wolbrecht and David Campbell (Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2019) find that in districts that featured Democratic women candidates in 2018, their presence led to a more positive perception of American democracy among Republican and, especially, Democratic teenage girls. Notably, this effect was also present for Democratic boys, but led to more negative perceptions of democracy among Republican boys. There is no reason to suspect that older American women are somehow immune to these socializing events, particularly given the influx of women's participation in the larger #MeToo and Women's Movements that emerged in wake of Trump's election. However, given that the earlier work on role models tends to find its greatest impact is on younger women, we have chosen to isolate our analysis to Generation Z and urge future research to consider whether a gendered role model effect is present for all American women in the aftermath of the Trump presidency.

SOCIAL IDENTITY AND GROUP EMPATHY THEORY

A gendered role model effect may not impact all Gen Z women the same, however. For instance, Mariani, Marshall, and Mathews-Schultz (Reference Mariani, Marshall and Lanethea Mathews-Schultz2015) find that the role model effect is mitigated by party and ideology, with liberal and Democratic girls more prone to its effects. Although their work and several other studies consider partisanship to be a key moderator in the role model effect, we look instead at gender social identity. Social identity refers to a “subjective sense of belonging” to a particular group (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1981). This sense of belonging, however, requires that an individual feel a strong attachment to the group or community of people who share this identity. As Huddy (Reference Huddy2001) points out, members of a group who are high in social identity are motivated to advance that group's status. They are also more likely to draw a differentiation between members of the in-group and members of the out-group. One area in which gender relates to social identity concerns support for feminism, as strong gender affiliation among women leads them to be more supportive of feminist ideas while men strong in gender identity are less supportive of feminism, likely because of the threat concerns feminism raises regarding the place of males in society (Burn Reference Burn1996; Burn, Aboud, and Moyles Reference Burn, Aboud and Moyles2000).

Age or generational cohorts, in addition to gender, are also identified as a potentially meaningful category (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner and Worchel1986). Psychologists and organizational behavioralists find that common experiences among generations shaped through peers, media, and popular culture can imbue for some individuals a sense of belonging. In turn, individuals who find their generational cohort to be a salient identity may socially categorize themselves as distinct from individuals who hail from other generations (Van Rossem Reference Van Rossem2019; Lyons and Kuron Reference Lyons and Kuron2014). As applied to politics, for instance, Rouse and Ross (Reference Rouse and Ross2019) argue that millennials have their own unique political identity that stands apart from older generations, which, in turn, colors their public opinion. Regardless of whether the “Gen Z” label is meaningful to members of the generation, Gen Z has emerged as an important political group with characteristics that differentiate it from other age categories. And while, to our knowledge, there are no studies that consider whether Gen Z is responsive to seeing younger candidates run for political office, our study provides for that test by including treatment conditions of young candidates in our experiment.

Gender social identity may interact with age to shape the role model effect because individuals who do not feel a subjective sense of belonging to their gender or to their age cohort may be unlikely to care if a politician that they are evaluating is a member of the in-group or out-group. With respect to gender social identity, specifically, women who seek to advance the interests of those in their group should, however, be more motivated to engage in the political system when the slate of candidates reflect a greater diversity than normal. Plus, there may be reason to expect that this effect is present among many Gen Z women post-Trump and the #MeToo movement regardless of party, given that Wolbrecht and Campbell's (Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2019) study of the role model effect in congressional districts in 2018 found that its impact also reached GOP girls who lived in areas where Democratic women ran for office. At the same time, their analysis also showed that Republican boys actually had more negative attitudes toward democracy when exposed to more Democratic women candidates, which calls to mind earlier studies regarding linkages between gender identity and feminism. If this mechanism holds among Generation Z, we should find in our analysis that gender social identity may shape more positive views about future political engagement among Gen Z women high in gender identity, and potentially more negative views about such engagement among Gen Z men high in gender identity.

While Gen Z women high in gender social identity should respond more positively to women seeking public office, they may also respond positively to candidates belonging to other historically marginalized groups. Group empathy theory, as posited by Sirin, Valentino, and Villalobos (Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2016), argues that individuals who belong to one traditionally marginalized group will feel a stronger sense of connection to individuals who belong to a different traditionally marginalized group. As a result, group empathy can change the political behavior of individual group members and improve intergroup relationships. Relatedly, research by Harbin and Margolies (Reference Harbin and Margolies2020) finds that white individuals (both women and men) who identify as strong feminists are more open to perceiving racial discrimination. While Harbin and Margolies consider feminist identification, and not strength of gender identity, in their analyses, it is their finding that “certain subgroup identities can be associated with heightened awareness about the discrimination faced by other stigmatized groups” (3) that is relevant for our research here. Those who recognize historical inequality in one context are more likely to recognize it in other contexts and support efforts to address the problem. It is the shared acknowledgement of injustice among groups who have faced marginalization that appears to drive allyship.

While, to our knowledge, group empathy theory has not been applied to gender identity, we argue that its application in this situation may be particularly relevant for Gen Z women, who have been socialized politically at a time when concerns about lack of representation of both women and racial and ethnic minorities has become more commonplace in wake of Trump's election and the subsequent response of record numbers of women and minority candidates seeking office. Moreover, it is also important to remember that Generation Z is the most diverse generation in our nation's history: close to half of Gen Z Americans are nonwhite. Linking back to representation theory, as Jane Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge1999, 629) reminds us, the importance of descriptive representation in government lies not merely in visible characteristics such as gender and race—though these are important—but also in “shared experiences.” Thus, we argue that Gen Z women high in gender identity may be more motivated to engage in politics not only after being exposed female candidates, but also after exposure to candidates who do not fit the stereotype of the older, white man seeking public office.

We largely believe that Gen Z men will be unmoved by seeing men run for office, regardless of their gender identity. This is because men are already well represented in government, so seeing a man running for office is not especially noteworthy. Moreover, the strength of group identities is thought to center on a question of group threat (Ashforth and Mael Reference Ashforth and Mael1989; van Knippenberg Reference Van Knippenberg and Tajfel1984). There is the possibility that if Gen Z men high in gender identity perceive women running for office to threaten men's social status, a woman's presence on the ballot could spur participation among such men. Yet we view this as unlikely, as a single instance of a woman on the ballot is unlikely to generate a great deal of threat perception.

Thus, we are most interested in whether exposure to younger candidates, particularly younger female candidates, works to inspire Gen Z women to become more interested in political engagement, in essence asking whether there is an “AOC”-type effect in terms of inspiring Gen Z women to participate in politics.Footnote 4 Of course, exposure to younger candidates more generally may influence the political preferences of Gen Z Americans, both women and men, if they view younger groups as a more marginalized group in society—especially considering that most elected officials in this country are older. There is a theoretical possibility that exposure to younger candidates, who may be considered an outlying group in terms of typical political candidates, may motivate both Gen Z women and men to participate more in politics in the future as it shows Gen Z that politics is a more welcoming place for them; our study's design allows us to test for that possibility.

Our study applies scholarly literature concerning political activism, role models, social identity, and group empathy to the political behavior of Gen Z Americans, focusing on how exposure to fictional candidates running for state legislature who differ by age, gender, and race relates to the decisions of young women and men to participate in politics. With the present research, we ask three primary questions:

1. Does the greater visibility of young women running for political office encourage more political interest and more desire to engage in politics among young women high in gender identity?

2. Likewise, does it discourage such interest and intentions among young men or perhaps encourage more participation among Gen Z men high in gender identity?

3. And finally, what role does group empathy play in the role model effect? Will the desire to engage in politics for young women be higher when exposed to candidates who are from marginalized political groups? In other words, does exposure to any candidate other than the old, white male elicit more interest in future political engagement among Gen Z women who also highly identify with their gender? Are outcomes different for Gen Z men who identify strongly with their gender?

In answering these questions, we consider three competing hypotheses. First, the role model effect could work directly by influencing all Gen Z women to engage in the political system when individuals who represent them descriptively seek public office. It may also work directly by encouraging all young people to participate at higher rates when younger people appear on the ballot. Because factors such as partisanship, ideology, and socioeconomic status play an overwhelming role in determining political activism, however, such effects are likely modest.

Second, social identity theory suggests that the role model effect may be limited to only those women who identify strongly with their gender and use it to inform their political decisions. And third, group empathy theory leads us to explore the possibility that that Gen Z women who score high in gender identity will be more motivated to become engaged in politics when they see young people, women, and people of color running for office, as they represent a coalition of groups who have lacked power historically and for whom there may be a common bond (e.g., Sirin, Valentino, and Villalobos Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2016).

Our study makes several important contributions to the scholarship on representation, role model effects, social identity theory, and group empathy theory. First, there are few studies looking at role models that employ experimental designs. Therefore, our study is uniquely situated to help scholars better understand how gender identity is a driver of future participation in politics. Furthermore, this study represents the first attempt by scholars to understand how a new, more diverse generation of Americans will react to a slate of politicians that are similarly younger and more diverse. Finally, our study is the first to apply group empathy theory to the study of the role model effect. This approach recognizes that Gen Z has come of age at a time when multiple historically marginalized groups have become political allies on the national stage, such that women may see their political fortunes improve with the increased representation of racial and ethnic minorities.

DATA AND METHODS

In order to examine the political preferences of America's youngest voters and how they interact with a slate of candidates that is younger, more female, and more diverse, we turn to a survey of Gen Z Americans. Specifically, we assess whether seeing that young women and people of color are running for public office leads to higher levels of political engagement among Gen Z citizens. Using the survey firm Qualtrics, we administered a survey from July 25 to 31, 2019, on 2,210 adults born between 1997 and 2001. Qualtrics maintains a panel of respondents, which it recruits through a variety of websites using incentives. Participation in the panel is voluntary, though we designed the sample to be representative of the adult Gen Z population in the United States based on gender, race, and region.

Respondents answered a number of questions on demographics and political preferences before being assigned to one of eight conditions. Among these questions, we included two intended to measure gender social identity as a way to determine whether our experimental treatment would affect those for whom gender identity is particularly salient.Footnote 5 The first asked respondents, “How important is being a man/woman to you?” while the second asked, “When talking about men/women, how often do you use ‘we’ instead of ‘they’?” These questions are commonly used in studies measuring affective attachment to salient social identities (see, e.g., Huddy and Khatib Reference Huddy and Khatib2007; Huddy, Mason, and Aarøe Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015). These questions were averaged to form a measure of gender social identity, which we used as a moderator for the treatment effects. We normalized this measure from 0 to 1, though for ease of interpretation we categorized those who scored at 0.75 or higher as “high identifiers” and those scoring below as “low identifiers.”Footnote 6

The treatments came in the form of a fictionalized news story that provided background information on a candidate running for a seat in the state legislature. To assess the possibility of a role model effect, we employed a 2 x 2 x 2 experimental design that varied each treatment in terms of the characteristics of the candidate being discussed and pictured. We randomized the age of the politician (22 or 68), the race of the politician (white or black), and the gender of the politician (man or woman).Footnote 7 The full manipulations with text and pictures can be found in the appendix in the supplementary material online. In all eight conditions, respondents read the following text:

[MICHAEL/MEGAN] Williams announced [HIS/HER] candidacy as a Democrat for the state legislature Friday. A recent [COLLEGE GRADUATE/RETIREE] and [22/68] years old, Williams decided to run for office after successfully organizing a voter registration drive in [HIS/HER] community. After years of low voter engagement in [HIS/HER] town, [HIS/HER] efforts were widely credited for the surge of voting that helped make up the gap in turnout with other parts of the state. Williams told reporters, “I knew that if I did that as a citizen of my town, what could I do as a state rep?”

Because some respondents will infer the partisanship of a politician based on age, race, or gender, we explicitly labeled the politician as a Democrat. The remaining text in the story was intended to show that the politician is engaged and hopeful about the future of politics, but not controversial in any meaningful way, which is why we decided to provide his or her backstory as one in which the candidate had been successful in promoting a voter registration drive and had then decided to run for state legislature. Another important strand of research notes that partisanship can be an important mediator in the role model effect. These studies suggest that role model effects are greatest when there is partisan alignment. That is, a candidacy like Hillary Clinton's likely motivated Democratic women to get involved in politics while doing little for Republican women (Mariani, Marshall, and Mathews-Schultz Reference Mariani, Marshall and Lanethea Mathews-Schultz2015; Reingold and Harrell Reference Reingold and Harrell2010; Stokes-Brown and Dolan Reference Stokes-Brown and Dolan2010). These studies employ observational designs, whereby partisanship often overwhelms other factors that go into the decision to engage or not. For the purposes of our study, we employ an experimental design using candidates with whom the voting public would not have any familiarity to determine if a more diverse slate of down-ballot candidates can generate greater interest in politics among younger men and women.

After the treatments, respondents were asked a number of questions about their political preferences and activities. Included in this was a series of questions designed to measure a respondent's future willingness to engage in politics.Footnote 8 These questions constitute the primary dependent variable of interest. From these items, we developed a composite score that represents a respondent's overall future willingness to engage in politics. Specifically, this battery of questions included eight items in which respondents rated their likelihood of engaging in a number of activities (see Table 1).Footnote 9 For each measure used here, we normalize responses such that 0 is the lowest value for any response (“not at all likely”) and 1 is the highest value (“very likely”). We then take the mean of all eight items to create a composite measure of future political engagement.Footnote 10

Table 1. Summary of future political engagement measures

Note: Questions were asked on a 1–4 scale and recoded 0–1.

Differences between groups can be interpreted as the percentage change across the response scale. Because of the successful random assignment to the conditions, the differences we find in the next section can be attributed to the manipulations and not to other potential confounding factors (Kinder and Palfrey Reference Kinder and Palfrey1993).

RESULTS

We are interested in whether Gen Z women are motivated to engage when they are presented with a politician with whom they share an identity. We consider this in a number of ways. First, do Gen Z women respond when the candidate they are evaluating is nearer to them in age? We answer this by comparing those conditions in which a 22-year-old is named as opposed to a 68-year-old. Second, do Gen Z women respond when the candidate they are evaluating shares their gender? We answer this by comparing those conditions in which a woman is running compared to a man. Finally, we consider matters of intersectionality and group empathy. We ask whether Gen Z women require an overlap of both age and gender to respond, and conversely, we consider the possibility that they will respond positively to all of the candidates who are not older white men.

To answer these questions, we first present the differences between the conditions on future political engagement regardless of gender or strength of gender identity. We also present the results using the white/male/68-year-old condition as the baseline. Again, we do this because this description of a politician fits most closely with the average visible politician in the United States. For example, despite the fact that the 116th Congress was the most diverse in American history at the time of our study, it remained 78% white, 76% men, with a median age of 58. The effects shown in the figures here, then, represent the changes in future predicted behavior when the politician portrayed in the news story departs in some way from the most common American politician.

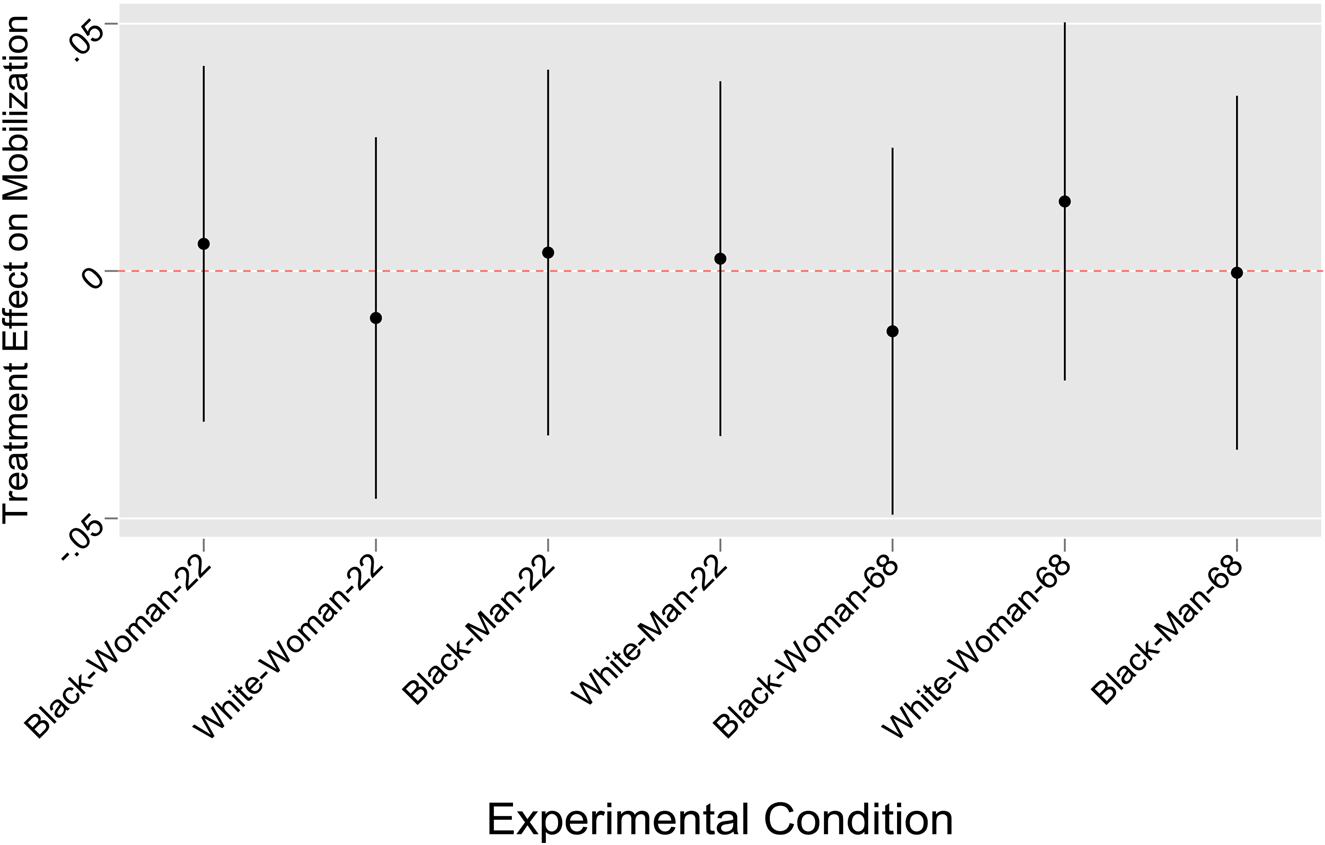

We find no evidence of a role model effect among all members of Gen Z (Figure 1). Because the dependent variable is coded from 0 to 1, these results show that no treatment generated more than a 2 percentage point shift on mobilization and none is statistically significant. Moreover, none of the conditions are significantly different from one another, and it does not appear that the four conditions featuring a 22-year-old performed any better on average than the four conditions featuring a 68-year-old. Taken together these results suggest that, overall, we should expect to see little effect from a more diverse array of politicians running for office on political mobilization among members of Gen Z.

Figure 1. Effect of treatment on mobilization (white/male/68 as baseline). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Although there is little evidence of a role model effect based purely on age, we also consider the potential for salient gender identity to play a role in how members of Gen Z react to politicians of differing demographic characteristics. It is possible that Gen Z women are motivated by seeing more women and people of color running for office in the United States, as they represent a coalition of historically marginalized groups for whom there should be a common bond (e.g., Sirin, Valentino, and Villalobos Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2016). We theorize that this should be the case, and it should especially be true for those who are higher in gender identity or view the political world through a gendered lens.

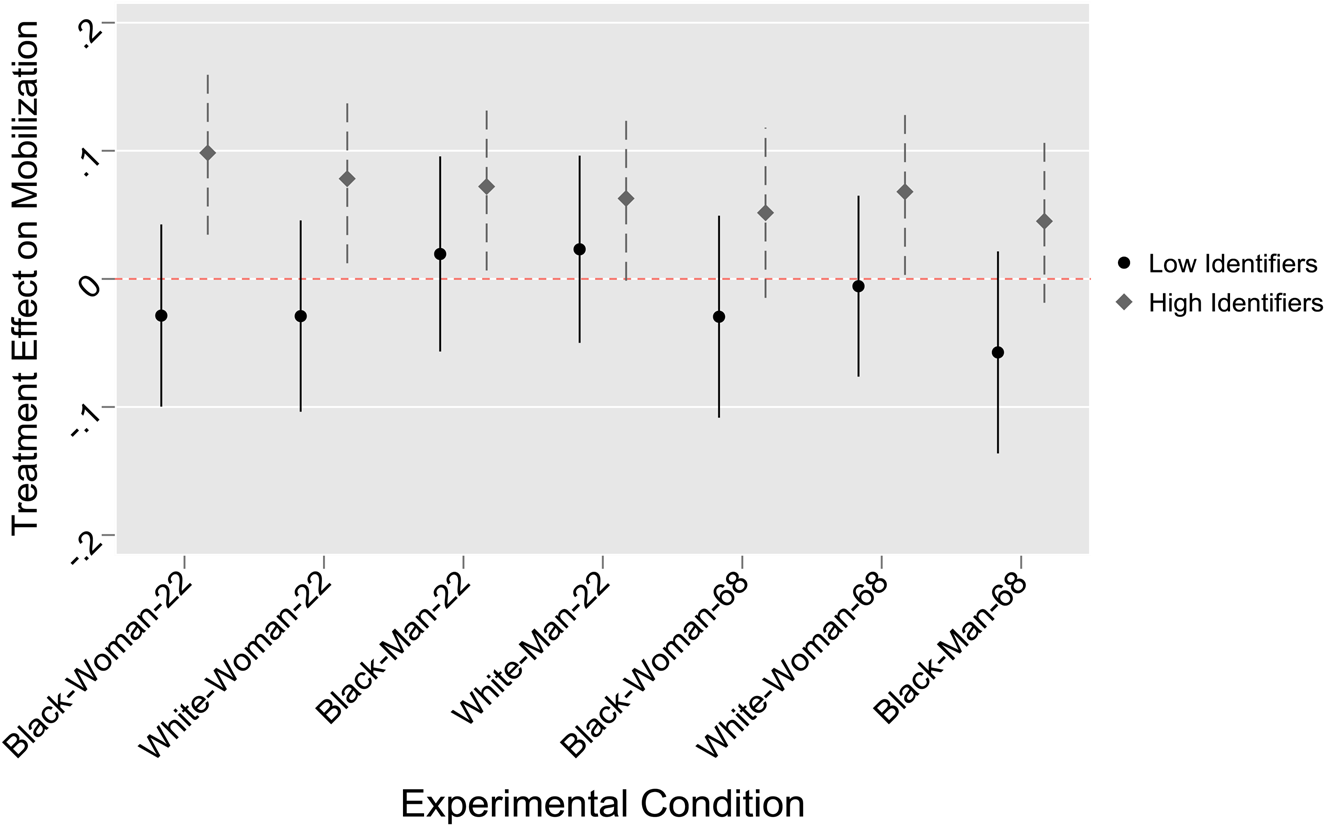

The results in Figures 2 and 3 generally support these expectations. Gen Z men, by and large, do not feel more or less motivated to engage in the political system under any of the conditions. If anything, there is suggestive evidence that seeing minority or female candidates depresses their motivation for getting involved, but these effects are small and statistically insignificant. Furthermore, gender identity among men appears to play little role in determining whether they are motivated to engage in future political activity.

Figure 2. Effect of treatment among men by gender identity. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3. Effect of treatment among women by gender identity. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

The results for women show a more pronounced relationship between the interaction of gender identity and a peculiar type of “role model” effect. Among women low in gender identity, the type of candidate makes no difference to their willingness to engage. Those women who do not feel strongly attached to the gender label experience, on average, a slight decrease in political engagement when exposed to a politician who does not fit the classic description of a politician, though these decreases are small and statistically insignificant. Yet among women high in gender identity, the candidate matters a great deal in terms of future participation. Women high in gender identity are not uniquely motivated to get involved in politics when they see just a female candidate, but instead respond to any candidate who does not fit the privileged stereotype of older, white, and male. While some of the confidence intervals around particular treatment effects are only marginally significant, we see a clear trend toward greater engagement among highly-identified women in all seven of the conditions not featuring an older white male as the politician. The results in Table 2 show that the interaction of the white/male/68 treatment with gender identity is a significant predictor of whether women high in gender identity will be willing to engage in future political activity.

Table 2. OLS regression coefficients: Treatment and gender identity on future political activity

+ p < .1; * p < .05; ** p < .01, two-tailed test.

Taken together, these results suggest that a more diverse slate of candidates for office will motivate young, strongly identified women to engage in the political system without demotivating men or women less strongly identified with their gender. This, in part, may explain why the 2018 election, in which the candidates were historically diverse, saw smaller gaps in turnout between younger and older Americans (Cilluffo and Fry Reference Cilluffo and Fry2019).

Some may be concerned that gender identity is simply a proxy for partisanship among women. That is, women who identify more strongly as women are more likely to be Democrats, and therefore they are more motivated to get involved in politics when they see a politician who fits more closely with the Democratic coalition. In our data, however, we find that the gap between Democratic women and Republican women on gender identity is relatively modest (a 64% to 55% difference in terms of high identifiers). Furthermore, the interactive effect among the treatments and gender identity on future political activity is somewhat stronger among high-identifying GOP women than Democratic women, most likely because the politicians that the Democratic women are evaluating are all Democrats and they are therefore more politically engaged across all conditions. The effect of gender identity is most pronounced among Republican women who lack a similar partisan connection with the politician; among low-identifying Republican women, there is no effect of the treatment on future willingness to engage in politics. Yet high-identifying Republican women are significantly more likely to get involved politically when the politicians they see are younger, women, or people of color—even if those politicians are Democrats. Taken together, then, we believe it is unlikely that gender identity is simply proxying for partisanship.Footnote 11 (Full results of analyses controlling for and modeling the effect of partisanship can be found in Tables A3–A6 of the appendix.)

DISCUSSION

As headlines increasingly suggest that young women are poised to become more prevalent as political leaders in the future, our experimental research suggests one reason why that may be the case: exposure to political figures who defy the traditional white male stereotype appears to raise interest in political participation among Gen Z women. However, exposure to nonstereotypical candidates does not appear to affect all women equally. Our study shows that women who express a strong sense of belonging with those of the same gender are more likely to express intentions to engage in politics in the future. Although women and minority candidates are still far from achieving political parity in elected office, in the past several years, women in particular, including women of color, have made large gains in terms of running as candidates and winning seats to elected office. Many women in Generation Z have witnessed these historic triumphs and are being politically socialized at a time when gender politics is especially salient. Many are coming of age politically at a time when women of all ages—and their male supporters—turned out for one of the largest protest marches in American history to fight for women's equality; the salience of the #MeToo movement, launched less than a year after the first historic Women's March in 2017, also continues to resonate with many Americans, particularly women. Gen Z women were also witnesses to a president who regularly used misogynistic language and often singled out women of color with particularly hateful rhetoric on Twitter and at his campaign rallies (Chittal Reference Chittal2019). These contextual factors might help explain why our experimental treatments had such significant effects on Gen Z women who strongly identify with their gender.

At the same time, exposure to different types of hypothetical candidates based on age, sex, and race had a less significant impact on Generation Z men. Some studies that consider the minority empowerment effect—that is, the impact of seeing racial minorities run for and serve political office upon racial minorities themselves—find that there is a negative impact in terms of political engagement for non-minority voters (Barreto, Segura, and Woods Reference Barreto, Segura and Woods2004; Gay Reference Gay2001). Our research, however, finds only muted evidence of such a demobilizing effect for Generation Z men when they are exposed to nonstereotypical candidates. Why Gen Z men appear to be less interested in future political engagement compared with their female counterparts needs fuller examination in future research, but their lack of engagement is not likely rooted in seeing political candidates who do not resemble them.

Of course, our findings may not apply in situations in which young people are more motivated to become politically active writ large. We attempted a partial replication study of our experiment in late May 2020 using the same online methodology (though excluding the four conditions involving a Gen Z candidate). We suspect base rates of political engagement may have already been high because of the nature of election year politics and widespread frustration over the poor government response to COVID-19, yet this was further compounded by civil unrest throughout the country. During the survey administration, protests began over the murder of George Floyd, driven largely by Gen Z involvement. Because we found abnormally high levels of political engagement during the survey administration, the role model effect was considerably smaller, with some findings consistent with the hypothesis that the race of the candidate, not the gender of the candidate, motivated young men in our sample. These findings suggest that gendered role model effects may be more likely present when current political engagement is not near its ceiling, and when issues of women's rights are more salient in political discourse (results can be found in the appendix).

Nonetheless, our work here is evidence that group identities—in this case, a strong attachment to one's gender—can have a profound impact on political engagement, at least when it comes to young American women. Whether this effect uniquely impacts younger Americans compared with older generations, however, is a question that needs further research. Additionally, whether the incorporation of a more diverse set of candidates for office will help level the historic imbalance of young people's political engagement compared with older Americans, especially in terms of voter turnout (Wattenberg Reference Wattenberg2015), also remains to be seen. As a start, the emergence of newer, younger, more diverse candidates appears to be driving strong interest in politics among Gen Z women who strongly identify as women. This finding holds even among young Republican women, who affiliate with a party that often eschews the importance of diversity among its ranks and is complementary to recent research that suggests that exposure to Democratic women candidates in 2018 also boosted political trust among Republican teenage girls—though at lower levels than their Democratic counterparts (Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Wolbrecht and Campbell2019). Our work suggests that political parties should place greater emphasis on recruiting candidates less representative of the status quo if they hope to attain the support of Gen Z Americans, who are far more diverse than previous generations.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X21000477